Challenges and Openings for the Free Transit Movement in Toronto

Toronto is Canada’s largest city, with a population of 2.7 million (and over 6 million in the Greater Toronto Area). Its public transit system is the third largest in North America, after New York City and Mexico City. It is made up of four subway lines, 11 streetcar routes; and over 140 bus routes. The city transit system is run by the Toronto Transit Commission (TTC), which is responsible to the Toronto city government. There are also public transit stops for the regional system, called GO, which, in turn, is managed by the regional transit authority Metrolinx, which is responsible to the province of Ontario. Suburban regions and municipalities have their own operators. Compared to them, as well as GO, the TTC carries by far the most passengers.

While massively used, the Toronto transit system is chronically underfunded, both absolutely, and in comparison, with other transit systems. The subsidy per rider was approximately $1.07 in 2019, up from the traditional levels, but below the historical average of around $2.50.

The subsidy is key, as public transit operations can never be fully paid for by fares. But, the Toronto “fare-box ratio” – that is, the percentage of operating funds that come from fares, is around 67.4 per cent – also the highest in North America. This is due to the low levels of government subsidy from both the city and the province.

Increasing Fares

Not surprisingly, fares have risen in recent years, as well, from $2.10 per ride in 2006, to $3.25 for adult cash fares in 2020 and slightly less for other modes of payment. The city has a monthly fare for seniors and students at a 20 per cent reduction and a $2.30 individual fare. A low-income fare was also put in place in 2018, initially set at the current senior fare level, but due to be brought forward in stages, from the current coverage of social assistance recipients, to eventually cover all people on low income. (This is still far from the demand raised by the transit movement for free fares for social assistance recipients, and $50 monthly fares for those on low income.) However, the continuation of even the present level of funding for the low-income passes is far from assured.

Toronto’s transit system is also uneven in its outreach to different class fractions and neighbourhoods. In the downtown core of the city, rapid mass transit is dense, but in the so-called inner suburbs – formerly independent municipalities, amalgamated into the larger city of Toronto – there is an overreliance on buses and private cars. Due to socio-economic trends associated with neoliberal urban development, many of these areas are home to an increasing concentration of poor and low-income people, often from racialized communities. In other parts of the GTA (as in most parts of Canada, except in the largest cities), transit reliance is much lower in proportion to the overall population. The vast majority of commuters drive private cars.

For a number of decades, there was little investment in new mass transit, but in the past few years, the province and city have reintroduced plans to building both downtown and the inner suburbs. However, bitter fights have developed over the form of new transit and funding. These are often related to divisions between those who are dependent on private cars and those who use buses, those for whom public transit is the primary form of mobility and those who rarely use them, and those for whom the cost of transit is minimal and those who find it too expensive – all of this in relation to a mode of transportation that is often overcrowded, slow, and unreliable, but a key foundation of public transit.

Free Transit Toronto (FTT) is a movement dedicated to promoting the idea of fare-free public transit in the city of Toronto. It was originally part of a larger political experiment called the Greater Toronto Workers’ Assembly (GTWA), launched in 2009. The GTWA brought together much of the Toronto socialist and anti-capitalist left in an attempt to bridge the differences between the components of the working class, in a project challenging neoliberalism and the limits of social democracy.

One of the projects of the Assembly was to develop a campaign that could mobilize major working-class constituencies and fight for a demand that could push toward key structural reforms. As well, we wanted to build a movement to challenge neoliberal urban practises and structures: privatization, radical cuts to collective public services, attacks on unionized labour, precarity, racial and gender discrimination, deteriorating housing patterns, etc. We also wanted to craft a campaign that was “ours” and could help build and consolidate the Assembly project.

We wanted to work within a framework inspired by the “Right to the City” movement, contributed by David Harvey (based on an original book by Henri Lefevre), which emphasized a different vision of urban life, one shaped by public and collective services for the people who live and work there, not the neoliberal urban vision of corporate headquarters, offices, and condo developers. Finally, we wanted to sponsor a campaign that raised fundamental questions about capitalism.

