Sunset for Podemos: A Farewell?

The creation of Podemos (We Can) in the Spanish state was an important attempt to build an anti-neoliberal and pluralist mass party to the left of social-liberalism. That experience, which started very well, has finally ended very badly. Perhaps, for this reason, the title of this article could have been “Radiance and decline of Podemos … as an emancipatory political project.”

The purpose of this article is to explain why it was necessary to create it and why it was necessary to abandon it. This has also meant reflecting on the balance sheet that can be made and the lessons that can be drawn from the actions of Izquierda Anticapitalista, now Anticapitalistas.1

Podemos arose because the social democratic and Eurocommunist left were at a dead end after the crisis of 2008. The eruption of the indignados of 15M in 2011 was the catalyst for the emergence of new political expectations in a context characterized by the unstoppable progress of the right-wing Partido Popular (PP) against the Socialist government of José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero. Izquierda Unida (IU) was unable to confront neoliberal policies and the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE – social-democratic party) was one of their executors. Both parties bore the heavy legacy of having contributed to the creation of the political regime of the Transition through the political pact with the forces from the Franco regime embodied in the Spanish Constitution of 1978. Both parties were part of that regime and, in the case of the PSOE, one of its main pillars.

Social Demobilization

On the other hand, there was widespread apathy and social demobilization caused in the first place by the misguided strategy of a social pact at all costs (social concertation) of the majority unions, CC OO and UGT, and the inability of the minorities to build a new hegemony within the workers’ movement, except for the LAB and ELA class-oriented unions in the Basque Country. This enabled the reform of Article 135 of the Employment Code, which made the payment of the public debt the priority in the General State Budgets, and the imposition of two regressive employment reforms: first, that approved by the 2004-11 socialist government of José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero, later worsened by the legislation of the 2011-18 government of the PP, led by Mariano Rajoy, which reduced collective labour bargaining, curtailed the role of unions in workplaces and attacked or annulled important rights of the working class, leading to a large wage devaluation, increased inequality, greater weight of capital income than wage income in gross domestic product (GDP), and increased job insecurity and poverty, especially among youth, practically expelled from the labour market.

As a result of all this, the 15M movement emerged as a protest against the worsening of the social situation and out of revulsion against the political swamp. This opened a window of opportunity for substantially modifying the political map in the Spanish state. Podemos came to fill the void indicated and was presented as the tool to create a new balance of forces in the political sphere that, if consolidated, could have helped to encourage a reinforcement of social organization and mobilization.

In this panorama, it is worth making an exception and pointing out the importance of the mass mobilizations of the Diadas or the days and challenges of 2014 and of 1 and 3 October 2017 in Catalonia, which expressed national aspirations and the demand for the right to decide of an entire people, generating the biggest crack yet in the fabric of the 1978 regime and becoming the main factor of its crisis. Moments in which the political left – including Podemos and its allies in Catalonia – missed a golden opportunity to lead the largest democratic mass popular movement of recent decades in the Spanish state and dispute the political hegemony and leadership of the other actors.

But Podemos quickly aged to decrepitude because it ended up accepting the discursive framework and the limits of the 1978 Constitution, the market economy and the European Union as the only possible horizon. This has meant a failure of the Podemos project and a defeat for the left that promoted it. And yet it was inescapable to try. And expedient.

15M in the Genealogy and Raison d’être of Podemos

The eruption of the movement of indignados on 15 May 2011 in the plazas and streets of Madrid – immediately spreading to all the regions of the Spanish state, including Catalonia, Euskal Herria and Galiza – led to the appearance on the scene of the social mobilization of a new generation that did not identify with the parliamentary parties (“they do not represent us”), was particularly affected by austerity policies (“we are not paying for this crisis”), confronted the financial elites who received state aid to rescue the banks (“this is not a crisis, it is a scam”) and denounced the limits of the political regime (“they call it democracy and it isn’t”).

