Better Public Bus Service Is a Public Health Measure

A new COVID wave, a new round of service cuts to public transit. The reasoning always seems common sense enough: between remote working, things being closed down, and aversion to crowds, people are using the bus less.

The pandemic has no doubt posed a challenge to public transit, but it’s also been a giant missed opportunity to address multiple public health problems with an expansion of service. Transit regulators seem to think there is a set pool of bus users that can only shrink, never grow. But even during low ridership periods, most people are still traveling – it’s just by car. These are potential bus riders who have deemed the service too poor or unsafe to use instead of driving.

Cities designed for cars are neither affordable or accessible, but they also deny us any real choice in transportation – our public health is compromised as a result. Quality public transit means a service that, pandemic spike or not, people can use instead of a car to get around safely.

Omicron, Flu Season, and the Next Wave

The very measures transit agencies should, frankly, already have in place to improve service quality and accessibility would also enable better distancing and less exposure risk to COVID for riders and drivers.

Faster bus rides, made possible with dedicated lanes and traffic signal priority for buses, would mean shorter trips and less time spent in close quarters. Making trips more frequent, by adding buses to high demand and underserved routes, would avoid ‘sardine machines’ – packed buses where social distancing is out of the question. Eliminating fares would speed up routes by reducing boarding times and how long people wait inside and crowded outside buses; all-door boarding does the same while improving airflow. These are not hard to implement, and their success can be furthered with free N-95s for all bus riders and operators.

This is a lens we should have had even before the pandemic, but no one seemed to care about cold and flu season as we rode around on our morning commutes. We cannot keep reacting to airborne viruses as they pop up. There must be a baseline infrastructure that makes it possible to achieve limited exposure.

Climate Crisis

Better transit tackles the parallel public health crisis of climate change by making the bus a viable alternative to driving. This is essential to reduce the cardiovascular effects of pollution and curb the intensity of the climate disasters (wildfires, heatwaves, flooding, droughts) we’re seeing more and more of. More remote working has meant lower bus ridership, but transit agencies can attract those who still drive to work, school, errands, and appointments by making the bus safe and reliable enough for them to make the switch.

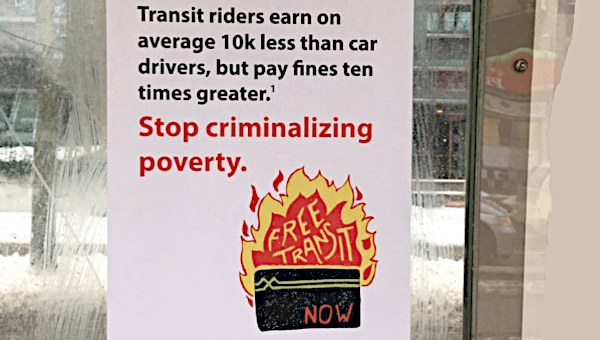

We are expected to stomach the heavy social costs and personal expenses of driving when it’s the only real way to get around quickly and on time. Making transit free, reliable, and easy to use is an investment in choice, access, and healthier cities.

But won’t attracting more people onto buses make them crowded all over again? It doesn’t have to. Say a route has a bus every 20 minutes and fifty people are packed in it at any given time as it crawls through traffic. If service frequency was increased so buses came every 4-5 minutes, you could triple the user pool over that 20-minute window and still have fewer people per bus (about 38 on each now). With a dedicated lane, the time spent together on the bus would also be shortened by at least 20%. More people, better served, in a safer way.

Road Safety

Fewer people go out when COVID cases spike, but others simply opt to drive and ride-share rather than risk public transit. This is unfortunate because more cars on the road is hardly a public health solution. Between poor air quality and the 2,000 annual deaths, and 130,000 injuries (9,000 ‘serious’) from road accidents in Canada, cars are quite adept at sending people to the hospital too.

It also ignores the safety of Uber and Lyft operators asked to bear higher contact risk with more passengers, receiving no employment benefits while doing so. We can prioritize good unionized jobs and affordable low carbon transport by expanding and improving transit service.

A Better Funding Model

The pandemic has exposed the folly of relying on fare-box revenue to maintain a public service. We can invest in the success of public transit with stable operational funding from upper levels of government and reallocation of existing local budget items. Cities and provinces spend billions of public dollars supporting cars through road and highway expansion, parking complexes, urban sprawl, and policing traffic. They can and must redirect these funds toward robust public transit systems that work for everyone.

COVID, climate crisis, and inaccessibility are the public health challenges of our time – political priorities must reflect that. •