Canada: No Change

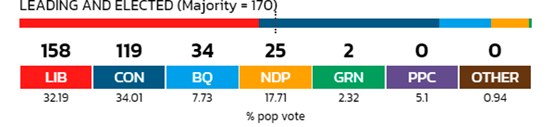

Canada’s Liberal Party prime minister Justin Trudeau has managed to get re-elected for the third time in the snap general election he called. The Liberals won or were leading in 158 seats (one more than their 2109 results), out of a total of 338 seats, and the Conservatives trailed the Liberals, winning or leading in 119 seats, three less than their 2019 result. But Trudeau will fall short of an outright majority in parliament (as before) and will need the support of the left-leaning New Democrats (25 seats) to get any legislation through.

Indeed, the result is more or less the same as in the last election two years ago. Trudeau’s plan to get a majority based on the ‘success’ of the government’s handling of the COVID crisis backfired. Many voters considered the election as a cynical move and a waste of time. Indeed, it was the Conservatives who got the biggest vote (as in 2019) attracting 34 per cent support to the Liberals’ 32 per cent, but Liberal support is centred around urban and suburban areas where there are more seats. And Canada has a first past the post system as in the UK.

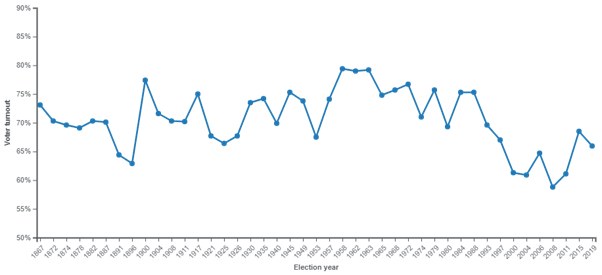

Voter turnout has been slipping in the 21st century from a peak of 75%; in this election it was around 65% – much higher than the US, about the same as the UK but below other G7 economies like Germany and Japan. A 65% turnout means that the ‘no vote’ party was the largest – and Trudeau’s Liberals attracted just one in five potential voters.

Canada: voter turnout (%)

As the smallest G7 country in GDP and population, Canada has seen far fewer COVID cases and deaths than many other countries, and Trudeau recently reopened the border, but only to the vaccinated. In the election Trudeau pointed out the dire situation in Alberta, run by a Conservative provincial government, which refused to adopt social distancing restrictions and now has a wave of cases and hospitalisations. Interestingly, the anti-vacc extreme right-wing People’s Party failed to make a mark, polling only 5.1%.

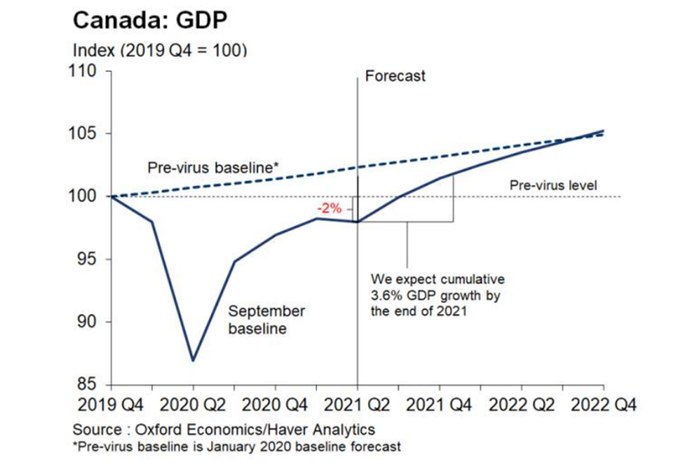

Trudeau may be back in office, but like the other G7 economies, things are not rosy economically. Canada’s 2021 economic outlook is similar to that of other developed countries. After the largest economic contraction since 1945 (a dip of 5.5% of GDP in 2020), Canada is still in recession, according to the latest figures, although forecasters (Oxford Economics) are still expecting a sharp recovery.

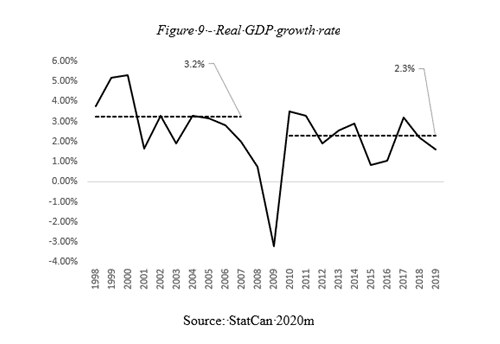

Even if the above forecast turns out to be correct (and that is uncertain), the long-term economic trends for the Canadian economy are not great. A recent Macdonald-Laurier Institute report, wrote that Canadian “real GDP growth over the past decade has been as lethargic as the decade after the onset of the Great Depression in 1929” (Cross 2020). Thus, Canadian capitalism had already been experiencing problems for over a decade when the COVID-19 lockdown started.