Therefore, it was a movement with an anti-regime vocation, configured around radical democratic demands that called into question the imperfect bipartisan model embodied by the PSOE and the PP, but also the turnismo in the government of the state, now socialist, now conservative, and the electoral model. But it was also constituted as an anti-austerity movement in the face of predatory economic and social policies contrary to popular sovereignty, especially after the reform of Article 135 of the Constitution and the bailouts of Spanish banks, which represented a public investment currently estimated at 65,000 million euros by the Bank of Spain. For this reason, 15M, although in an elementary way, demanded another economy, another model of society and the need for a new Constitution. That was its great contribution and the proof of its creative energy based on the activity of mass sectors. 15M came to have the sympathy of the majority of the population fed up with the austerity period that began in 2008 and the political sclerosis of the system.

The 15M movement meant a rectification to all the parties and unions in the system and opened the way for a popular mobilization sustained by various sectors (the so-called mareas or tides in education, health, public service workers and so on) relatively outside the bureaucracies and with new forms of organization and coordination. 15M generated forms of disobedient mass struggle of a new type, based on the assembly as the organizing matrix, which very soon overwhelmed the traditional organizations. 15M attracted environmental and feminist activists and youth sectors who were having their first experience.

It should be especially noted that 15M, thanks to its criticism of the 1978 regime, made possible the debate on the need for a democratic rupture and the opening of a constituent process, which, over time, led to Anticapitalistas and other sectors to speak plurally, since a set of constituent processes had to be coordinated that took into account the existence of the national question and not only the general dimension of the Spanish state.

But 15M also showed the limits of a social movement without a political expression and, specifically, an electoral representation. In 2013, the political situation was blocked. Very soon, among the most advanced activist sectors, the debate began about the need for a political tool. Although all of them agreed that no political force that could be created could claim the representation of the 15M movement, there is no doubt that Podemos was the beneficiary of the spirit of the indignados.

The Dilemmas of Anticapitalistas

In the months prior to the launch of Podemos, within Anticapitalistas the debate on what to do was structured around three positions. One was to form a left front or a tactical alliance with IU – this had the disadvantage of the recent history of subordination of this organization to the Socialist Party, both in pre-electoral agreements at the state level and in the experience of co-government in Andalusia and many municipalities, as well as its growing discredit among left-wing youth. Another advocated promoting a front of organizations of the radical left, all of them small except in the Basque Country and partially in Catalonia, scarcely established and with sectarian features, which precisely would have meant for Anticapitalistas to stand outside the broad current of massive radicalization that emerged from 15M.

A third, defended by the leadership, proposed an initiative of a new type, since it considered that the existing left structures at that time were incapable of being useful in taking a leap that would take the social struggle to the political plane. This last option turned out to be the majority. In the heart of Anticapitalistas, and its predecessor Espacio Alternativo, there was always the discussion on the need to support the birth of anti-neoliberal organizations of the masses, democratic and capable of fighting electoral battles in a complementary way to the social struggles promoted by the movements. For this reason, when conceiving Podemos, great importance was given to the idea of a party-movement structured from the base in what we later called circles.

Anticapitalistas was the first group on the left to consider the need and possibility of taking a political leap because the mobilization was already showing signs of exhaustion as a result of the state blockade and the recovery of certain initiatives by the parties of the regime that were beginning to emerge from their confusion and initial paralysis in the face of a protest that was as extended as it was unexpected. Thus, Anticapitalistas considered that it was urgent and possible to channel all the energy that emerged after 15M toward a new battle that would unlock a political panorama that objectively acted as a lock. Effectively, there was a great potency in the social and political sector without representation. In this regard, Anticapitalistas had the good sense and tactical audacity to promote the Podemos initiative, whose scope and nature were of such a magnitude that they were going to put all the forces and capacities of the organization to the test.

