‘A Radical Turning Point’? Democracy in Honduras

Twelve years after the coup against Manuel Zelaya, the Honduran people are regaining hope. With her overwhelming victory in the November 28 general elections, Xiomara Castro, Zelaya’s wife and the first woman to be elected president, now has the chance to lead the country out of the nightmare of Juan Orlando Hernández’s narco-dictatorship.

Claudia Fanti talked about these events with historian Pedro Landa, a human rights and environmental advocate.

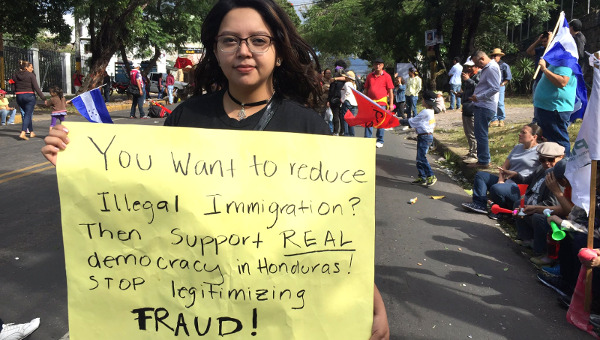

Claudia Fanti (CF): After the fraud in the previous elections, how do you explain Xiomara Castro’s victory?

Pedro Landa (PL): The result was in the air because discontent with the Partido Nacional was widespread. But no one expected such a clear advantage: Xiomara Castro’s victory was so overwhelming that the government had no chance to manipulate the results. There were various reasons for that. With so many officials and former government officials tied to organized crime and drug trafficking and appearing in the Pandora Papers, the Panama Papers, and the Engel List (which collects the names of 55 Central American officials accused by the US of various crimes), the people have grown tired of being ruled by a narco-dictatorship.

In addition, there were the repeated corruption scandals, the poor management of the pandemic, and the ineptitude shown by the government in the face of the emergency caused by hurricanes Eta and Iota in 2020. Finally, there has been a progressive erosion of human rights and civil guarantees in the name of promoting investment, in the framework of a highly extractive-focused policy culminating in the law on the Zones of Employment and Economic Development (ZEDE), or model cities, designed to sell off the country’s territory and national sovereignty. This law is so unpopular that more than 200 municipalities out of 298 have declared themselves ZEDE-free, many of them governed by the Partido Nacional itself.

CF: What are the main challenges facing the new government?

PL: The first step should be the repeal of laws such as those on ZEDEs and mining, the reform of the penal code, and the repeal of decrees granting immunity to public officials, the police and the army. As well as adherence to the Escazú Agreement, together with a law guaranteeing indigenous peoples the right to decide regarding their territories. More generally, the challenge is to move past the current project for the country, oriented toward attracting investment through the exploitation of human and natural capital, in the direction of a sustainable and inclusive development model, centered on fiscal equity, priority for social spending, and the demilitarization of the country.

And it is essential to promote a social pact that would translate into a new Constitution, capable of including the excluded, impoverished, and socially and judicially criminalized sectors, launching a national dialogue that would lay the foundations for a change in institutions and the economic model. In this sense, Xiomara Castro could truly mark a radical turning point in the democratic history of Honduras: we hope that, with the support of the people, she will be up to the challenge to lead the country on a different path from the one that has been followed in the last 12 years.

CF: Zelaya’s intention to call a referendum for a Constituent Assembly was one of the reasons for the coup against him. Will it be possible to accomplish this project this time?

PL: More than possible – it is necessary. Because the current Constitution has been modified and arbitrarily interpreted to such an extent that it has lost much of its value as a social compact. On the other hand, the current climate is different from that of 2008-2009, and the specter of “communism” stirred up by the Partido Nacional no longer scares anyone. Even more, the creation of a new Constitution was part of the recommendations put out by the Truth and Reconciliation Commission after the coup.

CF: Honduras is one of the most dangerous countries for defenders of the environment. What measures should be taken with regard to the environment?

PL: The violence and criminalization to which environmental defenders are exposed can be traced back to the extractivist policy promoted since 1998, and which has become increasingly aggressive since the coup d’état. Consequently, in order to reduce the pressure on activists and on nature – Honduras is one of the countries most vulnerable to climate change in the world – it is necessary to curb extractivism and create a genuine environmental agenda in line with the reality of the country and the entire planet, promoting a comprehensive reform of the development model that would incorporate, among other things, the principle of corporate social responsibility, with the human rights obligations that come with it, and adherence to the Escazú Agreement, with the corresponding regulatory and institutional reforms. •

This article first published on the Il Manifesto website.