After a few months of debating about which campaign to adopt, and after a series of discussions, we chose a Free Transit Campaign. This decision met with considerable dissent. Some argued that it was too radical a demand and wouldn’t find any real traction. Others argued that the transit workers’ union would never support a campaign to eliminate fares, and they didn’t want the union to come out in opposition to the campaign. In any event, we decided to build our own campaign for Free Transit.

Our inspiration was the successful example of the Los Angeles Bus Riders Union’s effort to organize working-class people to demand affordable and accessible public transit, and larger efforts to actually apply a radical and anti-capitalist perspective to struggles over a central component of peoples’ lives – public transit.

Building the Campaign – Creating a Footprint

As we began, we realized that we knew a lot more about fighting for decommodified public services in general than how our knowledge might be applied to public transit. In an environment where important new and rather fierce political debates raged about how to expand a public transit network that had not seen any appreciable investment in the previous 20 years and where fares had been steadily increasing, we were way behind the curve ball when it came to understanding the concrete issues involved in actual Toronto public transit and the TTC.

We started reading-up on the history and then-current contextual realities of Toronto transit issues and debates, but we concentrated on getting the principle of fee transit “out there.” Public transit needed to be treated as a fully funded public service, such as Medicare and the public library system, without user fees. We organized a series of public rallies, introducing our campaign (all in the student-heavy downtown communities, which were in our comfort level), and produced pamphlets and fact sheets about the principles underlying free transit, with examples of international cities that had either completely free transit or partial fare-free service.

We engaged in some extremely creative tactics to popularize the idea of free transit. We boarded subways and buses – as paid users, of course – and performed street-theatre vignettes, and then spoke with passengers about free transit, handing out literature and listening to transit users’ responses to the points we raised. We found that people, for the most part, thought the idea was interesting, new, fresh, but utopian. People asked us how it would be possible to raise the funds for such a project, how to address other concerns about public transit such as getting decent service, building reliable mass transit in the inner suburban areas where many low-income working-class people live, and, in the short term, lowering fares.

We also created displays for use at transit stops, shopping centres, schools, and various kinds of public meetings. We were able to get noticed on various alternative media outlets (university, community, etc.), and we produced more in-depth materials, addressing many of the issues raised by transit users in our outreach work.

In that first period, we attracted a number of future activists – some older, some younger – who were intrigued by the idea of free transit, and who were committed to the idea of fighting to decommodify public services. Most were either students or people attached to the labour or environmental movement. We all grew together in building the movement.

We were able to participate in a number of international sessions where we exchanged experiences with others engaged in free transit campaigns: one in Stuttgart, Germany in 2010, and another conference specifically on Free Transit movements in Toronto in 2013. We also produced a number of longer pieces of literature on Free Transit and its necessary interrelation to a larger, eco-socialist analysis of urban life.

A call for decommodifying public transit only makes sense in relation to a larger urban agenda, one that includes massive funding through progressive taxation by higher levels of government, as well as the city. This requires major changes to existing political and administrative institutions. Building mass transit on the scale required to make it work calls for challenging existing patterns of urban geography and car dependency. It would require the creation of publicly owned and democratically controlled financial institutions of some sort and government willingness to borrow on a scale comparable to the mobilization of the wartime era. The dominance of existing elites, such as private developers, financial capital, and the beneficiaries of the P3 (public-private partnerships, amounting to privatization) craze would have to be challenged. New capacities to build, manage, and plan, which require both expertise and popular participation, would have to be developed.

The dominant economic activities currently operating in our city would have to be transformed and replaced with popular service provision, production of ecologically necessary materials, and other popularly determined activities. Housing would have to be affordable, public, and co-operative, and developed and shaped according to working peoples’ needs. What is known as ‘gentrification’ would have to be replaced by designs of livable and exciting city life, not based on wealth. Land municipalization, as well as rent controls, would all be in the mix. Finally, there would have to be democratic forms of planning and input, so people of all incomes and neighbourhoods would have input on mobility levels and public transit planning. Many of these issues were integrated into our materials.

One of our most successful actions was a demand for free transit on days when the city declared heat or cold alerts. Low-income people needed to have access to cooling or heated shelters, and public transit was essential in those instances. In partnership with a coalition of social activists working for low-income passes – the Fair Fare Coalition (FFC) – we organized a protest at a central four-stoplight corner/intersection in the city centre and marched with a cardboard replica of a subway car – courtesy of the FFC. It got lots of publicity and helped to introduce the demand for low-income fares into the larger discourse of the city transit discussions.

