At this moment, it seems that Harper’s Conservatives are losing ground, headed for possible defeat or minority status, if recent polls are to be believed. If these trends continue, it might represent a long-awaited respite from years of unrelenting and hard-edge neoliberal offensive in all walks of Canadian life. It provides a potential opening to begin to undo the foundations of the dramatic right-wing shift that so many on the left and centre of Canadian politics, predicted would never happen here.

For socialists and the larger working class, as well, Harper’s likely defeat would present opportunities: to organize collective resistance in and around the labour movement; to raise and deepen demands for renewed social programs, minimum wage increases, infrastructure and new challenges to the current social and economic regime. But a number of obstacles will remain – from the inability and unwillingness of the electoral opposition to present real alternatives (both the NDP and Liberals); the relative weakness (and lack of radicalism) of labour and other working-class based social movements; the embedded strength of material and ideological gains of neoliberalism, and the lack of any organized class-based socialist political movement or party with any resonance.

For socialists and the larger working class, as well, Harper’s likely defeat would present opportunities: to organize collective resistance in and around the labour movement; to raise and deepen demands for renewed social programs, minimum wage increases, infrastructure and new challenges to the current social and economic regime. But a number of obstacles will remain – from the inability and unwillingness of the electoral opposition to present real alternatives (both the NDP and Liberals); the relative weakness (and lack of radicalism) of labour and other working-class based social movements; the embedded strength of material and ideological gains of neoliberalism, and the lack of any organized class-based socialist political movement or party with any resonance.

Living Under Harper

The damage done by Harper and his colleagues is all around us, and his defeat would be welcome.

The economy is mired in slow growth, if not recession, with an increasing percentage of precarious jobs, terrible living conditions for key components of Canadian working people, in particular, indigenous communities, and the poor in urban centres, small towns and agrarian areas. We remain reliant on the extraction and export of raw materials, especially fossil fuels, and most damaging, the huge investments in the tar sands.

Ten years of Harper have resulted in a reduction in the size and capacity of the elements of the state that provide limits to private market dependence (healthcare, public pensions, etc…). It has reduced taxes,

as well as expanded capital mobility and carried out an open and steady attack on the right to strike and unions.

It has moved the country to a renewed cold-war foreign policy. Much of it is geared toward winning political support from key conservative communities and constituencies inside Canada with ties to conservative or neocolonial forces that the Tories support (right-wing Ukrainians and conservative elements in Jewish communities, etc…).

There has been a deepening institutionalization of a more profound neoliberalism in state institutions and throughout the economy of Harper (C-51, entrenched Oil and Gas; TPP and EU; judiciary appointments; CBC;

healthcare, etc…), and the further cheapening of democratic norms (proroguing parliament to avoid debates, limiting voting rights,

ceding key decisions to private capital and the requirements of neoliberal orthodoxy, new repressive forms of incarceration, using tax authorities to persecute critics etc…).

Defeating Harper is a key goal for socialists and for the interests of the labour movement and the larger working class. It would be extremely naive to ignore the danger of another Harper majority, or minority, in the sense that extended mandates from Reagan/Bush and Thatcher helped to institutionalize key political and structural changes, (not to mention the transformed cultural environments of the U.S. and Britain).

The longer they remain in power, the more difficult and protracted is the struggle to undo the damage and move forward.

Polls say that the general population is tired of Harper, and the Duffy scandal, intransigence over the Syrian refugee problem and cynical references to “old stock Canadians,” reinforces the general cynicism about the Conservative government, in many spaces, except in the hard-core Conservative base. But Harper is relying on the long campaign, the attack ads against Liberal Leader Justin Trudeau and NDP Leader Thomas Mulcair, (perhaps an ‘October surprise’ agreement on the Trans-Pacific Partnership free trade deal) and appeals to narrow interests and wedge issues geared toward upper-middle class and working class suburbanites around the Ontario

suburban centres, conservative elements within immigrant communities, financial elites satisfied with Tory policies and rural and oil and

gas- affiliated and financial elites and economic interests.

Where are the Electoral Alternatives?

There aren’t any real clear political choices that will fundamentally challenge and undo the deep destruction of Harper and those who came before him.

The Liberals were the architects of much of the foundations that Harper built on: free

trade agreements (NAFTA, others); changes to the structure of the state and cuts to the social wage, deregulation, enhanced capital

mobility, etc… They collaborated with Harper (except for a brief interlude) in deepening military integration with the U.S. anti-terror

war, bringing in repressive laws (voting for C-51) – and reliance on fossil fuel dependency. Trudeau Jr. has no plan to change course,

but will soften it around the edges, and with his cynical pitch to the ‘middle class’, parading Paul Martin as a champion of deficit

spending and promoting infrastructure spending. While sorely needed and appearing to outflank Mulcair on the ‘left’, it is difficult

to see this actually being applied – much the same as Chretien’s famous Red Book, that was trashed by Martin in his “hell or high water” 1995 budget cuts. His foreign policy shows no real deviation from that of Harper, either.

