7 October 2016 marks the fifteenth anniversary of the invasion of Afghanistan. Many Western leaders claimed the invasion, dubbed Operation Enduring Freedom, was a humanitarian intervention to liberate Afghans and especially Afghan women and girls from the brutal Taliban regime. However, the evidence demonstrates the results have been anything but humane or liberating.

The people truly liberated by the invasion and occupation of Afghanistan are the wealthy investors in the military-industrial complex and those betting on successfully extracting Afghan resources and developing the infrastructure of the New Silk Road.

The people truly liberated by the invasion and occupation of Afghanistan are the wealthy investors in the military-industrial complex and those betting on successfully extracting Afghan resources and developing the infrastructure of the New Silk Road.

The Failure of Humanitarian Intervention

Civilian casualties: Perhaps the crudest measure of the failure of the humanitarian intervention in Afghanistan is to count the growing number of civilian casualties. Mysteriously, no official agency actually counted Afghan civilian casualties prior to 2009; consequently, civilian casualty figures from 2001 to 2009 really are anybody’s guess. Literally, countless numbers of Afghans were killed or maimed during the invasion and ensuing occupation.

The UN Assistance Mission to Afghanistan (UNAMA) only began counting civilian casualties in 2009 recording a trend of increasing numbers ever since. In the first half of 2016, 5166 civilians were killed or maimed – almost a third of these were children.

The total civilian casualties recorded by UNAMA from 1 January 2009 to 30 June 2016 is 63,934, including 22,941 killed and 40,993 injured. UNAMA states: “The figures are conservative – almost certainly underestimates – given the strict methodology employed in their documentation and in determining the civilian status of those affected.”

Anti-government forces account for 60 per cent of civilian casualties; nonetheless, the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Zeid Ra’ad Al Hussein, argues: “Parties to the conflict must cease the deliberate targeting of civilians and the use of heavy weaponry in civilian-populated areas. There must be an end to the prevailing impunity enjoyed by those responsible for civilian casualties – no matter who they are.”

The consequences for Afghans have been devastating. The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights observes:

“The family that lost a breadwinner, forcing the children to leave school and struggle to make ends meet; the driver who lost his limbs, depriving him of his livelihood; the man who went to the bazaar to shop for his children only to return home to find them dead; the broken back and leg that has never been treated because the family cannot afford the cost of treatment; the parents who collected their son’s remains in a plastic bag… In just the past six months, there have been at least 5,166 such stories – of which one-third involve the killing or maiming of children, which is particularly alarming and shameful” (UNAMA 25 July 2016).

Refugees: Another crude measure of the failure of the humanitarian intervention is to count refugees in what is a growing refugee crisis 15 years after the invasion. But, like civilian casualties, no official agency counted refugee numbers throughout most of the occupation.

According to the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) conditions deteriorated in 2015 with renewed fighting causing the internal displacement of 245,000 Afghans in the first half of 2016 swelling the number of internally displaced persons to more than 1.2 million.

The UNHCR observes that an estimated 1.5-2 million undocumented Afghans refugees live in the Islamic Republic of Iran and another million in Pakistan. Western media has recently focussed almost exclusively on Syrian refugees, but the UNHCR documents that, since 2015, Afghans have constituted the second largest group of refugees arriving in Europe (UNHCR 23 Sept. 2016).

The Failure to Liberate Afghan Women and Girls

Western media and even many Western women’s organizations continue to portray Afghan women as passive victims who needed intervention by a military force to liberate them from a misogynistic regime. However, many women I met in Afghanistan argue the ongoing war impedes their own struggles for liberation.

Prior to the invasion, Afghan women were focussed on resisting the misogynistic policies of the Taliban regime in the South as much as on those of the United Islamic Federation aka Northern Alliance in the North. Since the invasion, however, women’s energies are often redirected to merely surviving or attempting to escape warfare. Moreover, installing the misogynistic regime of the United Islamic Federation aka Northern Alliance in power to replace the misogynistic Talib regime changed little for Afghan women. Some argue this regime change actually legitimated misogyny.

One women’s activist I met in Afghanistan used the example of women in Iran to make her point. Indeed the regime that seized power in Iran in 1979 was one of the most brutally misogynistic imaginable. But Iranian women resisted the regime to the extent that today they enjoy some of the best conditions in the Islamic world – certainly conditions significantly better than those suffered by Saudi women, despite the irony of unwavering Western support of the Saudi regime.

Some Western feminists continue to focus on what clothing Afghan women choose to wear, but arguments about the burqa and hijab are red-herrings. These are not the real issues facing Afghan women confronted with far greater problems.

Violence against women: A recent UNAMA study finds that while the new legal framework of Afghanistan criminalizes violence against women, in reality numerous factors block women’s access to justice. (UNAMA April 2015)

I have found no documentary evidence to show violence against women is less of a problem today in Afghanistan than it was prior to the invasion.