Hitting a Ceiling – Branching Out Into the Movement

At a certain point, the Free Transit Campaign hit a ceiling: our educational work did not bring in new members; the relatively small group that had organized around the campaign remained the same, with activists coming and going around it. It was seen more as a novelty than a growing campaign. As well, we had no success in building links with the transit union or with dissident movements/members inside the union. We never had a confrontation, but the leaders were cold to our message, although the drivers and TTC workers we encountered in our activities were always friendly.

As well, a small number of activists floated the idea of trying to build around a mass-transit users movement, called TTCriders, which, at the time, was mostly a paper group that solicited petitions against fare increases and did educational work around the need to build a Light Rapid Transit (LRT) network across the city. It was tied to the Labour Council and the Toronto Environmental Alliance (TEA) but did little organizing and had no membership infrastructure. Those activists working to build it were supportive of our movement and encouraged us to work with them.

After a series of meetings, we decided to help to build TTCriders as a democratic and mass-based organization, and influence its structure, program, direction, and larger orientation, all the while maintaining the independence of our Free Transit Campaign.

We engaged in the initial debates over the structure of TTCriders, and in particular, helped argue for an emphasis on lowering fares, increasing the reach of new mass transit to working-class communities across the city, and improving the quality and accessibility of public transit. These were not “motherhood” issues: there were those who argued against lowering fares (either calling for freezing, or ignoring the issue), in the name of accepting the limitations of what’s ‘possible’ in the medium and short term, reluctant to identify with working-class interests and needs. We were not alone in arguing for the kind of organization that concentrated more on activism than lobbying. The newly transformed TTCriders attracted young and energetic participants, and was led by an extraordinarily talented politically independent activist, a woman who helped pull it together. After a number of years as a staff person and leader, she eventually ran for and won a seat in the Ontario provincial legislature for the social democratic New Democratic Party (NDP), becoming the opposition transit critic.

Most of the Free Transit activists were central in helping to build TTCriders. During this period, we combined our efforts in producing independent materials, power-point presentations at activist movement spaces (fighting municipal cutbacks; Popular Summit activities, etc.), and discussing and planning strategic approaches to our work in TTCriders and the broader transit movement.

Combining the Long and Short-Term

In the following years, TTCriders grew, as did our participation in it. We continued to argue for and help develop collective rallies and mass actions; opposing Public-Private Partnerships (P3s) and privatization (an approach increasingly embraced by the political and economic elite in the city); emphasizing work in, and building in, lower-income and ethnically diverse working-class communities; building across different components of the working class; intervening a particular way in the critical debates of the time (how to grow, how should ordinary working people shape or participate in these processes, gentrification, etc.).

In the process, we struggled to find a way to both shape and build the larger movement, on the one hand, and, on the other, maintain our independent voice and influence and grow as an independent Free Transit movement. Much of our energy and minimal resources went into building the campaign for low-income fares (with the critical ideological underpinnings of arguing for a public transit system that acts as a public right, rather than a paid service for “customers”); emphasizing building in communities and within the working class, rather than giving deputations, lobbying, and developing relationships with elected political decision-makers (all of which are certainly necessary), and, as part of TTCriders, fighting for adequate funding from the city, province, and federal governments.

The Fair Fare Coalition became part of TTCriders and organized a more ambitious campaign for low-income passes. After a series of consultations with low-income organizations and individuals, it developed demands for free transit for people on social assistance, and $50 annual passes for people on low income. We then organized a number of large protests at City Hall, demanding, and eventually winning, a commitment to develop a low-income fare. It is extremely modest, will not cover all of the low-income users who need it, and will not be applied in a timely manner. But it was a major step forward, and our work helped to inspire, shape and win it.

On the other hand, much of our independent activity was reduced, in favour of shaping the orientation of TTCriders and the Fair Fare Coalition. We started to work on our website, making stickers calling for free transit, and producing a blog, but most of the independent work became subsumed into our TTCrider work.