There is also a Green Party, led by the redoubtable Elizabeth May, with a small representation in Parliament. Its platform is better, in some respects than the NDP and Liberals, it has no pretentions to act as the U.S. Green Party (which run as an alternative to the neoliberal consensus of the two main parties), and has little chance of doing more than possibly earning some seats and intervening on some issues. There are also small more radical parties, but they have little resonance in this election.

Mulcair and the NDP present a series of dilemmas and contradictions for socialists and the larger working class. They could be the first federal NDP government in Canadian history – whether ruling independently, in minority or in agreement with or in coalition with the Liberals. In the larger political history of the

country, this is significant – it would mark the first time that a social democratic party was elected on that level, although the nature of social democracy in this neoliberal era undermines that significance.

There are modest reasons to recommend voting the NDP, in a basic comparison of the programs of the three parties [NDP’s plan]. They promise spending increases

(such as the childcare program, OAS, etc); restoring Post Office home delivery, reducing the pension age; rescinding C-51; a minimum wage increase, infrastructure spending, withdrawing subsidies to oil and gas industries other reforms. All of these are important and some could open up space for further struggles at the base, such as the minimum wage and Post Office.

One would also expect a break from the paranoid attacks on civil servants and fact-based analytical capacity of the state and some restoration of capacities, like restoring the long form census. Also, there would be better and more respectful relations with first nations and links

with labour. As well, there likely would be efforts to lesson direct participation in aggressive international projects (like ISIS bombing).

But there is nothing fundamentally different in Mulcair’s larger approach in key areas:

- On the environment, a commitment to reviews of large projects is not the same as moving away from fossil fuel energy and extraction, and its centrality as an economic generator. The tar sands project remains, along with commitments to refine bitumen, rather than use what we have to transit toward renewables, and leave the rest in the ground.

- A slavish commitment to ‘balanced budgets’. The Liberals have dragged out Paul Martin to argue that you would need to borrow in order to get through another major recession or downturn – once again, swiped on the left.

- Refusal to increase personal taxes and a measly 2 per cent increase in corporate taxes.

- Many of the proposed reforms wouldn’t take hold for years and require political agreements with the provinces.

- Commitment to free trade and no efforts to challenge capital mobility, no move toward controlling financial capital, or private capital at all. The entire spending package is based partially on modest corporate tax increases, or, more to the point, successful economic performance of private capital investment.

- The rhetorical attacks on Harper’s destruction of the manufacturing sector are underpinned by a relatively ineffective series of subsidies to private capital and a rather inexplicable commitment to small business. Not a hint of economic planning, and gearing a renewed manufacturing effort, toward the needs of a different, economic model.

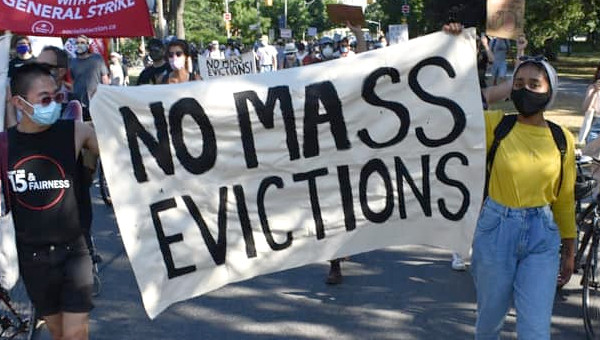

- Their commitment to infrastructure spending is not enough to rebuild a robust public transportation system to serve as a key component of a sustainable urban/suburban development plan (and might be less robust than the Liberal promises). There is no commitment to provide funding for the operational needs of public transit systems. Similarly with the lack of necessary resources to build affordable, public and co-operative housing for working class people in large cities or smaller towns. We await plans to dramatically improve conditions on first nation homelands, or eliminate poverty across this country.

- Support for NATO and Israel, and no effort to develop a left approach to foreign policy, geared toward helping lessen international tension, weaken neoliberal capital and its projects, or facilitating the development of peoples and nations in the global south. We get sort of ‘Harper Lite’, but without the worst international interventions.

- A lot of this is pandering to what they call ‘the middle class’, in order to gain ‘credibility’ in order to get elected. Sounds more like old fashioned opportunism. This clearly doesn’t build confidence of the left and the working class that they would do anything different when (or if) they get elected and challenge the business elite’s efforts to pressure them to move even further toward the right.