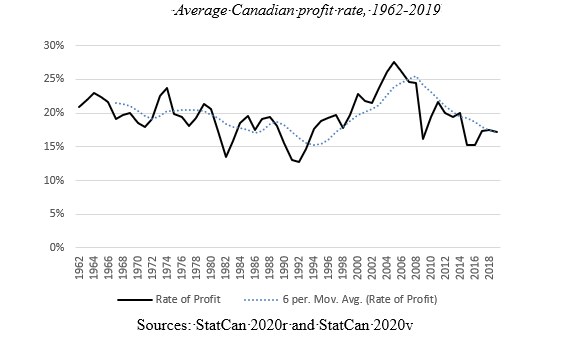

Economic Stagnation

For an account of Canadian capitalism up to the 1990s, I recommend the work of Marxist economist, Murray Smith. For the recent period, Geoff McCormack of the Centre for Canadian Studies at Guangdong University for Foreign Studies has produced an excellent analysis of Canadian capitalism, which I draw upon here. McCormack finds that in the 13-year period following the ‘Great Canadian Slump’ of 1990-92, the profit rate on Canadian capital rose from 13% to 28%. But after peaking in 2005, it began to fall, reaching 17% in 2019.

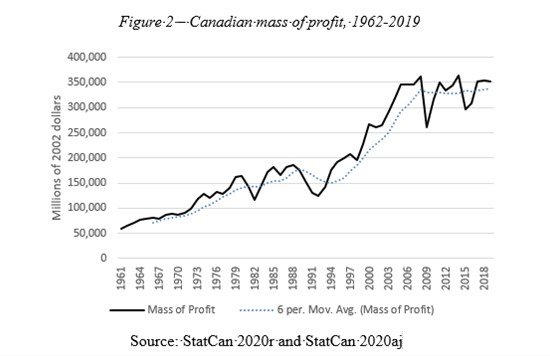

The downward trajectory of the profit rate during this 14-year period was accompanied by a stagnating mass of profit. Between the years 1993 and 2005, the mass of profit grew by 142%. After 2005 and until 2019, however, it stagnated, having grown by merely 1.5% over the entire period.

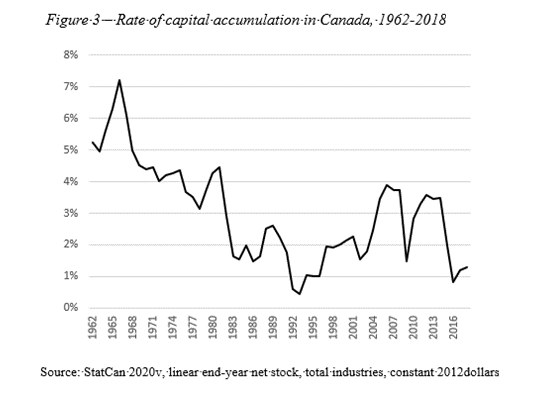

Canada did escape much of the impact from the global financial crisis of 2008-09 because of the long period of relatively strong profitability and capital accumulation preceding the crisis. But by 2006, according to McCormack, profitability had begun to erode. “Afterwards, ‘sneaking’ stagnation became increasingly evident in rates of capital accumulation, capacity utilization, employment, as well as real wage and GDP growth.”

In the eight years following 2010, business investment in plant and machinery grew by an average of only 0.1%. Recovery after the Great Recession was driven a credit-fuelled boom in housing. People got jobs but at low rates of pay, just as in other G7 economies. In the years following the Great Recession, real wage growth slowed substantially, averaging just 0.4% per year. As McCormack says, “given poor profitability, lacklustre capital accumulation, truncated capacity utilization, low employment and low real wage growth, it is unsurprising that real GDP growth, too, was weak.”

Canada increasingly relies on its production of oil and gas and other mineral resources. And so there is no drive to phase out fossil fuel production to save the planet. Trudeau put it in a speech to cheering Texas oilmen a couple of years ago: “No country would find 173 billion barrels of oil in the ground and leave them there.” So Canada, which is 0.5% of the planet’s population, plans to use up nearly a third of the planet’s remaining carbon budget. There’s oil in the ground and it must come out.

