An Inevitable Division: The Politics and Consequences of the Labour Split

It’s the changing nature of class and capital that’s caused this split – and should shape the Left’s response to it. But discussing class meaningfully is the last media taboo.

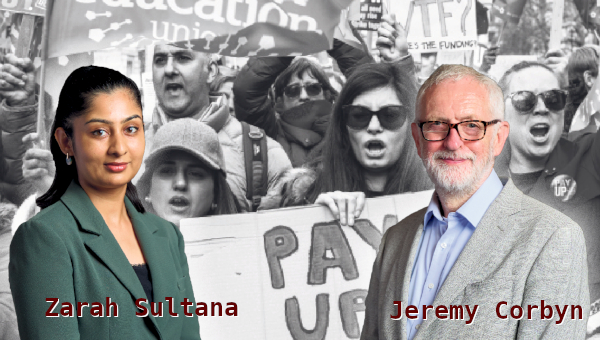

This week’s split of several MPs from the Parliamentary Labour Party (PLP) comes as no surprise at all. It’s been clear since the moment of Jeremy Corbyn’s election as leader that a section of the most right-wing and/or most ambitious MPs would simply never be able to reconcile themselves either to his leadership or to a Labour Party composed mainly of his supporters. This is probably a large section: about a third of the current PLP would be a reasonable estimate.

This isn’t just because of the political differences between them. It definitely isn’t because Corbyn is an anti-semite, or indifferent to antisemitism. It has absolutely nothing to do with the content of the leadership’s stance on Brexit. It has everything to do with the fact that that stance has not been dictated by the City of London and the CBI (Confederation of British Industry).

The Politics of the Labour Right

It’s interesting to try to parse the precise political affiliates and character of the eight. The collection of MPs who have left might seem to come from notionally different strands of the Labour Right. Although he has flirted with a Blue Labour, anti-immigration position (as he has with many others), Chuka Umunna has had most success at convincing Blairite true believers that he is their natural leader: cosmopolitan, pro-business and rich. Mike Gapes, by contrast, belongs to that strand of the traditional, Gaitskellite Labour right that has never really got over its disappointment at the end of the cold war, and tries to compensate by hating pro-Palestinian campaigners and millennial Corbynites as much as they once hated the USSR. But they both nominated Blairite candidate Liz Kendall for the leadership: as did all of the eight apart from Luciana Berger and Chris Leslie.

In fact what seems apparent is that the notional difference between an ‘old right’ tradition represented by the Labour First organization and the Blairite faction represented by Progress has now almost entirely broken down. Since the moment of Corbyn’s leadership election the two networks have been acting entirely in concert in their efforts to prevent Momentum from gaining influence in constituency parties and to undermine Corbyn and his supporters at every available opportunity. There is no longer any clear or stable ideological difference between them, and it seems evident that the clearest way of understanding their position is in basic Marxist terms. They are the section of the party that is ultimately allied to the interests of capital. Some may advocate for social reform and for some measure of redistribution, some may dislike the nationalism and endemic snobbery of the Tories more than others; but they will all ruthlessly oppose any attempt to limit or oppose the power of capital and those who hold it.

One reason for the erasure of difference between them is the changing composition of the British capitalist class itself. Going back to the 1940s, the old Labour Right was traditionally allied to industrial capital: manufacturers and the extraction industries. The Blairites have always been allied to the City and the Soho-based PR industry. But the long decline of British manufacturing, and the financialization of the whole economy, has left a situation in which industrial capital is now an almost negligible fraction of that class. Today, in the UK, all capital is finance capital. So on the Labour Right, they’re all Blairites nowadays. A very similar process can be observed taking place in the centrist mainstream of U.S. politics right now, as anti-Trump neocon Republicans and Clintonite, Third Way Democrats increasingly converge upon a common political agenda (this observation was made very persuasively by Lyle Jeremy Rubin on the latest episode of the Chapo Trap House podcast).