Health and welfare: Afghanistan has by far the worst infant mortality rate in the world at 112.8 deaths per 1000 live births, one of the worst maternal mortality rates, at 460 deaths per 100,000 live births, and the third worst life expectancy at 51.3 years. These horrific health statistics are not surprising considering that even the basics of clean drinking water and sanitation facilities still remain inaccessible to large numbers of Afghans 15 years after the invasion. Moreover access to healthcare is extremely limited with only 0.27 doctors per 1000 Afghans (CIA World Factbook 2016).

Forty-three per cent of Afghans still do not have electricity, which disproportionately affects women and girls in a traditional culture in which they are burdened with water collection, food preparation, and cleaning (CIA World Factbook 2016).

Afghan women focussed entirely on caring for their families in these conditions have little time and energy left for organizing resistance against a misogynistic regime.

Education for girls: Throughout the occupation, numerous reports have cited encouraging statics claiming millions of Afghan girls are attending school. Unfortunately, inflated enrolment statistics do not reflect the reality that vast numbers of Afghan girls as well as boys do not have access to education. There have been modest improvements in some areas, but overall access to education remains a dream for vast numbers of Afghan children, especially girls. The female literacy rate remains at 25.3 per cent (CIA World Factbook 2016).

The failure of the humanitarian mission to liberate Afghan women and girls might be chalked up to bad planning and overall incompetence. But the more plausible explanation is that the humanitarian-liberation mission has never been a priority – this mission is a politically acceptable façade for the geostrategic mission to liberate capital.

The Success of Liberating Capital

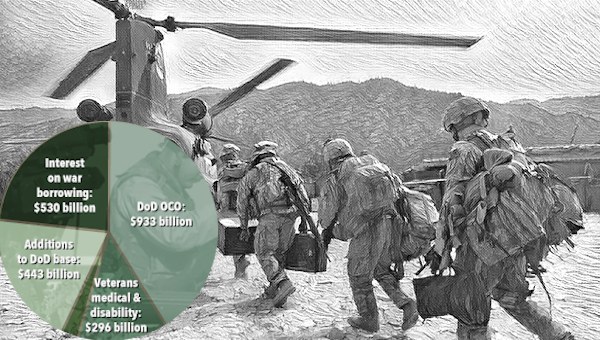

Since George Bush declared the beginning of the Global War of Terror on 20 September 2001, the cost to the United States to date is $4.79-trillion (U.S.) (Crawford Sept. 2016). The costs to the other NATO and coalition states would undoubtedly add many more hundreds of billions of dollars to this figure.

This unfathomable sum is a cost to taxpayers, but it is a profitable return on investment for investors in the military-industrial complex. Rather than money lost, it is in fact money liberated from public coffers to be transferred to the private pockets of a few wealthy investors.

Extracting Afghan Resources: In 1808, Captain Alexander Burns of the British East India Company led a team of surveyors into Afghanistan in an attempt to exploit its resources ahead of Russian competitors. However, Burn’s paramilitary expedition had greater success in propelling the British East India Company into the First Anglo-Afghan War of 1839-42.

Another captain of the British East India Company, Henry Drummond conducted surveys during the First Anglo-Afghan War. Drummond wrote that the company’s paramilitary invasion of Afghanistan would not be perceived as an “act of aggression” because the reorganization of the existing system of Afghan mine management and improvements in the working conditions of Afghan miners would lead to an “era of peace, prosperity, and of permanent tranquility in Afghanistan.”

Also during that war, the British envoy to Kabul, Sir W.H. Macnaughten, wrote that developing Afghanistan’s resources would employ the “wild inhabitants… reclaim them from a life of lawless violence” and increase the wealth of Afghans as it increased the wealth of the British East Asia Company.

Despite fighting three wars in Afghanistan, (1839-42, 1878-80, 1919) the British could not establish control over Afghan territory to develop resource extraction operations.

A Soviet surveyor, Vladimir Obruchev, published a detailed geological report in 1927. The Obruchev depression in the natural-gas rich Amu Darya Basin still bears his name. Then in the early 1930s, the Afghan government granted the American Inland Oil Company a 25 year concession to oil and mineral exploration rights, but the company soon backed out of its agreement.

Following the Second World War, the Afghan government sought technical and financial assistance from American, European, Czech, and Soviet sources often pitting First-World and Second-World surveyors against one another. By the 1970s more than 700 geological reports indicated that a vast wealth of resources awaited exploitation.

From the 1970s to the 1990s Afghans derived much of their foreign exchange from natural gas sales to the USSR.

Thus, following the 2001 invasion, a first order of business was for the U.S. and British Geological Surveys to conduct extensive exploration with the assistance of the Canadian Forces Mapping and Charting Establishment.

In 2010, New York Times journalist James Risen broke the news that Afghanistan contains a vast wealth of natural resources. Risen’s claim that U.S. geologists merely “stumbled across” some old surveys to make their discovery seems somewhat disingenuous considering the long history of foreign interest in Afghan resources.

If the U.S.-led Operation Enduring Freedom invasion of 2001 accomplished nothing else, it secured the freedom for foreign investors to profit from extracting Afghanistan’s resource wealth. The occupation forces destroyed the last vestiges of Afghanistan’s poorly developed and badly broken state enterprise system.