What would have happened if Anticapitalistas had not done this? We cannot know because it did not happen. What we do know is that radical left groups that were not linked to Podemos committed suicide through sectarianism. It is possible that Anticapitalistas would have followed the path of political insignificance like a good part of the groups that remained outside. It probably would not have increased its activist forces and would not have enjoyed the wide audience that its public spokespersons have achieved. It would not have extended its organization to all the autonomous communities. It would not have been able to organize the massive political events, both in person and online, that it has carried out during the Covid-19 pandemic. None of its proposals on the national question or on social inequality would have had the media impact that they have had. It could not have set the political agenda among the vanguard, nor would it have become an ideological and political reference for the sectors most aware of activism. It would not have been able to carry out the experience of working from local, regional and European institutions on anti-austerity and democratic themes favouring the popular classes. At this point it should be noted that Pablo Iglesias and his team very quickly obstructed, through the abuse of anti-democratic regulations, the possibility of anti-capitalist representation in the state Parliament, in which there was a limited presence in one sole legislature.

But these and other issues that appear to the Anticapitalistas credit cannot hide two issues: 1) that already mentioned, that the Podemos project failed and that the Anticapitalistas theses were defeated; 2) that important mistakes were made by Anticapitalistas in the process that led to the triumph of the positions of Pablo Iglesias. Therefore, it is appropriate to remember/critically reconstruct the history of Podemos and take stock of the steps taken by Anticapitalistas to have an overall vision and also be able to understand the other big decision: to abandon Podemos and promote Anticapitalistas as a new political subject.

The Podemos Phenomenon in all its Complexity

The first characteristic of Podemos is that it reflected the feeling of indignation that existed after the 2008 crisis and the socially widespread perception that a minority benefited thanks to the fact that a majority lost a lot. And that this social question is closely linked to the democratic question. Pablo Iglesias, on 22 November 2014, at his most radicalized moment, when the polls made Podemos the biggest political force, from a clearly populist left-wing discourse which was nonetheless functional for the positions of the revolutionary left, affirmed that: “The line of fracture now opposes those who, like us, defend democracy… and those who are on the side of the elites, the banks, the market; there are those from below and those from above… an elite and the majority.”

A second singular characteristic of the birth of this political formation is the relevant and determinant role played by a small but active revolutionary Marxist organization, Anticapitalistas, in the creation and first stage of development of Podemos. Both the founding document “Make a move, turn indignation into political change”2 and the electoral programme for the 2014 European Parliament elections reflect, despite the logical transactions of language when various cultures converge, the hegemony of revolutionary Marxist approaches in the meetings and assemblies of activists. Likewise, the contribution of Anticapitalistas in other areas was essential: giving legitimacy to the electoral proposal in front of the social left, facilitating the initial financial resources, making its small organizational structure available to the project and promoting the rank and file affiliative organization, the circles, across almost the entire territory of the Spanish state.

The third characteristic is that Podemos was born as a party that was extremely open to the incorporation of diverse currents of the social and political left, which soon took shape in the incorporation of sectors breaking from IU, incapable of coming out of their internal crisis and offering alternatives to the demands of a new generation of activists, as well as the interest it aroused in social movements, particularly in the sectors of political ecology and feminism. And it captured the attention of the twentysomething generation outside of politics.

There were three sine qua non conditions for the Podemos project to be built and to be useful. That it maintain its discursive radicality; that it establish stable organic ties with the working-class and popular sectors with greater awareness and combativeness; and that it be organized internally in a democratic way to enable deliberation, the participation of supporters in decisions and the creative and fraternal coexistence of the broad ideological plurality and politics present from the first moment at its heart. This plurality encompassed very diverse aspects, with a broader spectrum of differences than that presented by its three main political components grouped around the figure of Pablo Iglesias, Iñigo Errejón and Anticapitalistas, whose best-known public spokespersons were Teresa Rodríguez and Miguel Urbán.

From its origin, Podemos became an internal battlefield between its three souls. The one represented by the anti-capitalist current – broader than the organization that animated it – which proclaimed the importance of programme and organization in the construction of the new party, as well as the need to promote self-organization and social mobilization, an implantation among working people and the combination of these tasks with those of a slow electoral and institutional accumulation that should be put at the service of these objectives through a two-way party-working people relationship.

