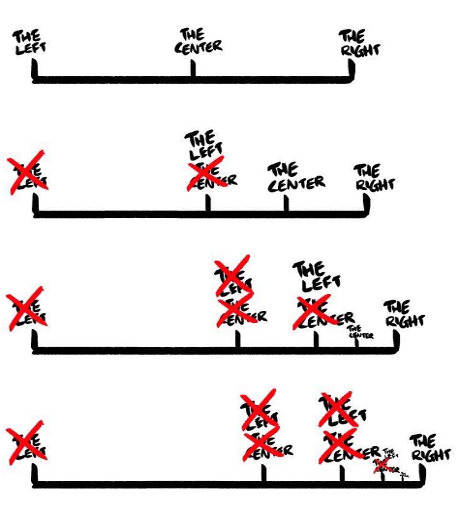

We live in a paradoxical world. Much debate on the radical left revolves around multitudes of discontented groups – sometime lumped together as the 99%, sometimes rebranded as precariat – struggling against an abstract empire and its 1% rulers. Capitalism and class – once serving as a compass to navigate left politics through the apparently chaotic sees of everyday life – have turned into subjects of theoretical debate with little to no connection to political praxis.

Vacated by the left, a new right adopted the language of class to appeal to those who were steamrolled and marginalized by economic globalization. Many of the policies advanced by the new right could have been taken out of social democratic programs of old but are now

Vacated by the left, a new right adopted the language of class to appeal to those who were steamrolled and marginalized by economic globalization. Many of the policies advanced by the new right could have been taken out of social democratic programs of old but are now

loaded with claims to racial and national superiority. Some on the left, and pretty much everybody in the political centre, takes the new right ideology at face value and concludes that working class politics, even if originally meant as harbinger of universal human liberation, invariably lead to nationalism and racism. Such reasoning ignores that much of the discontent on which the new right thrives is produced by neoliberal globalization, the very project that appropriates left aspirations of human liberation in the pursuit of profit.

It also ignores the fact that most of the support for the new right does not come from people with low incomes and little educational attainment but from the middle-brackets of Western societies. People at the low-end rather opt out of casting their votes. The franchise

for which socialists fought so hard at various points in history is increasingly abandoned by the have-nots whose ancestors still thought the sheer number of their votes might counterbalance the power of concentrated capital.

Dormant: Class Politics from Below

That class politics is dead, or at least dormant, doesn’t mean there are no political and social conflicts. In fact, there are a lot and most of them are fought out in the shadow of social democracy. The demands put forward by political upstarts like Podemos in Spain and Syriza in Greece, who grew out of the post-class politics of occupied public spaces, would have been considered as social democratic mainstream back in the 1970s. The same is true for Jean-Luc Mélenchon‘s presidential campaign in France or Jeremy Corbyn‘s efforts to put social democratic content back into the British Labour Party. And it is also true for a whole number of left-wing parties all over Western Europe. Some, like the Swedish Left Party, have roots in Soviet Communism, the Dutch Socialist Party comes out of the Maoist movement, and Ireland’s Sinn Fein out of the struggle for national independence. Back in the 1970s, all of these organizations were more or less critical of social democracy but began filling the vacuum left when social democratic parties, spearheaded by New Labour’s Tony Blair, began deserting the political space they had occupied throughout the post-WWII-era. To the Blairites and others in the political centre, a continued commitment to social reforms and the welfare state, not to speak of further reaching goals of socialist transformation, is not only a step toward the convergence with the populism coming from the new right. It is also seen as an expression of nostalgia unable to come to terms with the new realities of global capitalism.

This nostalgia charge contains a kernel of truth but misses the point. Widespread nostalgia has nothing to do with anyone’s inability to understand the harsh realities of global capitalism. It has anything to do with growing numbers of people resenting these realities and looking for alternatives. Ironically enough, social democratic parties abandoned their commitment to social reform and welfare state expansion at some time during the 1990s when the neoliberal promise of a rising tide that would eventually lift all boats began to ring hollow. With more and more people finding out that they were at the losing end of neoliberal globalization the welfare state regained popularity, which – under conditions of near full employment up until the 1970s – had been challenged by women, ethnic minorities and youth who resented their exclusion from welfare state provisions as much as the bureaucratic ways such provisions were delivered.

Yet, with the collective bargaining power of unions receding in the face of automation, relocations and the reorganization of firms and labour processes, inequality and insecurity began to rise. Under these conditions welfare states, despite cuts and even stricter bureaucratic control, became more important to increasing numbers of people who could have done without many of the welfare state’s provisions in the good old days of high employment and rising real wages. Memories of those days, even if they appear rosier in hindsight than they were experienced at the time, seem to be an inspiration for current struggles against further welfare state retrenchment. They can also contribute to the imagination of a better future.

