A Nightmare of Homelessness: A Knapsack Full of Dreams

Cathy Crowe’s book A Knapsack Full of Dreams: Memoirs of a Street Nurse comes out of decades of witnessing and challenging a growing blight of destitution and poverty in Toronto that has developed with the advance of the neoliberal agenda. In writing this review, I should make clear that I have known Cathy for a good part of that time, and in my years as an organizer with the Ontario Coalition Against Poverty (OCAP) have dealt with her as an ally, tackling the same issues and confronting the same injustices. We have worked in different organizations and sometimes taken significantly different approaches, but a sense of common purpose has always existed. Doubtless, my appraisal of her book will reflect this.

Cathy’s role and focus are very much reflected in the term by which she describes herself, that of Street Nurse. As she mentions, this label stuck after “a homeless man across the street yelled out in a jovial manner, ‘Hey, Street Nurse’” (p.125). He was respectfully incorporating her into the ‘street family’ he was part of, but there are other elements to Cathy’s role that go beyond this. Her mother was a nurse who, in her time, came up against the “patriarchal origins of the organizational control of nurses” (p.55). Cathy found herself dealing with this same system of control, linked as it is to an effort to prevent nurses from speaking out against the social injustices they deal with in their work. At the heart of Cathy’s career has been a commitment to “a new nursing movement in Canada composed of politicized nurses” (p.55). I have no doubt that she would agree that this effort is, as yet, a work in progress and that nurses and other health providers who confront injustice still swim against the stream. When he was Mayor of Toronto, the late Rob Ford put things very clearly with his blunt assertion that “[d]octors should not be advocates for the poor.”

Cathy’s role and focus are very much reflected in the term by which she describes herself, that of Street Nurse. As she mentions, this label stuck after “a homeless man across the street yelled out in a jovial manner, ‘Hey, Street Nurse’” (p.125). He was respectfully incorporating her into the ‘street family’ he was part of, but there are other elements to Cathy’s role that go beyond this. Her mother was a nurse who, in her time, came up against the “patriarchal origins of the organizational control of nurses” (p.55). Cathy found herself dealing with this same system of control, linked as it is to an effort to prevent nurses from speaking out against the social injustices they deal with in their work. At the heart of Cathy’s career has been a commitment to “a new nursing movement in Canada composed of politicized nurses” (p.55). I have no doubt that she would agree that this effort is, as yet, a work in progress and that nurses and other health providers who confront injustice still swim against the stream. When he was Mayor of Toronto, the late Rob Ford put things very clearly with his blunt assertion that “[d]octors should not be advocates for the poor.”

Homelessness and other glaring injustices in this society are ever present considerations in the book. However, it is not by any means an attempt to present a complete history of the development of the homeless crisis or the struggles that have been taken up in the face of it. Nor, for that matter, is it a comprehensive autobiography. Cathy’s memoirs tackle themes, draw from events and identify many of the people, historical moments and works of art, especially films, that have inspired and shaped her. The very title of the book is taken from a National Film Board film on the life of one of Canadian social democracy’s leading figures, Tommy Douglas, in which it is suggested that he was “a travelling salesman of sorts with a suitcase full of dreams” (p.23).

What comes through in Cathy’s book, with great force and considerable clarity, is her deep compassion for people facing an incredible and needless assault on their health and emotional well being in the form of homelessness. There is no hyperbole in her reference to “third-world conditions in our cities” (p.157) because the formulation comes from years of experience on the front lines dealing with the worst this neoliberal city has to offer. While her outrage is largely focused on the impacts of homelessness, a wide range of societal injustices lead her to seek a means to challenge them. “I think it’s no accident that my awakenings around peace, disarmament and feminism occurred simultaneously,” she concludes (p.81).

The Political Nurse

Cathy draws a sharp and important distinction between those who provide health services to deal with the “downstream” effects of social injustice and those who venture “upstream” to deal with the causes (p.87). She has been inspired to choose the latter course, based not just on her own life experiences, but through the record left by others. She makes special note of the closing lines of the film on the life of the great Canadian revolutionary doctor Norman Bethune: “The world we fight for will have peace and justice, it will be free of hunger and tyranny, of hatred and privilege and of arrogant use of power.” She is motivated by the pioneer nursing work and social reform efforts of Florence Nightingale, even presenting an imagined conversation in which Nightingale comments on the assault on the health of homeless people that is tolerated in 21st-century Toronto (p.60).

A little further on, we find Cathy, in 1984, putting a resolution before the Registered Nurses Association of Ontario (RNAO) to endorse nuclear disarmament (p.76). This was adopted by their convention, but, no doubt, there were many nurses at the time who didn’t understand as readily as she did just why their representative body should adopt such a position. To her, however, disarmament was simply and clearly the ultimate public health measure, and therefore, nurses should be in the front ranks of the struggle to achieve it.

Cathy continued her development as a political nurse even as she was involved in the most hands-on forms of healthcare provision, as a clinic nurse at Toronto’s South Riverdale Community Health Centre and at several other agencies (p.122). The personal situations (p.129) of those she dealt with as a nurse only reinforced and further developed her understanding of and outrage at the political choices that allow such poverty to exist in a wealthy society.

