Ontario 2020 Budget

“We are here at a critical time; not just for Ontario but for the whole country. And during this difficult time, my government’s top priority is the health and well-being of all Ontarians. Moments of urgency require us to put aside our differences, have each other’s backs, stick together as a country, and reassure the people of Ontario, and the people of Canada, that we’re all in this together.” – Ontario Premier Doug Ford, March 2020.

In the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, government officials across Canada employed lofty rhetoric, often drawing on themes of unity and collective well-being. The federal government even bowed to pressure to create direct funding programs for workers and students facing employment challenges, along with its support programs for businesses. Eight months on, without certainty of a vaccine in the near future, the conditions in Ontario remain, by many assessments, bleak. Thousands of people have been infected by the virus. Millions more have faced economic and social challenges unseen in generations. In most cases, the speeches by political leaders calling for unity have faded, and have been replaced with a focus on economic re-opening. And the virus remains.

This was the backdrop for Ontario’s long-delayed provincial budget, released on November 5 by the Doug Ford-led majority Progressive Conservative Party government. If the budget tells us anything, it is that the neoliberal agenda that has for decades dominated Ontario’s politics endures. The government has made clear it will do what it can to facilitate capitalist profitability and intensify the infiltration of market logic. The people will suffer the consequences.

At the time of this writing, more than 3,300 Ontarians had died due to the pandemic, amid more than 95,000 total cases. Workers have also been hit hard by the recession that has come in the wake of the pandemic. Ontario’s seasonally adjusted unemployment rate was 9.6 per cent in October – an 85 per cent increase since January’s rate of 5.2 per cent. The pandemic recession has also disproportionately affected women workers. Since February, in the majority of months, the unemployment rate in Ontario for women has been higher than that for men. Importantly, amid major changes to how education is delivered, many women have been left to shoulder the social reproduction tasks of full-time homeschooling and childcare amid the pandemic. This setting is raising barriers to their re-entry to a labour market that has been located by the province at the centre of the recovery agenda. In Toronto, data reveals that the pandemic has disproportionately affected low-income and racialized people.

Historical Context

To place the 2020 budget in proper historical context is to attempt an understanding of the metamorphosing neoliberal moment of capitalism. In other words, it is to grasp for the substantial changes in the patterns of qualitative public policy and quantitative spending by the provincial state. The changes have been especially significant in Ontario in the past three decades. During that time, Ontario, like many regions, has felt the effects of an increasingly internationalized trade regime and a reduction in mass-production manufacturing employment. Provincial governments have responded to economic and social shocks differently, but an overarching paradigm that cuts across all of the particular governments-of-the-day has emerged.

In terms of governance strategy, neoliberalism in Ontario can be understood as the provincial state working to facilitate the intensification of the market’s role and of individual competition logic, both within the state itself and throughout society – while de-prioritizing its own role in social provisioning. Historical context does not absolve the current government of its choices. However, the genesis of neoliberal governing in Ontario predates the current regime and implicates governments formed by all of the major provincial parties: New Democratic, Progressive Conservative, and Liberal. Each party has, in its own way, enacted policies that have made Ontario a province that prefers austerity to a robust public service, privatization to public ownership, and a region with the lowest per capita government program spending in the country that looks to the market to manage crises.

Pandemic notwithstanding, that pattern has continued. Amid lockdowns, job losses, and social distancing, Ontario did not create a direct relief scheme for workers similar to those at the federal level or introduced in British Columbia – although it did loosen rules for accessing its emergency assistance program. That program, which is run through Ontario Works, offers significantly less money than offered in British Columbia. Throughout the spring, families with children were offered a one-time payment to assist with the move to online education. The province also allocated extra funding to low-income seniors, and a brief suspension of student loan repayments, some emergency job leave protection for workers ordered into quarantine, and a job retraining fund were put into place. Businesses were given tax cuts and deferrals. Ontario released a list of “essential” services, which were permitted to remain open, including grocery stores, gas stations, and pharmacies. Notably, the list also included residential construction and capital markets such as the Toronto Stock Exchange. On April 27, the Ford government already had released a comprehensive plan to re-open the economy in stages, revealing their thinking and priorities.

Provincial finances have also been shocked by the pandemic. In October, Ontario’s Financial Accountability Office released a report which detailed provincial finances and painted a dark picture: it projected the provincial unemployment rate could hit 9.7 per cent in 2020; it noted that in September there were 318,500 fewer jobs in the province than in February; it projected a fall in real GDP of 6.8 per cent – and it noted that provincial revenues have collapsed. Importantly, revenues from the Corporations Tax revenue were projected to plunge by $6.6-billion, while Personal Income Tax was expected to be down another $6.7-billion. Sales Tax revenues were projected to fall by $2.1-billion. While some of the revenue lost is expected to be offset by federal transfer payments, the report concluded that Ontario will ultimately be down more than $6.5-billion in revenue in 2020-21. Significantly, the report also flagged $9-billion in increased budgeted program spending left unallocated by the government.

Release the Budget

Finally, on November 5, the long-awaited Ontario budget was introduced – on a day during which 381 people were reported hospitalized in the province with COVID-19. Several key themes can be identified: direct provisioning; public service investment; and support for business. In terms of direct provisioning, the province argued it has set aside $33.4-billion in “direct support.” However, much of that support was identified as arriving indirectly through tax relief and deferrals. Perhaps the most significant direct provisioning item is the reintroduction of the education-cost payment support program for families with children. There was no pandemic relief fund for workers. With an agenda to re-open the economy, despite average case counts exceeding 1,000 as of this writing, it appears any hope of Ontario offering emergency direct relief for workers who have lost their jobs should be squashed.

