Two Reports from Chile

The Neoliberal Miracle Under Fire

Unexpected turmoil erupted in Chile on October 18th, when high school students mobilized against a subway fare increase. On October 25th, another two million Chileans joined them in opposition to the impacts of neoliberalism in every aspect of life. They are in revolt against political, social and economic abuses stemming from the commodification of education, health, and retirement pensions.

The international media has published impressive images of the recent events, illustrating the result of years of accrued anger that began with the military dictatorship in 1973 when neoliberal economists, known as the Chicago Boys, used Pinochet’s Chile as a testing ground for their theories on the withdrawal of the state from economic activity. The state’s resources were transferred into private hands to enhance the free market and to further the privatization of common goods and social programs. Neoliberalism put an end to any tenuous forms of social cohesion in Chile.

The current state of social injustice and the profound gap between rich and poor are a shameful platform on which the OECD country continues to expand. Chile ranks as one of the most unequal countries among a group of thirty of the world’s wealthiest nations. Another way to evaluate inequality is by examining the incomes of the richest and poorest citizens. In 2006, the richest 20 per cent earned 10 times more than the poorest 20 per cent, according to a government survey, while the average monthly salary was the equivalent of $750 CAD.

Protesting To Change the Government

The current protests are not just concerned with changing the government; they intend to change everything. Things have been getting progressively worse for decades, and people worry about the future and their children’s wellbeing. Almost everything is privatized in Chile – it is neoliberalism at large, and the slogan “neoliberalism started in Chile and should die here” has swept across the nation-wide demonstrations.

Neoliberal reforms implemented during the dictatorship and continued after the transition to democracy took the form of abuses by the elites against the majority of the working poor, and the years of exclusion and humiliation are taking their toll. People are fed up with seeing the new rich pillage the country’s wealth. They do it in the name of a development system that has enabled the ruling elites to marginalize the poverty and debt of millions of Chileans for their exclusive benefit. This ‘shock doctrine’ was implemented under a brutal authoritarian regime thirty years in the making through the assassination, torture, violation, and exile of its opponents.1 The policy of war applied against the left and popular organizations achieved its goals for many years but now faces the rebellion of the new generations and the ghosts of those defeated in 1973 but who never truly stopped fighting.

All the Power to the Elites

Paraphrasing Pinochet while nodding to von Clausewitz, Chilean President Sebastian Piñera declared on October 20th that “Chile is at war against a powerful enemy,” thereby prolonging the political crisis into one of warlike confrontation.2 Piñera then declared a state of emergency and curfew and called on the military to guard private property. The Chilean Armed Forces were founded to protect the dominant system against any popular social forces which might emerge from abuse and structural injustice and has provided the pretext for the murder, torture, and violation of unarmed civilians, men, and women.3 The only war that Chileans remember is when the armed forces attack peaceful protesters who demand that their rights be respected. Currently, as in the past, the armed forces shoot those who paid for the bullets with their taxes and their labour.

But nothing should astonish us anymore. The history of Chile has shown that when the Right is unable to maintain social hegemony, it exercises domination through state repression. To do this, the government resorts to a fictitious internal enemy or international conspiracy. After 1973, neoliberals reduced the social role of the state and expanded the police services, effectively criminalizing dissent through repression. All other public sector functions were privatized. Neoliberalism continued, regardless of the government in power, because during the military dictatorship the right wing enacted an authoritarian constitution that would control society from above. This constitution is undemocratic both because of the context in which it was created and because of its contents. It restricts popular sovereignty, focusing instead on private property and market freedom against the common good and societal well-being.

Nevertheless, the social rebellion that emerged to challenge to neoliberal democracy and its political institutions is calling on us to build a new collective vision that invites us to rethink and reinvent the geographical territory we inhabit. We no longer know who the country belongs to or where it is heading, but we are not willing to give up without a fight. In order to challenge neoliberal domination from its roots, it is imperative to reimagine the country, its institutions, the role of the economy, the character of citizen participation, the role of indigenous nations and traditional peoples, and the model of development.

The State that neoliberal policies built represents a culture of domination and an economic model aimed at extracting and assuming possession of wealth in all areas of human life. Accumulation through dispossession is a concept developed by David Harvey, which is fully at work in the assault on common goods for the concentration of wealth and the free movement of capital in Chile.4

Resistance from Below

The massive mobilizations taking place in Chile over the past month were entirely spontaneous. They were sparked by young people who jumped the subway turnstiles to protest a minor transit fare hike, and many of these young protestors were treated brutally by the police. People reacted to defend their children, and in a matter of hours, the protests spread through the entire country.