Faced with this proposal, an alliance was formed between the left-wing populist sector of Iñigo Errejón and the sector of Pablo Iglesias in the first citizens’ assembly of Podemos, known as Vista Alegre I (for the place where it was held). This alliance was reflected in the creation of a bureaucratic clique made up of two factions, constantly remodelling according to the internal balance of forces, whose mission was the absolute control of Podemos. The short-term goal of the alliance was to defeat revolutionary Marxist positions.

The specific objective of Pablo Iglesias was to establish himself as the undisputed leader with total autonomy, without specifying a project outside of electorally overtaking the Socialist Party (PSOE) and coming to government quickly. For this he did not hesitate to radicalize or moderate his discourse at will. He never proposed a project of society, a government programme or a strategy to follow, nor were the conditions and measures to face the attacks of capital considered. Nor were the lessons learned from the Troika’s intervention in the Greek case of Syriza. The old reformist confusion between entering government and having power was repeated, yes, with radical speeches that connected with the challenging spirit of the moment. All his political action has been characterized, with a more or less leftist discourse, by exercising personal hyper-leadership in a simplistic imitation of the less interesting aspects of the Bolivarian experience, but also by what we could qualify as a programmatic relativism that allows proposals to be made and disappeared from a mixed bag according to the tactical convenience of the moment, without any relation to a project of society or strategy to achieve it. The strategic hypothesis was “we were born to govern”; that is, to access government as an end in itself.

In this task, Iglesias initially found a very functional ally in Errejón, a follower at that time of the theses of Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe on the total autonomy of politics and the denial of the role played by social classes and economic conflict in the capitalist mode of production.3 Therefore, from this sector, the speeches and even the articles in the press were filled with abstract disquisitions about the construction of the people subject through the creation of an ideologically transversal interclass electoral base around the mobilization of sentiments for a leader capable of confronting the people with a narrow oligarchic minority. This implied assuming the inappropriateness of left and right categories or of class analyses, and so on. Errejón theorized the possibility of a rapid electoral victory, to which everything had to be subordinated: efficacy versus democracy, hierarchy versus grassroots organization in circles, electoral war machine (a literally formulated expression) versus mass party, plebiscite participation versus democratic deliberation. After the first internal victory of the clique, the circles ceased to have the capacity to make decisions and the election of leaderships was made outside of them, through online voting by people who registered using a form on the website. That was the only commitment of the membership. Elections were without debate and personalized. This was an option absolutely antithetical to that of the activist party and that of the organized mass party. Control and revocation of the leaders by the rank and file was therefore impossible.

These theorizations did not lead to a theoretical and ideological debate of quality either in the academic or political circles, beyond those that could be carried out by a minority very involved in the construction of Podemos, whether they held one position or another, or in the defence of the bipartisan establishment. Although the elections to the Spanish Parliament of 2015 and 2016 were an important result for Podemos, they did not bring the longed-for overtaking of the PS. The electoral decline began along with a search for votes by abandoning any radicalism. The populist moment – Laclavian, broadcast in the Spanish state by Chantal Mouffe in the main national newspaper, El País – was reduced to mere populist mode.4 The ballot boxes reduced theorizations to ashes.

In the following congress, Vista Alegre II, the Iglesias sector turned left and purged the Errejón sector. The clash between these two bureaucratic apparatuses for control of the party expressed what Jaime Pastor and I described as “Pablo Iglesias vs. Iñigo Errejón: between revived Eurocommunism and the neo-populism of the centre.”5 For others, like Emmanuel Rodríguez, the clash was another expression of the ideology and conception of the politics of Podemos as a mere generation of elites, a struggle between them and fulfilment of the aspirations of the university components of a progressive middle class without future.6 The degree of sectarian confrontation between the two factions of the ex-allies through the press and social networks prior to the holding of the second citizens’ assembly threatened its being held. Despite the general inflamed atmosphere, the congress was held thanks to the work and sanity of Anticapitalistas, as one journalist, Raúl Solís, with little affinity to revolutionary Marxism, described in his chronicle, expressing surprise that the revolutionary Marxist left had a “sensible attitude.”7 For a few months, Pablo Iglesias’s left turn favoured the Anticapitalistas policy. But Iglesias attacked pluralism. First, he marginalized Errejón, the true Epimetheus of this story, who, when he discovered belatedly the type of party he had designed and was able to see what was coming out of the Pandora’s box of Podemos, decided to break for political reasons, but above all because he could not breathe in an organization without democracy. Immediately afterwards came the purging, by means of bureaucratic measures, of Anticapitalistas.

