Ontario Looks Right

While U.S. socialists have always challenged the myth of American exceptionalism – that the U.S. is immune to class struggle and a politics linked to it – they tend to have the opposite view of Canadian politics: that the latter is somehow exceptional, rooted in a classic social-democratic and even socialist political culture that makes it immune to reactionary trends like Trumpism and the right-wing populist wave around the world.

But Canada, and its industrial heartland and largest province of Ontario, is far from immune from these forces. Case in point: the June 7 election of a right-wing populist government of the Progressive Conservative Party of Ontario (PC), led by politician and businessman Doug Ford.

Canada has gone through a number of less reactionary but austerity-driven Conservative governments, most recently that of Stephen Harper from 2006–2015, and Ontario was ruled by a more moderate PC for forty years before hard-line, Thatcher-like neoliberal PC governments ruled from 1995–2003. That draconian regime drove the Ontario economy into the low-wage, low-tax, “anything-goes” development model that dominates today. The Liberal government that succeeded it over the past fifteen years did little to challenge that model.

The election of the PCs in Ontario should have been expected. The PCs were far out in front in the opinion polls for over a year. The party suffered from internecine leadership struggles in the past few months but still maintained a huge lead until the last part of the election campaign. The PC’s popularity was based especially on the anger of people across the province with the long-standing incumbent governing Liberals.

Exhaustion With the Liberals

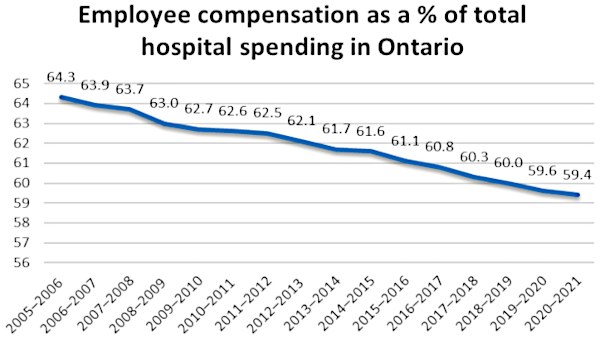

Ontario Liberals fancy themselves as a “centrist,” business-friendly party that seeks to integrate the needs of capital with workers, combining competitiveness-oriented policies with forms of positive social reforms, vacillating over time between the two policy poles. In reality, it has continued the low-wage economic model it inherited from the previous PC government, driving down spending on social programs slowly – ultimately leaving Ontario with the lowest program spending per capita in the country.

Over its mandate, the Liberals accumulated several scandals and policy boondoggles, along with some moderate reforms. By the time this election was called, there was a general weariness and disgust with them that was captured by Ford and his party.

Some of that weariness came from a more traditional conservative aversion to government spending and taxation and being insufficiently business-friendly. Some reflected opposition or uneasiness with the progressive changes to the labour code made by the Liberals in their final months, in response to mass pressure and protests and an eye for capturing progressive voters, including increasing the minimum wage to $14 with plans to move to $15 per hour.

Kathleen Wynne’s government kept a lid on social-service spending, squeezing education and in particular healthcare, then partially reversing itself in the buildup to the election to take votes from the NDP. People objected to the scandals, the selling off of 53 per cent of the Hydro One electrical utility, and the swift move of the latter to pay its now-private executives shockingly high salaries. Those on both the Right and Left opposed the government for different reasons, while drawing opposite conclusions of what to replace it with.

As in all the right-wing populist movements in the Global North, issues such as job insecurity, workplace closures, relatively high personal tax levels (in a province where government spending per capita remains abysmally low), fed fear and anger amongst key sections of the electorate, and the working class in particular. According to figures cited by Peter Graefe of McMaster University, even with relatively low general unemployment levels (5.5 per cent), the lowest in fifteen years, there remains an exceptionally low labour participation rate, as the percentage of Ontarians aged 15–64 participating in the labour market declined from 79 per cent in 2003 to 72.3 per cent in 2017.

