This May Day Even the Designation ‘Workers’ is Under Threat

Whenever it seems that corporations have gone as far as they can in expressing their disdain for workers and any degree of worker autonomy, they manage to come up with something still more outrageous. As mind-boggling as it may seem, a group of high-tech companies now want to rob workers of even their identities as workers.

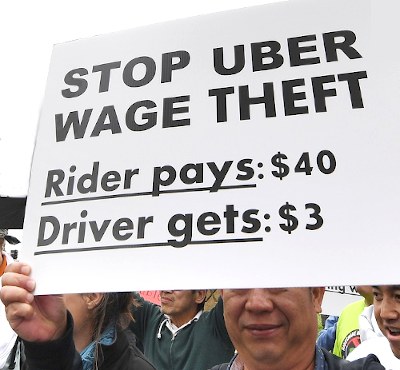

The latest threat involves the ride-hailing company Uber. Uber is in the midst of an international campaign – enthusiastically and richly supported by the likes of Lyft, DoorDash and Amazon – to legally classify those who they hire and fire, whose working conditions they set and monitor, and whose pay they determine, as not really workers but dependent contractors. If successful, this would, for a start, mean that these ‘non-workers’ would be excluded from minimum standards on wages, vacation pay, parental leave, workers’ comp, unemployment insurance.

But that is not the big prize for Uber. Uber’s real trophy lies in blocking their drivers from even trying to form a legally recognized union by redefining them as non-workers, even though it would be difficult enough, given the nature of the job and Uber’s single-minded obsession with complete control, to unionize Uber’s drivers and win first contracts without this added hurdle. But for Uber, every measure that obstructs its drivers from having a collective, independent voice is worth all the money they are spending on lobbying to reclassify them. In California alone, Uber and its allies spent $220-million on a public referendum to – successfully – reverse an earlier decision unfavourable to the gigdom lords.

Such corporate aggressiveness generally leads to two kinds of responses from organized labour: reassert union principles and stubbornly struggle on, or – in the face of an accumulation of defeats – retreat into an accommodation with and ultimate acceptance of the so-called ‘new realities’. Given the choice, our sympathies would of course lie with those at least trying to hang on to basic principles and soldier on, against those who, in the name of being sober and hard-headed, ignore the well-travelled costs of surrendering principles and fading from the struggle.

Yet neither response is adequate to what the working class now faces. Is there another option, one that acknowledges the limits of past strategies but is not ready to more or less give up? In looking to come to grips with this challenge, we begin with a brief elaboration of the Uber initiative. (See Jane McAlevey’s excellent overview in The Nation.) We then turn to the reaction to Uber of Jerry Dias, the head of Unifor, Canada’s largest private sector union. Dias has been the main Canadian proponent of accommodating Uber. The last section poses what a credible alternative might entail.

Sectoral Bargaining Uber-style

The union and public outrage against Uber’s vile arrogance forced Uber to take a breath before returning with a more ‘sophisticated’ approach to getting to the very same place. That approach involves ‘sectoral bargaining’ Uber-style and finding some union(s) to entice to join their scheme.

There is some history to sectoral bargaining in Canada especially in Quebec (discussions on sectoral bargaining in Ontario and British Columbia have taken place since the 1990s but gone nowhere). The Quebec legislation goes back to 1934. It was driven by the concern, in sectors where a significant part of an industry was unionized, to limit unfair competition from non-unionized workplaces. The law allowed the Minister of Labour to extend the application of collective agreements in specific industrial and geographic sectors to all workers employed there. Over the years, and since the mid-1990s in particular, the act was significantly eroded and is now largely dormant (see Eric Tucker, Great Expectations, p.122).

The idea of bargaining across individual employers has some obvious appeal, and positive historical examples of particular forms of sectoral bargaining do exist. But the flaws in its mechanisms are well-known. A letter signed by prominent American labour academics and activists explains the limits as well as the historical and legal background of ‘sectoral bargaining’ in the US. As instituted, sectoral bargaining was top-down and didn’t address the imbalance of power within each workplace, and so had no impact on health and safety, speed-up, and management abuse. Countering this would have required real worker participation. Without it, the process didn’t build worker power either in the workplace, sector or in the province/country as a whole.