The protestors’ demands are related to minimum wage, pension plans, free education, healthcare, the well-being of retirees, the public management of water, student loans, Indigenous autonomy, anti-patriarchy, fishing matters, children’s rights and protection, forestry management and the lumber industry, corporate tax evasion and illusion, and the role of the state in the economy. The ruling elite has stolen from the people for more than three decades. The fare hike was the last straw.

No one and everyone is leading this fight. The issues are what drive the mobilization, and I have never seen anything like this before. Every movement in Chile has been working to support their shared demands through social networks, including the labour and women’s movements, and the student, indigenous, and environmental movements. However, these movements are not coordinating or organizing these protests: they are truly spontaneous.

The recently organized Social Unity Platform, encompassing these sectors and many other social organizations, is becoming the forum for some form of coordination and has recently called for general strikes in October and November. The masses are in the streets everywhere, making these the largest protests since the fall of the dictatorship. While vandalism and looting have occurred, it is primarily multi-national corporations like Walmart and other local food chains that have been targeted.

Is Chile Going Somewhere?

The President has few options left. The Piñera government has committed serious errors, including infringements to the already biased constitution of an arbitrary State responsive only to the needs of neoliberal policies. His political capital is declining, and his impending resignation is whispered about in the business and military hallways. Citizens are demanding his resignation for the crimes that have taken place. He must be brought before the courts of justice for human rights violations.

The UN Human Rights Commission, as well as the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR), are now in Chile monitoring abuses of power. As a result, the Chilean government has ended the state of emergency and curfew and has reorganized some of the ministries, all while retaining its hard-core neoliberal politicians.

The numbers, however, speak for themselves, indicating the government has little intention of backing down. According to the Human Rights Institute, 5,362 people have been arrested, hundreds have been tortured, and 2,381 have been hospitalized as a result of wounds from gunshots, pellets, and other weapons. Over two hundred people have been partially blinded by police pellet guns, and at least one young man, university student Gustavo Gatica, lost the sight in both his eyes due to shots from pellet guns. There are now 283 lawsuits against the police for torture, cruel treatment, and sexual violence.5 Piñera and his government will be accountable for the massive and brutal abuses perpetrated since October 18th by the army and the police.

The political and social crisis and general unrest has also led the Chilean government to cancel significant events, like the APEC meeting and COP25, as well as major soccer tournaments, musical concerts, and many other public events.

No one knows when and how this is going to end. However, Chile does not look the same as it did a month ago. While neoliberals continue to try to save the best part of the pie for themselves, demonstrators continue to occupy the streets of the main cities across the country. Something will emerge from the neoliberal wreckage, but the shape it will take is unknown.

Many questions are now being asked: How did long-term manipulation lead to the over-exploitation of millions of humble men and women? Who will deal with the huge social and economic debt the ruling classes now have with society? How will the elites give back the social and economic rights they practically confiscated from us?

In the meantime, the political elites and government have made some concessions by agreeing to freeze increases in subway fares, utilities, and highway tolls, and to increase pension payments for the poorest.

The government has also announced that there will be major constitutional transformations that will put an end to Pinochet’s constitution and call for a constituent assembly. Healthcare, medication, parliamentary expenses, and the exorbitantly high incomes of senators and deputies are also being targeted for reform. Without consultation or participation from the social realm, however, these agreements could receive support from the government but will be rejected by the largest social organizations, including unions, and environmental, student, indigenous, and women’s groups.

In 1970, Salvador Allende (1908-1973) inspired the world by promoting democratic socialism through an electoral process. He died resisting the coup d’état led by the armed forces and a coalition of right-wing political parties that took power on September 11th 1973. Once again, almost fifty years later, in a very different setting, the people of Chile may inspire the world in search of deep political transformation through mass and radical mobilization.