A Social-Democratic Opening

Frustration with the government and opposition to the possibility of a right-wing populist PC victory fueled a response on the Left, as well. While the PCs initially led in the opinion polls, their lead was steadily eroded by the social-democratic Ontario New Democratic Party (NDP). The predicted popular vote for the NDP and PC were virtually tied by the week before the election. But the first-past-the-post electoral system favored the PC, and the popular vote was skewed in a way that gave them enough seats to form a comfortable majority.

As such, much of the frustration with the Liberal government was divided between the PCs, who ended up with 40 per cent of the popular vote, translating into seventy-six parliamentary seats and a clear majority (sixty-three needed), and the social-democratic New Democratic Party (NDP), who took 34 per cent of the vote, translating into forty seats. The governing Liberals took 19 per cent of the popular vote, translating into seven seats. (The Greens won one seat with 4.6 per cent of the vote.)

The NDP is a party of moderate social reform, the successor to the more radical Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (CCF), which was founded during the Great Depression and transformed after the 1930s into a moderate Keynesian party. In 1961, a further effort to become more “mainstream,” working with the Canadian Labour Congress (CLC), led to the creation of the NDP.

In its earlier days, the NDP championed some of Canada’s key social-welfare reforms. In the neoliberal period, the party reflected the Third Way orientation of sister parties in the Global North. Its one time in power in Ontario was in 1990–1995. The party’s current leader, Andrea Horwath, ran two previous middle-of-the-road electoral campaigns that proposed very limited reforms, couched in a discourse of financial orthodoxy. They were outflanked on the left by the Liberals in the 2014 election. This time, they had a more ambitious set of moderate social-democratic proposals, including a form of dental care, day care, Pharmacare, transit, measures to facilitate unionization, and a commitment to fighting privatization.

The NDP also fielded several activist- and left-oriented candidates in some ridings. As the campaign progressed and the precipitous drop in Liberal support became apparent, the NDP became the only electoral challenge to the prospects of a Ford victory. Because of this, much of the Left (and Liberals) rallied behind them.

In purely electoral terms, more voters chose moderate or progressive options than those who chose the PCs. The Liberals couched themselves as “responsible” social reformers, opposing both the draconian right-wing platform of the PCs and attacking the NDP for somehow being too negative toward the private sector or even “socialist.” Yet, the Liberal defense of the flurry of reforms they introduced in the waning months of their mandate made them appear to be progressive in some ways.

Looked at this way, the majority of voters actually voted for more progressive policies than Ford’s PCs. It’s hard to portray the electoral outcome as a wholesale endorsement of right-wing populism. Yet Ford has a majority government at his command.

Clearly, the Ontario electorate is divided in this province. Ford got most of his seats from the rural, exurban, and suburban areas, and traditionally conservative spaces. The NDP elected people in larger urban centers and places where organized labour remains strong or has an historical resonance. But even there, the story isn’t that simple; class, demographic, and ideological differences and contradictions helped shape the outcome.

Doug Ford, the PCs, and Right-Wing Populism à la Ontario

Doug Ford is a multimillionaire co-owner of Deco Labels, a labeling and packaging business based in Chicago and Toronto. He and his brothers inherited it from their father, who was a member of the hard-line, neoliberal PC government of Mike Harris. Doug was a city councillor in Toronto, while his infamous brother, the late Rob Ford, was the mayor who was seen on video smoking crack not long before he died in 2016.

Both Ford brothers wore the mantle of “standing up for the little guy,” using the standard right-wing populist arsenal of opposition to taxes and government spending (referring to the “gravy train” of government waste and “privilege”), public housing, and services; opposing above-ground public transit, defending car dominance of the roads and championing privatization.

But populism of the Right has different inflections in different places. Ford is not openly racist, as is President Donald Trump. Ford courted fiscal and social conservatives within different immigrant communities and communities of color and carefully balanced not-so-concealed appeals to racism and xenophobia with base-building across ethnic and other social divides.

In running for the leadership of the PC party – just a few months before the election – Ford brought his persona and politics with him, much of it as simplistic and obnoxious as Trump. He spoke about “The People,” about bringing “relief” to the “hard-pressed” taxpayers of Ontario, “putting more money in your pocket and letting YOU decide how to spend your hard-earned money,” about cutting taxes and making the province open for business investment in order to create jobs.

