We All Live in a Mediocracy

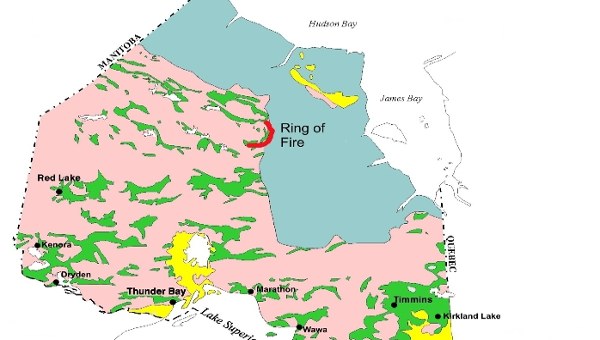

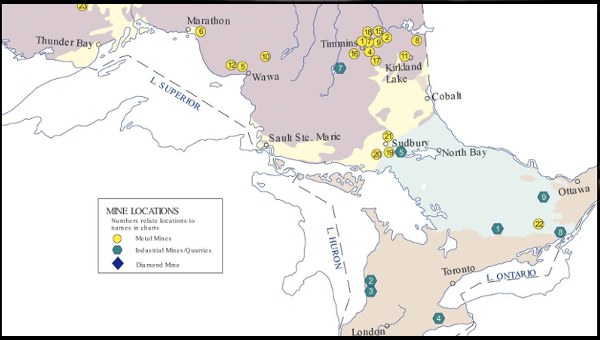

Alain Deneault has become one of the most important Canadian public intellectuals Anglosphere audiences have never heard of. Having completed a doctorate on the economic thought of German social theorist Georg Simmel under the supervision of Jacques Rancière at Université Paris VIII, Deneault returned to Canada and promptly published a number of works notable for demonstrating the Canadian state’s links to the global mining sector on the one hand, and Canada’s involvement in the spread and use of tax havens worldwide on the other. Since that time, Deneault has become one of the country’s foremost experts on these topics, frequently appearing in French language media in both Canada and abroad, having recently offered commentary on the Paradise Papers’ revelations of systematic globalized tax sheltering by the world’s political and economic elites. Bold writing on such topics has also placed Deneault at the centre of controversy in Canada.

Most controversial among such works was Noir Canada, co-written with Delphine Abadie and William Sacher, published by Montreal based Écosociété in 2008. This book, written in French and sold primarily in Quebec, outlined the operations of Canadian mining entities working in Africa. So controversial were the book’s claims that it ultimately led to Deneault and his coauthors to be at the centre of two multi million-dollar SLAPP (strategic lawsuit against public participation) cases, one brought forward by Barrick Gold in Quebec, and the other by Banro Corporation in Ontario. What ensued were some of Canada’s most important freedom of expression cases, leading to the passing in Quebec of an Act to Amend the Code of Civil Procedure to Prevent Improper Use of the Courts and Promote Freedom of Expression and Citizen Participation in Public Debate. The cases and events surrounding the litigation were also the subject of a National Film Board of Canada documentary, “Silence is Gold.”1 Deneault and his co-authors ultimately settled out of court, agreeing to withdraw Noir Canada from publication. Consequently, two books offering a modified presentation of similar material were later published.2

Most controversial among such works was Noir Canada, co-written with Delphine Abadie and William Sacher, published by Montreal based Écosociété in 2008. This book, written in French and sold primarily in Quebec, outlined the operations of Canadian mining entities working in Africa. So controversial were the book’s claims that it ultimately led to Deneault and his coauthors to be at the centre of two multi million-dollar SLAPP (strategic lawsuit against public participation) cases, one brought forward by Barrick Gold in Quebec, and the other by Banro Corporation in Ontario. What ensued were some of Canada’s most important freedom of expression cases, leading to the passing in Quebec of an Act to Amend the Code of Civil Procedure to Prevent Improper Use of the Courts and Promote Freedom of Expression and Citizen Participation in Public Debate. The cases and events surrounding the litigation were also the subject of a National Film Board of Canada documentary, “Silence is Gold.”1 Deneault and his co-authors ultimately settled out of court, agreeing to withdraw Noir Canada from publication. Consequently, two books offering a modified presentation of similar material were later published.2