Forward and Backward Looking Memories

In fact, ‘forward-looking memories’ did play key roles in the making of socialist movements in the past. The moral economy shaped by pre-capitalist agriculture and artisan production turned into a guide to struggle against the factory regime under which the first generations of wageworkers had to toil. Later, the traditions of craftsmanship inspired workers fighting against the degradation of work under the guise of scientific management and developed visions of workers’ councils and self-management out of these traditions. There is no reason that memories of more generous welfare states couldn’t inspire visions of a future beyond ever tighter budget constraints and bureaucratic control under which welfare states suffer at the present time. Unlike the memories of pre-capitalist times and craftsmanship, which motivated workers to build movements focused very much on the point of production, memories of the heyday of welfare state expansion open the focus to the much wider world of social reproduction. This could be a starting point of amalgamating movements organizing around specific issues – such as minimum wages, public healthcare, housing or education – into a more unified movement, which, in Marx’s and Engels’ words in the German Ideology, “abolishes the present state of things.”

Such a vision for the future doesn’t automatically develop out of memories of a better past. It needs to be actively created. This requires political interventions that allow people to see their past in a way that opens prospects for a better future. Without such prospects, ‘backward-looking memories’ can lead to a demoralizing and demobilizing yearning to restore an irredeemable past. The frustrated recognition of the impossibility to restore the past may then open the door to right-wing praise of the glorious past of the chosen people. Falling for such praise inevitably leads to frustration as this ideological cover stands in stark contrast to the politics that new right formations pursue. Rather than offering alternatives to an unloved present, these formations aim at the further radicalization of neoliberalism. Avoiding a vicious cycle of right wing policies thriving on backward-looking memories, further radicalization of neoliberalism and frustration fueled by the outcomes of such radicalization requires not only the opening of future prospects for a better world. It also requires an understanding why better conditions that existed in the past ceased to exist. In this particular case, this means an understanding of social democracy and the welfare state project it pursued, whether in office or in opposition, in the post-WWII-era.

Such a vision for the future doesn’t automatically develop out of memories of a better past. It needs to be actively created. This requires political interventions that allow people to see their past in a way that opens prospects for a better future. Without such prospects, ‘backward-looking memories’ can lead to a demoralizing and demobilizing yearning to restore an irredeemable past. The frustrated recognition of the impossibility to restore the past may then open the door to right-wing praise of the glorious past of the chosen people. Falling for such praise inevitably leads to frustration as this ideological cover stands in stark contrast to the politics that new right formations pursue. Rather than offering alternatives to an unloved present, these formations aim at the further radicalization of neoliberalism. Avoiding a vicious cycle of right wing policies thriving on backward-looking memories, further radicalization of neoliberalism and frustration fueled by the outcomes of such radicalization requires not only the opening of future prospects for a better world. It also requires an understanding why better conditions that existed in the past ceased to exist. In this particular case, this means an understanding of social democracy and the welfare state project it pursued, whether in office or in opposition, in the post-WWII-era.

Limits to Social Democracy

Blueprints for an organized capitalism in which the spoils of rising productivity would be shared between labour and capital were floating around socialist circles for quite some time. They only came to fruition during the Cold War. The overarching goal of containing Soviet Communism prompted capitalists’ willingness to strike a deal with social democracy. On the basis of unprecedented and, after the experiences of the Great Depression, unexpected prosperity such a deal could be reached without cutting into company profits. Social democratic theoreticians attributed the prosperity to the virtues of Keynesian demand management that stabilized the accumulation process and therefore reduced the risk of large-scale investments. This Keynesian story is true but incomplete. It misses the role played by the unequal exchange between cheap resource imports from and relatively more expensive industrial exports to the South. And it misses the role played by unpaid household labour and the super-exploitation of groups of workers, often immigrants, who were excluded from the deal between capital and organized labour. The convergence of struggles of these excluded groups, militancy of unionized workers and anti-imperialist movements in the South represented a formidable threat to profit rates from the late-1960s onwards. In the mid-1970s this threat coincided with a crisis of overproduction, on its part induced by a long boom of investment in production capacity and the rise of new industrial economies in Asia.

At that point, capitalists decided to turn from welfare state compromise to neoliberal class struggle from above. This included a global restructuring of production and distribution processes that ultimately destroyed the social basis for the various but largely unconnected movements that had challenged capitalist rule in previous years. During the Keynesian era, capitalists had more or less grudgingly accepted social reform as a means to contain the real or just assumed threat of communism. When that acceptance turned into a threat to profits and capitalist rule in its own right, they built a global economy in which the quest for social reform pushes capitalism to the verge of revolution. At this time, social movements – remnants of old workers’ movements and the new social movements of the 1970s but also movements dating back to the alter-globalization movement of the 1990s and more recent anti-austerity movements – are far from posing a revolutionary threat. At best, they slow the continuation of neoliberal restructuring down and articulate alternatives to the new right. Experiences made in these struggles might contribute to the remaking of working class politics that could effectively challenge capitalist power in the future. •

This article will be published in Dutch in the June-July of Aktief, the review of the Belgian Masereel Fonds.