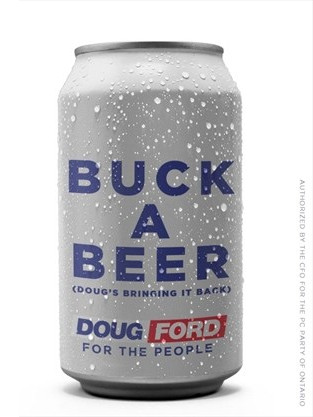

While the party gave no costed platform, explaining what exactly the party’s policy intentions were and how they were going to pay for them (and Ford made sure of keeping the media at arms length throughout the entire campaign), their promises were a mix between usual right-wing populist issues and promises peculiar to the Ontario context: cutting the already low corporate tax rate; scrapping the cap-and-trade agreement with California and New York and opposing any carbon tax; reducing gas taxes by 10 cents per liter (the source of much public-transit funding); cutting income tax by 20 per cent for “middle” and upper level earners; freezing the minimum wage and introducing a low-wage tax credit; introducing a meager increase in healthcare spending for long-term care; scrapping a revised (and socially progressive) sex-education curriculum; bringing in provincial ownership of subways and increasing spending on subways (to the detriment of other forms of mass transit), and promising “a buck a beer.”

While the party gave no costed platform, explaining what exactly the party’s policy intentions were and how they were going to pay for them (and Ford made sure of keeping the media at arms length throughout the entire campaign), their promises were a mix between usual right-wing populist issues and promises peculiar to the Ontario context: cutting the already low corporate tax rate; scrapping the cap-and-trade agreement with California and New York and opposing any carbon tax; reducing gas taxes by 10 cents per liter (the source of much public-transit funding); cutting income tax by 20 per cent for “middle” and upper level earners; freezing the minimum wage and introducing a low-wage tax credit; introducing a meager increase in healthcare spending for long-term care; scrapping a revised (and socially progressive) sex-education curriculum; bringing in provincial ownership of subways and increasing spending on subways (to the detriment of other forms of mass transit), and promising “a buck a beer.”

Instead of renationalizing Hydro One, they promised to fire the company’s high-earning officers and to lower electricity bills. (Previous PC governments began the process of privatizing electricity markets.) And, Ford, unlike his luckless PC predecessor in the 2014 election who boasted of 100,000 public sector layoffs, guaranteed that there would be no job losses as a result of “efficiencies.”

The rough edges of this are clear: severe cuts to state revenues, subsidies for the wealthy, spending promises that can’t be fulfilled without radical cuts to services, an end to environmental initiatives with renewable energy, downward pressure on public sector and other workers’ wages and benefits, and an appeal to social-conservative opposition to updated and progressive sex education in schools. He also opposes safe injection sites for drug users and maintains a “law and order” stance in favor of unfettered police powers.

So, who does he appeal to? Aside from more conservative workers, the wealthier voters favor Ford’s promotion of their interests. Entrepreneurial types who look to replace public-service delivery with low-wage private services see openings.

The business community has supported Ford wholeheartedly. He is committed to further deepening the low-wage model and undoing even moderate reforms introduced by the Liberals. Key members of the business class have grumbled about Canada’s failure to match the Trump tax cuts. Ford offers an unmistakable move in this direction.

On the other hand, key sections of the capitalist class also look to increased investment in infrastructure, transit, and education. It’s unclear how Ford’s promises to dramatically cut revenues would allow the expenditures necessary to make that happen.

The Making of a Right-Wing, Working-Class Voter

There were many working-class Ford supporters, and their support reflects several of the contradictions in working-class life in neoliberal capitalism. In the face of ongoing concerns about job insecurity, stagnant incomes, and deindustrialization, especially in smaller communities, workers are conflicted about how to respond. Unions are limited and weak. Few workers have experience with collective resistance or demanding government limitations on the power of capital.