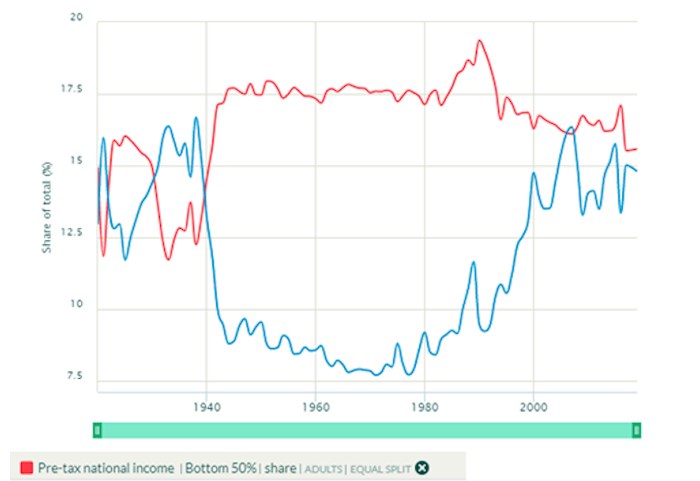

And even the growth in incomes in the last decade was not shared equally. As in other OECD economies, the share of income going to the top 1% of ‘earners’ rocketed while the share going to the bottom 50% fell. Indeed, the top 1% has nearly as much income as the bottom 50%!

Canada: top 1% share (blue); bottom 50% (red) – World Inequality Database.

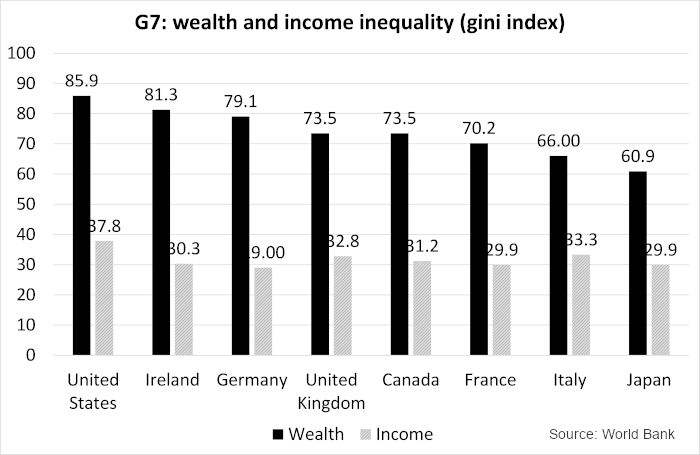

And wealth inequality in Canada is on a par with other G7 economies.

So the decade since 2009 has been characterized by sneaking stagnation, rooted in profitability problems that began after 2005. This has manifested itself in the stagnant accumulation of machinery and equipment, low industrial capacity utilization rates, low employment levels, as well as low real wage and GDP growth. It is an expression of what I have called the Long Depression that all the major capitalist economies have sunk into since 2009 in the ten years leading up to the COVID slump.

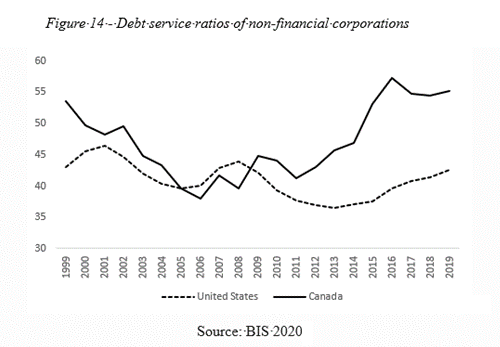

And just as in other major G7 economies, corporate and household debt has jumped to record highs. Despite very low interest rates, Canada’s corporate sector is weighed down by debt service costs. In 2020, 55% of corporate income went to paying interest and principal payments on loans, whereas it amounted to 43% in the US. The debt service ratio increased from 38% in 2006 to 57% in 2019 as economic stagnation wore on business balance sheets.

The Bank of Canada economists have classified 25% of Canada’s publicly traded companies as zombie firms i.e. they persistently do not earn enough revenue to cover interest payments on their outstanding debts.

So Canadian capitalism bears all the hallmarks of the contradictions facing the rest of the G7 economies as they come out of the COVID slump. Prime Minister Trudeau achieved nothing with his snap election and faces the same problems in getting Canada’s capitalist economy going as before. •

This article first published on the The Next Recession website.