We all suffer from the absence of working class politics. We are smothered in the business-oriented, neoliberal ‘consensus’ instructing us to reconcile ourselves to ‘the new reality’ – rollbacks in social welfare and universal publicly funded programs; huge tax cuts to business and the rich, driving up public debt and enriching finance capitalism; an end to secure employment and guaranteed benefits; surrendering our dreams of home ownership unless we are prepared to accept a lifetime of debt enslavement; a future

of uncertainty and endless personal struggle to sustain ourselves and our children. Flippant commentators now tell us the proletariat has been replaced by ‘the precariat’, and this will define the future of this new capitalism.

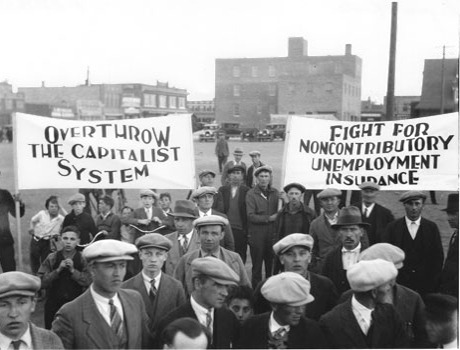

Where is the alternative systemic vision: a world beyond capitalism with economic security and a guaranteed future, a world we can embrace and ask our children to embrace, a world we can realize through our democratic collective action? In the past working class politics, and the early mass agrarian movement, played key roles in painting such a vision in technicolour. But they did more. They organized and fought to transform the ugly present of exploitation and insecurity into a future of hope. And many of them endured savage repression as the price for defying capitalism and agitating for a better future, a socialist future. Some paid with their lives.

Where is the alternative systemic vision: a world beyond capitalism with economic security and a guaranteed future, a world we can embrace and ask our children to embrace, a world we can realize through our democratic collective action? In the past working class politics, and the early mass agrarian movement, played key roles in painting such a vision in technicolour. But they did more. They organized and fought to transform the ugly present of exploitation and insecurity into a future of hope. And many of them endured savage repression as the price for defying capitalism and agitating for a better future, a socialist future. Some paid with their lives.

Victories in Struggle

We all benefit from their remarkable achievements, even in today’s neoliberal world. We still enjoy the right to organize unions and to strike (thanks to Premier Brad Wall’s excesses, now a constitutionally protected right), universal publicly funded healthcare (under serious siege); universal public K to 12 education (we failed to extend it to university and childcare); for most, a standard of living and a sense of social and economic security that is still, despite neoliberalism’s best efforts, the envy of much of the rest of the world. All these and more are deeply rooted in the victories achieved over a century of struggle. And the struggles were led by, and found their popular support in, the working class – and here in Saskatchewan, among progressive middle class farmers. We tend to take today’s entitlements for granted, and too often shrug it off as neoliberalism’s bought and paid for political parties, cheered

on by the tame capitalist mass media, systematically dismantle these gains piece by piece, program by program, in a slow relentless counter-attack which began in the 1970s.

Saskatchewan’s working class surrendered its independent political voice when its organized sector, small socialist parties and trade unions, joined the organized farmers to found the Farmer Labour Party/Co-operative Commonwealth Federation (FLP/CCF) in 1932. In exchange the working class, through its unions, obtained significant, often decisive, influence on the program of the party and then, after the 1944 victory, the policies of the CCF government. From 1944 to 1964 organized labour sent full slates of delegates to conventions to obtain pro-working class policies. The Minister of Labour was a prominent trade unionist (the Minister of Agriculture, a progressive farm leader).

Although the working class never got everything it asked for, it got a great deal, as did its political partners, the organized farmers, the other pillar of this unlikely socialist coalition. It was the working class and the progressive farmers who brought in public ownership on

a large scale, generous labour standards (farm labour excluded in deference to their farmer partners), progressive labour laws including quick and painless certification of unions, the beginnings of a system of universal social and health security, an aggressively progressive tax system – and finally, medicare. The Tommy Douglas government (1944-1961), having already abandoned public ownership of natural resources in 1948 to the consternation of the working class and progressive farmers, would never have campaigned on medicare in the 1960 election if the working class and the organized farmers, through their delegations at conventions, had not pushed the issue relentlessly, year after year. The truth is, Saskatchewan’s organized working class and organized farmers were the real “Fathers of Medicare,” not T. C. Douglas and Woodrow Lloyd.

The working class and its leaders had to re-learn independent political action during the years of defeat of the CCF/NDP under the harsh anti-labour regimes of W. Ross Thatcher (1964-71) and Grant Devine (1982-91). It was a difficult learning curve each time, since organized labour had gotten into the habit of relying on its political influence in the CCF/NDP to make new gains while protecting those already won. It was not until the second term of each hostile government that the trade unions, having worked to create coalitions with other activist groups, carried out aggressive extra-parliamentary campaigns, and tough strike actions, helping to lay the foundations for the NDP’s re-election in 1971 and 1991.

