Anti-Privatization Movements in the Global South: P3s and Women's Human Rights

On March 29, 2021, we caught up with Corina Rodriguez Enriquez and Masaya Llavaneras Blanco, researchers with Development Alternatives with Women for a New Era (DAWN) “a network of feminist scholars, researchers and activists from the economic South working for economic and gender justice and sustainable and democratic development.” DAWN’s recent report details the impact of various public-private partnership (PPPs) on women in countries around the world, such as Ghana, Peru, Fiji, India, Sierra Leone, and Zimbabwe.

In addition to their work with DAWN, Corina is the Academic Director and Principal Researcher at the Centro Interdisciplinario para el Estudio de Políticas Públicas (CIEPP) in Argentina. Masaya is also an Assistant Professor of Development Studies at Huron University College at University of Western Ontario.

This interview is part of a series with the Blended Finance Project a group of unions, non-governmental organizations, and academics who are concerned about the Canadian government’s embrace of what is called “blended finance.” We argue that blended finance is merely the latest iteration of the privatization and financialization of foreign aid and seek to engage others in Canada and around the world to propose more equitable public alternatives. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Adrian Murray (AM), Susan Spronk (SS): The Blended Finance Project seeks to critique some of the broader impacts of shifts toward attracting private sector development investments. How do PPPs or public-private partnerships fit into these broader processes and shifts in global development governance?

Corina Rodriguez Enriquez (CRE): We locate PPPs within a broader process – where blended finance also fits – that we call “corporate capture.” This includes corporate capture of the state but also of global governments.

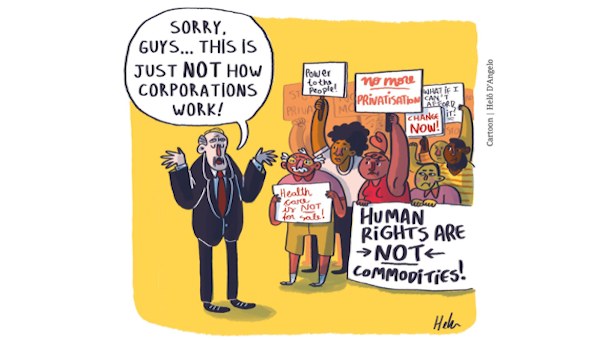

For decades, there has been a race to the bottom in fiscal and tax standards. Corporations are willing to pay less and less taxes. They dodge taxes all the time. There is also a flow of illicit financial flows. So, states, because they receive less tax revenue, face fiscal crises, and then feel forced to implement austerity policies. And because of austerity, states are not able to keep up the investments in infrastructure needed for development. It is a cyclical process: corporations refuse to pay taxes but then present themselves as the only ones that supposedly have the money to pay for much-needed infrastructure. The narrative that supports this process also privileges the private sector: “whatever is good for corporations is good for citizens and for all of us.”

Public-private partnerships are not new, but we see a renewed push in the current moment because, one, they open new business opportunities for the private sector, specifically in those sectors where public provisioning was formerly the rule. Second, it’s a way of sharing risk between the private sector and the public sector, pushing the risk onto the latter.

The deepest impact is that PPPs shift development priorities. Under the PPP model, investment is not oriented to people’s needs but mainly to private sector willingness to gain more profit. This means a shift in priorities because while there might be projects that might not be so profitable but very much necessary in terms of what people need, these are not funded. As such, this orientation toward profit limits the public policy space.

Then there is a more concrete impact on people who live in the Global South. PPPs are more expensive than public provision. The private sector needs to profit. And many times, in order to guarantee this profit, PPPs limit access to services to only those who can afford to pay.

PPPs also fuel a process of poor transparency and accountability, which is something that we already deal with in the Global South with our governments not being accountable enough. I think these PPP projects really fit into that because the negotiations are very obscure, the contracts are often secret, and citizens cannot access the information and cannot monitor the decision-making process or the delivery.

AM, SS: One of the things that we talk a lot about with respect to PPPs is “risk.” What do you think are some of the risks of orienting development investment toward “bankable” or profitable projects? Who bears the brunt of this “risk”?

