If Housing is a Right We Should Take It

In Toronto and across Canada, homelessness has reached proportions that no rational and just society would tolerate and it constitutes an emergency situation. The Trump Administration, seeing levels of destitution in California that are producing social dislocation, is preparing for a brutal crackdown on the homeless. We would do well to understand how close we are in Toronto to a comparable situation. The political agenda of austerity and social cutbacks is getting worse, the extreme commodification of housing continues to drive up rents and forces people onto the streets and, globally, conditions of economic downturn are unfolding. As more and more people are rendered homeless, the kind of incarceration option that Trump favours will undoubtedly enter into the plans of the more centrist representatives of the neoliberal order.

If we are to avoid, in the next period, a dramatic intensification of homelessness, a public health tragedy and the adoption of draconian measures against those thrown onto the streets, it is obvious that significant action must be forced out of governments at every level. Wages and social benefits must be raised to levels that enable people to meet the costs of rent and, in place of the farce of ‘affordable housing’ the poor can’t afford, social housing must be built on a scale that meets the need that exists.

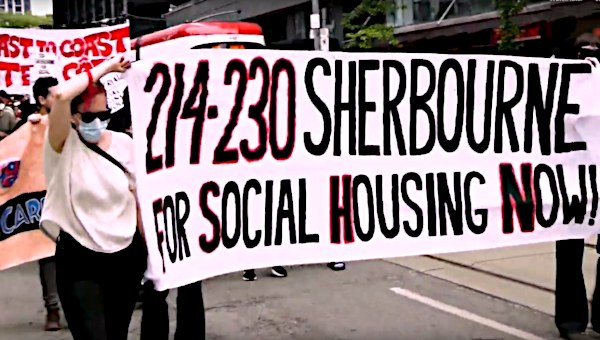

At present, some important struggles are underway to win concrete gains in the provision of housing. The Ontario Coalition Against Poverty (OCAP) is campaigning for the creation of social housing at a location in Toronto’s Downtown East. In the face of determined and sustained community pressure, Vancouver City Council has voted to expropriate two badly neglected hotels in order to create viable housing in the Downtown Eastside. As significant as initiatives like this are, it is clear that we need to move on a much wider front and win much more substantial gains, if we are to seriously address the mounting crisis.

The Housing is There

Within an enormously wealthy G7 country like Canada, it is obvious that large scale and growing homelessness reflects, not a lack of resources, but a set of societal priorities and political choices. The UN Special Rapporteur on adequate housing, Leilani Farha, has called for an emphasis on housing as a human right, rather than as a commodity. If we think in those terms, we must certainly challenge the oversupply of upscale housing that a developer led approach leads to. However, even with the distorted priorities that have governed the creation of the present housing stock, there are ways to we could act to meet the needs of those who are homeless and the many more who are precariously perched on the edge of destitution.

The Daily Hive suggested last August that there are 66,000 empty homes in Toronto, with housing speculation as a major cause of this. This estimate actually includes short term rentals but, if even a quarter of this figure represented empty properties that could provide housing, we are looking at a shameful misuse of a vital social resource. The City of Toronto’s latest figures on the homeless shelter system, gathered on December 30, show 7,301 people in the official shelters and another 704 in the substandard back up system. There were homes for all them to sleep in that night but they sat empty.

When it comes, specifically, to the condos in Toronto, there is further strong evidence that people sleep on the streets and, sometimes, die on them, while perfectly decent housing sits vacant. Jaco Joubert, a designer who is concerned about the issue of housing inequality, set up an elaborate system of photographing condos. He took regular photos of fifteen buildings throughout the night for a week and, then, repeated this several months later. With this methodology, he obtained a plausible estimate of the number of units that were unlit and unoccupied. He calculated that, on average, the buildings had 5.6% of their units standing empty. Between 2008 and 2018 alone, 206,392 condo units started construction in Toronto. If 5.6% of those were sitting empty there would be 11,557 vacant homes that could easily house Toronto’s shelter population twice over. It is time to think about a campaign in this city to seriously challenge this massive injustice by demanding that empty condos be used to house the homeless.

A Campaign to Take Housing

The concept of squatters’ rights has never made the kind of gains in Canada that were achieved in a number of European countries. Still, in my work with OCAP, I’ve had some involvement with trying to take over empty properties to provide housing. In some cases, the actions pressured the authorities into creating housing on the sites. In the case of the Pope Squat, the property was held for some months. However, after several of these actions, it was clear that the police would not allow us to hold the properties and that, without a base of active support much larger than we had, squat actions were not viable for the foreseeable future.

I don’t preclude the notion of some symbolic short term housing takeovers to build momentum but, fundamentally, a campaign of action challenging the scandal of empty condos needs to do more than make a point. In the 1930s, the unemployed movements of the day, took action to try and block evictions. By no means did they always succeed but the ongoing resistance made a difference. The landlords and the authorities that served their interests had to reckon with that resistance and the rights of property, exercised at the expense of the impoverished, faced a real challenge. At the moment, speculators can buy up condos in Toronto and leave them sitting empty at will. That could be changed and these parasites forced to reckon with the ever present possibility that homeless people and their allies might challenge their greedy and disgusting squandering of a vital social resource.

Such a campaign would need a core of activists with a much larger base of support. Public meetings could be held to make the case for opening the empty condos. Local committees could be formed to begin to target particular condo developments. The demands of the campaign could be put before the various levels of government and condominium corporations by way of formal deputations and public protests. The idea would be to build an active base large enough that, when action was taken around empty condos, enough supporters would be ready to turn out to transform the initiative into a mass action.

Whether or not it actually proved possible to get homeless people housed directly in empty condos, if such an effort were taken up on large scale and a sustained basis, the pressure on the authorities to provide alternatives would be considerable. In both individual actions and, in the course of the campaign generally, the issue would be ‘If it’s not here, then where is the housing for these people?’ Housing that sits empty so that speculators can enrich themselves, while pushing up housing prices, is an ugly Achilles Heel of the neoliberal city that we would be targeting in a direct and compelling way. With this approach we could create a crisis for big property owners and their political enablers out of which concessions on housing could be won that were significant enough to address the unfolding disaster of homelessness in Toronto. •