- No commitment to consider democratizing the state or sponsoring structural reforms, such as nationalizing the banks or energy resources.

- Life for working class people could see some improvements, but the fundamental transformation of working class life that characterizes capitalism across the world in this neoliberal age: crappy, insecure jobs; ongoing climate change; dramatic reductions on social programs; lack of any real democratic control over the development of our economic lives; ongoing threats of violence and instability in the international arena, buttressed by a dramatically unequal world….The NDP will not contribute one iota to addressing any of this.

- And, if the NDP is so fearful of challenging the basic presupposition of neoliberal obsession with balanced budget, concerned about pissing off financial markets and non-committed voters, why would they respond any differently to similar pressures from business and the right when in office (capital strikes/flight)?

What Should Socialists, the Union Movement

and Working Class Do?

It is clear that no fundamental change will happen as a result of this election. There are no political parties promising a challenge to capitalism,

neoliberalism, austerity, or present a working-class oriented strategy with important structural reforms with any real alternative vision, certainly not the NDP.

Getting rid of Harper is necessary, but it doesn’t make sense to call for supporting the Liberals, as their time in office reflects an approach, at least on economic issues, similar to the Conservatives, as we have seen in the Chretien/Martin era, and would expect from a Trudeau led government. Their current positioning around deficit spending for infrastructure investment is curiously to the ‘left’ of the NDP, with the latter’s obsessive calls to balance the budget. This could theoretically give the Liberals an opportunity to present themselves as the ‘real’ alternative to Harper, and thus don the mantle as the anti-Harper champion, leaving the NDP in the dust. This is unlikely, but possible.

The NDP offers modest alternatives that would not change all that much, but possibly provide some short-term relief for sections of the working class and provide some promises that can legitimate key worker concerns. But progress in each of these areas requires important battles being waged by the labour movement and social movements from below. Currently, there are few signs of mass movements on any of these fronts.

The relationships that the NDP have with the labour movement are somewhat of a wildcard. It can bring some modest gains and a reduction of attacks, or accommodation to the compromises with capital that are sure to come with an NDP government.

Unions are divided in their relationship with the NDP, and this reflects a recognition of the party’s weakness, the confusion within working class organizations about how to orient themselves in this era and a recognition that the NDP is just as confused, as well as the party’s unwillingness and inability to consistently represent working class interests. In many ways, the NDP actually disorganizes the working class, by offering a political vision that relies on the economic and political leadership of private capital, and seeks to reinforce a ‘middle class’ identity, and the separation and weakness of the different components of the working class.

In fact, it’s hard to know what the party stands for – other than getting elected. It is so paranoid at the framing of the Conservatives and so committed to winning over the more conservative swing voters – that it claims that it will never run a deficit (or undo the odious ‘balanced budget’ law), and everyone knows that it is impossible and clearly won’t be done if they get elected. The idea that they will have any guiding set of principles that reflect the interests of the working class is long gone, and most working people know it. This feeds the cynicism about politics, and hardly inspires any movement for change.

Unions themselves tend to have limited, narrow and sectoral approaches to politics and key policies, looking to protect the short term interests of their members, rather than a broader class outlook (see UNIFOR’s self-serving policies on auto subsidies, tar sands and pipelines). In this era of growing precarity and divisions within the working class, it reinforces a notion of unions as being privileged, and, within the unionized private sector, a sense of desperate hope to strengthen the condition of the employers in their respective sectors.

The NDP is hardly part of any challenge to this set of limitations, and instead, feeds it. The relations that key unions have with the NDP often reflect brokerage politics – ways of getting support for their pet policies in exchange for support, rather than acting as voice for the working class. And, the policy approaches of the NDP tend to reflect the more moderate and corporatist policies of individual unions, reflecting the limits of the current union movement which is sorely in need of transformation.

Then, of course, there are the potential spaces where the union movement could unite to pressure a new government and organize support where there is pressure from capital to back off some of the more progressive policies (childcare, modest tax increases, pensions, minimum wage, Medicare spending).

There are also key nodes and relations with left individuals in the NDP caucus and in their policy and administrative entourage, and these could help push forward important initiatives. But they are limited and tenuous.

There is little of the sizzle, excitement and critical depth that follow the new campaigns of Labour Party Leader Jeremy Corbyn in the UK and candidate for Democratic Party nomination Bernie Sanders in the United States. These campaigns push the boundaries of current forms of social democracy (while remaining within the paradigm), and appeal to the disgust and frustrations of working class people with the utter lack of representation and advocacy for their interests in the face of ongoing and steady declines in living standards and the loss of hope. The NDP will not play that role.