The people want peace but in the context of justice, freedom and democracy. In the meantime, thousands are taking to the streets on a daily basis to keep fighting for their demands and pushing back the neoliberal mantra. •

Chile Awakens: Some Thoughts on the Chilean Uprising

Oakland Socialist

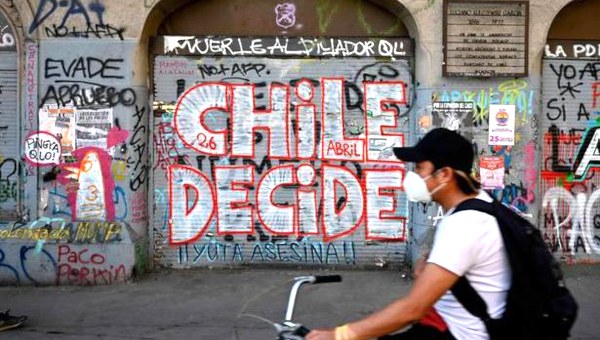

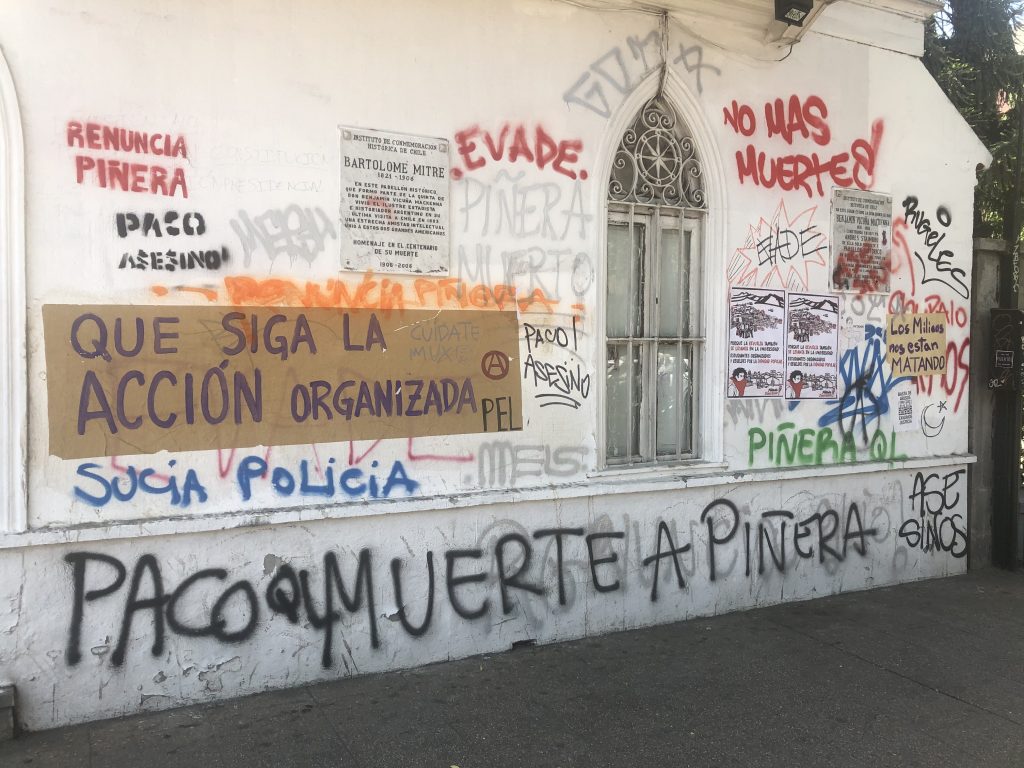

Everywhere you walk in the streets of Santiago, there is political graffiti spray painted on the buildings. A popular slogan among the graffiti is “Chile despertó” – Chile woke up. And truly, the whole society has awoken, with daily street protests and constant political discussions among all layers and all ages.

“Acuerdo”

After a month of daily protests, on Friday, November 15, Chile’s political parties agreed to organize a constitutional convention in order to rewrite the country’s constitution. The pact (“Acuerdo”) was called “Agreement for Social Peace and a New Constitution.” The agreement referred to the “the grave political and social crisis of the country,” and said that it’s purpose was to “the reestablishment of peace and public order.” That same evening, and every evening after, the crowds gathered, the stones flew at the “carabineros,” and tear gas filled the air. And the next evening, the carabineros murdered Abel Acuña. The following day, Sunday, normally a day of less protests, hundreds of bicycle riders(!) gathered at Santiago’s Plaza Italia – the central gathering place for the protests – in order to hold their own anti-government protest. Beatriz Sanchez, former candidate of the “Frente Amplio” (a coalition of several parties, including the Socialist Party) came down to express her support and to criticize the carabineros. She was greeted with chants of “y fueera! Y fueera!” – leave! Leave!