Whatever their political lineage, most MPs and their supporters on the Labour Right are therefore not just reluctant to engage in any radical project of social transformation. They are deeply and implacably opposed to any such project. This isn’t to say that they are bad people. It’s a perfectly reasonable position for anyone to take, in the Britain of 2019, that there is simply no point making vain efforts to limit or oppose the awesome power of the City and the institutions that it represents. In the era of globalization, of China’s rise and the Trump presidency, anyone could conclude that it can only be counterproductive to try to work against it. Many of us take a different view, believing that without severely limiting the power of capital, and soon, the planet itself is probably doomed. But a difference of view is what it is. It shouldn’t lead to moral condemnation.

Appalled and Disgusted?

A good example of the latter is the model motion circulated earlier this week by the Campaign for Labour Party Democracy (CLPD, a long-standing, small, Bennite factional organization) for their supporters to take to their local party meetings. The motion begins with the line “This Constituency Labour Party is appalled and disgusted that seven MPs elected by Labour voters have rejected our party and crossed the floor to assist our opponents.”

I regard myself as sharing almost all of the politics, objectives and analysis of CLPD. But this is unhelpful. Apart from anything else, it is disingenuous. We all know that the Blairites simply have a completely different conception of politics, of the useful function of the Labour Party, and of the kind of role they want to play, than do we on the Labour Left. No supporter of Corbyn or CLPD wants to have these people representing us in parliament. To claim that we are disgusted is to imply that somehow, we naively imagined that we were all on the same side. This is, at best, to admit to profound naivety and stupidity. At worst, it is simply dishonest. Why pretend? Why not just accept, calmly and clearly, that these perspectives simply cannot be contained within the same party, and wish the splitters all the best in pursuing their own agendas?

By all means, we should be pointing out that the splitters, and the allies who have just joined them from the Tory Party, are clearly servants of a very particular set of class interests and a very narrow conception of what progressive politics looks like in the 21st century. But the language of outrage only makes us look like we don’t understand the situation.

As I’ve pointed out before most of the Blairite MPs became Labour MPs on the basis of a particular implicit understanding of what that role entailed. According to this understanding, the purpose of a Labour MP is to try to persuade the richest and most powerful individuals, groups and institutions to make minor concessions to the interests of the disadvantaged, while persuading the latter to accept that these minor concessions are the best that they can hope for. That job description might well entail some occasional grandstanding when corporate institutions are engaged in particularly egregious forms of behaviour (such as making loans to very poor people at clearly exorbitant rates), or when the political right is engaged in explicit displays of racism or misogyny. But it doesn’t entail any actual attempt to change the underlying distributions of power in British society; and in fact it does necessarily, and structurally, entail extreme hostility towards anybody who proposes to do that.

It is crucial to understand that what I’m describing here is not a moral or ethical disposition. It doesn’t make you a bad person to have taken up the role I’ve just described. It’s the simple logic of having a particular place in a system of social relationships, and being allied to a particular set of interests within it.

The Crisis of the Political Class

In wider British society, the immediate political base for the centrist MPs is obviously wider than City millionaires; though not much wider. It is in fact very narrowly rooted in the managerial class: very senior managers in the public and voluntary sectors, a larger section of affluent, property-owning salaried employees in the private sector. Any anthropological investigation of a local Labour Party branch is likely to confirm this claim: it is precisely the people from this narrow demographic who are still the most enthusiastic about Blair, or Umunna, and the most vitriolic in their detestation of Corbynism. Of course there are many exceptions to this characterization (there always are), but the general tendency is clear and unsurprising. The narrow professional political elite of journalists, lobbyists and politicians is, in a certain sense, the leading cadre of this wider managerial class; so it is natural that the latter look up to the former.

Again: there’s nothing wrong or morally reprehensible about this. There’s nothing wrong with being a senior manager, with a vague commitment to an ideal of social mobility and a dislike of the Tories’ explicitly reactionary politics, who really admires Chuka Umunna. There’s nothing wrong with being that, and with violently disliking the people to your left, who probably wouldn’t do that much to limit your own wealth and immediate institutional power if they got into office, but who wouldn’t let you or people like you or the people you most admire run the country to quite the extent that you are used to.

The problem is that in British public life (well, English public life in particular), there is a strong prohibition on ever acknowledging that there are such things as class differences and class interests. And no social group dislikes thinking in such terms more intensely than the professional and managerial classes (and this includes most journalists and political pundits). It is absolutely central to their specific view of the world that such vulgar realities never be acknowledged or discussed, and to assume that only Communists or violent right-wing populists could possibly want to break this liberal taboo.