As for program investment, the budget showed no increase to either Ontario Works or the Ontario Disability Support Program. However, before the budget, the province moved to increase surveillance of people accessing social assistance. The budget did identify $7.5-billion in new funding over three years for investment into health – including an additional $2.5-billion for hospitals this year. Also, while the province announced $1.75-billion to increase the number of long-term care beds, specific details about how Ontario will deliver on an announced plan to provide a new average of four hours’ worth of long-term care per day for the sector, which has been a major pandemic hotspot, were absent in the budget document.

Finally, in terms of support for business, the province offered a collection of tax breaks. Those breaks include exempting 90 per cent of businesses in the province from paying Employer Health Tax and thus contributing to the Ontario Health Insurance Plan, as well as lowering the Business Education Tax rate for 94 per cent of businesses. Industry was also offered significant hydro subsidies. Another move by the province was to introduce a scheme to provide support for tourism expenses in 2021. The minimum wage, however, increased by a mere 25 cents on October 30. The government projected a $38.5-billion deficit for 2020-21, and deficits into at least 2023.

Critics assailed the budget. Ricardo Tranjan, a political economist at the Ontario office of the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives called the announcement “an austerity budget”; while Sheila Block, the office’s senior economist, noted “the government has made no effort to raise money for the COVID fightback: there are no new taxes on those high-income earners who have kept their jobs and their incomes since the pandemic began.” Social Planning Toronto said the province “fell noticeably short when it came to supporting Ontario’s nonprofit sector.” Organized labour also met the budget with skepticism. The provincial government has “abandoned parents and educators who are left to ensure that students have what they need under extremely challenging conditions,” said Sam Hammond, president of the Elementary Teachers Federation of Ontario. And Fred Hahn, president of CUPE Ontario, which represents thousands of health care workers, described the budget as “clearly based on the tired, old, ideological assumption that cutting taxes will trickle down to make life better,” which, he added, is “a fantasy.”

By contrast, the Ontario Chamber of Commerce cheered the budget. “This Budget addresses many of the actions we, on behalf of Ontario’s business community, have been asking for,” said Rocco Rossi, the chamber’s president and chief executive officer. Similarly, Dennis Darby, the president and CEO of Canadian Manufacturers & Exporters welcomed the “significant measures to improve business competitiveness and support innovation for Ontario’s manufacturers.”

Several conclusions can be drawn from Ontario’s pandemic budget. First, the government has made the market the epicentre of recovery, and working-class Ontarians, not in a position to stay at home, have been abandoned. Second, pandemic neoliberalism has a significant qualitative difference than neoliberalism in its previous forms, given the large-scale repercussions across society. And third, any meaningful opposition to pandemic neoliberalism will have to come from civil society – and outside of the legislature.

The Ford-led PC Party has unequivocally chosen the market as its pandemic saviour. Instead of choosing to develop social infrastructure that can more fairly redistribute wealth amid mitigate mounting unemployment, sickness, and poverty, the government has intensified its reliance on private accumulation and profit-taking. This will not provide a fair recovery for vast numbers of people in Ontario. And it is not designed to. But the market cannot function without labour to generate wealth. Scores of workers in this province have been on the front lines of the pandemic since the beginning, stocking grocery shelves, preparing take-out meals, and delivering good and services. Capitalism requires the exploitation of labour power to remain sustainable. Despite requests by some medical experts for more time to safeguard public health, the government’s rush to re-open the economy is a clear indication that it will not allow profitability to be significantly curtailed, or for the conditions to form for a more redistributive society.

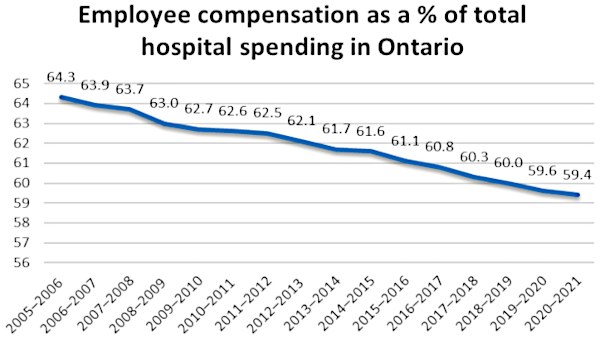

Also, what sets pandemic neoliberalism apart from some of its previous mutations is that the cost of state retreat from adequate provisioning has become generalized in an immediate way. The evidence shows clearly that the pandemic has disproportionately hammered low-income and racialized people. The sheer scale of unemployment, rate of infection, and death has also reached into millions of homes right away. Assessing the permanent consequences of the pandemic on mental and physical health, families, employment, and public finance in Ontario will take years. It is true that the government has provided new money in the budget for hospitals. However, one of the effects of investing in hospitals while simultaneously re-opening the economy during a pandemic is that public health funds work to subsidize private industry by treating people who get sick while in the process of consuming goods and services. In this way, the government has facilitated market profitability – a hallmark of neoliberal governance.

Finally, with a majority government in the Legislature, the PC Party enjoys little functional obstruction from opposition parties to its business-first pandemic agenda. In this situation, the burden of opposition falls to civil society. Organized labour, which represents thousands of front-line workers risking their health for private accumulation, and social movements have been vocal about their opposition to the government’s agenda. At this stage, the government does not seem to be listening. Civil society in Ontario has resisted harsh neoliberalism before. The situation in Ontario is becoming increasingly desperate, and the provincial budget does little to help most people. But a better, fairer Ontario can be won. •