Brazil After the Collapse

Health experts warned about it for weeks. In early March, the Brazilian health system entered a state of collapse under the weight of a nationwide spike in COVID-19 infections. Hospitals were not able to attend to all patients who needed treatment. By the end of March, all over Brazil, more than 6000 people were waiting for an ICU bed, most of them in overcrowded health centres and emergency wards without the necessary equipment and personnel for treatment.

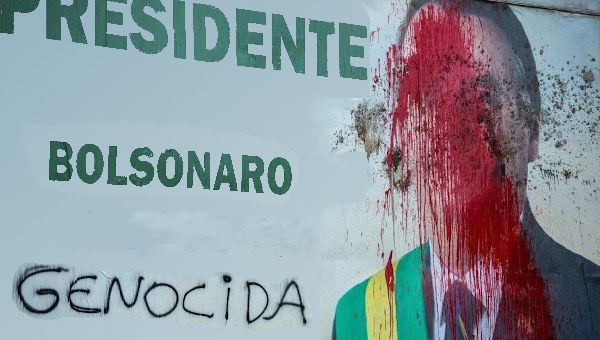

In parallel, the power bases of the presidency of Jair Bolsonaro eroded in rapid fashion after he seemed to have consolidated his power in early February with the election of his preferred candidates to the powerful positions of speaker of the Parliament and of the Senate.

The year began with the collapse of the health systems in the states of Amazonas and Roraima in the north of Brazil where the new and more contagious P1 variant of the Coronavirus originated. The minister of health Eduardo Pazuello received warnings at the end of December 2020 that oxygen supply shortages in the state of Amazonas might occur by mid-January, but he only acted when this lack inevitably led to numerous deaths on January 11 in the capital city Manaus. In the first days of January, instead of oxygen, he sent thousands of doses of the anti-malaria drug Chloroquine to Manaus, which has no proven efficacy against COVID-19.

Alarm Bells and Warnings Ignored

The extraordinary increase in infection rates and deaths in the state of Amazonas rang alarm bells with health experts around the country, but the federal government ignored all warnings. Instead, in the midst of a decrease in popularity due to the health crisis, Bolsonaro landed a coup with the elections for the speaker of the Parliament and of the Senate in early February. Moderate candidates in opposition to Bolsonaro were the initial favourites for these elections, but Bolsonaro distributed millions of Reals (R$) to municipalities beforehand, and his two candidates won both posts: Rodrigo Pacheco from the Democrats party for the Senate and Arturo Lima from the Progressistas party for the Parliament.

This manoeuvre allowed the Bolsonaro government to forge a closer relationship to the parties of the Centrão (a grouping of clientelistic centrist politicians) as the basis for its legislative projects, since the government does not command a majority of its own. The election of the speakers to the Parliament and Senate also led to a split in the two centre-right parties, the Democrats and the PSDB (Brazilian Social Democracy Party), who were planning to field their own candidates for the presidential elections in 2022. Nevertheless, about half the parliamentary delegates of each party aligned with the Bolsonaro government for the elections, leading to infighting within both parties. The earlier president of the Parliament Rodrigo Maia even left his party, the Democrats, as a consequence.

Polishing Up Bolsonaro

The offer that Pacheco and Lima made to Bolsonaro was designed to organize majorities for the legislative agendas of the federal government in exchange for policies with a wider appeal that both politicians could sell to their constituencies. This arrangement would have served Bolsonaro in the form of a more stable power base in Parliament and society, and a professionalization of government policy making. It would have also served Pacheco and Lima in their role of domesticating Bolsonaro, demonstrating their leadership potential, since both politicians plan to stick around Brazilian politics for a while yet. In other words, this arrangement was perfect in helping Bolsonaro regain societal confidence and paving his way to re-election in 2022.

Yet the arrangement did not hold because the person who would have most profited from it stuck to his erratic form of politics, and ended up in political isolation: Jair Messias Bolsonaro. At the centre of the increasing isolation is his unwillingness to publicly agree to the most obvious measures to contain the COVID-19 pandemic: lockdowns, curfews, social isolation, and the wearing of masks. This has led to enormous frustration and anguish in the army, and in the corporate sector, which finally understood that any prolongation of an uncontrolled pandemic will hurt profits.

Corporate Disaffection and Diesel Fumes

But there was a second reason why the corporate world fell out with Bolsonaro, culminating in a letter from 300 corporate leaders and economists, published on March 22, calling for a national policy to fight the pandemic based on science. The letter was signed by four former finance ministers, five former presidents of the Brazilian Central Bank and the national development bank BNDES, the two co-chairs of the largest private bank Itáu Unibanco, and the president of Credit Suisse in Brazil.