In Uber’s hands, those flaws in sectoral bargaining reach a new plane. If those who do the work are accepted as dependent contractors, Uber has declared that it is open to some minimum standards and flexible individual benefit packages – at unspecified levels. But the sectoral bargaining it offers stands outside of any union relationship and thus of workers bargaining with the company. This means that a collective worker voice for defining flexibility is excluded. In its place is an agreement between Uber and a union it chooses to ‘represent’ the ‘non-workers’ in exchange for a ‘service’ payment for doing so.

Throughout its history, the labour movement demanded the replacement of ‘Collective Begging’ with ‘Collective Bargaining’. Uber, priding itself on being forward-looking, offers a return to that patronizing past. Uber’s proposal offers workers no choice on who speaks for them; no shop-floor representation to address working conditions; no say in what the priorities of the negotiations will be; no ratification of what the non-union negotiates on their behalf; and, of course, no strike threat if the non-workers don’t like the deal the non-union ‘negotiated’ for them. In short, no independence from Uber and no collective powers for workers.

Unions that go along with Uber’s contemptible ploy would set a precedent – even if inadvertently – for spreading it into other sectors (which is a good part of why Uber’s corporate and political allies have been so supportive of their strategy). In the US, the Teamsters flirted with such participation but soon reversed their position. The IAMAW (International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers) set up the Independent Driver’s Guild as its front, which Uber subsequently recognized as an ‘association’. Even with this, an example of what the Guild is up against is expressed by the Guild’s executive director: “It took more than two years for us to win our fight for a minimum wage and only a couple months for the apps to find a way to skirt the rules by manipulating driver access to the apps.”

The Dias Accommodation

When Uber recently brought its campaign to Canada, the leader of Canada’s largest private sector union, Unifor, quickly announced that though he certainly considers Uber’s workforce to be ‘workers’, he is nevertheless having ‘preliminary discussions’ with Uber that leave aside the question of classifying workers as dependent contractors. “I’d rather try to find a way,” Jerry Dias defiantly asserts, “to build on the concept of unionization.” It is hard to understand how core principles of unionization can be defended and built on by setting aside their very foundation: a belief in the potential power of workers, the right to independent representation, and the importance of struggle for workplace democracy so as to build workers’ power.

Dias seems, in this regard, ready to sabotage another union principle – solidarity. He appears unbothered that his words and actions might undermine unions in Canada and elsewhere who are trying to organize Uber drivers into legitimate unions. The reaction from others in the labour movement – especially from those already engaged in organizing Uber workers – has been quick. Jan Simpson, the head of the Canadian Union of Postal Workers (CUPW), expressed the sense of betrayal: “We reject all forms of unionism that don’t put the workers at the centre of struggle… Backroom deals with employers take away workers’ power and put it in the hands of bureaucrats and bosses, but real unions are not here to do the bosses’ dirty work. We are here to organize with workers for a better future.”

This is not the first time that Dias has placed himself on the pedestal of being proactive and practical while anyone who disagrees accused of living in ‘la-la land’. It’s therefore worth a closer look at similar prior ventures to skirt union organizing struggles as case studies to assess how substituting pragmatism for union principles pans out.

In 2007 the CAW (the Canadian Auto Workers now Unifor) made an agreement with Magna that would give the union access to Magna’s workers in exchange for a rather strange union presence. As with the Uber program, the deal was not voted on by the workers. It did not include bargaining over wages (they would be set by trends in the average industrial wage) or pensions (as Magna had its own savings plan in mind). It did not include elected union stewards and so could not promise to build the union over time. And it committed to a no-strike pledge – not temporarily but forever. The “Framework for Fairness,” as it was called, couldn’t be amended and workers’ collective rights could not be modified (meaning it could not be improved).

Dias, then an Assistant to the President of the CAW, was made the point man in dealing with Magna. The deal eventually delivered nothing; the workers had little interest in the Framework and Magna saw no pressure to continue to bother with this experiment. When Dias became president of the union in 2013, he declared the Magna deal a failure and dropped any pretence of working with Magna.