Neoliberal Blitzkrieg

After 1971, Allan Blakeney, the first leader without activist roots in the movements which built the CCF, loyally delivered to the working class and its trade unions, repairing much of the damage done by Thatcher and pushing forward on a spirited social democratic program. Representatives of the working class were initially welcomed back into the cabinet and government. A serious breach with labour occurred in 1975 just months after the June re-election of the NDP when Blakeney supported Trudeau’s October, 1975 wage control program, in retrospect the first salvo of the coming neoliberal blitzkrieg. On October 14, 1976 28,000 Saskatchewan workers participated in an illegal walkout to support the Canadian Labour Congress’ call for a one-day national general strike to protest wage controls. From then on relations between the Blakeney government and organized labour soured, as his government faced a series of bitter strikes in the public sector. Nevertheless, the working class and its unions continued to support the NDP based on its progressive direction in other policy areas.

A very different scenario emerged in 1991. When Roy Romanow won the election, he abandoned social democracy, embraced the business lobby and neoliberalism, and turned his back on the working class and organized labour. This was a game changer as the leaders of the organized working class confronted a new and uncomfortable political reality – the NDP could no longer be counted on to defend the working class and to enhance its entitlements. This became crystal clear when Romanow refused to amend labour laws in a pro-working class direction, and peremptorily legislated striking power workers back to work in 1998 and striking nurses in 1999. The nurses defied the law with broad public support and won their illegal strike, wounding the credibility of the Romanow government, setting the stage for his near defeat in 1999. The working class was no longer an active partner in an NDP government, though its votes were counted on as electoral captives of the party. The working class vote had nowhere else to go, though rates of working class abstention during elections began a sharp upward trajectory.

When Brad Wall’s Saskatchewan Party swept to power in 2007 the working class and its trade unions were already defeated, unwilling and unprepared to fight back. Wall commenced an assault on labour, rewriting all labour laws in a pro-capitalist direction and effectively banning strikes in the public sector. Wall essentially dared unions to go on strike. Wall’s two subsequent victories with massive majorities, against the ineffective and moribund NDP, confirmed the working class faced a powerful and popular class enemy committed to its repression. But for the Supreme Court victory declaring Wall’s effort to ban strikes in the public sector unconstitutional and the right to strike was protected under the Charter, organized labour won nothing. What good is a constitutionally protected right to strike when unions are so beaten into the ground they are unwilling to strike? The working class disappeared as an effective actor in the province’s politics and public life. Unions rolled over, agreeing to lengthy collective agreements peppered with concessions and low wage increases during boom times in the provincial economy. The organized working class remains in retreat, a trend worsening with the collapse of the economy.

When Brad Wall’s Saskatchewan Party swept to power in 2007 the working class and its trade unions were already defeated, unwilling and unprepared to fight back. Wall commenced an assault on labour, rewriting all labour laws in a pro-capitalist direction and effectively banning strikes in the public sector. Wall essentially dared unions to go on strike. Wall’s two subsequent victories with massive majorities, against the ineffective and moribund NDP, confirmed the working class faced a powerful and popular class enemy committed to its repression. But for the Supreme Court victory declaring Wall’s effort to ban strikes in the public sector unconstitutional and the right to strike was protected under the Charter, organized labour won nothing. What good is a constitutionally protected right to strike when unions are so beaten into the ground they are unwilling to strike? The working class disappeared as an effective actor in the province’s politics and public life. Unions rolled over, agreeing to lengthy collective agreements peppered with concessions and low wage increases during boom times in the provincial economy. The organized working class remains in retreat, a trend worsening with the collapse of the economy.

As the recognized leader of Saskatchewan’s working class and its trade unions, the Saskatchewan Federation of Labour (SFL) faces formidable tasks: re-awakening the working class to begin resisting; building coalitions with progressive forces around a new vision of society; persuading progressive forces that a better future can be won through organization and struggle. It has been done before, and it can be done again. The SFL, with 100,000 members, is a sleeping giant. But it can only go as far as its 37 affiliates allow. If awakened, and mandated by its affiliates, it can begin a process leading to new progressive coalitions to organize and agitate around inspiring future possibilities. Perhaps we can start modestly: campaigns for creating green jobs in a green economy; for not just defending medicare from cuts, but expanding it into a truly universal, cradle-to-grave public healthcare system; for expanding our public education system to include university and daycare; for fighting inequality by proposing a fair and aggressively progressive tax system; for demanding more revenue from our natural resources. Such campaigns, as people are engaged, will inevitably lead to the contemplation of a new socialist society and economy – a new inspirational vision. Who knows where that discussion might lead, given the dreadful state of our politics?

Most importantly, forget the NDP. Its time has passed. It can perhaps serve as the ‘least of evils’ parking lot for our votes until something better can be built. •