Where is the ‘Recovery Fund’ to Save the Lives of Migrants?

There is a tendency on the part of the media and the political system to treat what is happening in the Mediterranean, and the issue of migration generally, as a separate topic in itself, usually describing it as an emergency (whether a security or humanitarian one – this makes little difference in terms of the logic of the discourse). For instance, no one would think to link this issue with the “recovery fund,” which is discussed in a completely different language and tone.

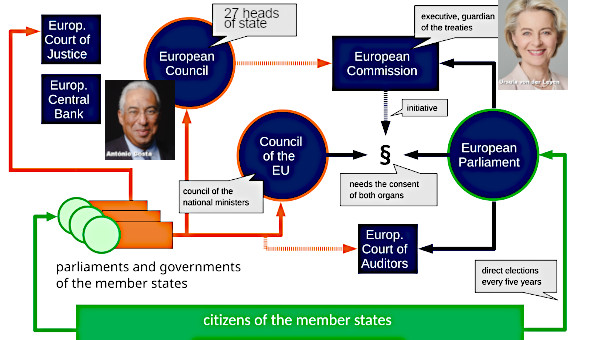

However, it seems to me that this attitude is deeply misleading. While the “recovery fund” marks a qualitative leap in the process of European integration (as to the direction, this remains to be established, of course), battles of fundamental importance are being waged in the Mediterranean for the definition of the borders of the Europe that is to be redeveloped – and therefore both for the quality of its citizenship and for its relations with the outside world, first and foremost with the countries on the southern shore of the Mediterranean, with the great Middle East and with Sub-Saharan Africa as a whole.

The shame of the Moria refugee camp and the shame of the detention camps in Libya are the most visible tips of the iceberg of a maritime border control regime that is, for all intents and purposes, a European one (let us be clear: without this fact representing any absolution of the responsibility of individual national governments, starting with the Italian one).

Most Lethal Border in the World

Of course, what happened with the tanker Etienne, owned by the Danish giant Maersk, was another emblematic scene for the interweaving of national and European responsibilities in a sea that has long become the most lethal border in the world. Indifference, cynicism, contempt for the elementary duty to save lives at sea, bodies left for weeks in a deplorable state, without any assistance: is this the Europe that wants to reinvent itself with the “recovery fund” after the shock of the pandemic? It would seem so, all the more if we bear in mind that it is not the “sovereignists” who are acting in the Mediterranean today, but governments such as the Italian one and Ursula von der Leyen’s Commission.

From this point of view, the intervention of the ship Mare Jonio on Friday, belonging to the Mediterranea platform, acquires a particularly major significance. Quite simply, the Mediterranea volunteers did what the Maltese and European authorities should have done: they boarded the ship, provided initial medical assistance to the 27 refugees and migrants rescued by the Danish vessels and immediately noted the presence of an unsustainable situation. The result was the decision to transfer the 27 to the Mare Jonio.

But more generally, one cannot escape the conclusion that the intervention conducted by Mediterranea has prefigured a different way of managing the maritime border in the Mediterranean, opening a “humanitarian corridor” from the grassroots level and offering a powerful symbol of the construction of another Europe through activism at sea and on the borders.

Activism at Sea

This activism has been strengthened in recent months, and at the same time has been at least partially transformed. The construction of a real “civil fleet,” for which Alarm Phone serves as the coordination center for rescues (a step toward the establishment of a real “civil MRCC” – Maritime Rescue Coordination Center), has led to a deepening of the immediately European dimension of the operations at sea, while in Germany in particular – as Sebastiano Canetta recounted in this newspaper on Friday – a movement has grown that accompanies these operations on land, involving highly heterogeneous actors (from churches to municipalities such as Berlin and some Land authorities).

For this form of activism at sea, it is more and more clear that what is at stake today is the struggle for a Europe different from that defined by the shame of Moria, Libya and the Etienne, starting from a new way of narrating migrations and linking them to the social mobilizations that are taking place in the context of the pandemic. In addition, partly because of the great impact garnered by the Black Lives Matter initiatives in the US, which are also changing the grammar of antiracism in Europe, the traditional languages of humanitarianism are being displaced, or in any case broadly modified. In particular, the recognition of the central role and struggles of refugees and migrants, including in very harsh conditions, such as the crossing of the maritime border in the Mediterranean, is a feature that characterizes activism at sea to an increasing extent.

The maturity of the cooperation between different actors within the “civil fleet” is an extraordinary example of action on the immediately European ground, one that other movements could take up and develop further. The resonances between the activism in the Mediterranean and the mobilizations in the United States is another aspect that would certainly be worth exploring.

More generally, activism at sea today offers us, in terms that are partly new, the actualization of a radical politics of borders and migration, without which it would be truly difficult to revive reflection and initiatives regarding the European question. With its operation on Friday, Mediterranea gave a great example of this radical politics, starting from the elementary need to provide assistance to 27 refugees and migrants abandoned by Europe. •

This article first published on the Il Manifesto Global website.