This is arguably quite different from the perspectives of actual full-blooded capitalists for example: who, when pressed, will often admit that their only aim in life is to make money and keep it, and that they really don’t give much of a damn about ideology, or about the question of who gets hurt. The political elite, along with its most enthusiastic followers in the managerial class, cannot make any such admission to others or to themselves, partly because their whole job is to come up with clever stories about the world and to mediate between the interests of different social groups. If they can’t present themselves as neutral, honest, professionals just trying to make the world a better place, then just what good are they for anything? (This is why the fantasy narratives of Aaron Sorkin, creator of The West Wing, are such a key element of their culture: Sorkinism presents a universe in which political wonks, journalists and tv personnel are all just honest, hard-working professionals doing their best to make the world a better place, and doing a damned good job of it. Again, see Chapo Trap House’s several dedicated episodes for the best critique available of this phenomenon.)

This is also the political elite who cannot acknowledge even to themselves that what is motivating their politics right now is a defence of a set of elite privileges. Which is why they need a narrative like the one about ‘Labour antisemitism’ in order to justify their actions to themselves and others. It would be very difficult indeed for any objective observer to concur with Joan Ryan’s claim today that Tony Blair and all previous Labour leaders unstintingly “[stood] up to racism in all its forms,” and that antisemitism “simply did not exist in the party before [Corbyn’s] election as leader” (as Ryan should presumably know if she’s actually spoken to Luciana Berger). It would be clear to an objective observer that the right has been using the claims that Labour is “institutionally anti-semitic,” and blind and inactive where issues do arise, in a cynical and shameless fashion to try to justify their implacable hostility to Corbyn.

For months, campaigners on the Right insisted that the only way Corbyn could demonstrate his commitment to fighting antisemitism was by accepting the IHRA definition of anti-Semitism in full, despite the fact that even the original author of that definition had publicly disowned it as not fit for purpose, and Labour’s modification of it was a clear legal improvement. No sooner had the Labour NEC finally accepted the definition, then campaigners switched to claims that ‘complaints of antisemitism were not being properly investigated’, despite the evidence that complaints were now being investigated considerably more thoroughly than they were whilst the Right, under McNicol, retained control of the party bureaucracy.

So it is important to understand why a certain section of the public are so willing to believe this narrative. The reason is that they are members of a particular social group that crystallized and came to prominence in the 1980s and 1990s, as the traditional professional classes declined (having been subsumed into the public sector during the post-war years, then battered into resentful compliance along with the rest of that sector by Thatcher and her successors). It is this group – the professional political elite and their most loyal followers amongst the wider managerial class – that is now suffering a traumatic and disorienting existential crisis.

Neither the professional elite nor the managerial class ever enjoyed much authentic legitimacy amongst the wider public. The broader public deferred to their new bosses for as long as they got the compensations offered by an ever-expanding consumer culture, enabled by cheap credit and Chinese imports. Since 2008, fewer and fewer members of that wider public have been offered the same compensations, and so the authority and legitimacy of the political / managerial class has been in terminal decline. Both Corbynism and the Brexit vote are symptoms and examples of the public finally refusing their authority.

That is why Brexit represents such a traumatic existential crisis for these elites, and why they cannot separate it from Corbynism in their collective imagination. It is clearly absurd, in objective historical terms, to blame Corbyn for Brexit, or to keep demanding that he ‘come out’ against it when his doing so would make no difference at all to the parliamentary reality (there is no majority in the house of commons for a people’s vote). But the members of this declining, delegitimated social elite have experienced both Brexit and Corbynism as part of exactly the same process; the process by which the people that they have governed and managed for a generation have turned around and rejected their authority and their world-view. Embracing the idea that Labour is institutionally antisemitic and racist, and that Brexit is Corbyn’s fault, are understandable psychosocial responses to the experience of this historical trauma. (And again, Chapo Trap House’s excellent recent analysis of the way in which claims of antisemitism have been mobilized against the Left in the U.S. is pertinent). Such a response allows the members and partisans of this elite to tell themselves that they are defenders of liberal values, so that they do not have to face up to the fact that, in opposing Corbyn, they are defending nothing but their own sectional privileges and those of their corporate liege lords. What these stories are not is rational, descriptive accounts of any kind of objective social reality, that can be reasoned with politically or morally.

