Just about everyone in and around the union movement in Canada is talking about the upcoming merger between the Canadian Auto Workers (CAW) and the Communications, Energy and Paperworkers (CEP). The new union being formed will be the largest private sector union in Canada.

While bigger is not necessarily better – as numerous other examples of larger mergers have shown1 – in this era of general unions, the new union should become a positive force on the Canadian labour scene. Both the CAW and CEP have strengths in different but complementary sectors and geographical areas; their pooling of resources should help address some of the membership losses in each (a problem throughout the entire private sector) as well as provide needed collective resources for research, education and organizing.

But the CAW and CEP – in their public documents and speeches at the recent CAW Constitutional Convention – aspire to greater things. At a time where the Canadian union movement is at a strategic impasse and a steep organizational decline, the new union they will form is being touted as a key element in turning the situation around, through a larger project of union renewal and a major response to the attacks on the working-class and labour movement. One has to be very careful in assessing these rather lofty aspirations.

The new union will be shaped and limited by neoliberal capitalism, the structures and experiences of the larger working-class and labour movement, and the particular limitations of unions in this era. Whatever changes the new union plans, it must take into account and address these limitations and imperatives.

There are some important and exciting potential contributions that the new union project argues for and can make. They should be encouraged and supported, with a number of caveats.

But the huge challenges that the new union talks about addressing require a larger project of change that goes beyond the current capacities and contradicts many of the approaches (and practices) of the component unions. As well, they depend on a series of larger political projects that currently do not exist and that the component unions are not likely to initiate.

Context, Limitations and Openings

The new union is being formed at a time where unions and the working-class as a whole have experienced numerous attacks, setbacks and defeats. Unions are politically and organizationally isolated and weak. This is dramatically different than the moment when the CAW itself was formed.

In the 1980s, the Canadian section of the UAW and later the new union (the CAW) – often in partnership with social activist movements outside of labour and sometimes with other unions – waged a battle to challenge free trade and continentalism (with demonstrations, grassroots education with members and the general public). It mobilized against the austerity agenda of the time and, most importantly, took on the major auto companies as well as the latter’s union partners/enablers in the UAW. By refusing concessions, and asserting the need for the union to maintain its independence from employers and reject competitiveness as a goal, the UAW’s Canadian region inspired its members and huge numbers of Canadian working people and, in the process formed a new union.

The formation of the new union didn’t signal an end to these struggles but their continuation. This helped to create conditions for more intensified efforts to challenge the growing tide of neoliberal transformation. The new union in 1985 inspired other members of the working-class and the larger progressive community in Canada and led to a healthy, growing union.

The effort to create a new union out of a merger between the CAW and CEP today takes place in a completely different context. Neoliberalism has moved apace, and has all but defeated and marginalized many private sector unions, radically segmented the working-class, creating huge material and experiential gaps between those on social assistance, in precarious market segments and those with more secure and better-paying jobs. Many unionized workers – and the bulk of the rest of the working-class – have never participated in collective struggles. Many have been forced to rely in individual strategies to keep afloat and this has helped to shape their understanding of society and their role in it.

Unions – particularly in the public sector, but also in others, such as auto – are isolated in many ways from the rest of the working-class. Even in the better-off labour market segments, unions have given up concessions both in wages and benefits, as well as in their workplaces. This helped to demoralize much of the membership, but also distanced those whom the unions seek to organize.

Politically, unions have not challenged the system. With the utter defeat of the radical left, which once served as a pole of reference beyond capitalism, they have tried to “hold on” to what they had, and nostalgically return to the good old days of the welfare state and partnership with employers and governments. On the other hand, continentalism, free trade, export dependency and managerial demands for concessions have all but been accepted by the labour movement, including the two unions that are merging to form the new union project (as well as all major political parties).

Unions are tied to the success of particular employers in individual sectors, and are bound to look after the interests of their dues-paying members who work there. In an era where the better off workers were able to set patterns for others, this didn’t seem as limiting as today. But in this era of advanced neoliberalism – with masses of unemployed, poor, precarious workers – it separated out unions from other workers, with devastatingly harmful results. Unions are seen by much of the class as being privileged.

Rather than being part of an ongoing resistance movement, the new union project takes place in an environment of defeat and those forming the new union (leaders, activists and many rank and filers) have been shaped by that experience as much as other unions and components of the working-class. They are frustrated by those defeats and claim to want very much to move beyond them. But they remain very much limited by them, not having really studied or learned the lessons from them, fully accepting the limitations as defined by the corporations.2

“The critical factor remains, the larger disorganization and defeat of the working-class as a whole, the strength of neoliberalism, the limitations of unions as they currently exist and the lack of any real political or organizational alternatives that address the need to create a class-wide movement.”