Blessed Are the Mediocre,

For They Shall Inherit the Earth

Deneault’s resilience in the face of the two SLAPP cases surely stands as one the major examples in Canadian history of an intellectual speaking truth to power. And while Deneault has continued to publish works focusing on Canadian mining companies and Canada’s implication in tax havens, his most recent works draw out, with a popular sensibility, the generalized philosophical, social and political implications of his empirical studies. Works like Faire l’économie de la haine – Douze essais pour une pensée critique (2012), Gouvernance: le management totalitaire (2013), Le Totalitarisme pervers: d’une multinationale au pouvoir (2017) are of a more literary character, never hesitating to cite Mallarmé, Flaubert or Camus alongside Weber, Marx or Durkheim. It is within this latter, almost polemical form – the French essai – that Mediocracy: The Politics of the Extreme Centre is situated.

First appearing in French as La Médiocratie in 2015, this English translation by Catherine Browne appears in a slightly adapted version from the original French. Longer paragraphs are broken up; some idioms are modestly anglicized. Most importantly, an epilogue sourced from excerpts of Deneault’s other writings is added to the text. Regrettably, the separate references and bibliography section included in the French edition is omitted here in favour of all inclusive end notes.

While readers should be aware of these modest alterations, they do not detract from the argument of Mediocracy even if they serve to render a somewhat different product from the original. To this end, Deneault’s argument in Mediocracy is pointedly blunt: “mediocracy, therefore, is the average when it has been granted authority” (p. 2). From here on, Deneault’s writing unfolds by way of a series of thematically related anecdotes taken from a variety of social fields; knowledge production, the economy, arts, and politics.

At its most stark, Deneault’s approach leads readers to consider the horror of really-existing mediocracy. Most troubling in this respect is Deneault’s identification of the banality at the core of the political response to the 2013 Lac Mégantic disaster. In the aftermath of a train full of crude oil exploding in the small Quebec town’s city centre, killing 47 people and resulting in millions of dollars in damages, artists were summoned to soothe the utterly devastated local population. The absurdity of it all is palpable as Deneault writes, “Lac Mégantic was now something you might read about in People magazine. Suddenly, the story was no longer political: it was about feeling the right feelings” (p. 125). The “Artist as Social Worker,” as Deneault puts it, serves to obscure the fact that the Lac Mégantic disaster could easily have been avoided had it not been for mediocratic government regulation, “[Lac Mégantic] was a disaster waiting to happen… Transport Canada had granted the Montreal, Maine, and Atlantic Railway special permission to assign a single engineer to its trains. Was this due to lobbying? corruption? The Quebec government was certainly aware of this transportation activity but never opposed it” (p. 124).

For Deneault, examples like the Lac Mégantic disaster serve to demonstrate the callous indifference of mediocratic regimes. Yet, mediocracy is not just evident in such meek responses to extreme events. As a regime, mediocracy extends to all spheres of society; “it describes not so much domination of mediocre people as the state of domination created by mediocre forms themselves… as the currency of meaning and sometimes the key to survival” (p. 10). We thus read of academics induced to sell out, spineless politicians, ritualized and inconsequential post-modern art, a dilletante millionaire and billionaire class – no one is spared from the injunction to be mediocre.

Make no mistake however, despite its critical bite, Deneault’s politics are most fruitfully understood within the lineage of a critically minded left republicanism, sympathetic to, but not always in full agreement with, Marxism. Deneault is nevertheless vitally concerned with a robust definition and defence of the public good. He writes, “these plebeian worlds, rich in ideas and initiatives… can also develop as places of utter confusion where people reinvent hot water, establish new ‘social contracts’ with all the flaws of the old ones, and carry out the violence of original foundational acts in a manner not unlike certain totalitarian regimes, albeit on a much smaller scale” (p. 137). While not necessarily Marxist then, neither is Deneault an anarchist proselytizing for localism.