Pinochet/”Chicago Boys” Constitution

The background to this huge social and political crisis that is racking Chile is the constitution put in place by the Pinochet dictatorship before Pinochet left office in 1990. That constitution – a model for the neoliberal “Chicago Boys” – enshrines the privatization of nearly everything. Water is privatized, according to the constitution. So is healthcare, the national pension plan, the transport system – even the highways. And with this, a huge wealth gap has opened up. The exact same complaints that the youth in the US express are expressed by their counterparts in Chile – lack of jobs, student debt… everything.

The Mood

Every morning, as you walk by Plaza Italia, your eyes will water and your nose will sting. The tear gas from the night before lingers. So did the fear from the Pinochet years linger in the years that followed. But no longer. The youth have broken it. Not having lived through those years, they lacked that fear, and they have affected all the older generations. “Chile despertó” – Chile has awoken – is a popular wall slogan.

One worker in his late thirties or early forties explained that up until now, neighbors around where he lives wouldn’t talk to each other. Now, everybody is talking with everybody, he said, and they’re talking about politics.

The new patron saint of Chile appears to be “Matapaco” (cop killer). This refers to a black dog who had been living in the streets near some university and was popular with the students. For some reason, this dog (who recently died of natural causes) hated “paco” – the carabineros. One recent morning, a group of middle aged, nicely dressed women were in a restaurant celebrating the birthday of one of them. I was seated nearby and heard something like this: “blah, blah, blah… laughter… blah, blah, blah, laughter… Matapaco… blah, blah, blah.” Even at this celebration among these middle aged women, they were talking about Matapaco!

Literally for miles around Plaza Italia, the buildings are covered with political graffiti and posters. It is common for people to stop and read them. Getting into a conversation with those who are reading them is like walking up to an automatic door of some store. All you have to do is walk up into the electronic eye and the door opens. In Chile today, all you have to do is ask one of those reading those posters what they think and – boom! – you’re in a conversation whose length is only limited by how much time that person (or group of people) have to talk. It could be a 63 year-old woman selling crafts at a stand or a group of 18 or 20 year-old young women talking with this 73 year old man. It doesn’t matter. Everybody wants to talk.

Carabineros

The government appears to be divided in several ways:

First is the division between the elected wing and the carabineros, known pejoratively as “paco.” Organized at the national level, they are the only police force. There is no local or municipal police. And “paco” has a long history of brutality. In one instance, close to 100 years ago, they rounded up a group of some 100 or so workers who were organizing a union and killed them all. In another, they entered the class room of two college professors who were known to be members of the Communist Party and kidnapped these two professors. A couple of days later, the decapitated bodies of the professors were found by the roadside. As with any such force, the carabineros are also corrupt, with cases of the command faking payrolls to pocket the money and other such acts.

While the “Acuerdo” makes clear that the politicians are seeking to pacify the population by making concessions, the carabineros seem to be doing the opposite. One recent night at Plaza Italia, somebody threw a molotov cocktail at one of the “zorrillos,” which are kind of mini armored personnel carriers. The vehicle sped away with flames spreading on its hood. The rest of the police withdrew. After they left, the “protest” turned into a giant street party, with the young people singing, dancing and in general celebrating their public gathering. A half hour later, “paco” returned and the crowd was immediately transformed. The chants and cursing of the police (“Paco culiao” – more or less FTP in the US) returned and the rocks threw once again, as tear gas filled the air.

Everybody that this writer talked to agreed that the police actually want to agitate things so they can have an excuse to crack down. If they could, I believe the carabineros’ command structure would like to return to the “good old days” of Pinochet. But that is not possible at this time. According to one article, the approval rating for the government is at 9.8%. Nine point eight per cent! When Pinochet seized power, he more or less had the support of the Catholic hierarchy, which had an influence in Chilean society. Today, Catholicism is collapsing. In 2016, 70% of Chileans identified themselves as Catholic. In 2018 that figure was 58% and now it is down to 45%. Meanwhile, those who identify themselves as either atheist or having no religion has grown to 32% (from 21% in 2018).6

April Plebiscite

The Acuerdo, itself, calls for a plebiscite in April of 2020. That plebiscite will ask two questions: First is whether people want a new constitution. If the answer is “yes,” then the question is how a new constitution should be written. There are two choices: Either a “mixed” constitutional convention which would be half directly elected delegates and half present politicians; or a “constitutional convention” composed entirely of elected delegates. In either case, a two-thirds majority would be needed to approve a new constitution.