Like all health and other service providers dealing with people in poor communities, the arrival of the Mike Harris Tory government in 1995 was a terrible moment for Cathy. The need for a political form of nursing was more acute than ever. In an open letter to the Premier in 1997, she set out the impacts of his agenda in the clearest terms (p.137). During these years, homelessness became an ever-more deadly experience, with struggles taken up to expose the situation (p.140). A major inquest into homeless deaths occurred, and every effort was made to ensure it would create momentum for change. Cathy was heavily involved in all this work. At this time, a Tent City of homeless people was established that survived for some three years. Cathy and the Toronto Disaster Relief Committee (TDRC) that she was part of worked to ensure its survival, and when it was finally closed by the authorities, to successfully press the demand that its residents be housed (p.152).

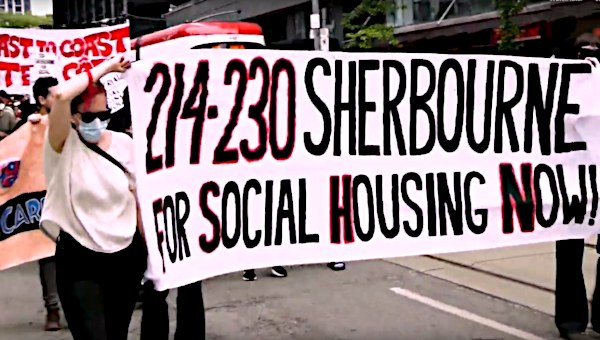

Undoubtedly, Cathy takes the most pride in the TDRC’s successful campaign to have the City of Toronto declare homelessness a national disaster (p.160). The closing words of the book deal with the passage of this resolution by the City Council. She says, “This was the day that the crime of homelessness in Canada was named a disaster and the truth was told. I still hold onto my dream that it can be solved” (p.341). The victory in Toronto led to a broader effort to campaign for housing across Canada (p.247). However, with governments embracing neoliberal austerity and facilitating a profit-driven process of upscale urban redevelopment, the effort was clearly a hard exercise in swimming against the stream. In the chapter on the so-called ‘Housing First’ approach, Cathy takes a principled and clear-minded position of opposition to the prevailing effort to close shelters and displace the homeless from the central areas of cities with a false promise of viable housing for them on the urban fringes (p.285).

The Role of Accuser

There are not a few politicians over the years who will have regarded Cathy Crowe in much the same way as Macbeth viewed Banquo’s ghost. She has played the role of relentless accuser, and there is no doubt that this has produced some very real results. People are alive who would be dead but for her work, and people are housed who would be on the streets. Social crimes against the poor that would have been buried have been dragged into full view. It’s true that the agenda that has fed the homeless crisis has not been turned back or even brought to a standstill, but the speed and intensity of the attack have been reduced because people have spoken out and organized acts of resistance. Cathy Crowe has long been one of the clearest and most consistent of those voices of opposition. As a long-standing OCAP organizer involved in many campaigns and actions against homelessness, I am painfully aware that if resistance has been far from futile, it has yet to emerge in a form and on a scale that can take the struggle from a defensive to an offensive undertaking. As A Knapsack Full of Dreams is put before us, the Ford government is busy making things far worse than they have been up to now. The homeless situation is becoming more dire with every passing month. The papers are full of accounts of global economic downturn. If the situation presented in Cathy’s book looks dreadful, the potential for things to become far worse is only too real.

In her chapter on homeless families, Cathy poses a question: “In every community across the country there are research reports chronicling that the fastest growing demographic of people becoming homeless is families with children. Such data illustrates that we know the economic, health, education and social costs of not providing affordable housing for people – so why aren’t politicians and governments stepping up?” Having posed this very important question, the chapter concludes with the simple observation that “[t]hey’re making other choices” (p.264). I feel, however, there is something that is missed here. Why are those socially destructive choices being made that consign families with children to homelessness?

In my view, the political system that places such decision makers in power is only a reflection of the fact that the society that it operates in is a capitalist one. Housing in such a society is not provided as a human right but is treated as a commodity, as the UN Special Rapporteur on the Right to Housing, Leilani Farha, has argued. Behind the politicians and their choices is a whole profit-making system operated by bankers, developers, landlords and speculators. It is their power you are up against and not merely the limited social conscience of ministers of the Crown. Cathy has certainly broken the rules in the course of her political nursing, but she very much presents this as a last resort, taken when the bad faith of those in power have forced her hand (p.315). I would rather view disruptive collective action as the best and primary means of gaining ground against a system that serves the interests of the very people who are responsible for homelessness. For housing to be really treated as a human right, we must change this society very fundamentally. In the shorter term, however, the political decision makers will have to weigh their loyalty to the vested interests against a social mobilization they have no choice but to take seriously. Cathy talks of “speaking truth to power” (p.294), but the bigger question is to develop a social power of our own.

Having offered those few respectfully critical observations, I conclude by saying that before this book could be written, Cathy the Street Nurse had to be forged out of long years of relentless and dedicated work. They have been years that have made a difference in many lives and laid the basis for the challenges to the social crime of homelessness that will be taken up in the years ahead. A Knapsack Full of Dreams is described by one invited commentator as a “deeply personal journey” and in some ways it is. However, it is also, in another sense, the property of all those who ask why destitution is allowed to exist alongside great wealth and want to challenge and defeat this great injustice. Cathy’s book should be read by all those who share this objective. •

A Knapsack Full of Dreams is available for purchase from Friesen Press. More information at cathycrowe.ca.