The Myth of State Neutrality

Police Violence, Labour, and the Unifor/Co-op Struggle

We are taught at a very early age and socialized throughout our lives to respect and obey the rule of law. British Columbia Premier John Horgan recently invoked, rather infamously, the rule of law in justifying RCMP assaults on Wet’suwet’en defending their territory against imposition of the Coastal GasLink natural gas pipeline (never mind that his rule of law erases recognition of Wet’suwet’en law on unceded Indigenous territory). Saskatchewan Premier Doug Moe too has invoked rule of law in suggesting that locked out workers, Unifor members in Regina, take down picket barriers at the Federated Co-op Ltd. Refinery (even as police assist scabs getting into and out of the workplace).

These appeals, and associated language such as “enforcing injunctions” seek to remove politics from crucial issues of social and environmental justice and Indigenous sovereignty. They attempt to render issues of great ethical significance as simply legal or technical applications.

The notion of rule of law rests on an even deeper foundation – the notion of neutrality of the state. We are told that the state is an impartial, disinterested, neutral arbitrator. It takes no sides, only views and assesses evidence impartially and detached from specific interests. Serving only the rule of law, and thus, why it is granted these special powers.

In times of open labour conflict, strikes and lockouts, picket actions by workers at workplaces – as in Indigenous land struggles – we see perhaps most clearly, as everyday appearances are torn away, that the state is not neutral – it is an interested actor. And we can come to see that throughout Canadian history the state has taken sides, and it continues to do so.

The Role of the State

The history of labour movements is a history of one-sided, interested, state action – for capital against workers. In terms of labour conflicts, we can see the state taking sides at multiple levels. In injunctions that limit worker, union, and supporter actions in defense of jobs and working conditions (and pensions). To the benefit of employers. We can see it too in back to work legislation, as imposed in recent years against the Canadian Union of Postal Workers and Air Canada workers. And perhaps most forcefully we see it in the deployment of police against striking or locked out workers as in the case of Unifor members in Regina.

Note that police are not deployed to force employers to close operations during a strike or lockout. They are not deployed to prohibit the transport of scabs into a struck or locked out workplace. This despite the fact that the use of scab labour is an intense provocation. Indeed, one of the most aggressive escalations employers can use against striking or locked out workers.

During an interview I did recently with Canadian Broadcasting Company reporters in Regina, very thoughtful and open minded as they were, the journalists were struck by the nature of police actions. They asked variations of a similar question: “Is the province asserting force,” “Is the government taking sides,” “Is police involvement proper?” It was if they could not believe what they were seeing. When I mentioned that state neutrality is a myth, they seemed legitimately shocked.

In what follows I want to touch on some aspects of “neutral” state action, particularly policing in this context.

Policing Class Struggle in Regina

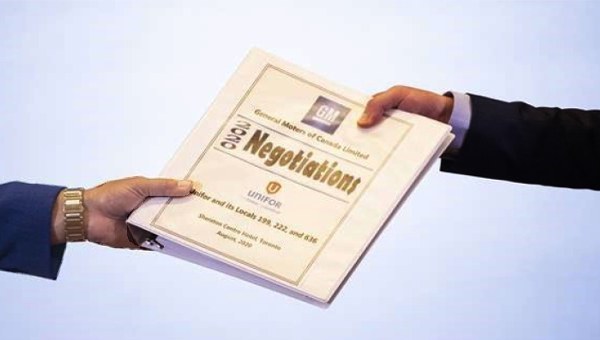

More than 700 workers at the Federated Co-operatives Ltd. Refinery in Regina have been locked out of their jobs since December 5 in a struggle largely focused on company attacks on worker pensions. Regina Police Services have publicly insisted, as police typically do, that they are neutral in the conflict, not taking sides (that myth of state neutrality again). Yet their actions in crucial ways show otherwise.

Barricades at the refinery were put up by workers on January 20, as the conflict deepened. Unifor national president, Jerry Dias, and western regional director, Gavin McGarrigle, were arrested by Regina police. This intensification occurred as the company relied on police to weaken the pickets and make it easier to move scabs into the refinery to continue operations and get trucks in and out.

On February 5, four Unifor Local 594 members were arrested at Gate 1 at the refinery. On February 6, Scott Doherty, the executive assistant to Jerry Dias was arrested by Regina police and charged with mischief and disobeying an order of the court. He was released with imposed conditions that prohibit him from being within 500 metres of the refinery.

The following morning, February 7, Regina police moved to stop picketers from approaching the refinery. They also had refinery security remove fences set up as barriers by the union. The real purpose in all of this was to assist the company in getting trucks into the Co-op Refinery. Regina Police Service justified their actions by saying they were removing the barricades to make the area safe, in accordance with a December court order. These acts, far from making the area more safe, serve as an act of aggression against union workers on behalf of the company.

The company has pursued a contempt of court decision against picketing workers. An earlier court decision restricted Unifor Local 594 members to only blocking fuel trucks at the refinery for a maximum of 10 minutes. The union has already been fined $100,000 for breaching that order.

At a court hearing on February 6, Federated Co-op Ltd. called for two union members to receive jail time. They have also asked for the court to issue a $1-million fine against the union. A Court of Queen’s Bench judge reserved his decision at that hearing.