On the contrary, many blame governments for high taxes and too much “regulation,” for the most part believing that only the private sector can provide “real” jobs and see regulation as an impediment to job creation. Many are so frustrated that they are open to racist, xenophobic, and sexist appeals by the Right. There are no mass political movements or organizations that challenge those beliefs, and right-wing populists like Ford have ready-made – if bogus – responses.

Many workers have difficulties paying their bills and identify taxes as a leading cause of their problems rather than stagnant wages and low-wage jobs. There are also huge imbalances between rural and urban life which shape the way workers in the latter look at the world. Even as the effects of climate change become clearer, reliance on cars in suburban areas increases, keeping many workers sensitive to the cost of gasoline. Carbon taxes and the like are seen as a burden, rather than part of a solution to environmental degradation.

In response to the many challenges of working-class life, people are encouraged to move up the ladder of class and income, seeing successful capitalists as role models to emulate rather than a class which runs and benefits from exploiting them. People living in cities, on the other hand, are portrayed as somehow being part of a despised “elite,” benefiting from new private business and service investments, and somehow enjoying lifestyles denied to people in smaller, rural areas.

Collective resistance and class solidarity don’t automatically occur: they need to be built. In their absence, people are open to the solutions posed by Ford and his allies. But, even with these appeals, half of the electorate responded negatively to Ford’s message.

Still, noticeably weak in the campaign was the labour movement. Three different unions waged competing anti-privatization campaigns in the year leading up to the election and were in no position to wage a sustained anti-Ford campaign with its own agenda. They did little or no education in most unions with their members, let alone in their communities, about the underlying issues, other than official appeals to vote for the NDP. Without any socialist political party or movement with roots in working-class communities or institutions, this is not surprising.

During the final weeks of the campaign, the PCs aired an effective series of ads which targeted the NDP. Attacks on NDP candidates aimed at “radical activists” and “lawbreakers” (who were indeed the more progressive and activist people in the party), went relatively unanswered, as did ads saying that the NDP would chase business out of the province. The NDP had few answers for the latter attacks.

Ford’s brand of right-wing populism fits into the context of Canadian and Ontario political culture, much as Trump has his roots in the peculiarities of U.S. populism. Both are odious. The PCs don’t openly call for privatizing Medicare or education, or even public transit. Public and working-class support for these services play a greater role in the political culture of Ontarians than Americans. But that doesn’t mean that the new government won’t build on people’s frustrations with these public goods and look to undermine their non-commodified elements or undermine public ownership and control over time.

The same is partially true for avoiding the open embrace of nativist, anti-immigrant, xenophobic, racist, and homophobic elements of U.S. right-wing populist culture. They are present in the PC caucus, party, and in Ford’s politics. Social-conservative elements within different Canadian demographic segments including immigrants and native-born whites were clearly courted by Ford, and his bloc of supporters includes large numbers of people with economically and socially conservative ideas from different communities (some of whom are elected MPPs).

Ford mobilized voters over the sex-education issue both outside and within some immigrant communities, but also the planned legalization of marijuana by the Federal Liberal government. The PC’s tapping of social-conservative views within certain communities, in the context of Canada’s multicultural ethos, has the potential to create an identitarian mobilization on the Right, even as it opens space for white supremacist groups.

Along with this were dog-whistle appeals to those open to the worst of these positions, such as when he said that Northern Ontario should provide jobs to all the jobless in the province before inviting immigrant workers to fill openings in these communities. He also reinforced homophobic and misogynistic attitudes toward the current premier, Kathleen Wynne, who is a lesbian (particularly in his opposition to the updated sex-education curriculum which includes thoughtful introductions to LGBTQ issues). His campaign showed a disdain for “political correctness” similar to Trump’s.

Most disturbing is the crew of unsavory hard-right activists who used print and social media to put forward a more unadulterated form of hatred – groups such as Ontario Proud and the Toronto Sun tabloid. The latter developed a campaign against the NDP’s proposals to provide rights and services to immigrants and refugees, claiming that it would waste resources necessary to provide services to “deserving” Ontarians. Ford has refused to dissociate himself from these groups.

