Ontario’s Resource Revenue Sharing Agreements

A Step Toward Reconciliation?

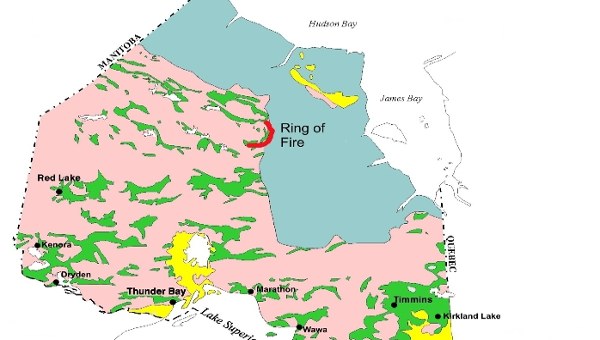

Announced last spring, Ontario’s new resource revenue sharing (RRS) agreements with three northern First Nations councils are set to come into effect this fall. The agreements were marketed with lofty rhetoric. The government press release described them as “an historic step on Ontario’s journey of healing and reconciliation with Indigenous peoples.”

The MacDonald Laurier Institute’s Senior Munk Fellow Ken Coates partnered with IAMGOLD Corporation’s Stephen Crozier in penning a glowing editorial in the Globe and Mail, calling RRS a “transformative development” that would change “the very foundations of resource development in Ontario.” Coates and Crozier praised the agreements for their simplicity, noting the details were “straightforward.” Under RRS, the province will allocate 45 per cent of forestry stumpage fees as well as 40 per cent of mining tax payments associated with active mines to participating First Nations, “with no strings attached.”

In many respects, RRS appears to meet the longstanding demands of Indigenous peoples and their allies, who have been pressing the government for a more equitable distribution of the province’s mineral wealth for the better part of a decade.

Yet, RRS is hardly about “healing” or “reconciliation.” Instead, RRS is consistent with the Ontario government’s longstanding policy of opening up as much public land to private mineral extraction as it can. The real goal of RRS is to lock First Nations into precisely the type of extractivist development model that has defined Ontario’s Northern development strategy for decades.

Taxes and Loopholes

The problem is obvious to anyone familiar with Ontario’s mining tax, which serves as the province’s royalty for the use of the public’s non-renewable resources. The mining tax is so riddled with loopholes, exemptions and deductions that, oftentimes, even the most profitable companies pay no tax at all.

Take Glencore, for example. Glencore is the world’s biggest commodities trader, with a huge stake in everything from soybeans to base metals to thermal coal. With operations spanning six continents, Glencore controls assets worth $129-billion. In 2018, the company reported sales revenues of just under $220-billion, good for 16th place among the world’s largest publicly-traded corporations. Recently, Glencore made a splash when it announced that it would “improve transparency” and cut down on its use of offshore tax havens.

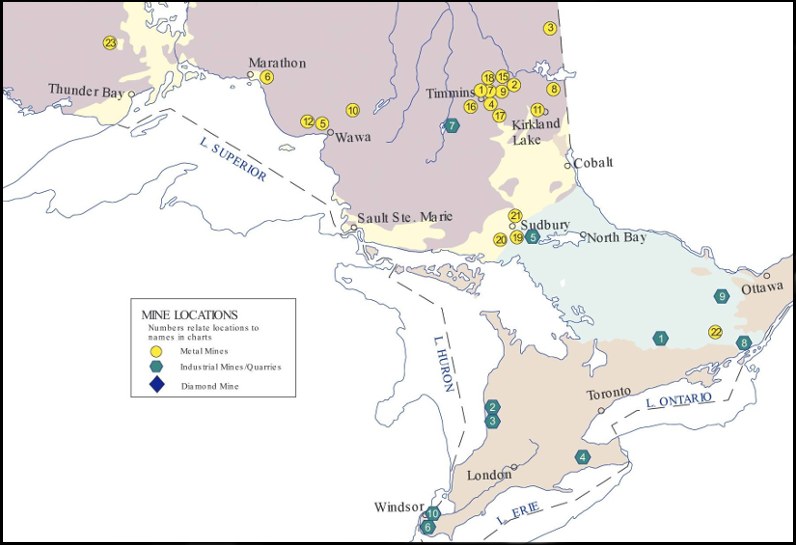

Yet, the company is notably opaque when it comes to its Ontario operations. There is no way for the public to know how much revenue the company earns from its three mines in the province. Its annual reports lump together its Sudbury-area nickel operations with its other “nickel assets” in Quebec and Norway forming its “Integrated Nickel Operations.” Similarly, its Kidd Creek copper-zinc mine near Timmins is but one piece of the company’s much larger “North America zinc assets,” which include the Bracemac-McLeod mine in Matagami Quebec, the CEZ Refinery in Valleyfield, Quebec and the Brunswick Lead Smelter in Belledune, New Brunswick.

Together, Glencore’s Integrated Nickel Operations and North America zinc assets generated $3.9-billion in 2018. Meanwhile, Glencore’s taxes on income paid to the Ontario government totalled just $14.4-million – an amount equivalent to less than half of one per cent of its Canadian-based nickel and zinc revenues. The year prior, Glencore paid no tax to Ontario.