In order to address this set of limitations, the new union – and the rest of the union movement – needs to change what it does. Unions across the developed capitalist world often talk about embracing new strategies: big mergers, renewal programs, spending more on organizing, and so forth. But the critical factor remains the larger disorganization and defeat of the working-class as a whole, the strength of neoliberalism, the limitations of unions as they currently exist and the lack of any real political or organizational alternatives that address the need to create a class-wide movement.

Who are the CAW and CEP and what do they bring to the table?

The CAW has been one of the predominant private sector unions in Canada, since its founding in 1985, as a split-off from the American International Union, the UAW. At one time it had 265,000 members and, although its base was in auto and the manufacturing sector, it spread across sectors as diverse as airline, general manufacturing, public sector, services, rail, fisheries, etc. The union has always played an important role in shaping the lives of union members and the working-class as whole. Collective bargaining in core sectors such as auto set patterns for wages and benefits across the country and its political role in larger campaigns at one time was a critical part of the working-class movement in Canada – as are its more recent difficulties in dealing with the crises of its major employers. It also has tremendous resources in bargaining expertise, worker education (spends more than all other unions combined and has its own educational centre), and in research capability.

The CEP is concentrated in other key sectors, such as Communications, Resource Extraction and Energy, major strategic components of the Canadian economy. It has had to deal directly with key transformations in broadcasting, newspapers, mining and forestry and energy issues – all of which have been central components of neoliberal restructuring in Canada. It, too, has participated in a number of political campaigns, and has a history of building relationships between energy and resource extraction workers and environmentalists and local communities. The new union will combine some 300,000 workers across the country, in strategic sectors such as Manufacturing (94,000); Communications (41,000); Resources (52,000); Transportation (40,000); Services – including public sector – (76,000).

Membership will be spread throughout the entire country, in every province and territory except Yukon and Nunavut. It will have more than 86,000 women, and, “tens of thousands of aboriginal and workers of colour.”3 It will include more than 800 local unions and over 3,000 bargaining units.

Linking Up with the Rest of the Working-Class

A key feature of the plan for the new union is its approach to organizing and community unionism. It pledges to “organize and mobilize workers” such as the unemployed, members who join in unsuccessful organizing drives, individual, non-unionized workers, working in precarious, temporary, contract, self-employed, and freelancers and students and other young people. It claims that, “this is crucial to allow us to involve a broader range of working people in our mission to build a powerful social movement fighting for all working people.”4

These are stirring words. Many on the left have been calling for such a development for many years. The component unions should be congratulated for it. It has the potential to alter the role of the new union in its relations with the segments of the working-class that have been most affected by neoliberal restructuring of labour markets. There are precious few unions around the world that have experimented with this open membership concept, such as the CTA in Argentina.

But the proof of the pudding is in the eating. Making this work requires a major rethink of how the union relates to workers and communities outside of it. It calls for new ways of doing things and an opening up to the experiences of other activists. At the very least, it raises a number of thorny questions, such as the role of individual membership inside the union’s structures; forms of support for individual or groups of workers in non-unionized workplaces and relations with existing social movement and community activists and organizations.

This effort must be undertaken as a project of contributing to the organization of the class. A common class project could contribute to breaking down the narrowness and limitations of both the unions and the social movement left’s projects. But a narrower approach, seeking primarily to strengthen the union itself could have the opposite effect.

These questions can’t be seen as separate from the other things the union must do to inspire youth, as well as unemployed and precarious workers, such as fighting employers, resisting concessions and fighting for new ways to create jobs that are not dependent on the competitive success of individual capitalists. The CAW and the CEP – and the rest of the labour movement – have not proved capable of doing this all that well. The new auto contracts that cement wage and pension inferiority for ten years for junior workers, only worsens the problem. It is part of what must change to make this new strategic approach work.

Engaging in a genuine attempt at social movement unionism clearly raises some difficult questions that need to be considered and tackled. The attempt itself is an important breakthrough.

Organizing

Along with the individual membership and opening up to the community, the new union will dramatically increase resources for organizing. It is committed to developing a ‘culture of organizing’ across the union and is putting 10 per cent of its national dues revenue to this project. This will mean $50-million over the first five years of the union’s existence, doubling what the two unions currently spend.