As a sidelight, a few days before the election, the widow of Doug’s brother Rob announced a lawsuit, accusing the future premier of cheating her and her family out of Rob’s inheritance and running the family business into the ground. Like the accusations of Trump’s philandering and sexual assaults on women, it had no effect on the election’s outcome.

Resisting Ford and His Agenda

Within progressive spaces, social activist groups, left organizations, trade unions, and communities, there are feverish discussions about how to resist Ford. This will not be easy.

Many are looking at the last time the hard right was elected in this province. In the mid-1990s, after small but determined groups of anti-poverty and community groups organized various protests against the first attacks of the Harris government (a 21 per cent cut in welfare rates and elimination of an anti-scab law), the trade union movement organized.

The Days of Action were a series of one-day, rotating general strikes and mass demonstrations, co-organized by the Ontario Federation of Labour (in the name of a bitterly divided union movement), in partnership with local coalitions of social and community activist movements and groups. Hundreds of thousands of workers struck their employers, joining with community members and marching together in mass rallies.

The key to the success of this tactic were the mass, intensive education campaigns with workers in each city, many of whom had voted for the PC. The education campaigns succeeded in convincing a number of workers not only to change their minds, but to engage in illegal strikes against their employers, forcing the latter to pressure the government to change its policies.

The government was forced to moderate its offensive, though it was ultimately reelected four years later. But the change in attitudes by many workers and the experience of organizing extra-parliamentary struggle marked a major step forward for province’s working class and helped to transform some unions’ culture. That later set the stage for further movements like the anti-globalization mobilizations within unions.

There are several lessons that one can quickly draw from the experience of the Days of Action and the fightback against right-wing populist regimes elsewhere. Clearly, without engaging the working class as a whole, in unions as well as communities, you can’t build a movement that can confront both employers and the government. Simply taking verbal pot shots at the obvious buffoonery of Ford (or Trump for that matter) doesn’t change anything. It simply emboldens their base.

There has be a series of alternative policies and approaches popularized across the working class that can address many of the workers who supported Ford and his party. Mass democratic movements of workers, women, indigenous, LGBTQ people, tenants, and more need to be ready to disrupt the workings of the system that Ford looks to impose. This won’t be easy.

The NDP (like the Democrats in the USA) will include elements that can be part of any resistance movement. Some of the newly elected MPPs have excellent activist histories that have placed them decidedly to the left of the party’s leadership. They should be welcomed as allies.

On the other hand, the NDP has a history of limiting the space for left critiques and activism within its caucus. Leader Horwath has already made moves to limit the party’s role to being an official parliamentary opposition and a government-in-waiting. This doesn’t bode well for the NDP’s potential role in any movement.

But it is critical not to subordinate any movement’s autonomy or leadership to that of a moderate, electoral political party like the NDP. It is important to keep in mind that the latter only became the center of electoral opposition to Ford because of the collapse of the Liberals and the lack of any real left alternative.

Most important is to build what was completely lacking in the last major popular push against the Harris years: socialists have to work with allies to change the opinions and understanding of working people who look to the false solutions of Ford. This can’t be done in isolation, but as part of building an alternative resistance in unions, communities, and other working-class spaces and institutions.

It means combining socialist principles with deeper education about the causes and solutions to challenges posed by neoliberalism, along with learning about right-wing populism and its agenda. Socialists need to argue that a clear analysis of the conjuncture and of the nature of our forces and those on the other side is essential in building solid resistance. This has to be done inside and alongside unions and working-class institutions and spaces and social movements, around all kinds of issues that have a class component: housing, transportation, education, workplace issues, jobs, social programs, racism, sexism, homophobia, and more.

Upcoming municipal elections across Ontario in October provide a potential space to mobilize resistance across the province if the Left can build sectoral networks around the above issues, in alliance with elected officials, candidates, and community and labour activists.

Socialist organizations and individuals are small and isolated. We can’t control the larger course of events, but we can contribute toward building a countermovement against Ford and the broader right-wing populist push he represents – a movement that can ultimately move from playing defense against these forces to offense. •

This article first published on the Jacobin website.