What Do We Do?

For the Labour left, the political conclusions to be drawn from this analysis are stark, but important. As I’ve already suggested – we should not be responding to the behaviour of the centrists with simple moral indignation. Their entire project is to wrap up their defence of their own elite interests in a language of moral indignation – accusing the Left of racism, of being responsible for Brexit, of ‘bullying’ (ie expecting elected representatives to be accountable to members and constituents). But the more that we respond to them with our own language of outrage and betrayal, the more that we legitimize these fairy-tales, rather than exposing them for what they are.

By the same token, it is crucial not to fall into the sentimental trap of imagining that if only we are nice enough to them, then we will be able to prevent the Right from doing everything in their power to prevent the success of Corbynism. The split was always going to happen, and the only thing we could truly do to stop it would be to let the neoliberal centrists have control of the party once again. Tom Watson’s recent interventions make this very clear. He calls movingly for a kinder and gentler approach to politics, expressing moral outrage over the horror of antisemitism. But what he wants is a shadow cabinet reshuffle to represent ‘the balance of opinion in the Parliamentary Labour Party’. Presumably he doesn’t want one that would actually represent the politics and views of the current membership: if it did, then it probably wouldn’t include Tom Watson.

Either we’re going to give them what they want – full control of the party once again – or we’re not. And if we’re not, then they will do everything in their power to damage our cause. Because there can be no real doubt that this is the aim of the split, and that the long-term split is planned to come in waves rather than all at once, and this has been planned not because it is the most effective way to launch a new party, but because it will maximize the long-term damage to Corbyn’s Labour.

This is a surprisingly unpopular view amongst mainstream Corbynites. The caricature of Corbynites is that they are all wild-eyed sectarians, hell-bent on deselecting every MP to the right of Chris Williamson. This isn’t true at all. Frankly, I think it isn’t true because many Corbyn supporters are actually rather naive about the political character of the Labour Right. They, like Corbyn himself, do not actually see the world in terms of Marxist (or Gramscian) political sociology; rather they see it in moral terms, as a conflict between decency and justice on the one hand, greed and militarism on the other. They know that the majority of even the most right-wing Labour MPs are not Bad People, and so they assume that sooner or later they will come round to supporting Corbyn, if only he shows willingness to address their legitimate concerns on Brexit and antisemitism.

This is just a categorical analytical mistake. Corbyn could convert to Judaism, apply for Israeli citizenship and call for a People’s Vote tomorrow: their attacks on him would not relent for one second unless he agreed to give up control of the party; or at least to commit to a policy agenda approved by Merrill Lynch.

The view that there is no point trying to prevent the right from splitting is also unpopular because, for all of its radicalism and democratic potential, mainstream Corbynism remains a left-wing version of Labourism. Labourism is the ideology that assumes that the Labour Party and only the Labour Party must be the vehicle to bring socialism to the UK, and that the only route to that objective must lie through the securing of a parliamentary majority for Labour in the House of Commons. The problem now is that if there is a significant split in the party, then it will put Labour back in the position it seemed to be before the 2017 election: unable to realistically aspire to a parliamentary majority of its own, forced to face (if not to answer) uncomfortable questions about its possible future relationships with the Scottish National Party (SNP), the Greens, even the Liberal Democrats, in a complex ecology of parties, factions and tendencies. The Labourist imaginary abhors this vision. It wants to live in a world in which the Labour Party, alone, united under a relatively progressive leadership, can win a large parliamentary majority against a once clearly-defined opponent (the Tories), and implement a progressive programme. It wants, very very much, to live in 1945.

The trouble is we don’t. We don’t live in 1945, and the ideological differences between the Blairites and the Corbynites are of a different existential order to the ones between Bevanites and Bevinites in the 1940s. They may have hated each other, they may have had entirely different attitudes to both capitalism and communism. But they didn’t represent social constituencies whose interests simply could not be reconciled even in the short term. The miners, the skilled engineers and even the manufacturers all stood to make immediate gains from the success of Labour’s programme, as did all their leaders.

