Arshiya Chime is a union member helping to rescue the world from climate change. Once she gets her doctorate degree later this year from the University of Washington, she will become a highly prized mechanical engineer, helping economies become less dependent on oil while protecting the environment and creating jobs. But Chime, a leader in her graduate student employees union, United Auto Workers Local 4121, is not welcome in Donald Trump’s vision of America. As an Iranian immigrant, she’s denied the right to freely travel. If Trump’s Muslim travel ban orders ultimately are upheld, Chime would probably have to take her expertise to another country, because U.S. firms won’t want to hire someone unable to work on foreign projects and attend international conferences.

Chime is not alone. About 30 per cent of her fellow graduate student employees at the University of Washington are international students, many of them from countries included in the Trump travel ban. When the White House announced the ban in late January, Chime’s union rallied with other labour groups, immigrant rights organizations, faith allies and political activists, staging impromptu airport mass marches and shutdowns. Chime and other UAW 4121 leaders mobilized public opinion[1] by speaking out at press conferences, organizing teach-ins, and by joining the lawsuit that ultimately blocked Trump’s ban.

Chime is not alone. About 30 per cent of her fellow graduate student employees at the University of Washington are international students, many of them from countries included in the Trump travel ban. When the White House announced the ban in late January, Chime’s union rallied with other labour groups, immigrant rights organizations, faith allies and political activists, staging impromptu airport mass marches and shutdowns. Chime and other UAW 4121 leaders mobilized public opinion[1] by speaking out at press conferences, organizing teach-ins, and by joining the lawsuit that ultimately blocked Trump’s ban.

Other union leaders, unfortunately, seem to have forgotten the picket line refrain, “an injury to one is an injury to all.” The same month, but a political galaxy away from the boisterous airport demonstrations, construction union leaders exited an Oval Office meeting to rave about the new president’s pledge to boost infrastructure spending. “We have a common bond with the president,” gushed Sean McGarvey, head of North America’s Building Trade Unions.[2] AFL-CIO President Richard Trumka praised Trump for talking up jobs in his first joint congressional address[3] and could barely manage a milquetoast riposte[4] to Trump’s xenophobic attacks on people like Arshiya Chime.

The divergent labour reactions frame the stark choice facing the U.S. union movement: build fighting working class solidarity, or a hunker down in a desperate every-union-for-itself strategy.

Today’s situation is perilous. Unions represent barely 10 per cent of the U.S. workforce, down from 33 per cent in the 1950s. Union leaders across the political spectrum are quick to pin blame for the present crisis on relentless union-busting and hostile politicians. That’s accurate – but not a complete explanation. Corporate America’s insatiable profit drive is only half of our problem; the other half is the movement itself. The disastrous situation didn’t materialize overnight. Rather, the seeds of today’s ruinous harvest were planted 70 years ago.

An Era of Union Complacency

By the end of World War II, U.S. union membership had soared, reaching a third of all workers. In manufacturing, fully 69 per cent of production workers were covered by union agreements. Militant strikes during and right after the war pushed demands for a greater share of the economic pie along with social demands like price controls. In 1946 alone, 4.6 million workers went on strike – about 1 in every 20 in the paid U.S. workforce.

But rather than build on that nascent power, most union leaders determined to make peace with political and business elites, believing – incorrectly – that the tripartite domestic détente of World War II was still alive. Even before Senator Joe McCarthy’s witch-hunts, unions started purging communists and other suspected radicals from their ranks, seeking to demonstrate their loyalty to government and business.

The leadership of the labour federation that emerged in the 1950s steered away from organizing more workers. AFL-CIO president George Meany famously declared, “I used to worry about the size of the membership. I stopped worrying because to me it doesn’t make any difference. The organized fellow is the only fellow that counts.” Most union leaders focused on securing economic gains for their largely white membership, tamping down militant insurgency in the ranks, giving lip service to the emerging civil and women’s rights movements, and pledging allegiance to the capitalist economic system in exchange for collective bargaining agreements.

The bargaining system has worked well overall for those fortunate to be covered by union contracts. By the new millennium, the average union member could expect to make 25 per cent more than a worker not covered by a union contract. But flip side of this ‘union difference’ was that it presented a huge incentive for corporate and political elites to attack labour’s power through union-busting, outsourcing, contracting out, and passing laws to hamstring unions.

As union power ebbed and the American Dream of upward mobility slipped away, most union leaders – instead of organizing to expand their membership – clung reflexively to the Democratic Party for salvation. In 1976 they backed Jimmy Carter for president, expecting to win labour laws to ease organizing. Instead, Carter and an overwhelmingly Democratic Congress handed corporate America deregulation tools to dismantle worker power and slash pensions. In 1992 unions counted on Bill Clinton to deliver jobs, but instead he pushed the job-killing North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and eviscerated the nation’s welfare system. Even as workers became more productive, real wages stagnated. In 2008 unions hoped Barack Obama would save workers but instead Wall Street got bailed out while nearly 9 million workers were fired, 14 million families lost their homes, and the president invested more political capital in promoting another horrible trade agreement – the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) – than in backing modest labour law reform or a raise in the national minimum wage.