Very soon Iglesias began an evolution, with turns to the right and left, toward his youthful conceptions of Eurocommunist roots; he even recuperated the memory of Santiago Carrillo, the leader of the Communist Party of Spain (PCE) who, together with Enrico Berlinguer, of the Italian Communist Party, and Georges Marchais, of the French Communist Party, were the fathers of Eurocommunism, the new form (as they themselves called it) to gain access to government through the parliamentary system. Iglesias began to identify the benefits of the 1978 Constitution as a democratic social shield, as if it could be divided and each article had no connection to another or responded to a logic of legitimation of the post-Franco liberal regime, speaking of its partial reform “when possible.”

Although Pablo Iglesias used Laclau’s conceptual framework in his discourse, he was probably not a devout disciple of it, but he was the beneficiary. The theories of the post-Marxist intellectual went well with the electoralist route to power and with the preeminent role of Iglesias in the process. Abstract appeals to democracy as the tool to transform society within the framework of the institutions of liberal democracy – which are not questioned – lead to the impotence of left-wing populism and Eurocommunism to be able to govern while substantially improving, in a lasting way, the living conditions of people in a situation of economic crisis; even less to transform society. Stathis Kouvelakis is right when he criticizes Laclau because his concept of radical democracy, which excludes rupture with the capitalist socio-economic order and with the principles of liberal democracy, is self-limiting. And remember that, contrary to what Laclau affirms, it is the class struggle that acts as an “agent of reification of the political subject” and not so-called “populist reason.”

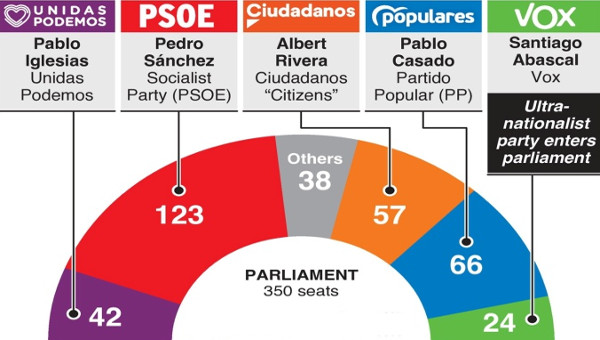

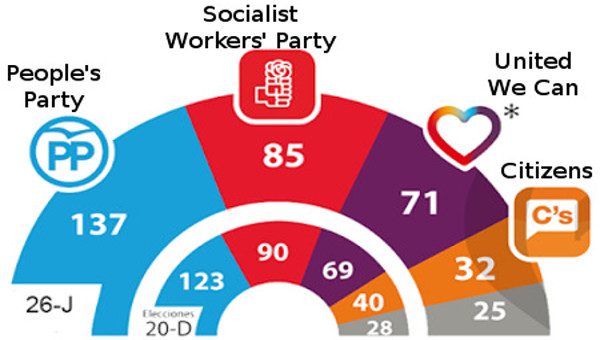

In each of the following elections, including those of 2019, in which Pablo Iglesias headed the Podemos alliance with IU called Unidas Podemos (UP), the loss of votes and seats was constant and overwhelming. Weight and presence in the media were declining; Podemos no longer set the political agenda or the issues of public debate and the prestige of the organization – which was very high initially – declined with each opinion poll. And the desperate search for more traditional left and centre-left spaces began in search of the missing votes. The same result and fate has befallen Más País, the split led by Iñigo Errejón. If initially Podemos had a great capacity to attract with its challenging and winning discourse, the electoral results transformed that impetus into a stark and possibilist “we were born to govern.” This turn was favoured by the process of political involution of IU with the triumph of governmentalist theses and increasing subordination to Podemos.