That same day, in Alberta, Justice Glenda Campbell, did rule that barricades put up at a Federated Co-op Ltd. fuel terminal in Carseland, Alberta, must come down. That injunction though did not include any police enforcement clause. So RCMP were not authorized to force removal of the barricades, though they always have operational discretion to do so.

Regina police had told the union that there would be no action until the court decision was released, but the police moved to facilitate movement of trucks into the refinery the following day put the lie to that promise.

In response to the police escorting of Co-op trucks into the refinery while prohibiting picketers, Unifor released a statement saying in part:

“First Federated Co-operatives Limited (FCL) locks workers out in the dead of winter, then the Regina Police take away their right to picket, but also make sure to cruelly take away the picketers’ limited access to warming shelters and washroom facilities. No judge ruled to freeze out the picketers and refuse to allow them to go to the bathroom. The Regina Police Service has taken the law into their own hands.”

Of course, this is typical of policing, not an aberration. Police always have leeway to exercise discretion. We see this in practices like street checks, which predominantly target racialized people, as well as in the policing of picket lines.

Police actions clearly show that the Regina Police Services openly choosing sides, despite their claims to the contrary. As police always do.

Killing in the Name of…

The true nature of the state as an interested actor in the service of capital is not only a matter of one-sided deployment against picket lines, escorting scabs, or in the facilitation of company production during strikes or lockouts. Throughout Canadian state history, it has proven to be a matter of life and death for working class people.

There is a mistaken belief that in Canada police are generally less brutal or aggressive and labour histories have been free from lethal state violence. Yet a glance at labour history shows extremes of police brutality and violence, including (though seemingly apart from Canadian history) lethal acts against working class people, union organizers, and allies. While it is largely overlooked, forgotten, or never known in the first place, more than a dozen people have been killed by Canadian police in attacks on working class organizing.

A central part of the police function, the key police function, in a colonial class context like Canada, is quelling resistance to economic and political systems of power. While police killings of organizers and activists have been documented and even memorialized within US culture, there has been little public awareness or discussion of the numbers of organizers and activists killed by police in Canada and the range of social issues for which police have killed, in the service of capital. Most instances of police killings of working class organizers and resisters remain too little a part of public consciousness. These include:

- Socialist war resister and miner organizer Albert ‘Ginger’ Goodwin, shot and killed in 1918 on Vancouver Island. The mining companies that dominated over communities on Vancouver Island had long wanted Goodwin removed because of his well established effectiveness as an organizer.

- Striking workers Mike Sokowolski and Mike Schezerbanowicz, shot and killed in Winnipeg during the General Strike in 1919.

- Striking miner William Davis, shot and killed in Nova Scotia in 1925.

- Striking mine workers Nick Nargan, Julian Gryshko, and Peter Markunas shot and killed by RCMP in Estevan, Saskatchewan in 1931.

- Unemployed worker Nick Schaack, shot and killed in Regina in 1935 during the On to Ottawa trek.

- Striking lumber and sawmill workers Irenee Fortier, Joseph Fortier, and Fernand Drouin at Reesor Siding, Ontario.

- Feminist and socialist Michele Gauthier, gassed to death in the streets of Montreal in 1971 while taking part in a march in solidarity with locked out La Presse workers.

We should also note the numbers of Indigenous resisters killed by police in Canada, defending their own lands and cultures. Jake Ice, killed in 1899 for defending Indigenous traditional governance at Akwesasne in 1899. Dudley George, shot and killed defending his community’s land in Ipperwash, Ontario in 1995. In 2015 in British Columbia an Indigenous man, James McIntyre was shot and killed by RCMP for publicly opposing the Site C dam at a consultation event in Dawson Creek. With barely a ripple of outrage among the so-called Canadian public, or even among activist circles.

These killings by police tell essential parts of the history of resistance and repression in Canada. The people killed were struck down by police while seeking a better world than the one of exploitation and oppression. It is telling, too, given Canada’s status as a resource state, the number of people killed while organizing against extractives companies, especially mining. In each case the police took sides – in the case of labour activists killed by police, on behalf of companies, for employers. And that is, fundamentally, a function of police in a class society. Not neutrality.

In contrast to this I would ask for the names of any company owner or director killed by police in order to secure the needs of striking or locked out workers.

The answer to the questions raised in relation to the Unifor/Co-op struggle – “Is the province asserting force,” “Is the government taking sides,” “Is police involvement proper?” – is, in each case yes. In Regina, the “neutral” state is doing the bidding of an oil company. As Unifor is left to conclude, with disappointment, in their statement, the rule of law is indeed in the hands of state actors. And they have never been neutral when it comes to taking sides in conflicts between capital and workers.

As solidarity grows so too will injunctions and police actions, as we have seen in Regina and Calgary and as we are seeing in the assault on Wet’suwet’en people and lands and their allies, and as we often see during picket actions. These will be posed as technical applications of the rule of law, not issues of ethics or social justice. The government will claim it is not taking sides. As its actions meet the very needs the corporations are pursuing. And we will be challenged not to limit our actions within the limits sought by one-sided “neutrality.” •