Here again, how this is done makes a big difference. International experience shows that spending money and making claims about building an organizing culture doesn’t necessarily result in increased union density.5 The union needs to work together with others to make organizing part of a larger class project, and move away from the current competition for new members, between large, general unions.

Unions have had very mixed success with organizing in sectors where precarious work is predominant. It requires collective efforts between unions to work together to organize across entire sectors (right now, they compete with each other). Will the new union be willing to change the current approach, which is to see organizing as a way of strengthening its own capacity to act, rather as one element in a larger class project, or building the capacity of the entire working-class? Perhaps the union could start by inviting CUPE, SEIU, the Toronto Workers’ Action Centre, and organizations based in immigrant communities that predominate in this sector and others, to collectively organize homecare workers.

Workers will not join a union, no matter how big or how much money it spends, if they think that it will not give them any real capacity to protect themselves against their employers. Years of concession bargaining, especially give backs of time off the job, break time and ending efforts to challenge lean production practises in the workplace (in order to increase productivity so as to protect wages and benefits) on the part of the CAW, makes workers at Japanese transplant auto plants less likely to sign union cards. Successful organizing requires substantial changes, not only in the way unions organize, but how they defend workers interests – in the workplace and in society as a whole.

And, as well, today, given the constant threats of job loss for those with jobs, and the frustration, anger and resentment of those in the precarious sectors, it requires a larger sense that the union is part of a movement that can shape the economy and actually limit the larger power of the employers.

Two Divides Into One…

Merging two unions doesn’t easily translate into a ‘new’ union. There are all kinds of forms of organization and cultural dissonance that needs to be worked out over time. The CAW’s organizational structure is highly integrated and tends to be led from the centre.6 CEP has its own regional power centres, and the different components of that union are said to operate as ‘silos.’

In the recent period, there remains a tradition of autonomous dissidence within the membership and different layers of the activist core in the CEP (some of it more, some less progressive in the political sense), while the CAW’s leadership core, along with the effects of neoliberal restructuring and the defeat of the left have more or less defeated efforts to create any autonomous organization of members or activists.

The CAW’s tradition of recognizing the national identity of Quebec and, therefore, the need for organizational autonomy for the Quebec section of the union – quite remarkable, as it reaches across many different elements in that union – came up against people within the CEP that did not.

The two unions embarked on an extended and rather unique process of building the merger. They put together a Proposal Committee which adopted a series of principles, and worked their way through the elements of the merger, keeping these principles in mind. The result was a proposal for a series of new structures and components. This has been approved by the CAW and will be voted on by the CEP later this year. If the latter approves, a series of working groups will be set up to “facilitate the preparations for the foundation of the new union” and a founding convention will be held.

A number of the new structures outlined by the Proposal Committee seek to merge elements of the different organizational cultures, dominated by many of the institutional practices of the CAW. These include a series of four regional councils with elected delegates from locals, along with a number of Industrial Councils. There will also be a larger Canadian Council that will meet once per year. There will be an autonomous Quebec Council.7

The idea was to create councils where issues could be raised and debated by elected delegates from local unions; build structures that accommodate the large size of the union and combine the regional and more decentralized practises of the CEP, along with the CAW’s more centralized traditions. The operations of these councils (as described in the new union document), seem to track the existing practises of the CAW Council: the meetings will be centred around reports from the elected leadership to the delegates, with the reports shaping and dominating the procedure and content. This provides a potential to hold the leadership to account, and allows the latter to introduce campaigns and bargaining issues, as well as political and economic questions it deems important. On the other hand, it also replicates tendencies that limit the initiative and role of activists from the local unions.8

Responding to the Attacks

The new union documents and the debate at the August CAW Convention talk about many of the challenges that the labour movement and the working-class are facing today. They identify key elements of attacks against the working-class, as well as important weaknesses and shortcomings of the labour movement itself in having mounted such feeble resistance.9 The documents lament the inability to oppose concessions, build a political response to what they identify as ‘neoliberal capitalism,’ and even recall key moments of collective resistance, such as the Ontario Days of Action and the BC Solidarity movement.

The documents claim that the new union will become a key space for a larger effort to respond to these potentially mortal attacks and major weaknesses.