The Weaknesses and Mistakes of Anticapitalistas

The result of the reformist/revolutionary confrontation within Podemos was not assured in advance, but there were real possibilities. This required leaving the comfort zone in which the small groups and sects of the radical left settle so often, limiting their activity to self-construction, denunciation and summons to other political agents and propagandism without the will or ability to design political projects for and in relation to mass action. Anticapitalistas bet big, had audacity and unleashed its programmatic and tactical potential.

The task was Herculean: to build a mass party from scratch in a situation of social crisis, but with little culture and traditions of organized militancy. In a context of crisis of the political regime – given the disaffection of the youth and the extent of the Catalan conflict with the central state – but with the post-Franco state apparatuses intact, without fissures. With a bipartisan crisis that caused a situation of ungovernability, but with a stabilizing PSOE that retained the confidence, diminished but still in the majority, of the people of the left. Under these conditions, the construction of the alternative was a difficult mission. The factors that explain the existing window of opportunity for the construction of Podemos could play as its Achilles heel; for example, the years of destruction and regression of the consciousness of the workers’ movement and the collapse of the reformist and revolutionary political left; but, above all, that the organic crisis had not yet occurred. All of this objectively hindered the success of the Anticapitalistas project to make Podemos an emancipatory lever.

However, it is necessary to highlight some errors and weaknesses that, apart from the objective difficulties, weighed down Anticapitalistas. A first error was to accept the de facto narrow framework that the clique imposed through the legalization in a secret and manoeuvring way of anti-democratic and hierarchical statutes that granted legal ownership to the Iglesias team. With this, an attempt was made to hide Anticapitalistas as a founding political subject and present their activists as external conspirators, entryists and enemies of the project (sic) that they themselves had created! Let the reader remember the portrait of the Lenin and Trotsky rally whose image was censored and modified by Stalin in a display of photographic magic to erase memory and make the revolution patrimonial. Well, something like this happened in Podemos. How to characterise this attitude of Anticapitalistas? Today there is only one adjective: naive irresponsible trust.

There was a wilful overestimation of the capacity for action of our modest organized militant forces, not so much to back up the initial spontaneous and massive response of the activists, but in the face of the hyper-leadership built in the media and the plebiscitary link existing (and fostered) between the charismatic leader and the masses. This without any process of deep politicization, training of cadres, systematic structuring of the militancy and organic relationship with broad sectors of the people of the left, and yet with a deep feeling of need for change and new directions and new representatives existing. This factor was key in the level of autonomy that Pablo Iglesias achieved in his role as secretary general – elected apart from the rest of the leadership in a plebiscitary manner – to impose his dynamics on Podemos, corner any proposal for democratic structuring and justify every type of political lurch based on his interests at each juncture.

At this moment Podemos set up the so-called “media command” with Santiago Alba which, for a short period of time, effectively revolutionized political communication both on social networks and in its relationship with the audio-visual media. This partisan device was appropriated exclusively by the Iglesias-Errejón tandem. Faced with this, Anticapitalistas – given that access to the Podemos community was vetoed by the bureaucratic clique – did not organize, even in an embryonic way, a communications system, however modest, that would allow it to express its positions in the media and social networks in an autonomous way. This has long been one of the heaviest burdens that has hampered its activity.

Neocaudillismo in the Spanish state was inspired ideologically, politically and organizationally by the Latin American populist experiences today in decline, but the leadership of Podemos defended its “conjunctural” and “instrumental” necessity with the mantra of its convenience and opportunity faced with “electoral and communicational logic in the society of the 21st century.” The next problem, connected to the previous one, is that Anticapitalistas did not detect in time that this caudillismo connected very well with sectors coming from post-Stalinist experiences and in the main depoliticized, who willingly accepted the hierarchy of the organization, in which many of them began to call themselves soldiers.

