ONDP Leadership: A Revival of Class Politics?

On March 6-8, 2009, Ontario’s New Democrats gathered in Hamilton to select a new leader. After thirteen years of the lackluster leadership of Howard Hampton, the party turned to Hamilton MPP Andrea Horwath, beating out rivals Peter Tabuns, Gilles Bisson and Michael Prue. Horwath, the youngest of the four leadership candidates and the first woman to lead the ONDP, has generated much excitement in terms of reviving the party from its moribund state. With only 10 seats at Queen’s Park and with less than half (11,500 of approximately 24,000) of party members casting votes at all, this is a daunting task indeed. However, with the choice of Horwath, the ONDP has definitively left the Rae era behind. Unlike Hampton who served in Rae’s cabinet, Horwath carries no such baggage. Her selection marks a clean break from the albatross Hampton could not ditch.

From Days of Action to Party Leadership

Horwath, a community organizer played a prominent role in organizing the 1996 Days of Action against the reactionary Harris government, was elected to the Hamilton City Council the following year, representing a troubled inner-city ward. She went on to win a decisive victory in a 2004 by-election. In her leadership run, Horwath stressed her working class roots and ran an effective campaign with explicitly class-based themes. A vigorous defense of manufacturing jobs and calls for the creation of good jobs was central to the campaign; environmental issues, too, were also addressed in class terms, with Horwath stressing the need to make environmentalism affordable to all Ontarians, via upfront loans to households for green energy technologies and retrofitting. Horwath’s nomination statement at the ONDP convention in Hamilton is worth quoting at length:

We may not be rich but we are powerful. We believe in building a better world. You can knock us down, ignore us, write our political obituaries but we are the people who will keep on going. Knock us down and we will get up again because we are New Democrats. Like every Ontarian we are experiencing change. A week ago the steel mills in the skyline represented work. Now they represent people out of work, an economy ripped apart by neoliberalism. An economy with a gutted industrial base. Those mills represent steel no longer made but also autos no longer made in Windsor, a devastated forestry sector… When we look we see all of Ontario. I was a CAW brat. I went to university because my father had a good job. I would not be here today if it wasn’t for my father’s well paid union job. This economic and social crisis will affect every one of us. When good jobs disappear how many children lose their future? When we lose child care how many families become working poor?

Look at the difference a year has made. The middle class is disappearing and the working class is largely unemployed. We could accept this and adjust, that’s what the other parties say, but adjust to what, growing unemployment lines and growing food bank lines, adjust to this growing discrepancy? Adjust so that those who stole our money can get more of it? We refuse to adjust!

The election of Horwath can be interpreted, to a limited degree, as a rejection of explicit Third Way politics. Bisson, who served in the Rae government and supported the Social Contract, was the most explicit proponent of a Third Way strategy. His campaign called for the NDP to reach out to business, corporate tax cuts and getting tougher on crime. He went so far as to propose that the New Democrats drop their long-standing policy of not accepting corporate donations. Ultimately, Bisson came in a distant third on the first ballot, in spite of the fact that approximately 28 per cent of the ONDP membership is in Northern Ontario and the entire delegation of seven Northern federal MPs endorsed him.

A Turn Left?

There was no explicitly “left” candidate in the race and left groups and individuals within the party divided their endorsements. The Ginger Project, which called for a socialist platform for the NDP, stayed neutral. Early in the race, the Socialist Caucus endorsed Prue (due to his support for a debate on separate school funding and calls for greater democracy within the party), while the Ontario New Democratic Youth endorsed Tabuns; toward the end, the Marxist youth group Fightback declared Horwath to be the most amenable to massive pressure from the working class. MPPs identified with the Left of the party, Cheri DiNovo and Peter Kormos endorsed Tabuns and Horwath, respectively. Both runner-up Tabuns and Horwath rejected calls to move the party rightward and came out against corporate tax cuts.