An element of the new union’s aspirations in fostering renewal, is the union’s claim to reinvigorate the collective fightback of labour, to “inspire,” “push” and “embarrass” existing labour centrals into “more forceful vision of action … [to] articulate a broader critique of the current…system (neoliberal capitalism) and position itself as fighting for long-run social and political change, not just incremental economic progress for its members.”10 The CAW Constitutional Convention was rife with fiery speeches about the collective desire to build a new and wider resistance movement. The feeling was powerful and palpable across the union’s political and organizational spectrum, and in the guest speakers from CEP as well.

But to be serious about making these aspirations a reality, requires changes in approach and orientation that are very difficult to put into practice and, given the actions and experiences of the constituent unions and the larger labour movement, require major changes to move forward. What are some of these changes?

First, power has to be rebuilt in the workplace. The workplace shapes so much in the working-class experience: our power and our of lack of it; the authority and legitimacy of business, its decisions and interests; our sense of what we can and can’t do collectively, the notion of independent worker and employer interests, etc. Workers often learn about who and what unions are and can be, through their collective experience in struggles in the workplace – alongside union activists willing and able to do education together. The neoliberal era has seen a steady erosion in the protections that workers have in the workplace, the rise and institutionalization of lean production norms, and the increasing acceptance by many unions (including the CAW) that concessions in wages and benefits can be minimized (or hidden) by increasing work intensity, reducing break time and giving back time off the job. Workers in and outside of union workplaces (and even those not working) know this and it limits their interest in collective organization as well as unions. This needs to become a key battleground for a new union to begin to re-establish the support and power of the workers. It has, unfortunately, been a site of key defeat and setbacks. This must change, but as of yet there seems to be neither recognition of the defeats in the workplace nor the necessity of building independent collective power there.

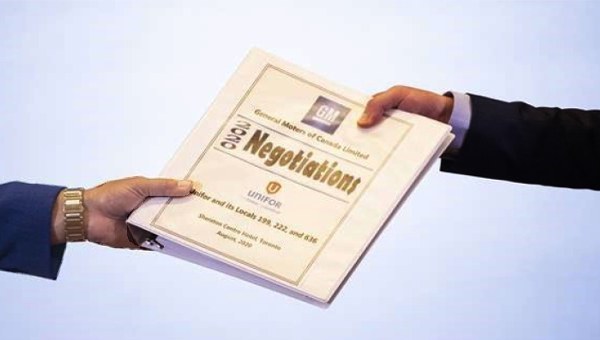

Second, they require an aggressive and solidaristic approach to key collective bargaining struggles. In their documents, the unions acknowledge that employers have dug in their heels in key areas, and that the labour movement has been unable to mount the kind of sustained and wide scale campaigns necessary to win. Unfortunately, the collective agreements recently bargained by the CAW at GM and Ford (talks still continue with Chrysler) move in the opposite direction.

The auto companies have once again become profitable, yet remained locked-in to demands for further cost reductions and concessions from the union (such as permanent two-tier workers, elimination of 30-and-out pensions, etc.). They operate in a brutally competitive economic environment, but don’t most capitalists these days? The auto companies are using the rise in the dollar’s value, the sluggish and tentative economic recovery and workers’ fear of job loss and lack of new investment to enforce a sense of powerlessness and dependence.11

The terms of the agreement (and the rhetoric underpinning it) demonstrate that the union fully accepts and accommodates the logic of the companies – that ongoing worker concessions are necessary to solidify their unstable and fragile profitability. They and the companies are not divided over whether or not to accept further concessions, but over what they are and how long they might be expected to last. The CAW offered to reduce wages and benefits for new hires that ‘grows-in’ to the full rate over a period of 10 years (in exchange for investment commitments) – an offer that has been accepted by Ford and GM. The agreement also includes a “hybrid” pension for the new hires (elements of defined benefit and defined contribution pensions), along with wages that start at 60 per cent of the normal rate.12 Current workers will see no basic wage increases or cost-of-living adjustments, but lump sum bonuses will substitute for both over the four years of the agreement. There are also a series of employment commitments, as well as a seemingly successful effort to restrict the highly unpopular uncontrolled use of temporary workers in GM plants.

The union (and unfortunately, all too many analysts and commentators) claim that this is some kind of a victory – citing the difficult objective circumstances and the fact that since the two-tier workforce would ‘only’ exist for 10 years, rather than permanently.

