Public Ownership for Energy Democracy

Opportunities for Publicly-run Energy Utilities to Revolutionize Generation and the Grid

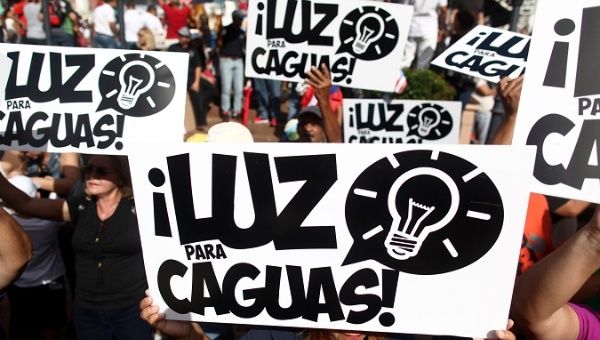

Energy democracy – a new idea from the ranks of community organizers, labour, and renewable energy advocates who see our current energy system as broken and destructive – seeks to take on the political and economic change needed to tackle the energy transition holistically. A democratic energy system powered by renewables (and free of fossil fuels) would distribute wealth, power, and decision-making equitably. But, practically speaking: How can we redesign our energy system with energy democracy at its core?

A first step is to stop exploiting fossil fuel reserves, as Quantitative Easing for the Planet proposes. Another imperative is to shift ownership of the generation, transportation, and distribution of energy. Restructuring and democratizing our electric systems through public ownership – whether government or cooperative – can help transition the United States away from fossil fuel production and toward a renewable future built with communities in mind instead of profits.1

A first step is to stop exploiting fossil fuel reserves, as Quantitative Easing for the Planet proposes. Another imperative is to shift ownership of the generation, transportation, and distribution of energy. Restructuring and democratizing our electric systems through public ownership – whether government or cooperative – can help transition the United States away from fossil fuel production and toward a renewable future built with communities in mind instead of profits.1

Public ownership of utilities can accelerate the renewable energy transition at the scale needed to meet our closing climate deadline for action. It’s simply too late to provide piecemeal incentives and then wait expectantly for a market controlled by fossil fuel interests to voluntarily deploy more renewables. Energy utilities’ control over so much of the energy supply chain make these entities a strategic platform for bringing energy democracy tactics to scale. Harnessing energy utilities for the people could fuel projects from expansive low-income housing efficiency projects (such as PUSH Buffalo),2 to community solar programs (such as the solar gardens of Cooperative Energy Futures in Minnesota),3 to stopping gas pipelines (such as the resistance to Dominion Power’s Mountain Valley Pipeline in Virginia).4

Public ownership of energy is nothing new in the United States. American communities have exercised the right to own and operate a municipal utility since the 1880s. In the 1930s, a federal loan fund for rural electrification started, and farmers ignored by for-profit utilities banded together to create rural electric cooperatives to serve their communities.5 Publicly-owned utilities now serve cities as small as Hammond, Wisconsin and as big as Los Angeles and Nashville. In Nebraska, only publicly-owned utilities are allowed to operate.6 Still, some of these utilities lack the ample democratic oversight or access to investment needed to become effective envoys for energy democracy.

Centering Public Ownership On Energy Democracy

Public ownership is poised to subvert the current energy paradigm, but the institution must first transform to center on a rapid transition to renewables, deep democratic governance, and equitable distribution of wealth – both embodying and promoting energy democracy.

Electricity generation makes up about 40 per cent of all energy use and currently relies heavily on fossil fuels. Both investor-owned and publicly-owned utilities have vested interests in fossil fuels. For example, rural electric cooperatives still rely on coal, oil, and gas for 90 per cent of their generation.7 They have also similarly made dubious decisions on where to dump toxic byproducts from the extractive process, like coal ash.8 However, publicly-owned utilities don’t have the same motivations and incentives to continually expand energy production since they don’t have to generate a profit for shareholders. This freedom gives them more flexibility to respond to their customer-owners’ needs, as their charters require (either directly or through elected representatives). Therefore, a publicly-owned utility is more likely to yield to public pressure to eliminate fossil fuels than investor-owned utilities. Furthermore, if a publicly-owned utility shift came at the same time as a sweeping buyout of the fossil fuel industry (see “QE for the Planet”), it could help catalyze the shift.

Given their purpose and lack of any imperative for growth, publicly-owned utilities could be major players in the rapid expansion of decentralized energy – from individual solar to community wind farms. What’s more, renewable-energy projects financed by local municipal utilities could be deployed on a larger scale since municipal bonds afford them cheaper access to capital than companies or individuals enjoy. Tax-exempt municipal bonds have financed $96-billion in new public utility investments over the past decade. By involving the community in the process of renewable energy projects and sourcing related jobs locally, utility-financed projects could build community wealth. In other words, economic development would localize investment and provide broad-based ownership. Considering publicly owned utilities’ sunk investments in infrastructure like natural gas plants, transitioning toward a renewable energy system will still take time and require active community participation, investments to alleviate the burden of stranded assets, and increased investments in renewables.