Tabuns, the former executive director of Greenpeace Canada, put environmental issues at the center of his campaign. The “New Energy Economy” plan to redirect Ontario industry toward green technology manufacturing and installation was certainly among the most progressive and innovative environmental platforms presented by a mainstream Canadian politician; while it did speak of creating markets and making Ontario more competitive, it had a central role for government and certainly did not go as far as the Green Party in embracing market ecology. Having received endorsements from Ed Broadbent and members of the Lewis family, Tabuns was the main choice of the party establishment.

Horwath, meanwhile, enjoyed particularly strong union support, receiving endorsements from OFL president Wayne Samuelson, former OPSEU president Leah Casselman and CUPE Ontario president Sid Ryan, as well as numerous labour councils across the province. Tabuns too stressed his working-class Hamilton roots, and received significant labour support in the Toronto area, including the Toronto Area Steelworkers Council and the ethnically diverse, activist UNITE HERE Local 75. Still, the Horwath campaign had a more effective class-based appeal in a time of global economic crisis, although the Horwath campaign’s portrayal of her as the “Obama” of the contest likely played some role as well.

Horwath’s “Good Jobs” platform calls for a “high road” manufacturing strategy that would offer targeted assistance via tax credits, loans and grants to companies that meet job guarantees and wage and labour standards; additional funds would be available to companies that allow unionization, accept worker ownership and provide education and skills development. The building of light rail systems in Ontario cities is Horwath’s chief job creation strategy, supported by the skilled workforces in the plastics, metals, transportation equipment and machinery sectors.

This is certainly more innovative than the “Get Orange” platform of 2007, which had little to offer working people. This was not a coherent program built around an overarching political vision of a more equal, democratic and sustainable economy. Yet it cannot be assumed that were will be substantive changes under new leadership. It should be pointed out that Horwath was co-chair of the 2007 campaign, and in an

interview for rabble.ca, she was unwilling (unlike Tabuns) to discuss its shortcomings. And the ONDP continues to be unwilling to abandon its hypocritical and opportunistic support for the Catholic separate school system, which contradicts such basic liberal democratic (let alone socialist) principles as the separation of church and state and undermines the important role public schools play in fostering diversity and tolerance. Prue’s call for a debate on the issue within the party was met with hostility from the other candidates. Horwath’s response was particularly outrageous, stating that she was “sick and tired” of the “politics of division” and that such a debate was a diversion from the “real” issues in education such as ESL funding, infrastructure, the closing of rural schools, etc. While these are indeed real issues that need to be addressed, that does not mean that the debate over separate school funding is a distraction.

It is ironic that Horwath condemns such a debate as the “politics of division,” when the Province of Ontario has been condemned by the United Nations for religious discrimination in education. At the convention, the party passed a resolution stating that it remained committed to four systems (English and French, public and separate) with improved funding, but establishes a taskforce to review all aspects of school funding.

Building to Challenge Neoliberalism

The significance of the election of Andrea Horwath to lead Ontario’s New Democrats, the first woman to do so, is itself a noteworthy and historic outcome. Her combative style and stress on issues of particular concern to Ontario’s working class was indeed at times inspiring. Can the party’s structural, cultural and electoral atrophy be reversed? Perhaps.

We should hope so. The socialist Left outside of the NDP (and of course those inside the party) has no interest in seeing the party further weakened. Indeed, by virtue of being the leader of a major political party, she can give voice to issues, perspectives and solutions to public problems that force a questioning of neoliberalism and perhaps even capitalism. The socialist Left would of course welcome such a shift. Despite her class-based political instincts it will take more than Andrea Horwath to achieve such, if indeed she even desires to do so.

Social democracy, whether in Ontario or elsewhere, is not capable of challenging neoliberalism or putting forward an anti-capitalist politics. That is not to say it does not have the potential to contribute in some form. Important debates have emerged in the social democratic parties of Norway and Germany for example which open the door to more progressive and potentially radical politics. However, this is in response to pressures to their Left whether from social movements or ascending anti-neoliberal parties.