This rapid bureaucratization process was favoured because some left-wing activists in the social movements, lacking sufficient political awareness, initially mistrusted Podemos and the anti-capitalist sector could not count on their help at a crucial moment. After the electoral success of the new party they approached it blinded like mosquitoes in the light. Too late to modify the organization in a democratic key. Without a political direction, some settled into the new situation, others simply looked for a job in the institutional interstices, and most left Podemos along with a large part of those who had joined.

In this situation, Anticapitalistas made a mistake in Vista Alegre I. Since the framework of dispute was centred on the organizational model, it focused its effort almost exclusively on responding to the internal democratic question, a really important issue, but without putting enough energy into the battle for a political project to have added existing currents of radicalization to the environment of Anticapitalistas. A lesson from then and for the future: establishing the relationship between the political project and the aspiration to an eco-socialist and feminist society is the sine qua non condition for building strategic political groupings that should have a horizon of post-capitalist society. Only in this way can an antagonistic historical bloc be created and unified. Anticapitalistas failed to put this issue at the centre of the construction of Podemos and this allowed the leadership of Podemos to manœuvre and change political positions at will and, therefore, define the objectives based on their immediate interests.

But the fundamental question is that if the task was Herculean, Anticapitalistas was lacking in numbers but also in its social implantation and, even more significantly, in the degree of political cohesion it had before undertaking the project that the party leadership proposed. For this reason there were some losses of a less audacious, more sectarian and leftist sector that after a short time was non-existent. But there were also losses in a sector that reduced its expectations to the electoral route and that no longer saw the need for the existence of the revolutionary Marxist organization in the framework of a broader one.

The Anticapitalistas leadership had a good reading of the situation that led to the conclusion of founding Podemos, but not of the political requirements to tackle that leap. A lesson can be drawn from this question, and thinking about the post-Podemos tasks: the need to have significant ideological and strategic preparation in the party prior to making decisions of this magnitude. But since the situations in which new windows of opportunity that allow qualitative leaps will be presented cannot be magically guessed or scientifically predicted, it is imperative to create in a conscious and planned way an internal consistency in the party superior to that which spontaneously and routinely occurs. This must be a constant central task that will be of great use to act in unison, with strategic thinking, tactical ingenuity and organizational creativity, so that opportunities and possibilities are transformed into strengths and realities.

We Will See Each Other in the Struggles

As Raúl Camargo explained in an interview, the underlying reasons for the departure of Anticapitalistas from Podemos are twofold.8 On the one hand, the absence of internal democratic life in an organization whose bodies rarely meet or deliberate, where proportionality is not respected for the election of positions of internal leadership or in the electoral candidacies decided by the general secretary, all of which prevents the development of a pluralistic organic life. On the other hand, because the process of acceptance of the constitutional framework of the 1978 regime and flexible adaptation to the market economy by the Iglesias team has been accompanied by an approach to the PSOE, which has culminated in the formation of a joint government in which UP plays a subordinate and secondary role.

UP’s budget agreements with the PSOE and the coalition government programme have been subordinated to the requirements of the Stability and Growth Pact. It is a government that, under the hegemony and attentive vigilance of economy minister Nadia Calviño, has an economic and social policy determined by the limits set at all times by the European Commission, the Council, the Eurogroup or the ECB. The social soul that inspires Podemos is undeniable, but its proposals, and this has been shown in the pandemic, have a limited scope. The measures in defence of the most disadvantaged are necessary as a palliative but insufficient, those on the employment front have an expiry date and rest on an even greater indebtedness of the state coffers and relief for business profits.

In the short experience of the so-called government of progress, UP has made a cataract of concessions, even renouncing aspects of the programme agreed with the PSOE and has silently consented to important political setbacks and economic decisions. One of the next tests will be its attitude to the flagrant crisis of the monarchical institution, which will not be defeated only with pronouncements in parliament.

It is of little use to regroup the people, appeal to the interests of the people, have an electoral presence or be part of a government if it is not around a project that ends their alienation. Which, even more so, forces us to remember categories such as social class and exploitation; to conceive the social majority not as an arithmetic sum of individuals but as an algebraic aggregate of the working class with all social sectors with outstanding accounts with the system and capable of configuring a new hegemonic block. In other words, conceiving the people as a real antagonistic political subject and candidate for power in every way. This is quite different from limiting their advances to mere occupation by a new elite of professionalized young politicians of a few marginal ministerial portfolios.