In 2016, as president of the union, Dias sold an agreement to General Motor’s Oshawa workforce with the promise that in exchange for two-tier wages and benefits (new workers to be hired at lower wages and excluded from the defined benefit plan), GM would keep the plant running. A year into the reluctantly-accepted agreement, GM announced that it had changed its mind. Knowing how weak the language was, the union did not even bother to arbitrate that decision. GM withdrew its promised investment, but the concessions of course stayed in place. The damage went beyond losses in wages and benefits. The experience left young workers – often touted as the future of the union – alienated and cynical in being treated as second class members in their own union, a bad sign for hopes of union renewal.

GM later reversed itself in January 2021 and announced a new investment in Oshawa of uncertain duration and of uncertain employment commitments. This could hardly be credited to pressures coming from Unifor – such pressures were modest at best once the product was gone and the closure seemed certain – but was rather due to changes in markets and internal corporate strategy. The jobs were welcomed in the Oshawa community but since the former workforce had separated from GM after the closure, GM’s workforce would now be paid the lower compensation paid to ‘new’ workers. It is still unclear if workers in GM’s former supplier plants in Oshawa will still have work or if GM will source the work elsewhere.

Shortly after the GM negotiations, Dias turned his attention to the explosion of Airbnb rentals in Toronto. Other unions were already involved in the issue. The largest hotel union local in the city was in the midst of trying to regulate and limit Airbnb, working through a coalition – named fairbnb.ca – that included tenant’s rights organizations. The concern was that hotel workers’ jobs were threatened and the increased use of Airbnbs by landlords and condo owners was further limiting the availability of rental housing.

Dias’ sudden intervention in support of Airbnb surprised even some of the hotel workers in his own union. As with Uber, the obvious agenda was that in exchange for legitimating the company, Dias could position himself to the cheap and quick recruitment of the corporation’s cleaners. In a letter to Toronto Mayor John Tory (a version also sent to the Vancouver mayor), Dias praised Airbnb for “setting an example for a path forward that couples the potential of the digital economy with the reality of working people across the country.” Wandering further, he explained that “Because of Airbnb’s progressive approach, Unifor is exploring ways to work together with them… [and] to explore areas of mutual interest to improve the public good, and if possible, work toward a national partnership.”

In addition to undermining the coalition challenging Airbnb, it was not at all clear that Dias’s strategy for extending unionization among Airbnb workers had been worked out. Steve Tufts, a York University geographer and labour activist following this sector closely, noted that “it is difficult to see how large numbers of new members might be organized through this strategy and whether any partnership with Airbnb will give Unifor any leverage in reaching these precarious workers.” The initiative quietly faded away and again the main outcome was the further isolation of Unifor and its members from the wider union movement.

There were other embarrassing endeavours like the farcical raid on the Toronto local of the ATU (Amalgamated Transit Union), but in no case did Dias seem to learn anything from the experience. Equally distressing however, is that neither did the members of the union act as a check on his direction. There were certainly private grumblings, but the members never took on the crucial responsibility of directly challenging a leader gone astray. That has been extremely costly for both the union and the labour movement as a whole.

Toward an Alternative

The repeated acts of desperation by union leaders like Dias reflect a very real crisis in labour and a sense of the inadequacy of the movement’s current trajectory. If alternatives that are top down and opportunistic – misguided fixes that have no respect for the actual potential of working people (indeed the potential is often denigrated by leadership that should be encouraging it) – what then can we offer in their place?

Four considerations seem crucial. First, spreading unionization starts with what we’re doing within each of our unions. If unions are accepting concessions without a fight, that’s hardly solid ground for increasing the interest of non-union workers in joining the union. If unionized workers can’t or won’t stand up to the power of employers, why would non-union workers join? Our failures aren’t secret; the companies we’re trying to unionize will be sure to spread any negative news. Nor is it likely that union members frustrated with their own conditions will take kindly to the union spending a great deal of energy and resources on recruiting workers in other sectors.

Second, sustaining support for unionization drives demands a higher cause. When the spread of unionization is reduced to increasing the union’s dues, we are doomed. A business style cost/benefit analysis is likely to conclude that organizing low paid workers, who won’t pay much in dues but will likely cost a lot to service properly, isn’t a priority ‘investment’. The union may be sympathetic or have the occasional union drive, but left to such narrow arguments, the deep commitments required to challenge the employer’s hold on workers will simply not be there.