All in all, it would make sense for socialists to vote for the NDP, simply as the lesser of evils, and in most ridings, see them as the most likely to defeat Conservatives. Working for them and getting involved in their campaigns seem less exciting and offers very little in return. The entire strategy of strategic voting is hardly compelling: given the long campaign, the unreliability of the Liberals and the unpredictability of outcomes. There is little proof that it has ever really made a difference on a larger scale. But given the sorry state of the NDP central campaign message, socialists would be better off organizing around key issues than NDP candidates, all the while voting for the NDP.

On the other hand, there is a difference between the hard-edged neoliberal approach of Harper and the Trudeau Liberals. In instances where the NDP has no chance to challenge the Tories a vote for a Liberal that can win – or a Green that can win, where they have the best chance – would make sense. There are also situations where young, left activists are running for the NDP, or independent parties. Building in the long run might be best served by supporting them. This is not the same as endorsing ‘strategic voting’ as a strategy – but argues for a certain tactical flexibility, given the rather unique electoral moment.

And, in the event that no party has a majority, we should argue in favour of an NDP-Liberal alliance, based on a platform that rejects the essential tenets of Harper’ Conservatives. We should have no illusions about how progressive this would be – distasteful in many ways – but it might be essential to bring down Harper and open up a new era of Canadian politics.

Beyond Electoral Calculation

Socialists inside the labour movement and social movements would be more effective if we argued for key class-oriented policies – demanding that the NDP respond (although getting unions and movements to endorse them would also be a challenge). These might include such demands as closing the tar sands and transitioning away from fossil fuels dependence; dramatically increasing the CPP; raising taxes on the wealthy and restoring the GST cut; taking steps to end capital mobility; massive and regular spending on infrastructure for public transit and housing across the country; investing in the caring economic sectors (especially Medicare – as UNIFOR is currently doing) and controlling the power of finance.

An important step would be demanding that the NDP and all of the political parties endorse and commit to applying the policies which stem from the recently-issued Leap Manifesto, which raises a program for transitioning to a clean energy economy, many of the elements of which are quite radical and critical for any progressive move forward. Although right now, it is limited to a kind of celebrity-based statement (rather than an organizing centre) and doesn’t really propose an approach that goes beyond capitalism, it promotes many critical reforms and dramatic changes to forms of political governance, challenges to free trade, the environment and the rights and powers of first nations.

In this era, social democratic parties remain completely dependent on the competitive success of private capital in order to fund their rather anemic set of social program spending demands, and in Canada, the latter is closely tied to resource extraction and export, opening up the economy to foreign investment, enhanced capital mobility and the promise of access to investment opportunities in foreign markets. The conditions for competitive success are extremely disadvantageous for the working class in this era, and efforts to look back to the golden age of the post-war years point to a dead end. Social democratic parties in every country (and social democrats in the U.S.) have accepted their dependence on the basic strategic plans of their respective capitalist classes, and it has transformed the meaning of social democracy.

Socialists need to do education on the limits and realities that make it impossible for the NDP to become an instrument for the kind of social transformation we need – in the short run, with important reforms – or in the longer term, with a challenge to the system.

A possible defeat of Harper will not automatically undo the embedded neoliberal changes he and his predecessors have brought about, even if there is a general desire across the country for some kind of progressive change. Jeffrey Simpson, the generally conservative columnist in the Globe and Mail noted in a September 11th column, that even with a Conservative defeat, Harper has “won important battles in the shaping of public opinion,” notably on the opposition to taxes and support for repressive criminal justice policies.

Whether the Liberals or NDP (or a coalition of the two) get to form governments after October 19th, socialists and progressive activists within the labour movement and in and around social movements, would need to wage the battle against the consensus that the Conservatives have built around their vision of Canada and social life, as well as the key policies that underpin them, even in the face of the waffling and likely back-sliding of a new government.

It isn’t as if we know how to do this (we haven’t been all that successful so far), but we have to learn.

Wherever we are active, we have to build an understanding of common working class interests and of the capitalist system in this neoliberal era. Inside unions, in workplaces, in larger labour bodies, in communities and in community-based movements around public housing, poverty, social justice, the environment, anti-oppression, public transit, healthcare, social programs, etc, across the country socialists and our allies need to push for the deepening and widening of reforms, and links across the working class. We need to pressure any new government to live up to its promises, and show their limits – and call to push beyond them.

As well, whatever the outcome of the election, we have to move beyond acceptance of social democracy as the face of the ‘left’ in Canada. We have to contribute to the eventual creation of a socialist political presence, in the larger working class, and eventually as a participant and reference point in the electoral and larger political system. •