What effect will this have on the solidarity of the workers in the workplace, and how will it affect efforts to organize younger workers into the union? Just as in American plants, the divisions between the cohorts of workers – tracking age and generational differences as well – will of necessity challenge efforts to renew the union and build a new sense of solidarity and independence from the employer. Even more, the acceptance of this form of two-tier-by-stealth, along with the ‘hybrid’ pension formula for new hires, will undermine efforts of the rest of the labour movement to oppose them in their workplaces and sectors. What does it say about the claims of the new union to lead a movement of resistance and struggle?13

Bargaining is only one part of what unions need to do to establish their capacity to resist and build alternatives. And the larger political-economic context affects the relative balance of forces between labour and capital. But this set of contract talks will go far to shape who and what the new union will look like – and the honesty and sincerity of the tough talk at the Convention and in the press.

Third, the two new union documents and the speeches at the CAW convention talk about building alternatives to the current economic and political environment that shapes collective bargaining as well as the lives of workers. What can we expect of this?

At the very least, for the new union to take this seriously would require both unions to rethink their current approach to political and economic reforms, their relationships with employers and the state and their analyses of the sectors in which they operate, as well as how they engage in politics. Both the CAW and CEP have political approaches that involve some form of partnership between the unions, private sector employers and the state, and do little to transform the larger economic and political environment.

At the very least, for the new union to take this seriously would require both unions to rethink their current approach to political and economic reforms, their relationships with employers and the state and their analyses of the sectors in which they operate, as well as how they engage in politics. Both the CAW and CEP have political approaches that involve some form of partnership between the unions, private sector employers and the state, and do little to transform the larger economic and political environment.

The CAW’s principal legislative demand for job creation – according to its Collective Bargaining and Political Action Program – is a call for a “national summit to implement a National Jobs Strategy” that includes “federal and provincial governments, major business sectors, municipal leaders, labour and other economic stakeholders.”14 The CAW’s auto policy is geared toward enhancing the capacity of the current employers to maintain and increase investments in Canada, and, across the larger economic spectrum, intensifying manufacturing and export capacities in “high-value, high tech” sectors. Further, it calls for “more carefully regulating resource industries, and taking active efforts to maximize Canadian value-added opportunities associated with resource extraction.”15

While developing manufacturing capacities are critically important, the union accepts the limits of the current framework of complete domination of economic activity by export-oriented or resource-based private sector firms, operating in highly competitive markets. Even in its calls for lowering the value of the Canadian dollar, it does so, in the context of advancing the competitive export advantage of the private sector firms which dominate the sectors in which it predominates.

The CAW acts as if it wants to be ‘respected’ and considered to be part of the larger establishment conversation – as a ‘legitimate’ stakeholder – by the state and the capitalist class. This helps to explain the invitation recently given to Bank of Canada Governor Mark Carney, the ‘pride’ in having him engage with the Convention, and the fact that they invited him instead of speakers who call for nationalizing the entire financial sector and running it as a democratically-controlled public utility, as a way of challenging the underpinnings of neoliberalism.

CEP has an extensive and interesting set of demands in the energy sector, calling for public ownership, the repeal of the energy provisions of NAFTA and the development of a “national energy policy.” The latter is to be the result of corporatist project that is the “product of a national debate involving all levels of government, industry, trade unionists, consumers, First Nations and community representatives.” The method of getting to the public ownership is hazy, but at least it is there. CEP also endorses carbon capture and storage and the use of bitumen from the tar sands for refining and use in Canada, as part of a larger industrial strategy, keeping in mind the interests and needs of First Nations. The policy book from CEP does not call for stopping the Tar Sands projects, the continued production of bitumen, or the phasing-out of fossil-based energy sources in a planned manner in order to move toward renewable energy.16

Neither union raises a call for, much less a plan for converting the economy away from fossil-fuel dependence.

But there is potential to be different. The two unions’ collective concentration in key sectors, such as energy, auto and other forms of transportation does literally cry out for an integrated anti-capitalist approach. The new union could argue for a move away from its current dependence on American companies manufacturing and exporting private vehicles in fierce competition with other firms. It could call for taking over closed manufacturing facilities to produce environmentally responsible goods that people need, moving toward a dramatic reinvestment in mass transit across the country, concentrating in urban areas. A nationalized energy sector could direct the massive subsidies already given to the tar sands and oil and gas interests toward a planned move away from fossil fuels and the development of renewable energy sources. Collectively, they could become a political force across the country for endogenous (that is internally-directed) economic investment, arguing for a move away from dependency on the competitiveness of individual firms, and end to free trade and capital mobility and argue for structural reforms that reject the fundamental principles of neoliberalism and capitalism.17

The new union documents call for a reassessment of the way that unions engage in electoral politics. The CAW has stressed strategic voting and, at times, issue-oriented campaigning during elections, while the CEP is more closely tied to the NDP. In his speech at the CAW Constitutional Convention Ken Lewenza talked about all three options. In the current context, the NDP looms large and not just because of the CEP tradition. As the official opposition in Ottawa, it has become a magnet of sorts for a significant segment of progressive Canadians.