Already squabbles are breaking out between and even within the different political parties and some politicians are already questioning whether this agreement is workable or whether it will collapse. Meanwhile, different politicians regularly criticize the carabineros’ violations of human rights in general terms, but never raise the specific acts nor do they actually propose doing anything about it. In other words, the government is paralyzed.

View of Chileans

As for the movement from below – nobody seems to believe in the Acuerdo nor to trust the government.

The protests at Plaza Italia are every night. Starting around four in the afternoon, the youth start to gather. Then, around 5:00 or so Paco turns up and within an hour the tear gas flies. There doesn’t seem to be any formal organizing of these protests. People just spontaneously appear. There almost seems to be an anarchist mood among these youth, but they are not “anarchists.” For example, I have not seen the anarchist symbol anywhere among the graffiti.

Popular Assemblies

Another aspect is the weekly gatherings of the neighborhood “popular assemblies.” There are hundreds, probably thousands, of these that meet every Saturday afternoon. The one that I attended didn’t seem to have a formal, elected leadership. Rather, an agenda had been worked out by some group who simply had taken the ball and ran with it. That seemed to work out okay for the moment. This seems to be similar to how things worked in Occupy Oakland back in 2014. There, a small group of anarchists in effect decided the agenda and the general direction of the general assemblies. In that case, too, it worked out in the beginning. However, at a key moment, this small group of anarchists turned to the union bureaucracy and that turn meant that Occupy Oakland would not try to build a radical base within any sector of the working class, most especially not among union members.

Unions

Then there are the unions. While I was there, there was a teachers’ strike of sorts and a march and rally. They were joined by some students, and there was a very militant atmosphere. “Paco” was nowhere to be seen. At the ending rally, the speakers (in other words, the leadership) spoke in general terms. They talked about the need for a “decent wage,” but didn’t specify what that wage should be. They called for remembering those who had been wounded or killed by Paco, but didn’t say what should be done about Paco’s brutality. They called for “a constitutional convention that represents everybody in Chile.” One speaker even denounced “savage capitalism” and called for the construction of a “new society.” But what kind of society and how to construct it?

Next week, there is supposed to be a call for a several-day general strike. However, there was supposed to have been one on the day I arrived in Chile (November 14), but as far as I could see it didn’t happen. We will see what happens this time.

Future Possibilities

How can this situation be resolved? What might develop?

It seems to me that the carabineros are not under the complete control of the rest of the state. I could be wrong, but it doesn’t seem to be ruled out that they could initiate a new outrage on a major scale – maybe kill a dozen or more of the youth in one single event. Were they to do that, I think the result would be a general uprising and a near complete paralysis of the country, including a general strike. From there, who knows?

More likely is that the country staggers toward the April plebiscite. I am told that there is some sort of association of the country’s mayors and that in several of the local popular assemblies these mayors have some influence. Possibly something could be stitched up through them. The problem is that a 2/3 vote of whatever constitutional body that comes into being is needed for a new constitution – if the process even gets that far.

There is a general mood against all political parties. (One group of young women that I talked with, when I asked them what they thought of socialism, they responded, “sure, but not with any party.” They were referring to the Chilean Socialist Party.) The Communist Party has not signed the “Acuerdo,” but they really don’t offer any alternative either.

Overall, it seems that the hope of the government is that over time, a large enough sector of the working class will tire of the protests. Among other things, the unstable situation is having an effect on the economy as is the world market.

To sum up: There seems to be a semi-paralysis as well as serious divisions at the top. After over a month, the protests don’t seem to be fading and the popular assemblies seem to be continuing. The main issue driving this is that of privatization of nearly everything and the huge wealth gap that results. But those at the top are not going to surrender their position. What will be required is an organized movement from below. How the existing massive movement can be organized is the question of the hour.

Some Thoughts on Program

The newspapers are full of comments from various politicians saying that a lot will have to change in Chile, but it cannot change immediately. Sure enough, on November 20 the government decided that there will be an immediate 50% increase in pension payments… for all those pensioners over 80 years old! It seems to me that there could be demands for a specific raise for all pensioners, plus not just a “decent” minimum wage, but for a minimum wage of a specified amount.