Democratic Governance

Right now oligarchic for-profit utilities make decisions about most of the power grid, based on their vested interest in the energy status quo and the need for shareholder profits – not the common good. Frequently, such decisions are made far from the communities where their repercussions play out.

Regulators across the country also bend to the powerful influence of the wealthy industry they regulate. For instance, a burst gas pipeline in California in 2010 exposed an all-too snug relationship that allowed lax implementation of safety standards between California for-profit utility, PG&E, and its regulator – with devastating results both for neighborhoods along the spill’s path and for climate generally.9 In Texas, the Association of Electric Companies of Texas met privately with state regulators to revise pollution permits that nullified the Clean Air Act for their coal plants. Documents later revealed that regulators implemented new environmentally devastating regulation lifted verbatim from trade group proposals. This type of corporate capture has left people feeling unheard and unprotected.

In contrast, community members served by a publicly-owned utility act as owners and decision makers. Instead of controlling large swaths of the country that may not even be contiguous, publicly-owned utilities are rooted to place – owned and operated by their community. Although publicly-owned utilities reflect democratic principles, in practice some still suffer from a lack of community representation. For instance, a 2016 survey of over 300 rural electric cooperatives in Southern states showed that only 90 of more than 3,000 board members were Black residents. Structural problems like racism and sexism, in turn, can destroy community spirit and create power imbalances. In contrast, reorienting utilities toward democratic governance for the 21st century would redistribute power by giving communities more energy decision-making opportunities.

One such mechanism is the multi-stakeholder board where elected workers, community members, and local officials make decisions together. Switched On London, a campaign for a municipal utility, proposes a governing Board of Directors composed of one third London public officials, one third energy company employees elected by the company workforce, and one third ordinary London residents – regardless of citizenship – elected by peers. Half of all positions must be held by women.

Participation should go beyond representative systems of democracy. Opportunities for direct engagement should span such institutions as public forums, neighborhood assemblies, and online engagement. For example, the municipal utility in Cadiz, Spain set up a bimonthly roundtable where it invites environmental advocates, community members, experts, and businesses to discuss milestones toward 100 per cent renewable energy.10

To substantiate opportunities for direct engagement and rid the publicly-owned system of vestigial self-serving interests or elitism, utilities need to make decision-making and operations transparent and accessible. Since the energy sector tends to be technocratic, eliminating communication barriers and using straightforward language are crucial for equipping community members to engage in decision making. Accessible information is not enough though. Communities will have to grapple with their specific barriers to participation – from lack of accessible public forums to exclusive decision-making structures. For instance, attending public forums during the day can be highly prohibitive to those community members who work in inflexible circumstances.

Equitable Distribution of Wealth

Currently, low-income neighborhoods and communities of color without political or economic influence shoulder the burden of energy infrastructures’ negative consequences and pay more for energy because their housing stock is old and inefficient. These people and places will be hurt the most by climate change’s extreme weather events. To make such inequitable burdens things of the past, we need to de-consolidate power, make extraction unprofitable, and redistribute wealth and ownership in the energy economy while providing a just transition for workers in the current energy industry. Investor-owned utilities’ prime motivator is consolidating wealth as a for-profit company, whereas those owned by the public are designed to serve the public. Below describes some of the important ways to distribute wealth equitably in a new energy era, investigating how publicly-owned utilities may already give back to their communities as well as additional strategies to better deliver.

Renewables Ownership

Although publicly-owned utilities don’t have to worry about turning profits, like for-profits, they historically rely on centralized energy systems and therefore are reticent to have their investments eroded by self-sufficiency through decentralized renewable energy use. In contrast, a strategy based on energy democracy should deliver renewable energy locally to the extent possible and insist on broad ownership – both individual or community-owned decentralized renewable energy and larger, utility-scale projects run by and within the municipality. Publicly-owned utilities will need to identify ways to balance centralized energy with a more decentralized grid.

