Following Mexico’s Worker Strikes, the US Steps in to Keep Border Factories Open

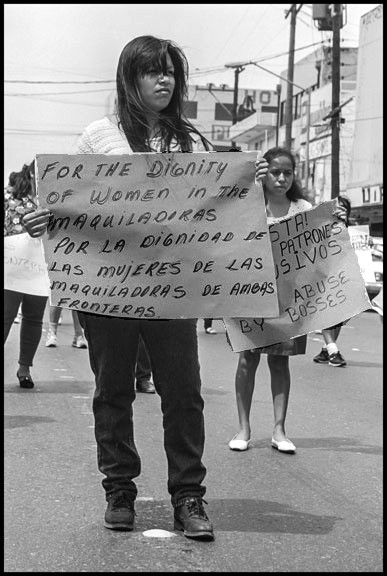

In Washington, D.C., President Donald Trump is trying his best to reopen closed meatpacking plants, as packinghouse workers catch the COVID-19 virus and die. In Tijuana, Mexico, where workers are dying in mostly US-owned factories (known as maquiladoras) that produce and export goods to the US, the Baja California state governor, a former California Republican Party stalwart, is doing the same thing.

Jaime Bonilla Valdez rode into the governorship in 2018 on the coattails of Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador. And at first, as a leading member of López Obrador’s MORENA Party, he was a strong voice calling for the factories on the border to suspend production.

López Obrador himself was criticized for not acting rapidly enough against the pandemic. But in late March, in the face of Mexico’s rising COVID-19 death toll, he finally declared a State of Health Emergency. Nonessential businesses were ordered to shut their doors, and to continue paying workers’ wages until April 30.

Bonilla’s Labor Secretary Sergio Martinez applied the federal government’s rule to the foreign-owned factories on the border, producing goods for the US market. Again, only essential businesses would be excepted.

When news spread that many factories were defying the order to close, Bonilla condemned them. “The employers don’t want to stop earning money,” he said at a news conference in mid-April. “They are basically looking to sacrifice their employees.” But now, a month later, he is allowing many non-essential factories to reopen.

Explaining the about-face are two competing pressures. At first, workers in the factories took action to shut them down, a move widely supported in border cities. But as the owners themselves resisted, they got the help of the US government. The Trump administration put enormous pressure on the Mexican government and economy, vulnerable because of its dependence on the US market. Now as the factories are opening again, the deaths are still rising.

Strikes Start in Mexicali

Although Baja California is much less densely populated than other Mexican states, it’s now third in the number of COVID-19 cases, with 1,660 people infected. Some 261 have died statewide, and 164 in Tijuana alone. That’s more deaths than 131 in neighboring San Diego, a much larger metropolis. Fifteen per cent of those with COVID-19 in Tijuana die, while only 3.5 per cent die in San Diego. As is true everywhere, with the absence of extensive testing, no one really knows how many are sick.

In Tijuana, most who die are working-age. Since one-tenth of the city’s 2.1 million residents work in over 900 maquiladoras, and even more are dependent on those factory jobs, the spread of the virus among maquiladora workers is very threatening.

Alarm grew when two workers died in early April at Plantronics, where 3,300 employees make phone headsets. Schneider Electric closed when one worker died and 11 more got sick. Skyworks, a manufacturer of parts for communications equipment with 5,500 workers, admitted that some had been infected.

In the growing climate of fear, workers began to stop work. In Mexicali, Baja California’s state capital, workers struck on April 9 at three US-owned factories: Eaton, Spectrum and LG. Protesters said the companies were forcing people to come to work under threat of being permanently fired, refusing to pay the government-mandated wages and failing to provide masks to workers. The factories were forced to close by the state government.

Work then stopped at three more factories – Jonathan, SL and MTS. There, the companies offered bonuses of 20-40 per cent if workers would stay on the job, but employees rejected the offer. One striker, Daniel, told a reporter for the Mexican newspaper La Jornada, “We want health – we don’t want money, or bonuses or even double pay. We just want them to comply with the presidential order that nonessential factories close, and to pay us our full salary.” Jonathan makes metal rails for machine guns and tanks for US companies. Workers denied company claims that they made “essential” telecommunications equipment, a common claim by factories that want to stay open.