The U.S. Department of State reported in 2010 that Afghanistan “has taken significant steps toward fostering a business-friendly environment for both foreign and domestic investment.” Afghanistan’s new investment law allows 100 per cent foreign ownership and provides generous tax allowances to foreign investors without protections for Afghan workers or the environment.

The strategic value of Afghanistan’s rich resources rests, nevertheless, more in their catalytic potential to attract investors to the region than these resources actual use or market values. Whether these investors are American, Chinese, Russian, Indian, British, Canadian or anyone else matters little, provided they invest within the rubric of the American led global capitalist regime. More importantly, investments in resource development are an essential catalyst to develop the infrastructure of the New Silk Road.

The New Silk Road and the Regime of Global Free Trade

Influential geostrategists have argued since the collapse of the USSR that the nation that dominates trade in Eurasia will dominate the globe. The shortest routes between China and Europe, as well as between India and Russia, pass through Afghanistan. Railways, highways, oil and gas pipelines, electrical transmission lines, and fibre-optic cables will inevitably criss-cross Afghanistan to connect Eurasia. As in previous imperial ages, the empire that achieves primacy is the one that, among other aspects of power, establishes itself as builder, protector, and arbiter of trade routes.

During the past half millennia of the emergence of capitalism, empires expanded in the pursuit of various commodities – spices, fish, furs, indigo, cotton, rubber, and gold among many others. The strategic importance of various resources wax and wane with changes in technology or even the whim of consumers. Nonetheless, what remains as a constant is the growth of the physical transportation, energy transmission, and communications networks as well as the less tangible but no less real political-legal-economic infrastructure of empire. Geostrategists recognize that building this infrastructure of dominance is ultimately more important to securing power than merely acquiring specific resources.

Consequently, on 20 July 2011, U.S. Secretary of State, Hillary Clinton announced the New Silk Road strategy. She stated the U.S. and its partners will build a New Silk Road across Central Asia including Afghanistan as an “international web and network of economic and transit connections.” “That means,” Clinton said, “building more rail lines, highways, energy infrastructure … upgrading the facilities at border crossings … and removing the bureaucratic barriers to the free flow of goods and people.” She also stated: “It means casting aside the outdated trade policies that we are living with and adopting new rules for the 21st century.”

The new rules Clinton refers to are the political-legal-economic infrastructure of an empire of capital. A primary objective of the geostrategists plotting the emergence of an American led empire of capital is to globalize this political-legal-economic infrastructure – the regime of capitalist social relations.

The value of Afghanistan’s resource wealth lies then not only in its actual use or market values, but also in its value to catalyze expanding the physical and the less tangible but no less real political-legal-economic infrastructure of an American led empire of capital.

Despite the fact George Bush declared a Global War on Terror on 20 September 2001, many perceive the battles in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, and Syria, the lesser-known military operations in Haiti, the Philippines, the Horn of Africa and Latin America, the never-ending battles in Palestine, as well as the many worldwide covert operations of U.S. and allied Special Forces as separate individual wars. However, all these struggles are interrelated battles of one global war.

“The primary objective of this global war is regime change… a deliberate pogrom of fundamental regime change with the objective to destroy whatever socioeconomic order existed before…”

The primary objective of this global war is regime change. However, this is not regime change in the sense of 20th century history when a ‘bad’ ruler would be replaced by a ‘good’ or perhaps ‘less bad’ ruler, or even a ruler we really cannot abide but who might at least stave off chaos. This is, instead, a deliberate pogrom of fundamental regime change with the objective to destroy whatever socioeconomic order existed before, whether socialist, or Talib, or Ba’athist, or any variety of traditional tribal communitarian society.

The claim that this global war is about eliminating terrorism, promoting democracy, or in the case of Afghanistan liberating women provides politically acceptable façades to legitimate the primary objective of creative destruction – the destruction of any preceding socioeconomic system to be replaced by the capitalist social order.

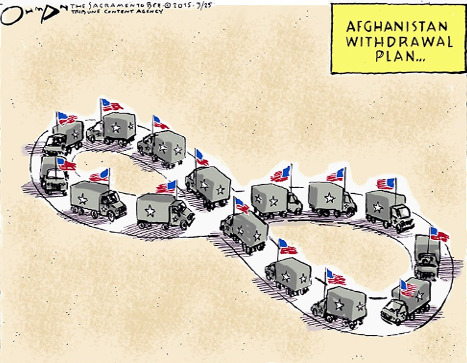

This is a multi-generational pogrom. The NATO states are currently committed to maintaining military forces in Afghanistan until 2024 to secure an “Enduring Partnership” (NATO 2014).

Considering that pacification of the many Peoples of the western territories of the U.S. took more than a century, this is likely just a beginning.

The enduring legacy of the Operation Enduring Freedom invasion that began 7 October 2001 is that Afghans – for both better and worse – are left to endure the freedom of investors to dictate the future of Afghanistan. •

This article was published online 7 October 2016 at Michael Skinner Research and is reprinted here with his permission.