When renewable energy is kept local, the economic returns to the community grow apace. Every megawatt of locally installed solar can add $2.5-million and 20 construction jobs to the local economy. Locally owned projects can redirect an additional $5.4-million of electricity spending locally over the project’s 25-year lifetime. More particularly, the utility should get low-income residents’ and communities of color’s input and participation in rate design, financing, local job training and hiring, capacity-building, and the like for renewables projects. These energy consumers have customarily had the most to gain from, but the least access to, energy ownership’s benefits. Strategies could also involve anchor institutions – such large-scale nonprofit entities as hospitals and universities, which are both big energy users and major recipients of substantial public resources. This approach would meet these institutions’ energy needs, build jobs, and help finance and provide space for community renewable projects.11

Distribution of Wealth

Investor-owned utilities put the wealth of their stockholders and executives first. The CEO of FirstEnergy, for instance, makes 131 times the average lineman’s salary.12 In contrast, money made by a publicly-owned utility doesn’t make the rich richer. Revenues are instead reinvested in such public goods as lowered costs and increased service quality for consumers, in efficiency upgrades for low-income households, or (for municipally-owned) in local schools and bridges through the city’s General Fund. Publicly-owned utilities contributed around 6 per cent of their revenues to local government in 2016, according to an American Public Power Association study – 27 per cent more than investor-owned utilities often paid in taxes. Some such city-bound revenues could be taken to the next level and even fund, say, a city Green Bank that could in turn support energy-efficiency upgrades for low-income housing or finance decentralized renewable energy within the community.

Energy Poverty

In some areas of the United States, low-income households pay around 35 per cent of their income for energy, forcing painful choices between a heated home and food on the table. Multiple utilities have become known for increasing their rates to make more profits.13 Overall, publicly-owned energy has been proven to be cheaper than for-profit power across the United States. While a positive trend, however, lower rates don’t always mean less energy poverty. Instead, fair rates should come alongside robust and low-cost opportunities for energy efficiency projects and renewable ownership opportunities to cut the energy burden, disproportionately felt by Black or Latinx residents. A public utility could also cap the percentage of anyone’s income spent on their bills and eliminate energy cutoffs altogether. For example, Ohio, which has the nation’s largest and oldest Percentage Income Payment Plan (PIPP), limits any one person’s bill to 10 per cent of their household income. Access to energy is a human right, and nobody should be forced to choose between risking heat stroke or hypothermia or staying hungry.

A Just Transition

In the fight against fossil fuel infrastructure, unions and utilities have often been on the same side. Unions fear that their members will be left jobless if the industry declines. In fact, they – not executives and shareholders – will bear the brunt if strategies are not implemented now to make the transition ahead work for them. Although imperiled by a mid-2018 Supreme Court decision making unions’ “agency fees” optional for public union members, the tradition of stronger unionization within the public sector14 opens the possibility of working with unions to phase out current fossil fuel jobs and provide better, long term jobs in the reinvented energy sector. Adding participatory structures that give workers’ more say can ensure that workers shape the transition, not get left behind.

Job creation is also on the energy democracy horizon. The massive investment needed for a new energy system could create huge numbers of jobs over the short and long terms. Publicly-owned utilities should establish robust labour practices as major players building and installing renewable energy and set the standard for job quality. They can also bridge the inequality gap by training and empowering the low-income and racial minority populations most harmed by climate impacts and underemployment.

Job creation is also on the energy democracy horizon. The massive investment needed for a new energy system could create huge numbers of jobs over the short and long terms. Publicly-owned utilities should establish robust labour practices as major players building and installing renewable energy and set the standard for job quality. They can also bridge the inequality gap by training and empowering the low-income and racial minority populations most harmed by climate impacts and underemployment.

A Two-Pronged Strategy

A two-pronged strategy for public ownership could simultaneously harness the opportunity of public utilities to champion and accelerate energy democracy, while also taking for-profit utilities into community hands to reorient their focus toward the public good.

Today, publicly-owned, democratically governed electrical utilities serve 28 per cent of all U.S. customers.15 More agile and accountable, communities have more leverage to prompt wider shifts toward equitable renewables at these municipal utilities and rural electric cooperatives faster than what it possible with investor-owned utilities. To do so means transforming the institutions so they better deliver on the values of energy democracy – such as better democratic procedures and equitable access to services.

A vibrant movement is already under way to reshape these publicly-owned energy utilities so that they operate for the people, by the people. Groups like Nebraskans for Solar have campaigned hard to shift the largest utility in Nebraska’s publicly-owned electricity system toward larger renewable uptake. Running campaigns on green platforms, community organizers ousted incumbents, put teeth in sustainability directives, and, by tapping local wind farms, renewable energy is forecasted to provide over 40 per cent of total use by 2019.16 One Voice Electric Cooperative Leadership (ECLI) in Mississippi has worked for greater participatory democracy in rural electric cooperatives, supporting Southern Black and minority owner-members in historically racially segregated cooperatives and reversing miseducation.