Glencore is exceptional only for its massive size. Other mining companies receive similarly generous tax treatment. For instance, Detour Gold, controlled by Wall Street hedge-fund billionaire John Paulson, paid no tax to either the federal or provincial governments in the three-year period 2016-2018. Over that time, the company extracted more than $2.1-billion worth of gold from its single mine in the Detour Lake area.

Risky Taxes

How do companies earning such huge revenues pay such minuscule taxes? To answer that, we have to look at the structure of Ontario’s mining tax. Since its inception in the early twentieth century, the primary objective of the mining tax hasn’t been to collect revenues, but to promote mining investment. The tax structure itself is based on two tenuous assumptions. First, that mining is an especially “risky” business that deserves special tax treatment. And second, that mining generates an array of spin-off benefits that drive regional economic development in the provincial north. The fact that neither assumption is true – several studies have shown that mineral extraction is no riskier than other business ventures and that most of mining’s “spin-off” benefits are concentrated in urban centres far from where extraction takes place – hasn’t prevented generations of policymakers from reverting to precisely the same arguments.

The first thing to know about the mining tax is that, unlike a traditional ad valorem royalty, it is a tax on net profits, not on revenues. Only companies that show a book profit (for tax purposes) above $500,000 are subject to the tax. Companies that don’t show a profit aren’t. In cases where companies don’t show a profit, the public receives no return for the depletion of its non-renewable resources, and the companies receive their raw materials free of charge.

Another thing to know is that it is a tax on profits from mineral extraction only. That is, the mining tax does not apply to profits earned from mineral processing. The problem with this is that most mining companies do their own processing, so it’s impossible to know what portion of their profits comes from extraction and what portion comes from processing. As a result, the government has devised an arbitrary formula called the processing allowance that assigns a given percentage of a company’s total profits to mining and a given percentage to processing.

The industry has fought hard to make sure that the formula used assigns as much to processing as it can. For instance, while mining companies have every incentive to locate their smelters close to their mines to lower their shipping costs, Ontario provides a more generous processing allowance to companies that have their smelters in Canada than those that don’t.

The industry enjoys several other special concessions that lessens its tax burden. New mines, or mines that have undergone a “major expansion” are exempt from the mining tax for the first three years of their operation. For so-called “remote mines” in the “Far North,” the exemption extends to ten years.

Exploration and development expenditures, that is, the costs associated with finding mineral deposits and constructing new mines, are 100 per cent deductible at the discretion of the company. These costs can be pooled together and carried forward indefinitely so as to regulate future tax payments. In low-profit years, they can be saved. In high-profit years, they can be used to lower taxable income.

Notably, mine operators are also allowed to deduct donations made for charitable and educational purposes related to mining. In other words, the industry’s propaganda is publicly subsidized.

Given the structure of the mining tax, the obvious question becomes: If a company pays no mining tax, how much revenue can a signatory First Nation expect to receive in return? After all, 40 per cent of 0 is 0! Further compounding the problem, company and mine-specific mining tax payments are confidential under the Mining Tax Act.

It turns out, RRS won’t be based off company-specific mining tax payments at all. As a Senior Policy Advisor from the Minister of Energy, Northern Development and Mines explained by email, “specific mining tax and royalty data for each mine in the province is not available on a per company or per mine basis and is not being used to calculate the Mining Funds in the resource revenue sharing agreements.”

Instead, “Ontario has negotiated agreements that use a formula that assigns a notional allocation to each active mine.”

The notional allocation will be calculated using “publicly available information including gross revenues from all mining operations in Ontario and Ontario mining tax and royalty revenue as published in Ontario’s Public Accounts.”

If the details of this arrangement are hardly as clear as its proponents have made it out to be, its benefits to industry are. At no additional cost to themselves, mining companies have locked signatory First Nations into an economic development model that clearly favours enhanced mineral extraction. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the industry itself has advocated a form of revenue sharing, on condition that it be derived from existing tax payments. As Ontario Mining Association President Chris Hodgson explained to Sudbury Mining Solutions Journal, “We advocated for revenue sharing for a long time to try to align the interests between local communities and the Indigenous communities and the mining community. [RRS] aligns interests even further. You get paid when you have an actual mine in production.”

Given the structure of the agreements, even those companies that pay no mining tax will benefit from the goodwill generated by the funding allocations.

First Nations Communities

The implications for First Nations communities are clear. With RRS bringing in revenues to pay for much-needed programs and services in social welfare, education and health, First Nations will have to think hard about government policies that could reduce industry profits. And since new mines will come with an even higher allocation of 45 per cent of their “mining tax payments,” signatory First Nations now have a strong incentive to welcome mineral exploration on their traditional territories.

Already there are indications that RRS is contributing to this type of thinking. As Wabun Tribal Council’s mineral development advisor Stephanie Labelle recently wrote in the Canadian Mining Journal, RRS “is built on the sharing of a profit-based tax, which should incentivize First Nations to work meaningfully with mining companies with the success and development of existing and prospective projects.”

RRS is hardly the transformative development its boosters have made it out to be. In “aligning the interests” of First Nations communities with the interests of the mining industry, it is but one of a long line of measures the province has taken to facilitate the private accumulation of mineral wealth in the provincial north. •

A shorter version of this article was initially published on the Ontarians for a Just Accountable Mineral Strategy website.