Free Transit Movement Making Inroads

Late afternoon on December 9th, volunteers with the advocacy group Free Transit Ottawa stood near the doors of St. Laurent Shopping Centre, thrusting leaflets into the hands of people hurrying to catch a bus at the platform outside.

“Fare free now, fare free forever,” the leaflets demanded in bold letters.

The very idea of free public transit for all may seem bold, too, but most of the commuters who took time to stop and talk greeted it with enthusiasm. Having been granted a taste of fare-free service this month – a gesture of appreciation from the city for having endured one disruptive LRT (light rail transit) foul-up after another – the long-suffering public seems primed for some lasting relief.

For Free Transit Ottawa member Nick Grover, it’s an idea whose time has finally come. “One thing I’m heartened by is the fact that it doesn’t seem to be a fringe idea anymore,” Grover observed. “It’s starting to feel like this could actually happen here.”

Free Transit in over 100 Jurisdictions

According to advocates, some 100 jurisdictions around the world are currently experimenting with at least some form of fare-free bus, tram or train service in a bid to ease road congestion, reduce carbon emissions and make life more affordable for the low-income residents who form a sizable portion of the transit-riding population in most cities. They include Tallinn, Estonia, which introduced fare-free transit for registered residents in 2013, and Luxembourg, where riding a bus, tram or train has been free for everyone since March 2020.

In Canada, several cities have implemented more limited forms of fare-free public transit. In Calgary, a downtown portion of the C-Train is free to ride. BC Transit, which operates buses in Victoria and dozens of other communities in that province, allows unaccompanied children 12 and under to ride for free.

Free Transit Ottawa is hoping this city will be the first in Canada to go all the way, but the group is keenly aware of the roadblocks standing in the way, and the significant shift in thinking required to move them.

Reliance on Fare Box Revenue

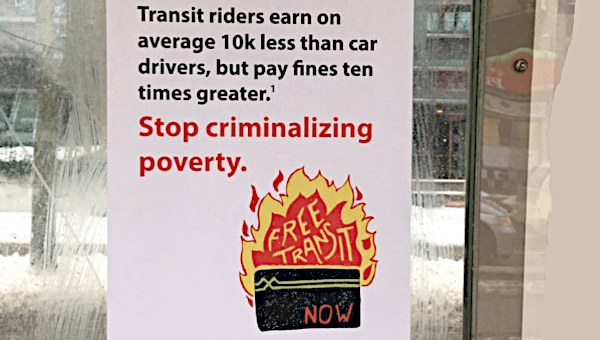

Like most North American cities, Ottawa relies on the fare box to fund a significant portion of its transit operations. Here, riders bore 55 per cent of the cost of running OC Transpo’s buses and trains, amounting to roughly $200-million a year before the pandemic drastically reduced ridership – and fare revenue. (The number crunchers at city hall call this the “farebox recovery rate.”)

Each year, the cost of riding OC Transpo – already among the highest in Canada – rises, and 2022 will be no exception, with fares set to increase by another 2.5 per cent in order to squeeze an extra $5.1-million out of riders’ wallets, money that will then be pumped back into the system.

The fare-free movement turns that funding model on its head. Advocates believe public transit, like other essential services, should have never been a user-pay system in the first place. After all, we aren’t charged a fee to drive down a city street, walk down a city sidewalk or sit in a city park. Our property taxes pay for those basic amenities.

As Montreal urban planner and social economy expert Jason Price, co-editor of the 2018 book Free Public Transit wrote: “We don’t pay for elevators, do we? And rightly so. The very idea is preposterous. Yet the public transit system plays the same role in the city, only sideways.”

Decision-makers in Ottawa have, in their own limited ways, already signalled they’re at least open to the principle of free public transit by offering it to certain select groups: Seniors ride for free two days a week, and the 2022 budget passed last week includes free transit passes for shelter clients.

“As a city, we are moving in a direction that people are starting to think, well gee, why do we have user fees for this, but not for things like libraries?” said Coun. Shawn Menard, who credits advocacy groups like Free Transit Ottawa for getting the conversation going.

