Harper is gone, but (as a friend only quarter-jokingly said) we got the second worst outcome sold as the best, so now what? That’s the 10 second version of this post. I want to throw out a few questions or, better yet, problems that I think the Canadian Left will have to face together over the next few years. There are no easy answers here.

In 2015, the Liberals once again showed that they are masters at campaigning to the left. But as we now wait for them to show how equally apt they are at governing to the right, it’s clear that it won’t simply do to say ‘told you so!’ in four years time. It is not by accident that the Liberals are Canada’s ‘natural governing party,’ for if anything, they know how to govern. They are experts at balancing competing interests or, more accurately, giving the semblance of balancing interests all the while closely aligned with the interests of the elite, and the upper middle class.

In 2015, the Liberals once again showed that they are masters at campaigning to the left. But as we now wait for them to show how equally apt they are at governing to the right, it’s clear that it won’t simply do to say ‘told you so!’ in four years time. It is not by accident that the Liberals are Canada’s ‘natural governing party,’ for if anything, they know how to govern. They are experts at balancing competing interests or, more accurately, giving the semblance of balancing interests all the while closely aligned with the interests of the elite, and the upper middle class.

Still, we have to recognize that things will be different and that this affects where people are and how they relate to politics. On the one hand, the Liberals do open up some space on the left by making symbolic gestures here and there; at the same time, they close off this space by drawing the limits of respectable progressive politics. They don’t fill the void left by a weak left as do the Conservatives with their exclusionary, pocketbook politics aimed at the working class. In fact, they speak to a broader cross-class progressive segment of the population in a way that can be disorienting.

Low-Hanging Fruit

This new government has already shown itself very adept at picking off the low-hanging fruit of progressive demands. Take the long-form census. It is a relief to those (me included!) who care about the worthy goal of increasing social knowledge. This is an opening: new data could add a stamp of officialdom to the growing inequalities and stagnation we see around us. Yet more fine-grained social data is also an extremely useful tool to further undermining the universal welfare state with ever finer benefits targeting and micro-politics.

Or take climate change. Recently, Canada joined the ‘ambitious’ group at the COP21 summit in Paris, advocating for a maximum 1.5C rise in global temperatures. This goal is laudable; it is what many left green groups have demanded. But it also looks to be largely rhetorical. Given no enforcement mechanisms over national targets, it is also telling that the Liberals took Stephen Harper’s old targets to the summit – targets that are highly incompatible with the ‘ambitious’ goal.

The question is how to turn the openings, both the genuine ones and those that are largely rhetorical, into entry-points for the left into public discussion and public life. It is all the more difficult to do so without fostering any illusions about the Liberals but also without creating a purely critical mode of engagement that closes us off those whose politics (rightly!) include joy in the Harper’s and the right’s defeat.

Then there are those who are alienated from the political process, concentrated among the more exploited and discriminated segments of the population. How do we organize, talk to and listen to them?

Pushing Against the Boundaries

Or another way to phrase this first set of questions: how do we push against the boundaries set by technocracy? Technocracy is the natural terrain of the Liberals and also of parts of the professionalized and bureaucratized social democracy. Their guide is a battle of ideas: if we could only convince elites that our ideas are better, they would listen. The left should be at the other pole. Left politics is not technocratic; it cannot be the rule of experts from scales small to large. This is just rephrasing the old (and difficult) saw of taking people where they are, while developing together through common action, thought and struggle.

If that’s a first, broad, political communications theme, then the second big theme must be the political economic. We need to see how the Liberal victory fits into the search for a way out of stagnation not just in Canada but around the globe. Again, the deficit in the given situation was a positive campaign promise and used adroitly against the NDP. The form it will take is key, however. It looks to be roughly limited to public infrastructure spending amidst an effective investment strike by private capital. Investment looks to be even more pitiful now that oil prices look to stay low for some time and oil projects were a big investment driver.

Sure, Canada sorely needs new infrastructure. The question is what infrastructure we will get and whether there will be any expansion of public services. Building what capital won’t and what it needs while leaving unchallenged its right to an ever-greater share of the social surplus is an elite project. And ultimately balancing the budget on the backs of the poor and working classes while reducing the ability of the state to create universal services appears to be part of that.

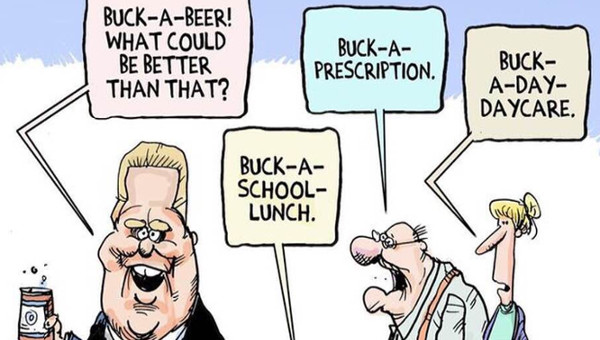

Not harbouring illusions means recognizing that the Liberal program will most likely be one that further entrenches the state at the service of capital. There will be some spending in light of the new low-interest, low-investment, underemployment conditions, but it will be mixed with further curtaining of the welfare state. Consumption support will happen only via targeted cash transfers without any attendant universal programs of state purchasing (for instance, child benefits versus childcare). Here, too, though there are some disorienting elements such as the initial commitment to limit public-private partnerships (P3s) – an unexpected positive sign to follow and use as a pressure point.

The bigger question asks where are the weak points to intervene with an eye to today’s political economy. Where are the social struggles that can have outsize influence, especially given that capital is constantly looking for the crutch of the state, but a state reformed in its interests? Where are the places to build alternative thought and action that opposes the elite project without a purely negative colouring? And who are the groups, constituted or unconstituted, that can put up these challenges?

Here’s the final, maybe most challenging question: that of organization. If there are important pressure points that the Liberal victory exposes but if the old left formations (unions, social democratic parties, social movements) are either weak and fragmented or consigned to the status quo, where and how do we rebuild? This – the question of on-the-ground strategy that goes beyond ‘just act!’ – might be the most important. And it has to be answered quickly.

The Electoral Sphere

No inventory of questions would be complete without a look at local, provincial and federal politics. While narrow electoralism cannot be the focus of our organizing, it is valuable to ask whether and how electoral campaigns can be incorporated.

The NDP is mired in myopia after their loss. The size of the loss might be seen as an opportunity, but more likely it means that it is easier for the party to fall back into its cocoon of insider machine politics. It would be great if we could have our Bernie Sanders or our Jeremy Corbyn bringing the language and the politics of democratic socialism into the media, into debate and into people’s homes and onto their phones. A sober look at the NDP suggests that, for a complex of reasons, this will not happen anytime soon. Perhaps this makes the task clearer.

On a completely different scale, there is the model of Solidarity Halifax, which is already producing a local electoral campaign, seemingly in the general mould of Kshama Sawant’s campaign, though much more organizationally than individually-driven. Is this something to work toward as part of a broader left response to the current political climate? Do we work toward building local electoral experiments as a means of building capacity? How to combine this with an extra-electoral shared political home that goes beyond the limitations of the old organizations?