The event that sparked off the first protests was an increase in the cost of riding the metro. It seems to me that there could be a demand for free public transport.

Also, abortion is severely restricted and there are numerous wall signs calling for free abortion on demand.

Finally, and of critical importance, it seems to me that a demand could be raised to disband the hated carabineros. In its place, the popular assemblies should be provided with the funds previously spent on the carabineros and they can provide for security, direct traffic, etc.

I suspect that this last demand would be quite popular among the youth who are out protesting every evening, and maybe meetings could be organized near or at Plaza Italia to discuss this demand.

As I understand it, these youth don’t participate in the popular assemblies, but maybe they would be willing to bring this demand to those assemblies and try to get the assemblies to adopt them.

Personal Report

I spent a lot of time in Santiago just walking the streets, looking around and getting into conversations with people as well as at the daily protests at Plaza Italia and a few marches and union events. I have already written up reports on my blog.

Also, before I left for Chile, I contacted several socialist groups there to try to meet up. The only one that responded was the MST (Socialist Workers Movement), which is part of a Trotskyist international grouping called the UIT. I spent quite a bit of time with these comrades. I found that time to be very helpful (and enjoyable), and I thank those comrades.

Some Questions

I was also left with a few questions. Some of them are raised above regarding program.

As with the socialist left here in the US, I think that one main focus of attention has to be analyzing the views and positions of different elements of the ruling class and the conflicts within that class and their government. Yes, we must pay attention to the struggle between the working class and the ruling class, but that is only part of the issue. Without the former, it’s impossible to really develop a sense of where things are moving, and without that, the working class movement can in the main just respond to events rather than anticipate and start to control them. Or, put another way, it’s by taking a bird’s eye view of society that the working class can start to see itself as the class that can and should rule.

Being new to Chile and having been there for only slightly over a week, it is impossible for me to have a clear idea of the way forward. One main issue is how can the popular assemblies be developed further? Is it possible for them to make links with unions? Maybe such links already exist to some degree or another. If so, how can that be formalized?

Also, the apparently very open and informal way in which at least some of the popular assemblies are organized may have some advantages for the moment, but it seems to me that there is a danger that that same informality can be used in the future as it was used in Occupy Oakland. So the question is how can the idea of building a formal democratically elected leadership be introduced?

Conclusion

You could throw a dart at a map of the world, and likely as not you’d hit a country that was in crisis and turmoil, a country where mass uprising was underway – Iraq, Lebanon, Iran, Sudan, Tunisia, Haiti, Colombia… In Bolivia, matters are far from settled. How will these movements come together? What will be the next stage in the growing world revolt against the ravages of capitalism? How will the world working class start to stamp its imprint and build its own world working class party? •

This article first published on the Oakland Socialist website. Also available in Spanish at “Chile Despertó: Algunas reflexiones sobre el levantamiento chileno.”

Endnotes

- In March 1975, Milton Friedman and Arnold Harbenger flew to Santiago. Friedman was greeted as a rock star. He called for “shock treatment. That is the only medicine. Absolutely. There is no other long-term solution!” He urged Pinochet to cut government spending much further, by 25% within 6 months: people would soon get new jobs in the privatized companies. Perhaps shock treatment was never about jolting an economy into health. Perhaps it was meant to do what it did: hoover wealth up to the top and shock much of the middle class out of existence.

- On War by Carl von Clausewitz. “War is nothing but a continuation of politics with the admixture of other means.”

- General Augusto Pinochet and his supporters called the September 11 Chilean coup in 1973 a ‘war‘, and it certainly looked like one: tanks fired as they rolled down the boulevards and government buildings were under fire from fighter jets. But this war had only one side.

- Capitalism internalizes cannibalistic as well as predatory and fraudulent practices. But it is, as Luxemburg cogently observed, ‘often hard to determine, within the tangle of violence and contests of power, the stern laws of the economic process.’ Accumulation by dispossession can occur in a variety of ways and there is much that is both contingent and haphazard about its modus operandi. (David Harvey. “The ‘New’ Imperialism: Accumulation by Dispossession”).

- These sums are changing on a daily basis, since mobilizations do not halt after five weeks of intense demonstrations from across the country.

- El Mercurio newspaper, 11/22/2019.