CRE: The basic risk is that citizens are unable to monitor what’s going on. It starts from the very beginning of the PPP process because negotiations are carried out behind closed doors. In Argentina, for example, even when we citizens have the right to access information, it is denied! This lack of transparency has major implications because contracts are often changed along the way; and they are always changed in favour of the private sector. There is no way that citizens can monitor these developments. Information is power. So, if people don’t have information about what’s going on, then they cannot complain. This is true in the South but also in the North.

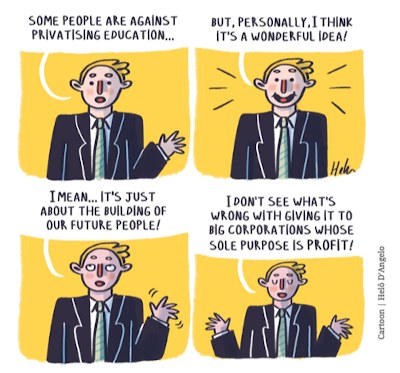

Masaya Llavaneras Blanco (MLB): I think the idea of rendering development into a business niche of sorts creates a very wrong set of incentives in terms of policy. It misplaces the focus from well-being and development to profit-making. This idea that development has to produce a profit limits the capacity for the provision of effective, fair, equitable services. This is very clear in public services such as water and energy, and it’s also very clear in terms of health and education.

Health and education are not sectors that are meant to produce profit or gains in a dollar value in immediate ways. But we know they produce societal gains that are necessary in the long term. But if our set of incentives for creating policy is focused on the immediacy of a dollar value for a particular corporation, we are going to produce poor societal results. We are sacrificing the rights of people in the name of the allure of ‘efficiency.’ When we analyze what is happening on the ground, however, that is not what we see. What we see instead are serious delays, opaque practices, and the erosion of human rights. So, PPPs are a bad deal altogether.

It is important that we mention the advocates and researchers throughout the global South we wrote our report with. The information we are sharing with you has been collected collectively. Two cases that come to mind in terms of lack of transparency are hospitals in Fiji and Peru.

In the case of Fiji, one of the first PPPs in the country entailed the renovation of a hospital and the construction of a new one. Nobody was consulted; it is unclear what the hospitals will be dealing with, what kind of specialties, who will be the beneficiaries of these hospitals. The project raises concern due to the potential creation of health tourism as a new source of income for a country that is already heavily dependent on tourism. So, this idea of development as a business niche perpetuates relationships of dependency that are already vicious and are likely to be deepened through privatization.

Another case where lack of transparency is also clear is in the case of Peru in one large hospital. Where again, even though the contracts were available, all the background information, so all the reports that sustained decisions to go forward with the contracts, are not available to the population. And this is not only the general public who are not aware of this issue, but nurses, medical doctors, people who have this specialty to actually look at this information and have informed judgment, they are not consulted, and they are not even having access to this. So, the opacity is widespread, which is often in contrast to what they say the public-private partnerships would be. They’re often, you know, portrayed as a form of increased transparency, but we have seen the opposite in all ten cases that we researched.

AM, SS: How do you think PPPs impact the supposed beneficiaries of development programs, but particularly, girls and women, which is the focus of your recent report?

MLB: In the case of beneficiaries – which is a complicated term in and of itself – the first gendered effect that comes to mind relates again to the way care labour is gendered and racialized.

One of the clearest pieces of evidence about the poor policy outcomes that are produced through these strategies and also how they erode human rights is in the health sector.

The case of India, which we detail in our report, is one of the largest public-private partnerships in the global South: a health insurance scheme for people who live in poverty. And through the implementation of the insurance scheme, what we found is that the number of C-sections – including unnecessary C-sections – and unnecessary hysterectomies increased. Indeed, the number of these interventions went through the roof, especially among women who are of lower income groups, among women who are of racialized castes.

So, we found that these women were not offered alternative treatments for things that had alternative treatments in other circumstances. And of course, it became again an issue of profit over rights. This is why I was speaking about how PPPs create the wrong set of incentives altogether: policy is no longer about health provision and outcomes, but private gain.

The Zimbabwean case, where they partially privatized one of the most important hospitals in the country is also instructive. Privatization created staffing issues. Staff were more available and willing to provide services for those who could pay out-of-pocket services. And those that could not pay, who represent 90% of women in a maternal health hospital, bore the brunt of the lack of services. Privatization thus has the potential to cost human lives, as we have anecdotal evidence of one maternal death due to unavailable staff.