The letter, symbolising deep dissatisfaction in the corporate and financial world with the president, was preceded by the removal of the market-friendly president of the state-owned oil company Petrobras by Bolsonaro on February 19. Petrobras was at the center of the removal of Dilma Rousseff from her presidency and the criminal conviction against former president Lula. The decisive power struggle between the social-democratic Workers Party (PT) and the centre-right was always about the strategy around Petrobras, which commands very advanced exploration technology and has access to one of the largest oil fields on the globe, discovered in the 2000s.

The struggle centers around two alternate strategies. First, the PT’s strategy aims at a national developmentalist strategy with some amount of control over petrol prices for national consumers, both corporate and private. In contrast, the center-right strategy is focused on allowing oil giants from Europe and the US to access oilfields in Brazilian waters, privatizing Petrobras, and permitting petrol prices to closely align with world market prices. Both strategies represent the classic alternatives between a national bourgeoisie trying to establish itself on the world market with the addition of a specific national strategy, turning itself into a sub-imperialist power in Latin America, and the strategy of the comprador bourgeoisie that is immediately subservient to capitalists in Europe and North America.

At the start of February, Brazilian truckers, who were long seen as allies of Bolsonaro, became increasingly frustrated with his government and threatened a large strike in response to increases in the price of diesel. The strike failed to materialize due to disunity among truckers, but it, nonetheless, led Bolsonaro to reconsider pricing policy at Petrobras. He intervened in the company and replaced market-friendly Roberto Castello Branco with an army general. At present, it is unclear if there will be a pricing policy change at Petrobras or how it will look, but the audacity of government intervention with regard to this embattled oil giant was enough for a serious fallout between the corporate world and Bolsonaro.

Head in the COVID-19 Sand

The escalating health crisis and the dwindling of support for Bolsonaro among corporate and financial elites has led to a rearrangement of political forces. Since early March, the number of infections and deaths due to COVID-19 has increased rapidly all over Brazil. The majority of states are experiencing overloaded ICUs. On March 22, in the state of São Paulo with 45 million inhabitants, 30,000 people were hospitalized with COVID-19, and of these 12,000 were in ICU beds. By way of comparison, Germany has some 80 million inhabitants and an ICU capacity of 10,000 beds for COVID-19 patients, i.e., just half the capacity per person than the state of São Paulo has.

While the health crisis rages, Bolsonaro continues to speak out against lockdowns and curfews. He even went to the Supreme Court on March 19 with an injunction to prohibit federal governors and mayors from deciding on lockdowns and curfews. This was rejected by the court through the technicality that it lacked the signature of the federal state attorney – it turned out he declined to provide the signature.

At this point, Lira, Pacheco, and the Centrão decided to collect on the deal Bolsonaro had with them: they demanded a change at the ministry of health. Eduardo Pazuello had become health minister in May 2020 as an interim measure after Nelson Teich quit the job after less than a month. Usually, the health minister is a medical professional in Brazil, but Pazuello was a military man with no medical expertise. In his ten months in office, he remained subservient to Bolsonaro and obstructed any systematic coordination of policies to contain the pandemic. Indeed, the customary regular meetings between state governors and the federal president had not taken place for ten months, which speaks volumes alone.

Pazuello was finally replaced on March 23 by Marcelo Queiroga, a cardiologist who immediately made calls for social distancing and masks, and installed a national crisis committee to contain the pandemic. He spoke out against a national lockdown, but his positions represent a large improvement in comparison to the ones of Pazuello, who kept promoting Chloroquine as a treatment against COVID-19.

Just after the first meeting of the crisis committee, which was headed by Queiroga, Lima and Pacheco made a joint statement, while Bolsonaro made his own statement, railing against social distancing once again. The contrast could not have been greater.

Lula is Back

Another event that hit the political scene in Brazil like a bombshell and increased pressure on Bolsonaro was the decision by the Supreme Court judge Edson Fachin to annul all charges against former president Lula on March 8, which immediately made him eligible for political office. Lula had been sentenced to prison in two separate cases. Fachin had judged, in line with earlier decisions, that the court in Curitiba, headed by the future Minister of Justice Sergio Moro, was not legally entitled to judge the cases, since they were not immediately linked to the state-owned company Petrobras. As a result, a court in Brasilia will now decide on the two cases again, but this court can also decide to drop them.