Under Obama, union ranks have declined by another half a million workers, and U.S. inequality has reached epic levels. Given that record, it’s no surprise that the 2016 election produced the most anaemic union turnout for a Democratic presidential candidate in more than 30 years: Hillary Clinton won union households by only 51 to 43 per cent, an 8 per cent margin. In the previous seven presidential elections, the Democrat won union households by an average margin of 22 per cent.

Now, quite a few leaders on the left are advocating that unions and their allies try once again to reform the national Democratic Party from within. This is a fool’s errand, as the recent installation of an establishment, pro-corporate party chair underscored.[5] If there’s any single takeaway about working class voters in the 2016 campaign – from Bernie Sanders’s remarkable insurgency to Donald Trump’s brutal and ugly win – it’s a rejection of the establishment of both major political parties.

Likewise, the AFL-CIO’s Trumka and the construction union heads who today seek common ground with Trump are repeating the historic mistake of believing that sworn enemies truly want accommodation with labour.

Social Movement Unionism in Ascendance

The salvation of unions resides in joining with allies to fight the coming Trump onslaught – and then to go beyond that to define a bold, unapologetic vision of society and economy, one that inspires millions of workers to engage and take action.

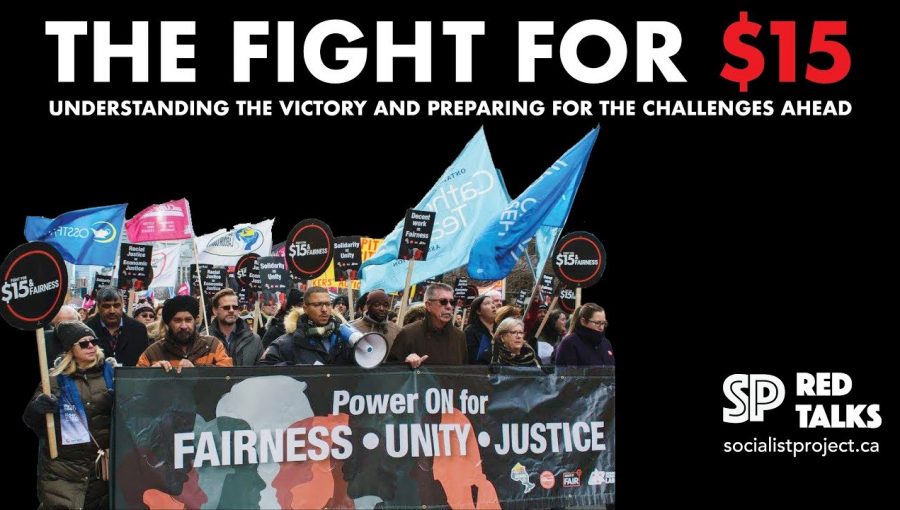

For those of us in unions, it means using all of the tools at our disposal to defend what we still have – at the bargaining table, on the shop floor, and in legislative halls – but then go beyond to forge new powerful community alliances to demand civil rights, immigrant justice, healthcare, quality education, food and shelter, and fair wages for all. Indeed, the pinnacle achievements of U.S. unions – think Social Security, minimum wages, safety laws – took place when labour acted not out of narrow self-interest, but as part of a broad social movement; not as a co-dependent of a political party, but as an independent force.

In other parts of the world, particularly among societies in the global south, such formations are called social movement unions: Bold movements that recognize the singular nature of the justice fight spanning workplace and community, and the inseparability of economic, racial, and social justice struggles.

The elements of social movement unionism already are among us, embedded in leading justice struggles today.

- Chicago teachers, uniting with parents, have struck to defend quality public education from corporate attack.

- Uber and other rideshare drivers have organized strikes to win better pay and protections.

- Outside Seattle, a coalition of low-wage immigrant airport workers, faith activists, and community members took on an improbable battle against corporate and political giants to win a breakthrough $15 ballot initiative, helping to spark a national movement (I was privileged to have been the campaign director).

- Undocumented immigrant labourers, housekeepers, and nannies have formed worker centres in dozens of cities around the country, leveraging wage standards and basic rights through collective action.

- In North Carolina and beyond, the Rev. William J. Barber II has united faith leaders, union members, and immigrant rights activists in a powerful Moral Mondays movement to reclaim democracy and raise the call for a moral economy.

- And, of course, there is Arshiya Chime’s union and the thousands of workers, faith and community activists who occupied airports nationwide and turned back Trump’s Muslim ban.

Indeed, the basis of social movement unionism rests on the simple and time-tested premise that, as Chime notes, ‘we are all in this together’. In the wake of the mobilizations against Trump’s travel ban, Chime saw her fellow Iranian students step up their union activities. They’d experienced the power of solidarity, and gained confidence through direct action.

These and other fledgling examples of social movement unionism understand that the fight is about power, that we need to build broad alliances of the 99 per cent, disrupt convention and circumvent broken law, and employ bold new strategies. And, importantly, each of these campaigns challenges unions to think differently about their role in the world – to act expansively, to link arms with new friends, and to articulate a bold vision of justice.

Indeed, the gift that Trump’s ascension gives us – perverse as that may sound – is that his victory strips away any illusions about the depth of organized labour’s existential crisis. The challenge within the U.S. labour movement is to shrug off past failed strategies and seize the moment to reclaim labour’s larger social purpose. •