Expanding unionization must be understood as part of the larger project of class solidarity and unity. Unless we’re bringing the standards of others up, unionized workers will – as we’ve all witnessed – be isolated and ultimately see their own standards reduced. There was a time when some unions might have gone it alone and succeeded. But we have been beaten up enough over past decades to learn that unless we overcome the fragmentation and divisions among workers, we all remain vulnerable. In this regard, Uber drivers, food delivery workers on bikes, low-paid temp workers, and gig economy workers of all kinds are part of the same class with the same ultimate interests as auto, hotel, food, and public sector workers. And these common interests includes the currently unemployed. Divided, we can’t shift the balance of power in society from the major corporations and employers of all sizes to workers.

Third, and this follows directly from the above, the best practices for organizing workplaces are unlikely to be implemented without a radical transformation in the ideology of unions, their structures and their everyday functioning. Implementing the best organizing strategies raises the broadest questions about how unions determine their priorities and how they relate to their members; what kind of education unions run and the extent and depth of members’ participation; the role of staff and how they are trained; the union-community nexus; and the degree to which its members, and not just specialized staff, play a critical role in the labour-intensive work of reaching other workers.

Crucially, support for best practices demands union leaders who welcome rather than fear the emergence of new leaders, higher expectations, and greater participation and challenges from below. A culture of passive acceptance of the pronouncements of labour leaders damages and often destroys the critical and creative life inside the union. Such critical activism in unions – fractious and messy as it may at times be – is fundamental to grappling with what we face and to how the union movement can be reborn.

Fourth, the scale of what we are up against in fighting the Ubers and Amazons of ‘digital capitalism’ would seem to demand a radical change in the relationships among unions. It is difficult to imagine that local struggles, as essential as they clearly are, can fully unionize and win decent contracts from these mammoth corporations without a concerted response from unions as a whole. In the 1930s, unionized American mineworkers recognized that if other key sectors weren’t unionized, mineworkers would ultimately be isolated and weakened. They consequently sent out some hundred members (with only their expenses paid) to help organize the steel industry. The revival of the labour movement rests on that kind of sensibility and understanding, with its shift of threats into opportunities, and spirit of organizing as no less than a crusade to change the world.

There is also a psychological factor involved here. The greatest antidote to complaints about the demoralization and passivity of workers lies in workers being inspired by the formerly fragmented and largely ineffective movement coming together to develop credible plans, choose clear targets, pooling financial resources, and committing its best researchers, communicators and organizers to winning campaigns and struggles.

Conclusion: Getting Beyond Uber and the Union Impasse

Uber is the stalking horse for a new – if in other senses really old – form of undermining worker organization and union independence. Obscured by appeals to the desire for flexibility, false independence and the ‘inevitability’ of digital platforms, the reality reflects more traditional goals of corporations and employers: low wages, no worker control over their jobs, job insecurity, work intensification, and no ability to collectively organize to resist. This is not the future we want for ourselves, our children, our neighbours and their kids, and all those who sell their labour-power to make a living. That Canada’s largest private sector union has essentially endorsed Uber’s initiative makes dealing with the difficult organizational terrain we need to build on all the harder.

If there is a clear message that comes out of the recent decades of rising inequalities, permanent working-class insecurities, and ever narrower democracy, it’s that we don’t have the option of standing still. If we don’t challenge the anti-union corporate strategies of Uber (or Amazon or Google or Walmart for that matter), we’re essentially inviting them to go further and rain more hell down on the Canadian and international working-class. Absent a sense of thinking broader and bigger, expectations tend to fall, commitments stagnate, the confidence in taking on risky struggles falter.

At its roots the question of stronger and more effective unions goes beyond unions to the need to build the working-class. Capitalism has left workers fragmented, dependent on their employers, and short-term and individually oriented in the face of the survival pressures confronting workers and their families. The great challenge – the challenge of socialism – is how to remake the working-class that capitalism has so shaped to fit its needs into a working-class with the vision, coherence, confidence, commitment, understandings and organizing skills to show that the present we find ourselves in is not the best we can achieve. •