The Organization of the Workers and Peoples, a radical group among maquiladora workers in Baja California, reported a week of work stoppages at Skyworks, and a strike at Gulfstream on April 10. At Honeywell Aerospace, workers began shutting down production on April 6. “The company then laid off 100 people without pay, and fired four of them,” said Mexicali worker/activist Jesus Casillas. Honeywell closed for a week, and then reopened.

As the strikes progressed, workers reported the death of two people in Clover Wireless’s two plants that repair cellphones. They were closed for one shift, and then started up again. Finally, on April 14, a general strike was called by Mexicali maquiladora workers, and supported by the state chapter of the New Labor Center, a union federation organized by the Mexican Electrical Workers Union.

The Factories Don’t Actually Close

Companies that said they were closing never really did, workers charged. “They’d close the front door and put a chain on,” Casillas explained. “Then they bring workers in through the back door. They’d call the workers down to the factory, and would tell them that if they didn’t go back to work, they’d lose their jobs permanently.”

Elsewhere on the border, workers also complain about being forced to work. Company scofflaws even included breweries. In the rest of Mexico, beer began to disappear from store shelves as a result of López Obrador’s order, shuttering breweries because alcohol production was not deemed “essential.” Modelo and Heineken, two huge producers, complied. Constellation Brands’ two enormous breweries in Coahuila, which make Corona and Modelo for the US market, did not.

On May Day, a Facebook post even showed workers lined up without masks at the Piedras Negras glass plant that makes the bottles for Constellation Brands. A message from a worker, Alejandro Lopez, charges, “We ask for masks and they deny us, like they do with [sanitizing] gel, which they only give us at the [brewery] entrance, and that’s it.” The response posted by the plant human-relations director, Sofia Bucio, says the company does everything required, and then goes on to berate the worker: “We didn’t go take you out of your house and force you to work with us, right? If you don’t like the measures IVC [the glass company] is taking, the doors were wide open to let you in when you came here, and they’re the same to let you out.”

In border cities across the Rio Grande from Texas, other factories that wanted to stay open said they’d let workers worried about the virus stay home, but only at 50 per cent of their normal wages. “People can’t possibly live on that,” charged Julia Quiñones, director of the Border Women Workers Committee. Since López Obrador ordered a raise a year ago, the minimum wage on the border has been 185.56 pesos ($7.63) per day. Fifty per cent of that, in Nuevo Laredo, would barely buy a gallon of milk (80 pesos).

“There’s no other work the women can do in town,” Quiñones explained. “In the past, some workers crossed the border to earn extra money by donating blood. But the border is now closed, even for those that have visas. They can’t sell things in the street because of the lockdown. The only option is to work.”

One worker told her, “It is better to work at 100 per cent, even if we’re risking our lives, than to be at home with 50 per cent.”

Meanwhile, work stoppages spread to other border cities, as the death toll rose. Lear Corporation, which employs 24,000 people making car seats in Ciudad Juárez, closed its 12 plants there on April 1. Lear had more COVID-19 fatalities than any company on the border. It won’t cite a number, and says it only learned of the first death on April 3. By the end of April, however, 16 Lear workers were dead from the virus, 13 from its Rio Bravo factory alone.

As other plants continued operations despite a death toll, strikes broke out. On April 17, workers struck at six maquiladoras, demanding that the companies stop operations and pay workers the government-mandated wages. Twenty people in the city had died by then, including two workers at Regal Beloit (a coffin manufacturer), and two workers at Syncreon, according to protesters. At Honeywell, 70 strikers said the company hadn’t provided masks, and had forced people with hypertension and diabetes to show up for work.