What is thus at stake for Deneault is the corruption of the public sphere and the related intermediate spaces of civil society. “Citizenship,” writes Deneault, “is now understood as an aggregate of people advocating for private interests in the manner of small lobbyists” (p. 141), “Let us therefore view the democratic principle as corrupted” (p. 140). It is ultimately here where the perversity of mediocracy lies – one must be individually mediocre to survive, but this kind of survivalist mediocrity stakes the overall survival of society since it increasingly comes at the cost of the erosion of the public sphere on which we all depend.

The Limits of Deneault’s Mediocrity

At first glance, many will no doubt find some overlap in Deneault’s chosen themes with the academically derived work of the Frankfurt School and related thinkers such as Mark Fisher (Capitalist Realism: Is There no Alternative?). Readers, while correct to make such an assumption, should nevertheless endeavour not to allow the pleasingly dour tone of Deneault’s writing confirm them in this prejudice. Likewise, those less familiar with the latter but aware of more popularly pitched works by writers like Chris Hedges (Death of the Liberal Class), Thomas Frank (Listen, Liberal: Or Whatever Happened to the Party of the People?) or Tariq Ali (The Extreme Centre: A Warning) may also be wondering what specifically sets apart Deneault’s Mediocracy.

In a sense, one could think of Deneault as splitting the difference between the two above poles. Though flirting with the high theory of the Frankfurt school on the one hand, Deneault always tames his recourse to ensure real world examples are offered in a way that allows the theory to insightfully illuminate the case at hand. This is not to say that Mediocracy is a work of pop-theory: Deneault’s appeals to real world examples are frequent enough, detailed enough, and varied enough that the merits of his argument can be confidently assessed without reaching for the Penguin Dictionary of Critical Theory.

What this means is that, for initiates of the Frankfurt School, Deneault does not elaborate a truly satisfying theory of mediocratic regimes. This is too bad since the idea is itself so interesting, Deneault would be welcome to further elaborate it as many questions suggested by the notion are effectively left open ended. Likewise, those looking for a full exposition of the worst cases of mediocratic corruption may also be found wanting – a thorough study of a single such case is just not suited for the kind of popular intervention on offer here.

This is nevertheless a book that should be read. Deneault’s frequent, though not exclusive, reference to Canadian examples is refreshing and both Canadian, and international audiences alike will appreciate the book’s ability to temper the official political narrative coming from Ottawa today. Canada is not, nor has it ever been, an unspoiled land of milk and honey. We are so ceaselessly inundated with such fanciful messages that the perspective Deneault offers in Mediocracy facilitates a critical discernment of our current public discourse in Canada and abroad. An obvious example in this respect is Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s pronouncement that ‘Canada is back’. While the comment was intended to signal a turn toward to the kind of robust multilateralism many Canadians aspire to, it is increasingly acknowledged that the differences between Justin Trudeau’s Liberals and Stephen Harper’s Conservatives are much more an exercise in style over substance.3 Such tendencies would seem to, unfortunately, confirm Deneault’s analysis.

As Deneault argues however, this does not mean that those who purvey such thought or politics are fundamentally lazy, or undeserving of their status in society. Recall that mediocracy as a regime compels mediocrity as a form of self-preservation. Rather, Deneault quite correctly encourages us to resist the temptation to mediocrity by considering the ultimate form and manner in which our public deliberations take place, “whenever an attitude frees us from the harmful ways of mediocrity, whenever an idea helps us develop a justly instituted public life, these will be ways for us to move forward, without any guarantees” (p. 138).

Those on the left in English speaking Canada and beyond take note, only the mediocre are compelled not to heed Deneault’s call. One could do worse than – and many would likely benefit from – raising the issues Deneault has put forth in Mediocracy within their own circles. An elitism for the people, anyone? •

Endnotes

- The documentary is available to be viewed in its entirety on the NFB website.

- “Alain Deneault in Conversation with Canadian Dimension.”

- Konrad Yakabuski, “Canada’s Back, when it’s Convenient,” Globe and Mail, April 6, 2018.