After Carillion: The Struggle to Democratize Social Services

Carillion’s failure has been compared to the collapse of Lehman Brothers in 2008, but what the Lehman case shows is that you can engage in behaviour that puts millions out of work, and destroys the hopes of a generation, and not pay any price, or significantly change your behaviour. Lehman was emphatically not a ‘watershed’: no one has paid a significant price for the greed, irresponsibility and criminal behaviour that was exposed when Lehman went bust. The challenge is to ensure that the Carillion moment will be different: that the ideology that has led to companies like Carillion fleecing the public and jeopardizing livelihoods finally gives way to a new common sense about how Britain must be run.

The collapse of Lehman Brothers showed that financial capital was out of control and had gambled with the livelihoods of everyone in the world – and lost. What has the collapse of Carillion shown? It has certainly shown up the dangers and fallacies of outsourcing, and of the use of private finance initiative (PFI) for public infrastructure: the unbelievable greed of today’s company directors, and their often almost equally unbelievable incompetence; the incapacity, or reluctance, of the government and other public bodies to enforce the fulfillment of contracts, especially when it will show how irresponsible the government was to entrust essential services to any private company; the conflict of interest of corporate auditors, and their consequent complicity in corporate wrongdoing; the fact that risk remains in reality with the public, even though a large element in the cost of contracts is to allow the private provider to insure against risk; and so on.

But these are not the issues we should be focusing on if Carillion is to become a watershed. They can be dealt with by piecemeal reforms. After Carillion no one – perhaps not even Theresa May’s perilously weak government – will be keen to propose new PFI infrastructure projects; and even defenders of public service outsourcing agree (perhaps belatedly) that it needs to be drastically curtailed: it should only be done, they now say, if “there is a market in the service [i.e. there are enough providers competing to provide it]; the difference between good and bad performance can be measured; and the service isn’t integral to the purpose and reputation of government.”

Neoliberal Myths

And the Labour Party is joining in this sort of discussion, proposing that outsourcing of services should only occur if a public service has ‘failed’, and only after public consultations. But this buys into the world view of neoliberalism and its myths and dogmas. It was not because hospital catering services were failing that Margaret Thatcher forced the NHS to outsource them, and while privatizing them may have made them cheaper it has not made them better; and how many people still think public consultations are anything but formal rituals before the implementation of decisions already made?

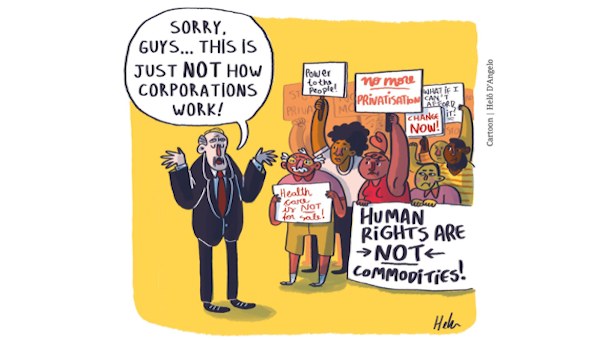

More seriously, this response implies a future in which we will still be contemplating privatizing public services, rather than resourcing them adequately, and making them democratically accountable. It misses the point about Carillion, and the opportunity: instead of making Carillion a watershed moment, debating it on this level means getting bogged down in arguments within the existing framework of neoliberal thinking.

The Carillion debacle needs instead to be seen not in its details but in its essence, as yet another predictable product of an entire, discredited political project that we must unambiguously move beyond. Not just outsourcing, not just PFI, but the whole doctrine of ‘the market knows best’, of the downsized state, of allowing only corporations to plan, of abandoning the boundary between the civil service and the private sector. Yet – and this is still more important – even a categorical rejection of all that will not make Carillion a watershed moment. People will not abandon the existing policy regime simply because it leads to even such massive disasters as Carillion (and the collapse of the care home provider Southern Cross, the PIP, Libor, and foreign exchange scandals and so many other failures and crimes). Our lives are now so intimately attuned to the neoliberal model that unless we are directly injured by its failures we are liable to shrug fatalistically – unless something clearly better is on offer.

Democratizing the State

That something else can only be a rebuilt, democratized state. Rebuilding the state means not only restoring its capacity to plan, which has itself been outsourced (to management consultancies and corporate-funded think tanks), but also its capacity to provide public services. And it means rebuilding not only central government, but also local government, and giving it significant resources and autonomy.

This will require more revenue. We are now among the lowest tax jurisdictions in the EU; UK tax revenues are just 33% of GDP, compared with 40-45% in Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Italy, Norway, and Sweden (Germany and the Netherlands are 38 and 39% respectively). No wonder the performance of the UK state is a litany of failures. A state capable of reorganizing the UK economy, protecting people from damage by market forces and empowering them to rebuild wrecked communities, will cost money. Market forces do not produce decent societies. Decent societies can only be created by governments with serious resources and strong public support.

And strong public support can only be earned by democratizing the state. No one now seriously pretends that the UK state is democratic. There is strikingly wide agreement that this very fact has led to Brexit: people seized the only chance they felt they had ever had to actually influence policy, however much the result is likely to be yet another disaster. What replaces the defunct neoliberal model must above all rest on new forms of democratic input and accountability at every level of government.

All this doesn’t mean saying little or nothing about Carillion itself, but what is said needs linking to the new progressive project for government that Labour has to develop, and could even do some immediate good. For example the National Audit Office (NAO) has just pointed out that the cost of buying out existing PFI contracts would be prohibitive. But Labour could make it clear that under a Labour government corporate shareholders in existing PFI projects would get no further government contracts of any kind unless they were willing to renegotiate the existing contracts to make them less unfavourable to the public. As a study from the Centre for Health and the Public Interest notes, just eight companies have major equity stakes in 92% of all 125 NHS PFI projects: in other words, there are companies a large part of whose business is in public sector contracts. Serving notice that they will not have a future in this business unless they are willing to give up drawing excessive profits from it now might well lead to a change of attitude to renegotiation.

Labour could also make it clear that with some exceptions, such as in relation to national security, under Labour public service contracts will be published in full, and that providers will be subject to the Freedom of Information Act in respect of all aspects of their performance of the contract – i.e. they will be treated like public providers of public services. This sounds simple, but it is largely the lack of transparency and accountability that has made outsourcing profitable, at the expense of service quality and the pay and conditions of employees. When this immunity is removed, the alleged efficiencies of private provision are likely to look much less plausible.

But while such specifics might help clear a small path for the new, progressive governmental project that is needed, the work of fleshing it out has hardly begun. If Carillion is to become a historic watershed this is the urgent task. •

This article first published by Red Pepper magazine.