“The new union needs to consider a politics that challenges the key elements of neoliberalism and capitalism and argues for reforms which move in an alternative direction.”

But the NDP will not challenge the larger direction of neoliberalism, or resource and export dependency. The new union – like the rest of the labour movement – needs to consider a politics that challenges the key elements of neoliberalism and capitalism and argues for reforms which move in an alternative direction. This is not compatible with a politics that defines itself in terms of social democracy or the NDP.

Any serious attempt toward a politics that challenges the system might require an effort to collectively consider how to do politics differently: doing education with members about the current economic system, asking what is wrong with it, what alternatives can there be to neoliberal capitalism, how a union can contribute to arguing and organizing for an alternative and, thinking about what can be done in the meantime. (At one time, the CAW did organize what it called a Task Force on Working Class Politics. It ended up being a rather interesting snapshot of the political opinions and aspirations of the members, but little else.)

That kind of project is beyond the capacity of any union right now, especially in an environment where the socialist left – which can influence, inspire and learn from such a project – is virtually non-existent. But working to build support for it, amongst the activists in and around the union is an important part of changing that environment.

The Union and the Exercise of Renewal

The desire to renew the union is clear in many of the plans and approaches outlined in the documents. But a critical component of renewal is not addressed. While there are structures that have openings for rank and file participation and initiatives, the new union does little to create an autonomous democratic life in the union, whether in the locals or throughout the new representative spaces, where rank and file members and activists initiate and participate in political movements and argue for policies and approaches that differ from the existing leadership.

In the CAW, large local unions and the elected councils (which are the model for the new union’s institutions) became spaces where the leadership present policies and approaches, and the members ‘respond.’ They are not places where workers bring ideas, positions and proposals (or in organized groups based on competing visions or political approaches), and argue them out. Elections in these bodies (and in key local unions) are often non-contested, and this is celebrated as some kind of vindication of incumbents. Most members accept the policies that come down to them or, if they disagree, tend to lose interest and grumble silently – much like life in other institutions in bourgeois society. Even the recent elections to the NEB were not contested – certainly elections were not seen as spaces to raise alternative views. It reflects the decline in democratic life of rank and file workers and the parallel decline in political literacy and radicalism across the entire union movement.

This also reinforces bureaucratic practices that most unions carry with them, such as the tendency for many full-time union representatives to become accustomed to life out of the workplace or off the line. This creates well-recognized barriers between the stratum of elected leaders and many of the rank and file and activist layers.

The lack of membership initiative and participation – and the closely-related absence of an autonomous political life inside these unions – can be addressed in a number of ways, all of which are difficult: the union needs to be engaged in struggles in the workplace and local communities against employers and governments; and leading, debating and orienting these struggles inside the union’s democratic structures. This should become a means educating and politicizing members. Union education must be tied to summarizing and orienting these experiences. The culture, activities and structures of the new regional councils could move away from activities built around reports from the leadership, and instead encourage member initiated agendas and issues. Traditional leadership and organizational models must be questioned, with experiments such as term limits, rotating of staff or full time reps, and others.

Here again, for autonomous political movements and organizations to become a factor amongst the rank and file and activist layer, there needs to be an activist left working outside and inside the union. In past historical periods a lively internal political life was tied to the strength of radical political parties and organizations, rooted in the larger working-class.

Conclusion

The overall project of merging the CAW and CEP is a positive one. Its plan to allow individual membership and open up to social movements outside of the union brings important potentials for moving forward. But most of the new union’s more ambitious agenda items stand in contradiction to their current practices, the broader structural and political limitations of the era and the component unions’ inability and unwillingness to do what is necessary to challenge the latter. The current set of collective agreements being ratified with the Detroit Three automakers is a case in point.

Changing this requires an active and growing socialist and anti-capitalist left in Canada and North America. But this left today is tiny, localized and isolated from the larger trade union movement. Building such a movement would go a long way toward creating the conditions to allow unions to transform their organizations, relations with the rest of the working-class and a larger politics. •