“I think that the cause and case for [fare-free transit] is being made all over the world, and in our city now much more so than it was previously.”

Around the council table, however, free public transit remains a radical concept, Menard said. “There’s still a lot of resistance, and mostly that resistance is related to cost.”

Shifting Priorities

Advocates for free public transit say it doesn’t have to be that way. Rather, Grover explained, it’s a matter of moving the money around.

“We’re already spending the money on transportation, it’s just that the city is spending it on road-widening projects, developments that expand parking space, urban sprawl, and so these are all public dollars being spent to subsidize driving,” he said. “If we wanted to shift that to public transit, it would take a lot less money to do a lot of good to expand the service.”

Menard agrees that in the context of the larger city budget, it shouldn’t be hard to find the money. “That type of funding can be made up fairly quickly in a budget of $4.1-billion,” he said.

The city denied a CBC request last week to speak with chief financial officer Wendy Stephanson for this story.

There’s a broader movement afoot, led by the Federation of Canadian Municipalities and the Keep Transit Moving Coalition, to convince upper levels of government to do more to help cities fund their transit operations.

In Ontario, cities can already count on an annual gas tax rebate from the province. For Ottawa, that amounted to $38.5-million for 2020-21, though the pandemic threatens to erode that source, too. The city matches that provincial contribution through a transit levy of its own, which is set to increase next year.

(The city’s 2022 transit budget also relies on a one-time bailout of more than $60-million from the province to cover extra costs related to COVID-19.)

Last month, Ottawa’s transit commission passed a motion by Coun. Catherine McKenney to ask the federal government for operational funding “to reduce the user share of the cost of public transit so that we can reduce or eliminate user fees and encourage more transit use.”

“It’s not unprecedented to ask upper levels of government for permanent operational funding,” Grover pointed out. “There’s lots of options, there just needs to be the willingness. I think that’s what it always comes down to, is that political will.”

‘False Choice’ Feared

Some advocates fear even if the politicians find the will to reduce or eliminate Ottawa’s reliance on fare box revenue to run OC Transpo, they might compensate by diminishing service.

“The fare piece is absolutely important … but we also need a service that is frequent, reliable, and takes people where they need to go,” said Laura Shantz of the advocacy group Ottawa Transit Riders. “There’s a big fear that we’ll be given a false choice, a trade-off of, we’ll give you free transit but it’s going to be so terrible it won’t work.”

Such a system might be more equitable, Shantz said, but those commuters who have the choice are unlikely to get on board, even if it’s free.

“You wouldn’t want to just cut the budget and say, ‘OK now it’s free.’ You want high-quality service because that entices riders,” said Menard, who noted ridership in Ottawa has been dwindling steadily for about a decade. (The 2022 budget is predicated on a return to 82 per cent of pre-pandemic ridership levels, but many feel that’s unrealistic.)

The idea of free public transit has gained support from some unlikely corners. The Amalgamated Transit Union, which represents bus drivers and other OC Transpo employees in Ottawa, is a member of the Keep Transit Moving Coalition, while the Ottawa Sports and Entertainment Group has endorsed Menard’s idea for free shuttle buses on Bank Street to get people to and from events at Lansdowne Park.

Still, some free transit advocates find they can make inroads only when they water down their demands.

In Winnipeg, Coun. Vivian Santos has asked staff to report back on the feasibility of $1 bus fare after her push for free transit fizzled. “The biggest crux of the issue is money. Who’s going to pay for it?” Santos said. “In my mind it’s a no-brainer, but I think [for] the entire population who lives in suburbia … where everyone relies on vehicles, it’s harder to convince them.”

In Ottawa, Menard said he’s encountered resistance not only from council colleagues, but also from city staff who balked at the very word “free.” “There is some hesitation still, politically and otherwise,” he said.

To help sell the idea here, Free Transit Ottawa proposes starting with Ontario Works and Ontario Disability Support Program recipients before opening free transit to the general population. Grover believes the city is moving in the right direction, albeit more slowly than some would like. “There’s a sense that very slowly and very grudgingly, there is some movement,” he said. •

This article first published on the CBC News website.