Lastly, if we want women to be able to participate in the labour market, we need to guarantee the services and the infrastructure that would enable them to actually reduce their unpaid labour load and then have the possibility of increasing their paid labour load. Because otherwise they just don’t have the time, or even the incentives, to participate in an economic system that is actually pushing them out.

CRE: In the cases we developed at DAWN, what Masaya describes was clear, for example, in Ghana. The Ghanaian case looked at developing infrastructure for a street market where women were mainly the ones who were there selling their products. It’s very clear how the infrastructure they created was not necessarily what women needed. It also made it costlier for women to be able to occupy the space in the street market. So, in fact, something that we can think “oh it’s good for these women to have infrastructure there, a little roof,” but then it was more difficult for women to access that space.

We also have a case in Sierra Leone from the energy sector in which it’s very clear that the PPP displaced people. They provided them with a kind of “replacement” of what used to be the source of their livelihood that, of course, didn’t meet what they needed.

I would like to add two more ways that PPPs affect women and girls. One is the impact on women’s labour rights and conditions. In many sectors, women are among the workers of the PPP projects, and labour conditions become more precarious. And the second one is the impact on women as human rights defenders and defenders of the Earth. When people organize and resist these projects, women are often leaders of this resistance. They are criminalized and are prosecuted by the companies. So, the impact on women as human rights defenders is also relevant.

AM, SS: Corina just mentioned that a lot of these ecological movements and anti-privatization movements are led by women. So, what are women and girls and other folks doing to contest the PPP agenda and its harmful impacts? Tell us a little bit more about the resistance that you’ve seen.

MLB: It’s a big question. The first approach that I think has been taken by different groups is the idea of bringing the state back in. In a way we idealize the state as always a fair and transparent actor. We know there are many problems with it, but the state, at least in principle, has the duty to protect human rights of the its citizens, and hopefully, also the inhabitants of the territories that it governs. So, the state is an interlocutor for movements to engage with, in relatively fair terms, or less unfair terms, as it is when citizens and people in general are trying to tackle corporations who have, in principle, no need to enter into conversation with the general public. Corporations are accountable to themselves, and the state should be accountable to people. So, bringing the state back in is the main way to go.

This has many forms and shapes. In the case of Ghana, for example, street sellers protested in front of the market, in front of their MPs, and they also brought this conversation into the electoral processes in a way that favored them. And, in fact, their campaign made this state come back. This is one of the cases in which we found civil society effectively bringing possible positive results, or at least, results that created some form of optimism.

I think another aspect here is the importance of broad coalitions. Unions are an important aspect of civil society mobilization around this. In the issues in the case of health, for example, nurses are at the forefront of asking for the public disclosure of contracts, of asking for public consultations. And this is not, you know, a coincidence. It is often nurses which are amongst the lowest paid of health workers, who are bearing the brunt of these privatization processes. They’re often asked to subsidize the system with their unpaid or underpaid labour. So, these broad coalitions are a very important strategy, and it’s a strategy that we see at play. It’s not a recommendation of ours; it’s something that is already happening.

Our research at DAWN aims to situate these processes that seem to be very local and very specific to every national context, and to place them into a global context. And demonstrate how they are part of a global process in which the development discussion is being privatized. This is hard to see when you’re on the ground and you’re facing the privatization of the one health service that you access. You’re often too busy with survival to be able to see the larger picture.

So, with our research we have the opportunity to say, “Hey, this or that is happening in a particular hospital in an island of Fiji is very similar to what is happening in Peru, or to what is happening in Zimbabwe.” And there are all these common patterns that we can see and put together and that link up to global governance processes quite clearly. So, it’s not only about producing evidence, which is a main aspect of our work, but it’s also about putting it together and showing how these are not isolated cases, but it’s a systemic problem that needs to be tackled systemically.

CRE: Resistance often erupts where the PPPs happen, that is, locally. But this agenda is a global one. We also need to make international financial institutions accountable. The World Bank, for example, is a big-time promoter of PPPs, but we also need to make governments in the global North accountable because they are also the ones pushing for the corporations of their countries to be profiting from this process. So, I fully agree that global resistance is also very much needed here. •