Tailings Dam Spills at Mount Polley and Mariana

Chronicles of Disasters Foretold

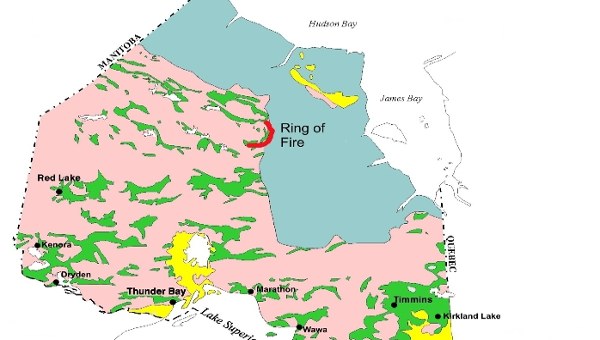

On August 4, 2014, the dam holding toxic waste from the Mount Polley copper and gold mine in the Cariboo region of British Columbia (BC) collapsed. More than 24 million cubic metres of metals-laden fine sand and water were spilled from the breached dam, creating the largest environmental disaster in Canada’s mining history. The spill flooded Polley Lake and flowed into Hazeltine Creek and Quesnel Lake. Land, water systems and salmon habitat were destroyed. The Northern Secwepemc people, on whose territory the mine was located, lost land, livelihoods and traditional uses integrally linked to the land.

On November 5, 2015, the Fundão tailings dam, an even larger reservoir of mine waste, collapsed at the Samarco iron mine in Mariana, Brazil. More than 32 million cubic metres of toxic tailings were spilled into the 853-kilometre-long Rio Doce (Sweet River in English) causing a tsunami-like wave of toxic muck that rapidly made its way through the states of Minas Gerais and Espírito Santo and out to the Atlantic coast. The Rio Doce basin is home to 3.2 million people.

On November 5, 2015, the Fundão tailings dam, an even larger reservoir of mine waste, collapsed at the Samarco iron mine in Mariana, Brazil. More than 32 million cubic metres of toxic tailings were spilled into the 853-kilometre-long Rio Doce (Sweet River in English) causing a tsunami-like wave of toxic muck that rapidly made its way through the states of Minas Gerais and Espírito Santo and out to the Atlantic coast. The Rio Doce basin is home to 3.2 million people.

The Samarco mine disaster is the largest in Latin American history. Nineteen people lost their lives, three nearby communities were buried and more than 1,200 people were left homeless. Communities located even hundreds of kilometres from the mine site lost their lands, crops, livestock, fishing livelihoods and water access. These included an Indigenous community of 400 Krenak people living on the remaining 4,000 hectares of their traditional land on the bank of the Rio Doce.

Canada and Brazil may appear to represent such markedly different jurisdictions that a meaningful comparison seems unlikely: Canada is understood as a rich, “developed,” politically stable nation in the Global North, while Brazil is located in the poorer, “developing” Global South, popularly understood to be endemically corrupt and politically unstable. Yet a closer look at the mining disasters at Mount Polley and Mariana immediately reveals remarkable similarities, not only in the contexts and circumstances leading up to the breaches but also in the corporate, governmental and civil society responses afterwards.

The Enormity of Tailings Ponds

Despite their name, tailings ponds are often more like lakes – many square kilometres in size, held in by dams that may be 40 to more than 100 metres high.

“Tailings” refers to the chemical-laden waste rock left behind from the processing of ore: in milling and separating ore from marketable minerals, a huge quantity of waste rock is ground to the consistency of sand and ends up mixed with a tremendous amount of water into a “slurry,” which is then piped into a tailings pond. The solids settle to the bottom of the pond and also form “tailings beaches” that become an important buffer between a pond’s embankment (waste rock set up to hold in solids) and the water. A dam at the outer perimeter of the embankment then serves as a failsafe when water levels rise – though over time, and without proper maintenance, dams may be weakened by erosion, crack and then fail, as was the case with Mount Polley and Mariana.

