Human Rights and Housing

“Shelter and housing can and should be a basic human right,” said Pastor Mark, invoking also John Lennon’s ‘Imagine’ to move his audience to continue the drive by the non-profit sector to provide affordable and supportive housing for those in need. We were gathered at St. Peter’s Evangelical Lutheran Church in downtown Kitchener, Ontario, to mark the official ‘ground-breaking’ of partner Christian charity Indwell’s 41-unit supportive housing project. The mood was celebratory, if also reflective, loving, and committed, in the best Christian tradition. I grew up in that tradition. It moved me too.

That background is also, no doubt, why it was Dom Hélder Câmara’s famous words that came back to me listening to the speakers, not least of them Pastor Mark.

“When I give food to the poor, I am called a saint.

When I ask why the poor have no food, I am called a communist.”

‘Communism’ and Human Rights

Those remembered words recall, in turn, what I will refer to as the ‘conjunction’ of ‘communism’ and human rights. No, I am not referring to US Republicans’ penchant for regarding the idea of ‘human rights’ as itself a ‘communist’ conspiracy, just the kind of thing you’d expect in ‘socialist Canada’. No, I’m thinking back to 10 December 1948 when the nations of the world under the aegis of the United Nations proclaimed the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). That wondrous aspirational document included, as part 1 of Article 25, the following:

“Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond his control” (emphasis added).

Notice the beautiful, unqualified simplicity of the statement: everyone, without exceptions, without conditions, has the right, not because they are deserving (implying there are those who are un-deserving), not only as long as they work hard (implying the lazy and indigent are out of luck), not because they are citizens (therefore, tough on the undocumented migrant or refugee), but because they are human. And notice, too, that the article includes housing as a human right. Yes, in 1948, a mere 75 years ago.

OK, but where does ‘communism’ come in? Well, consider the historical context. The UDHR was promulgated in 1948 by the United Nations (UN), the international body created in 1945 at the end of the Second World War (in Europe). If it was the intervention in the War by the United States in December 1941, following Japan’s attack on the US naval base at Pearl Harbour in Hawai’i, that swung the conflict in favour of the Allies in Western Europe, it was the sacrificial defence and subsequent repulsion of the Nazi army in Eastern Europe by the Soviet Union that won the War for the Allies in the end. That not only meant that the Soviet Union (subsequently, Russia) became one of the five permanent members of the UN Security Council but also that ‘communism’ gained considerable global prestige on the world stage (indeed, setting that stage for the ensuing Cold War between the Capitalist West led by the United States, emerging from the hot War as the most powerful country in the world, and the Communist East led by the Soviet Union).

That Cold War is already presaged in the UDHR itself. For not only does the declaration not have the force of law – being adopted by the UN General Assembly as a statement of principle only – but it includes as part 1 of Article 17 the right that is crucial from the Capitalist West’s point of view:

“Everyone has the right to own property alone as well as in association with others.”

That innocuous phrase, “in association with others,” establishes the place of the capitalist corporation as a rights-bearing “person.”

“In 1886 the US Supreme Court ruled for the first time, without argument, that business corporations were entitled, as ‘persons’, to protection from the arbitrary authority of the states under the Fourteenth Amendment of the US Constitution, an amendment intended for the protection of freed slaves” (Noble, 2005, p. 117).

This means, in the end, that the formulation of the UDHR reflects the West’s determination to keep ‘communism’ at bay by making what it regards as concessions to the demand by the people of the world to establish a world order in which the immense privations of both the Great Depression of the 1930s and WW2 itself could not only not be repeated, but also be overcome in the name of social and economic equality. Yes, we the people could be granted “rights,” including those stated in Article 25, but only notionally, and only alongside the same rights accorded to the capitalist corporation, which effectively circumscribes the scope of the rights accorded to actual people (Teeple, 2004).

This ‘compromise’ was made further evident in the International Covenant of Economic, Social and Cultural Rights of 1966, in which the UDHR’s Article 25 is effectively repeated as part 1 of Article 11:

“The States Parties to the present Covenant recognize the right of everyone to an adequate standard of living for himself and his family, including adequate food, clothing and housing, and to the continuous improvement of living conditions. The States Parties will take appropriate steps to ensure the realization of this right, recognizing to this effect the essential importance of international co-operation based on free consent” (emphasis added).