Podemos has become a plebiscitary electoral apparatus that, while it represents a part of the left, although in a diminishing way, is an impediment to the development of popular self-organization. On the one hand, because under its leadership the political struggle has been reduced to a merely institutional one; on the other, because it has an instrumental relationship with social organizations. This is complementary and functional with the government orientation of Iglesias, characterized by governing at all costs, to insert itself into the progressive management structure of the state apparatus, limiting the work agenda to possibilist criteria and renouncing the objective of transforming the political, economic and social system; constantly assuming the logic of the lesser evil, as can currently be seen in the management of the post-Covid-19 social crisis.

In summary, the current X-ray of Podemos is that of a hierarchical party whose leadership bodies have no life, identified with the parliamentary group and with the members of the government, a party that has almost completely lost its activist base and has reduced its political action to an institutional presence lacking ideas and transformative proposals. And its main object of reflection is its location in the state structure and in the vicissitudes of Podemos itself. A party that, in the classification made by Antonio Gramsci in his “Brief Notes of Machiavelli’s Politics,” is dedicated to “small politics,” to “partial and daily questions that arise within an already established structure in the struggles for pre-eminence among various factions of the same political class.” And which has abandoned “grand politics,” which really “deals with questions of the state and social transformations.” And has made the mistake – of which Gramsci already warned – of not understanding that “every element of small politics” becomes “a matter of grand politics.”

This is not good news. The current political situation does not favour leftist positions, it presents great difficulties and challenges in the absence of the mediation of a mass party. But this observation cannot ignore the positive aspects indicated above for Anticapitalistas having undergone this experience and this makes it possible for the revolutionary Marxist organization to continue playing, as Brais Fernández suggests, an active role in the crisis of the 1978 regime.9 To do this, it must promote new political and social alliances in the face of austerity policies, continue working for the creation of new anti-neoliberal groups with mass influence, as is the case with Adelante Andalucía, promote the organization of trade union, social, environmentalist, feminist, youth and social struggles and those in defence of the public sector, and to be an ideological and cultural reference point in the ongoing debates to define a new ecofeminist and social project. •

This article first published on the Europe Solidaire Sans Frontières website.

Endnotes

- Izquierda Anticapitalista participated in the process of creation of Podemos in 2013 and 2014 before renaming itself as Anticapitalistas. Since there is an absolute political and organizational continuity I use the name of Anticapitalistas throughout the entire article for my convenience and to facilitate the reading of those who access the text.

- See available on ESSF, “Spanish State: Podemos Manifesto – Turning outrage into political change.”

- Suddenly, for a short period of time, the shop windows of the bookshops were filled with works by Laclau such as On Populist Reason, Hegemony and Socialist Strategy by Laclau and Mouffe or Podemos: In the Name of the People by Mouffe and Errejón. What I don’t know is whether they had real success with readers.

- See El País 10 June 2016 “El momento populista.”

- ESSF, “Spanish state: a revived Eurocommunism vs centrist populism.” For an additional assessment of Vista Alegre II (2017) see Raul Camargo, ESSF, “Podemos (Spanish State): Vista Alegre II Assembly – The show is over, are the politics starting?”

- See Viento Sur 7 February 2017 Emmanuel Rodriguez “El podemismo como problema y como ideología.”

- See Huffington Post 8 February 2017 “La cordura de los anticapitalistas de Podemos.”

- See ESSF, “Spanish State: Anticapitalistas leave Podemos.” Original El Diario, 17 May 2020 “Raúl Camargo: ‘El Podemos del Gobierno con el PSOE no es el original, ha evolucionado hacia posiciones más moderadas’.”

- See Viento Sur 14 April 2020 “Y después de Covid19, ¿qué hacemos? Notas para una discusión en la izquierda.”