When the overfilled Mount Polley tailings dam failed, mining waste that included arsenic, lead, mercury, selenium and phosphorus, among other substances spilled into the surrounding forest and lakes. And when Samarco’s Fundão dam collapsed, waves of toxic muck buried three communities, partially damaged many others – killing 19 people and leaving hundreds homeless – and devastated the surrounding region and major waterways before making their way to the Atlantic Ocean.

A Tale of Two Breaches

In both cases, the mining companies had enjoyed a decade of rising mineral prices, during which they pursued aggressive expansion, sought more relaxed licensing and regulatory procedures, and quickly built more and bigger tailings ponds in order to capitalize on the boom. When the boom ended and commodity prices plummeted, both companies took measures to maintain their profit levels that included cost-cutting, reducing maintenance and inspections, filling tailings ponds beyond their designated capacities and ignoring warnings, recommendations and known structural flaws.

The corporate owners of both mines – Imperial Metals, owner the Mount Polley Mining Corporation, and Vale and BHP Billiton, joint owners of Samarco Mining – enjoyed close relationships with major political parties and government officials. The mining industry in both jurisdictions pressured governments to adopt their agenda on licensing, environmental safety and third-party inspections. And the companies in question donated generously to political parties, thereby giving elected officials a financial interest – and, since electoral campaigns are expensive, a political interest – in promoting the mining sector and prioritizing the needs of industry.

In each jurisdiction, governments streamlined review and approval processes, reduced oversight and eased regulatory requirements for energy and mining corporations (among others).

At the same time, in both Brazil and Canada, mining law and common operational practices carried vestiges of the countries’ histories of colonial occupation and the dispossession of Indigenous peoples. Indeed, at both Mount Polley and Mariana the mining companies impacted territories with Indigenous land claims, where spills would disproportionately impact Indigenous populations that, for practical and spiritual reasons, depended on the land, water and ecosystems in the surrounding areas.

Disasters Foretold

The Mount Polley and Mariana dam spills should be understood as symbols of the unregulated power of transnational corporations.

At both sites, numerous warnings about the security of the dams were ignored and mining companies were allowed to go ahead with production despite serious risks. In the case of Mount Polley, a 2010 inspection report identified problems including a crack in the perimeter wall of the dam that had gone unreported, broken instruments for measuring water pressure, and a failure to develop adequate tailings beaches. A 2011 review also pointed out glaring omissions in the Mount Polley Mining Corporation’s assessment of the potential impact of a discharge of wastewater, and the Corporation’s failure to develop a detailed monitoring or emergency plan.

Despite this, after the dam collapse, Imperial Metals president Brian Kynoch was widely cited as saying, “If you asked me two weeks ago if this could have happened, I would have said it couldn’t.”

In the case of Mariana, a 2012 inspection into the possibility of unauthorized alterations to the Fundão dam identified a partial rupture that presented a severe structural risk and required more repairs than were being undertaken. In 2014, the same inspector also recommended the installation of additional instruments to measure water pressure (piezometers), but no such thing was done.

Further, like the Mount Polley Mining Corporation, Samarco Mining also failed to prepare for potential emergencies. A plan for monitoring and emergency procedures had been drawn up in 2009 – including a dam monitoring protocol, warning systems and emergency evacuation drills – but then iron prices fell, the company sought to cut costs and the plans were shelved. As a result, there was no advance warning when the Fundão dam collapsed, even for communities hit by toxic muck 14 hours after the breach.

At both mines, the companies’ failure to act on warnings and prepare for possible disasters point to an alarming corporate practice of putting production and profit ahead of safety considerations. It also raises serious questions about governments’ ability to challenge the power and impunity of the global mining industry, and its willingness to govern in a manner that actively protects the environment and the rights of its citizens – economic, social, cultural, Indigenous and universal human rights.

Moving Forward

After scrutinizing the events leading up to the breaches, it would seem that they are, indeed, chronicles of disasters foretold – with more in the offing.