The decision by Fachin was generally seen as being motivated by two issues. First, Fachin aimed to end investigations underway against Sergio Moro for not having been impartial in his judgements against Lula by annulling the sentences; thus, he aimed to protect Moro by absolving Lula. It was, in fact, part of his decision that the investigations against Moro would have to be stopped by virtue of the fact that the sentences against Lula were annulled, but this did not hold in the end.

Second, the embarrassment of the Supreme Court regarding Bolsonaro became so pronounced that it simply decided to overturn the sentences against Lula. Yet, later in March, the Supreme Court officially decided that Moro is to be held under suspicion of not having been impartial in judging Lula, which means that the new court in Brasilia is not able to use existing evidence from the earlier investigations and will have to gather new evidence for the cases, making it improbable that Lula will be sentenced again before the next presidential elections.

In this vein, the decision to annul the sentences against Lula and move them to a new court were as much a political decision, influenced by the conjuncture, as the earlier sentences against him. While earlier the judges wanted to get rid of the PT, they now want to be rid of Bolsonaro. The judges had decided on the same issues various times already, and the decision regarding Moro’s lack of impartiality emerged because Supreme Court judge Carmen Lucia changed her mind and overturned her earlier decision, alleging new facts that were not known to her before, for example, that Lula’s lawyers had been illegally wiretapped by prosecutors.

Lula gave a thundering speech two days after the annulment, demonstrating his ability to reach a wide audience, reiterating his claim that he was the first Brazilian president to have struck an alliance between labour and capital.

The Military, Vaccinations and 24-Hour Cemeteries

In this environment, Lira, Pacheco, and the Centrão were demanding more changes from Bolsonaro, and this time it was the removal of his Minister of Exterior, Ernesto Araújo, one of the most lunatic right-wing fanatics in the government. Most seriously, he was accused of inhibiting imports of vaccines from reaching Brazil in sufficient quantities, due to his constant attacks against China where the bulk of imports of inputs for vaccines are from.

Yet, Bolsonaro repeatedly displays the ability to turn a weak moment into a strength by going on the offensive, and he tried the same thing this time. Araújo left the post on March 29 under general pressure, and Bolsonaro used the opportunity to change five more ministers. The most significant change he undertook was the dismissal of the Minister of Defence, Fernando Azevedo e Silva, who had protected the Armed Forces against the politicization desired by Bolsonaro. The Military manages a strict protocol within its ranks to contain the spread of the Coronavirus, and this has resulted in a low death rate amongst its members. The High Command of the Army was also unhappy with Pazuello serving as Minister of Health, fearing a negative impact on the reputation of the Armed Forces. The removal of Azevedo e Silva led to the three Armed Forces commanders – of the Army, the Marines and the Air Force – offering to resign their posts jointly, in solidarity with the dismissed minister, an unprecedented occurrence. Bolsonaro subsequently dismissed all three.

These actions demonstrated the unity of the Armed Forces against any ideas of transforming it into a pet Bolsonaro can unleash to intimidate political opponents. While intended as a surprise move with the threat of a coup in the background, Bolsonaro’s action is widely seen as having intensified animosity against him in the High Command of the military.

In this way, Bolsonaro has lost the crucial support of the clientelist parties of the Centrão, the Armed Forces, and the corporate and financial elites. While popular support for his presidency is still stable at 33 per cent according to a poll conducted between March 29-31 by Poderdata, Bolsonaro’s rejection rate has increased to 59 per cent. Poderdata conducted the same poll in early February; at that time 41 per cent rejected the Bolsonaro government, while 22 per cent were neutral or indifferent, and 33 per cent supported it. This demonstrates that there is a hard core of supporters for the president despite all the crises and failures. But this might not be enough for re-election if a strong opponent emerges. Lula has not yet announced if he will run for president in 2022, but his speech after the annulment of the sentences against him was clearly presidential in tone.

In the first days of April, the number of COVID-19 infections reached a plateau of about 80,000 new cases per day, and the number of deaths is still rising, having reached a weekly average of 2700 per day. Alone in March, more than 66,000 people died of COVID-19 in Brazil. Vaccination numbers are finally picking up, with 9 per cent of the population having now received a first dose, and the new health minister promising to vaccinate 1 million people per day during April. Experts warn that a new crisis could emerge when cemeteries become overloaded, which could then cause a series of bacterial outbreaks. In the state of São Paulo, cemeteries are already conducting around-the-clock burials to avoid the possibility of new public health risks emerging. All the while, President Bolsonaro mocks television stations that report on the pandemic as “Cemetery TV.” •