This is unlike the current situation in some key ways, although it is similar to it in others. Many of the managerial class in fact have a great deal to gain from a Corbyn victory, because their own children are suffering so badly from labour-market precarity and unaffordable housing (and this, as much as Brexit, is why so many of them voted Labour in 2017). But if they are going to achieve those gains, then they will have to make some significant concessions to groups lower down the social hierarchy. In the public sector, for example, senior managers may well have to accept some relative reduction in their salaries and some increase in the autonomy of those they manage. This potential loss puts them in an ambivalent position, potentially supportive of Corbyn’s agenda, but anxious about what it might cost them. But their symbolic leaders in the media and full-time political elite have absolutely nothing to gain, and can only lose, from the success of Corbynism. For this reason, they simply will not stop trying to do everything in their power to drive a wedge between their followers and the rest of the Labour Party. There’s no point pretending that they might.

At the same time, there is no point pretending that in the volatile world of 21st century politics, the political divide between those inside the party and outside of it is the most important one that matters. There are members of every other party – even the Tories – who have more in common with Corbyn’s ideological agenda and more sympathy for his political programme than do those MPs who are reported to be considering joining the split. More importantly, there are members of every other party – even, indeed, the Tories – who are less clearly aligned with class interests that are inimical to Labour’s project.

Political success is always about leading complex coalitions of interests. The Labourist fantasy is that all elements of such a coalition can always be contained inside the Labour Party. As the split deepens, it will become apparent that Labour’s remaining vote and support will not be enough on its own, or even after another period of considerable growth, to win the battles that Labour needs to win.

Coalition of Progressive Forces?

Labour must seek to lead a coalition of progressive forces. All parts of that formula are important. It cannot keep pretending that all sections of the Labour Party are even potentially progressive in character. It cannot afford to ignore the existence of progressive forces outside of Labour or the need to make common cause with them. It must seek to lead that coalition. Nobody is suggesting that it submerge its identity or dilute its programme: that isn’t what leadership means.

But Labour must also be alive to the specific political objective of the ‘Independent Group’. There is a clear international precedent for the path that they are taking, in trying to establish a centrist party that could only ever be small, only ever appeal to the managerial class, and never hope to command a mass base, while pursuing a pure neoliberal agenda. In Germany, the Free Democratic Party conforms to precisely this description, only ever winning around 10% of the vote. From this position, it has held the balance of power in almost every West German and German parliament since 1948.

It’s always been logical that the legatees of the Third Way would eventually opt for this as their ideal political model. Labour, the traditional party of the organized working class, was always a strange and uncomfortable home for them in many ways. The problem for Labour is that if this group manage to establish this position for themselves, then they will pose a permanent obstacle to progressive government unless a very broad-based movement can be built to stop them. In 2016 and 2017 many of us hoped that the dream of Labour becoming a million-member party might be realised. There seems little chance of that now. Ultimately the social and political terrain of 21st century Britain is still too complex and too variegated for any one organization to unite that many people. But we still need a million-member movement, if any chance of real progress is going to come onto the horizon. This is the movement that Labour must seek to lead, and must accept that it can never entirely contain.

If the Labour leadership really wanted to engage with the current situation meaningfully, this is what it would do. It would not retreat into ideological purism. It would not lift another finger to prevent the Blairites from leaving the party. It would convene a national conference, inviting Greens, social democrats, communists, socialists, liberals, Scottish and Welsh nationalists, trade unionists, NGOs and others to discuss the political and social crisis facing the country. The explicit aim of the conference would be to find an inclusive and effective road-map to take the country beyond neoliberalism. Those who share no such commitment need not be included. But everyone who shares it should, including those stalwart social democrats of the old Labour right who retain some authentic commitment to a political objective other than defeating Corbynism. This would be a meaningful way of neutralising the charge that Labour is not a broad church, and would help to isolate those elements who want to claim the mantle of diversity in order to sustain the neoliberal order.

Is this exactly the right solution? I don’t know. Maybe there are many other possible answers. But I know that the question is the right one: how do we assemble all of the potential allies at our disposal, to build an alternative to neoliberal hegemony, without getting bogged down in pointless debates with those who only want to defend it? That’s the question that the party and the leadership must now answer, if the splitters – who want nothing more than to maintain neoliberal hegemony – are not to get their way. •

This article first published on the Open Democracy website.