At the same time, through municipalization we need to take back those large swaths of our energy system captured by investor-owned utilities. These for-profits have employed many tactics to derail municipalization campaigns, particularly by discrediting publicly-owned power as inefficient or costly and spending millions of dollars to bankroll anti-municipalization efforts. Often, these scare tactics lack any factual basis. For instance, publicly-owned utilities consistently provide lower – not higher, as claimed – rates today than their for-profit counterparts.

This onslaught can be beaten back. Xcel Energy spent $1.7-million in local Boulder elections to stop the city’s energy-municipalization campaign between 2011 and 2013 – ten times what citizen advocates spent.17 Even with all that cash, Xcel Energy is losing the local political battle, and Boulder has a clear path toward municipalization. A small but growing movement is fighting these utility Goliaths for public ownership.18 In the process of ousting their unresponsive, and destructive, for-profit utility, communities can design their utility from the ground up with energy democracy as the taproot.

Conclusion: Realizing Public Ownership’s Full Potential

Public ownership could usher in a foundational part of the next energy system and support energy democracy at a large scale in the United States through decentralized renewable energy adoption, deep democracy, and re-distributed wealth. The power we already have could be better leveraged, public ownership of utilities could be expanded, and our energy future could be removed from for-profit hands. Energy generation and distribution are key pressure points in wresting control of energy supplies from fossil fuels and backing renewables – and public ownership could make that transition a reality. •

This article first published on the Thenextsystem.org website.

Endnotes

- Andrew Cumbers, Reclaiming Public Ownership: Making Space for Economic Democracy (New York, NY: Zed Books, 2012).

- “Connecting People to Energy and Power,” PUSH Green, accessed July 27, 2018.

- “Cooperative Community Solar Gardens Building Equity in Our Energy Future,” Cooperative Energy Futures, accessed July 27, 2018.

- Olivia Rosane, “Court Orders Controversial Pipeline to Halt Construction Over West Virginia Streams and Wetlands,” EcoWatch, June 26, 2018, accessed July 30, 2018.

- “The Story Behind America’s Electric Cooperatives and the NRECA,” America’s Electric Cooperatives, accessed July 27, 2018.

- Keisha Patent, “Public Power in Nebraska,” Legislative Research Office, January, 2018.

- “2017 Directory and Statistical Report,” Washington, D.C.: American Public Power Association, 2017.

- Steven Hale, Steve Cavendish, “TVA, Coal Ash Pollution on the Cumberland River: a federal lawsuit targets environmental mess at TVA’s Gallatin plant,” Nashville Scene, January 19, 2017, accessed August 21, 2018.

- “Not so fast on PUC ‘reform’,” The Times Editorial Board, Los Angeles Times, February 19, 2016, accessed July 27, 2018; Thomas Lee, “San Bruno Explosion Hangs over PG&E Amid Wildfire Investigation,” San Francisco Chronicle, October 21, 2017, accessed July 27, 2018.

- Alba del Campo, “Energy Tables in Cádiz, Spain,” Energy Democracy, April 4, 2018, accessed July 27, 2018.

- For more information, see “An Anchor Strategy for the Energy Transition.”

- Using Glassdoor Average Lineman Salary: $66,680 (“Lineman Salary,” Glassdoor, July 30, 2018, accessed August 1, 2018); “Charles E. Jones,” Salary.com, accessed July 27, 2018.

- Ryan Handy, “CenterPoint wins rate hike as profits rise past state cap,” Houston Chronicle, May 31, 2017, accessed August 21, 2018; Thea Riofrancos, Robert Shaw, and Will Speck, “Ecosocialism or Bust,” Jacobin, April 20, 2018, accessed August 21, 2018.

- Union membership rate of public sector workers is 34 per cent, five times higher than that of the private sector workers at 7 per cent (“Union Members Summary,” Bureau of Labor Statistics, January 19, 2018, accessed August 8, 2018).

- We consider rural electric cooperatives “publicly-owned” since ownership is dispersed between members.

- Cole Epley, “Wind power will generate 40 per cent of OPPD’s electricity by end of 2019,” Omaha World Herald, July 17, 2017, accessed July 27, 2018; Interviews with Omaha and Nebraska community organizers and officials, October, 2017.

- Alex Burness, “After Spending $1.7M opposing past Boulder utility campaigns, Xcel vows to stay out of one,” DailyCamera, September 21, 2017, accessed July 27, 2018; “Why Is Xcel Trying to Block The Muni At Every Turn,” Empower Our Future, accessed July 27, 2018.

- John Farrell, “Vote for Decorah Municipal Utility Falls Short, But Local Energy Advocates Persist,” Institute for Local Self-Reliance, May 31, 2018, accessed July 27, 2018; “PUD History,” Jefferson Public Utility District, accessed August 8, 2018.