In March 2015, children under 12 were given the right to ride free – a move unilaterally enacted by the conservative Mayor. While it was done as a way to mitigate the city government’s unwillingness to raise taxes to pay for transit, it was an important step forward, which introduced a limited experience with free transit.

Ongoing Challenges and Openings

The GTWA dissolved in 2016, and the Free Transit Campaign continued to operate as the Free Transit Toronto. We continued to meet and face the ongoing dilemma of how to build an independent movement for a decommodified mass transit system, all the while organizing in the short and medium term for better, cheaper, and accessible transit, in the context of a larger public transit movement.

However, by the latter part of 2019, the context began to change. In the face of a Progressive Conservative provincial government committed to austerity, P3 and private sector models for transit, as well as threats to take ownership of the Toronto subway system, anger and frustration began to grow with the status quo in Toronto’s transit environment. The government’s refusal to pay a needed proportion of the costs of operations, as well as capital spending, drew in new layers of transit activists. This was all compounded by the unilateral cutting in half of Toronto’s City Council representatives.

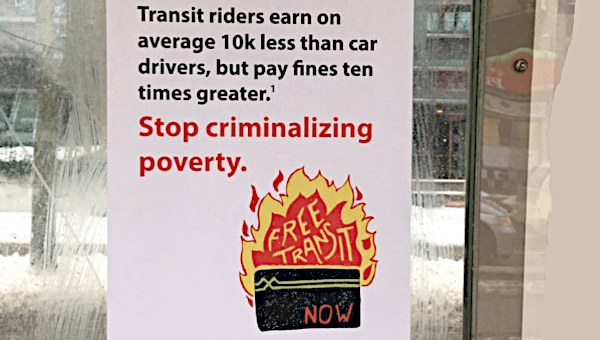

Meanwhile, the Toronto Transit Commission, with its overall dependence on fare collection hired fare inspection police, ostensibly to combat ‘massive’ fare evasion. While the percentages of fare revenues lost to evasion were not fundamentally different than comparable transit systems, the transit management doubled-down on their campaign, not surprisingly targeting low-income youth, predominantly Black transit users. TTCriders countered with a campaign against “the real transit fare evaders,” the provincial government and the premier, for not funding Toronto transit.

Calls for free transit became more and more frequent from social activist movements across the city and in other transit-strapped communities. Political parties, notably some NDP, Liberals and independent municipal candidates called for free transit in various election campaigns. The advent of the climate justice strikes – schools were closed by student strikes, supported by parents and teachers, demanding action on climate change – added to the new legitimacy of the call for fare free transit.

The Amalgamated Transit Union (ATU), Local 113, the transit workers union, in Toronto and across the country, was in the process of reform and began a new era of transit activism, centred around opposition to privatization, supporting TTCriders and similar movements, and abandoning their opposition to moving toward free transit.

Free Transit movements in Ottawa, Oshawa, and in other parts of the country began talking about building a larger and more co-ordinated movement. Free Transit Toronto issued invitations to members of the activist community and across the province to form a larger coalition of groups and individuals to agitate for free transit. Groups such as Climate Justice Toronto, Courage Coalition, TTCriders, Jane Finch Action Against Poverty, Socialist Project, as well as Free Transit Ottawa and We Are Oshawa, all helped to pull it together. A series of meeting were held in January and February to discuss and debate common principles and the challenges of forming a structured movement for free transit.

In the midst of this process, the pandemic crisis hit, and once again affected the direction of the movement. Meetings became “virtual” and discussions about principles and structure slowed down somewhat. Public transit across the country, but in particular in Toronto, faced a new set of crises: 80% loss of transit users, demands for protective equipment from transit workers and users, the overreliance of front-line health care and other workers in the pandemic, and the dramatic loss of resources and funding for public transit.

TTCriders and a number of sister organizations across the country initiated a movement to demand emergency funding to make up for the loss of revenue for transit, as well as to demand regular provincial and federal funding after the pandemic, and, for Toronto, the immediate introduction of new priority bus lanes to serve front-line and other workers using transit. Then, the TTC loosened up its fare-enforcement policies on buses and streetcars, and Free Transit Toronto and the new coalition issued statements in solidarity with the larger movement, but also demanding that fare remain free and lowered once the pandemic came to an end.