Several years ago the New Politics Initiative proposed a democratization of the NDP. The ONDP could borrow some of those ideas and must make efforts to revitalize the role of the individual members and the riding associations, perhaps even rethinking the organizational concept of riding associations as the central administrative-structural unit of the party. New organizational sites must be considered in neighbourhoods, workplaces and virtually. Relatedly, a thoroughgoing policy debate and development project is a necessary aspect to renewal. This may entail the striking of local and regional policy conferences animated with background papers and speakers. Let’s face it, since the expulsion of the Waffle a generation ago the intellectual life of the party has faded.

It’s time to get over the fear of debate, ideas and vision that challenge the dominant orthodoxies even as those collapse into so many piles of rubble.

Even doing so would not reconstruct the ONDP into a force of the socialist Left but it would open up additional space toward building the oppositional forces that are and will be so necessary over the years to come. Tabuns and Horwath both suggested a greater role for the public sector in building an economy of high wage and environmentally sustainable jobs. There is no questioning of the role of markets, financial and otherwise, in shaping our economy and our lives. In the absence of critique there is an enduring and pragmatic progressive competitiveness that dominates (and limits) its policy thinking. Despite Horwath’s protestations that “we will not adjust” to the inequality and destruction offered up by neoliberalism, New Democrats are doing precisely that by not challenging what so clearly cannot work.

New Democrats are not embarking on a process to build an anti-neoliberal political bloc. Should such a formation ever come into being here, as it has elsewhere, the party of the social democrats will likely not be part of it. In France, Germany, and the Netherlands, the lesson is that Left social democrats were pressed to break with social democracy and join with various other radical political currents including Marxist, anarchist, and green.

Ontario’s New Democrats have a moment to define themselves as the economic crisis deepens. Ideas do matter and especially so when there is so much to question. Horwath’s political instincts are telling her that. What is concerning is that there is every indication that electoralism will remain the core feature of the party and all activity will be organized around this. And in organizational terms that means a narrow and conservative professional bloc of political consultants and trade union leaders who have set their hopes and political vision on emergence of a ‘new’ New Deal politics, will continue to direct the party. The culture and structures within the party, as they exist, won’t provide Horwath with the material to work with. The revitalization of the membership through a radical democratization of the internal life of the party coupled with an equally thorough effort to debate radical ideas and alternatives will likely not be the chosen strategy. Progressive competitiveness wrapped in the language of a class-based economic populism and sold during electoral contests won’t be enough.

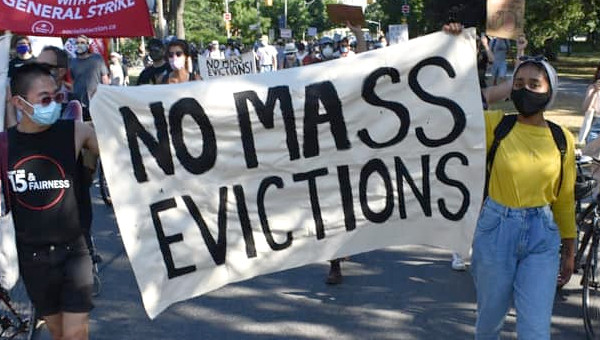

And this internal conservatism may well endure just as there is a nascent radicalization emerging in response to the crisis. We can point to labour’s challenge to reform Employment Insurance, spontaneous pickets and now plant occupations, and the anti-poverty agenda once so well managed by the McGuinty government has taken on a broad and popular life of its own. The New Democrats may well be bystanders or even worse a drag on pushing these forces further.

The socialist Left has a role even in this. Not through a practice of entryism but rather by presenting its own theoretical, organizational and cultural alternative. Recent public events sponsored by various socialist Left groups dealing with the economic crisis and the formation of the New Anti-capitalist party in France have drawn large audiences. There is clearly an appetite to understand what is happening in the economy through the lens of a Marxist political economy and how the Left is responding in organizational terms elsewhere. The ONDP is not going to engage in any of this in a formal manner but individual members are and will. •