The Electrolux plant stopped work on April 24 after two workers, Gregoria González and Sandra Perea, died. Two weeks earlier, workers there had protested the lack of health protection. When workers finally stopped working, the company locked them inside and later fired 20. One told journalist Kau Sirenio, “The company wouldn’t tell us anything, though we all knew that we were working at the risk of getting infected. They waited until two died before they closed, and fired those who protested the lack of safe conditions. They still say their operation is essential, but you can see how little they care about the lives of the workers.”

In Juárez, the mayor closed the city’s restaurants but allowed the maquiladoras to keep running. When workers at TPI Composites began their protest, the city police were even called out against them. Nevertheless, in Juárez and other border cities throughout April, the pressure of workers did succeed often in forcing the government to demand compliance from the companies.

The US Intervenes

At the end of April, the US government intervened on behalf of the owners of the stalled plants. The Trump administration is set on protecting the new United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement set to go into effect on July 1. While the agreement has theoretical protections for worker health and safety, there is no expectation that it would be invoked to ensure that plants remain shut until the COVID-19 danger recedes. Instead, its purpose is to protect the chains of supply and investment between Mexico and the US, especially involving factories on the border.

López Obrador’s order classified as “essential” only companies directly involved in critical industries such as health care, food production or energy, and excluded companies that supply materials to factories in those industries. But from the beginning, many maquiladoras claimed they were “essential” anyway because they supplied other factories in the US. Luis Hernandez, an executive at a Tijuana exporter association, admitted, “Companies have wanted to use the ‘essential’ classifications of the US.”

The military-industrial complex has a growing stake in border factories, which exported $1.3-billion in aerospace and armament products to the US in 2004, climbing to $9.6-billion last year. To defend that huge stake, Luis Lizcano, general director of the Mexican Federation of Aerospace Industries, told the Mexican government it had to give Mexico’s defense industry the “essential” status it enjoys in the US and Canada.

Pentagon Undersecretary of Defense for Acquisition and Sustainment Ellen Lord announced she was meeting Mexican Foreign Minister Marcelo Ebrard to urge him to let US defense corporations restart production in their maquiladoras. “Mexico right now is somewhat problematical for us, but we’re working through our embassy,” she said. She later announced her visit had been successful.

Using the language of the Trump administration, US Ambassador Christopher Landau played down the risk to workers. “There is risk everywhere, but we don’t all stay at home out of fear that we’re going to crash our cars,” he said in a tweet. “Economic destruction also threatens health… On both sides of the border, investment = employment = prosperity.”

Finally, on April 28, Baja Governor Bonilla bowed to the pressure and ordered the reopening of 40 “closed” maquiladoras. According to Secretary of Economic Development Mario Escobedo Carignan, they are now considered part of the supply chain for essential products. “We’re not in the business of trying to suspend your operations,” he told owners, “but to work with you to keep creating jobs and generating wealth in this state.”

Given that many “closed” factories, in fact, were operating already, Julia Quiñones said bitterly, “This is what always happens here on the border. The companies break the law, and then the law is changed to make it all legal.” And Mexico’s federal government itself has begun to back down as well, announcing three days after a US request that it will allow the many enormous auto plants in Mexico to restart their assembly lines once automakers restart them north of the border.

The announcements didn’t indicate that Mexico had flattened the coronavirus infection curve or that the factories were now safe. In one 24-hour period, from April 29 to 30, the number of cases per million people went from 138 to 149. A million workers labor in over 3,000 factories on the border. The virus has already led to numerous deaths among them, and if all factories resume production while it still rages, the death toll will surely rise.

Luis Hernández Navarro, editor at Mexico’s left-wing daily, La Jornada (no relation to the Tijuana businessman), reminded his readers that the catastrophic spread of the virus in Italy was caused by the continued operation of factories in Lombardy until it was too late.

“The maquiladora industry has never cared about the health of its operators, just its profits,” he wrote recently. “Their production lines must not stop, and in the best colonial tradition, Uncle Sam has pressured Mexico to keep the assemblers operating… The obstinacy of the maquiladoras makes it likely that the Italian case will be repeated here.” •

This article first published on the Truthout website.