Another development in this period has been the growing movement against structural racism in policing bodies, along with demands to dramatically reduce funding for policing and the carceral structures and replace them with alternative means of dealing with social contradictions. In the midst of this movement, the TTC announced it would re-engage fare-enforcement cops to enforce fare payment. The new coalition, along with TTCriders and Free Transit Toronto, opposed this move and made plans for a series of actions to challenge it, tying the new enforcement regime to the ongoing oppression of low-income transit users, and especially, people in communities of colour.

Long Term Challenges

The deeper challenges remain. In an era where there are no socialist political parties – hegemony on the left remains within the social democrats and various anarchist orientations – an organization fighting for free transit is working without political support. There are almost no reference points within working class institutions and communities that argue for the kinds of massive changes that free transit would need to become a reality – and that it could initiate. There are movements around housing, tax fairness, anti-poverty, the environment, but they remain separate from a larger political orientation that is left of social democracy. Individual activists with more radical perspectives work across the city, but the focus remains on short-term, incremental improvements that accept the larger signposts of the status quo.

The opposition to some of the main lacunae in the government’s responses to the pandemic emergency has energized and radicalized certain nodes of social activism, such as amongst organizations such as the Ontario Health Coalition, groups representing non-unionized workers, tenants, and those advocating for the health and safety of front line workers. The labour movement has remained, except for certain spokespeople, weakened and defensive.

It would be fair to say that within the social democratic community in the city (city politics are officially “non-partisan”), there is a left wing. Some of its members do call for the kind of taxation instruments that could provide resources for expanded and more affordable public transit. But these people are far from the majority within the social democrats, and refuse to build a more radical program around reduced transit fares (let alone, free transit), massive funding of public transit, and restrictions of private car use, not to mention their hesitancy to initiate or support more radical actions in support of necessary reforms.

Examples of this dilemma are not hard to find. In a recent strategy discussion for TTCriders, we debated whether we should demand or oppose funding for a proposed “relief” subway line, to take the pressure off the main subway artery to the downtown business district – which would relieve overcrowding for the tens of thousands of people coming to work from both the affluent suburbs, and less affluent areas. It was argued that, instead, we should call for funding a needed light rail line that would serve a current transit desert in the inner-suburban, working class neighbourhoods. The debate was framed in terms of what we can “afford” to pay for, given the current funding plans from the city, province, and federal government, rather than what we “need” and could afford, if we challenged the current deficit obsession, and the austerity model it entails.

In the current political moment, challenging a presumed austerity drive in the post-pandemic era to come is essential and will be a theme of progressive activists and advocates. But opposing a renewal of austerity is really not enough. It requires a longer-term perspective and a commitment for deeper and more fundamental change. The survival of public transit is at stake, given the changes that the pandemic period has brought about in transit usage, work and commuting patterns, the need to protect against a relapse in the virus, and the culture of transit. Both the relief line and the expanded version of the LRT network are possible and necessary – as is our collective responsibility to fight for alternatives to gentrification of lower-income working class neighbourhoods, as part of the battle to win new mass transit.

But in this kind of environment, the Free Transit Toronto and a larger movement we can contribute to building are components for moving beyond the current political limitations. We will continue to weigh-in on key political struggles involving public transit – within and independent of the larger transit movement; defend and expand public transit, which is under threat as a result of the pandemic period; propose and organize for developing public capacities to plan, develop, and build transit (as opposed to P3s); argue for progressive tax reforms and a commitment to replacing car dependence with public transit with all that entails for funding, job creation, and transformation of the structure of the city; oppose the repression and policing of transit users; challenge the elites that run the city’s economy – from the financial interests to the private development industry; and work to root the transit movement in working class communities, where new leaders can be developed to argue for free transit and a larger alternative urban vision.

Keeping alive that vision, all-the-while fighting to defend, enlarge, and deepen public transit, remains our principal challenge. •

This is a revised and updated essay that appeared in Judith Dellheim and Jason Prince, eds., Free Public Transit: And Why We Don’t Pay to Ride Elevators, Montreal: Black Rose Books, 2018.