The Covenant, like its sister International Covenant of Civil and Political Rights, while representing a step forward from the UDHR by being a treaty enforceable in principle under international law, is made moot by including in part 1 of Article 2 the following highlighted provisions:

“Each State Party to the present Covenant undertakes to take steps, individually and through international assistance and co-operation, especially economic and technical, to the maximum of its available resources, with a view to achieving progressively the full realization of the rights recognized in the present Covenant by all appropriate means, including particularly the adoption of legislative measures” (emphasis added).

Canada ratified the Covenant; it came into force in 1976, a mere 47 years ago. As a result, the State is required to submit regular reports to the UN Committee overseeing nations’ compliance with the Covenant, detailing how well it is doing “tak(ing) steps … to the maximum of its available resources, with a view to achieving progressively the full realization of the rights …”

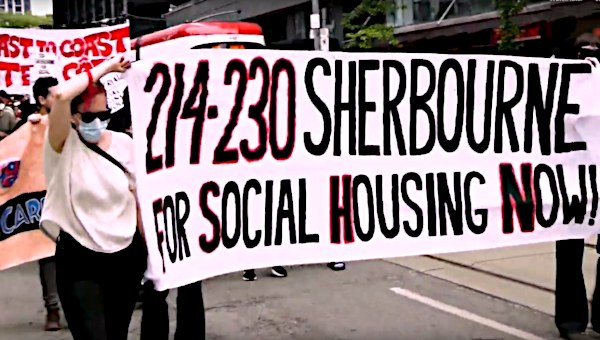

Housing Today

And so it is that, 75 and 47 years later, there can be a worsening national affordable housing and homelessness crisis at the same time as the human right to housing is re-discovered – assisted in Canada, indeed in Kitchener, by the hard-hitting documentary Push by Toronto’s own Leilani Farha, the former UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Adequate Housing.

This situation of repeatedly stated but permanently unfulfilled human rights aspirations has been captured unforgettably in these words of Wallace Shawn from his play The Fever:

“And so, in our frozen world, our silent world, we have to talk to the poor. Talk, listen, clarify, explain. They want things to be different. They want change. And so, we say, ‘Yes’. Change. But not violent change. Not theft, not revolt, not revenge. Instead, listen to the idea of gradual change. Change that will help you, but that won’t hurt us. Morality. Law. Gradual change. We explain it all: a two-sided contract: we’ll give you things, many things, but in exchange, you must accept that you don’t have the right just to take what you want. We’re going to give you wonderful things. Sit down, wait, don’t try to grab. The most important thing is patience, waiting. We’re going to give you much much more than you’re getting now, but there are certain things that must happen first – these are the things for which we must wait. First, we have to make more and we have to grow more, so more will be available for us to give. Otherwise, if we give you more, we’ll have less. When we make more and we grow more, we can all have more – some of the increase can go to you. But the other thing is, once there is more, we have to make sure that morality prevails. Morality is the key. Last year, we made more and we grew more, but we didn’t give you more. All of the increase was kept for ourselves. That was wrong. The same thing happened the year before, and the year before that. We have to convince everyone to accept morality and next year give some of the increase to you” (Shawn, 1991, pp. 50-51).

Since at least 1948, and more pointedly, since the late 1970s following the collapse of the welfare state and the coming of neoliberalism (“promotion of the primacy of private property rights”) under the name of ‘globalization’ (Teeple, 1995, p. 76), the rulers of the world – the capitalist plutocrats and their complicit enablers – have been engaged in what is effectively a class war to prevent, at worst, and take back, at best, any moves on the global stage to establish economic democracy – that is, the rule by the common people (the meaning of ‘democracy’) over their material circumstances, otherwise known as ‘communism.’ That means keeping the levers of power out of the hands of the people at large by keeping just enough of them affluent enough to keep buying into the system, and enough of them just poor enough to fear losing what little they have from taking things into their own hands.

And so it is that housing remains – in fact, is increasingly treated as – both a speculative or an investment commodity for the rich and satisfied, and a charitable donation for the poor and precarious, in a system of corporate capitalist rule obfuscated by the language of human rights. •

References:

- Noble, David F. Beyond the Promised Land: The Movement and the Myth. Toronto, ON: Between the Lines, 2005.

- Shawn, Wallace. The Fever. New York: Noonday Press, 1991.

- Teeple, Gary. Globalization and the Decline of Social Reform. Toronto, ON: Garamond Press, 1995.

- Teeple, Gary. The Riddle of Human Rights. Aurora, ON: Garamond Press, 2004.