A study of more than 40 years of tailings incidents (conducted for AMEC Earth and Environmental) suggested that the frequency of incidents can be expected to increase in the 24 to 36 months after market booms. And a report from the panel investigating the Mount Polley incident found that “if the inventory of active tailings dams in the province remains unchanged, and performance in the future reflects that in the past, then on average there will be two failures every 10 years and six every 30.”

This is not to mention the chilling fact that only seven months after the Mount Polley disaster, long before investigations into the disaster had concluded, Imperial Metals applied for a permit to restart the mine. Similarly, an application for the reopening of Samarco was filed before assessments of damages were complete, and while clean up and reparations were still underway.

Clearly, fundamental challenges still lie ahead in tackling the mining industry’s current power and impunity. Some of these challenges are being addressed by Indigenous leaders, social movements, NGOs and institutions such as churches, unions and universities, which have been critiquing mining company behaviour, supporting the emergency relief needs and compensation claims of those who lost lands and livelihoods because of the breaches, and producing numerous public policy recommendations. In Canada, the University of Victoria’s Environmental Law Centre called for a Judicial Inquiry on BC mining regulation, for which an urgent need was established in the March 2017 study the Centre prepared for the Fair Mining Collaborative. The Centre’s call portrayed a provincial mine regulatory system in a “state of profound dysfunction.”1 Amnesty International’s study of rights violations linked to Mt. Polley also called for a public inquiry and release of information from impact studies. At the international level, the UN Environment Programme carried out a “Rapid Response Assessment” focused on mine tailings storage, with Mariana photos on the cover and a Mt. Polley case study in the contents.2 UNEP made detailed recommendations on better tailings management that give priority to safety and called for the establishment of a UN Environment stakeholder forum on tailings dam regulation.

However, we must also address the context of “regulatory capture,“ which occurs when regulation, or the carrying out of regulatory oversight by a government body, is directed or unduly influenced by the private industry subject to regulation. The process of capture involves not only lobbying, political contributions and “revolving doors” between government and corporate leaders, but also the advancement of a narrative that blurs the distinction between corporate interests and what is genuinely in the public interest.

The BC government has recently taken important steps in three key areas. First, it has committed to implementing the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) and the calls to action from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Second, the government introduced a ban on corporate and union political donations, which cuts off the large stream of money flowing to political parties from mining and other extractive industry groups. And third, the government has undertaken a review of the model that allows resource companies to hire “qualified professionals” to review proposed projects instead of public officials. Whether the mining industry’s power and the problem of regulatory capture in BC are significantly curbed remains to be seen. Notably, the government has been silent on a central recommendation from the Auditor General of BC stemming from an investigation into the government’s compliance and enforcement activities in the mining sector: to address the conflict of interest inherent in a model where the same government body (the Ministry of Energy and Mines) is tasked with both promoting mining and regulating it. To date, there is no independent compliance and enforcement agency for mining – and lobbying activities by the mining industry continue without limitation. If regulatory capture continues, who will speak for workers and communities, for land, rivers and the salmon? The challenge now is ultimately one of political will. •

This report was first published jointly by the Corporate Mapping Project, CCPA–BC Office, PoEMAS (Grupo Política, Economia, Mineração, Ambiente e Sociedade) from Brazil and the Wilderness Committee. The paper is part of the CMP research and public engagement initiative investigating the power of the fossil fuel industry. The CMP is jointly led by the University of Victoria, the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives BC and Saskatchewan Offices and the Parkland Institute. This research was supported by the Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC).

Full study: corporatemapping.ca/tailings-disasters

Summary in Portuguese.

Endnotes

- Environmental Law Centre, Request for Establishment of a Judicial Commission of Public Inquiry to Rectify and Improve BC Mining Regulation, March 8, 2017.

- Roche, C., Thygesen, K., Baker, E. (Eds.), Mine Tailings Storage: Safety Is No Accident, A UNEP Rapid Response Assessment, 2017.