The Coalition of the Radical Left, or Syriza, is favoured to win parliamentary elections on January 25, giving it a strong chance to form a new government that could confront the catastrophic austerity agenda that has plunged Greece into severe economic and social crisis. Here, Lee Sustar (from the Socialist Worker, where this article first appeared) answers questions about the rise of Syriza and what a victory for it on January 25 would mean.

Why is so much attention focused on the Greek elections?

It may seem surprising that an election in a small country of less than 12 million people could create high anxiety in government ministries in Berlin and Paris and at the European Union (EU) headquarters in Brussels. But as the Russian revolutionary Lenin once wrote, the chain of imperialism is only as strong as its weakest link, and Greece certainly fits that description.

The crisis in Greece emerged in the aftermath of the financial panic of October 2008, when the government was no longer able to make payments on its outstanding debts. The European Commission – the executive arm of the EU – stepped in, along with the European Central Bank (ECB) and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Known collectively as the “Troika,” they agreed to bail out the Greek financial system, but only if the country slashed government employment and salaries, made deep cuts in social spending, and privatized government services. At the same time, regressive taxes that hit workers hardest were actually increased. The revenues going to the government immediately flowed out of the country to repay foreign debt.

Austere Bailout

The austerity-mongers insisted that these methods would work by lowering labour costs in Greece, which would, they said, revive investment in the Greek economy. It didn’t work. The first bailout had to be followed by a second. A third bailout was under discussion when the conservative government of Antonis Samaras unraveled in December. The money was needed simply to enable the Greek government to keep its debt payments flowing. Greece’s economy plunged in a way unseen since the Great Depression, even as the amount of debt continued to increase relative to the size of the economy, reaching 175 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2013 and remaining at 168 per cent today.

In 2012, the specter of Greece’s potential exit from the euro – the common currency shared by 19 countries – created waves of financial panic when Syriza nearly won national elections.

Greece’s economy is fairly small by European standards, with a gross domestic product (GDP) of $242-billion in 2013, compared to $2.1-trillion for Italy or $1.4-trillion for Spain, countries also mired in low growth. A run on Greek banks or a default on Greece’s debt could have had a domino effect on other European banks and lead investors to dump Italian or Spanish government bonds, creating huge problems for those countries.

More recently, the Greek economy has seen a small recovery from its catastrophic collapse, achieving what’s known as a “primary surplus” – economists’ jargon for a government budget surplus prior to the repayment of debt. European banks and their regulators at the European Central Bank now claim that they’re far healthier and thus no longer at risk of a possible “Grexit” from the euro. But the bankers can’t be trusted. This is the same bunch who told the world that everything was sound just before the financial crash of 2008. Given the interconnectedness of international finance, there’s no way to know just how banks would be affected by Syriza’s demand to renegotiate the debt.

There’s another big worry for EU bureaucrats and European corporate bosses: The possibility that Greece could set a precedent for other countries by encouraging further left-wing protest against austerity policies that have seen governments across the EU slash budgets and push the costs of the economic crisis onto working people.

More than six years into the economic crisis, most European economies are stagnating. The political fallout has hit establishment parties of the center left and center right – for example, with the National Front making huge electoral gains amid dissatisfaction with the Socialist Party government of François Hollande. Far right and nationalist groups in other countries have also gained in recent elections by scapegoating immigrants in general, and Muslims in particular.

In Spain, by contrast, the left-wing Podemos party, barely one year old, emerged as the most popular party in that country as the result of popular anger against the conservative government of Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy. A Syriza victory would boost Podemos’ prospects and revive the left across the continent.

As the major economic power in the EU, the German capitalist class and its supporters claim that Greece brought the crisis on itself by lying about the weakness of its economy and failing to live “within its means.” Is this true?

The Greek crisis is the extreme form of a crisis at the heart of the European Union – and, within it, the German capitalist class’s attempt to drive the economic organization of the EU.

The European common currency, the euro, was launched in 1999. German capitalists favoured the move, since it consolidated the continent as an export market for German business and rationalized a fragmentary financial system anchored by the biggest European banks, along with the newly created European Central Bank. As a currency, the euro was weaker than Germany’s former currency, the deutschmark, would have been on its own. This made German exports cheaper to the rest of the world outside the EU. The problem was that the ECB lacks anything like the powers of the U.S. Federal Reserve Bank. While the Fed can basically print money to cover U.S. government debts, the ECB can’t do this – and German officials would be against it if it could.

But if the ECB lacks power, the central banks of the individual EU governments have even less. Previously, a country with big debts to pay would slash interest rates and devalue its currency to make its economy more competitive on the world market. Greece – like other euro countries – lacks that power under the terms of its agreement to participate in the eurozone.

Instead, austerity was supposed to achieve a kind of “internal devaluation” – a drastic cut in living standards that would rekindle economic growth, with lower costs of production attracting new investment.

Just how bad is the social and economic crisis in Greece today?

We know the horror stories of social collapse caused by wars and military invasions in countries like Iraq, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Syria. But Greece has endured an almost unimaginable amount of privation without any such armed conflict.

Although the Greek economy returned to growth for the first time in six years in 2014, the economy remains 30 per cent smaller than it was six years ago. In human terms, that translates to millions of lives shattered – and a whole generation of young people deprived of any prospect of a stable and secure life.

According to researchers for the Greek parliament, some 2.5 million people (in a total population of 11 million, remember) live under the poverty line, with another 3.8 million at risk for doing so. Some 26.6 per cent of people are jobless – and for those aged 15 to 24, the figure is 52 per cent. Wages have fallen by 5 per cent every year since 2009.

Poverty and unemployment are only part of the suffering of the Greek working-class. According to researchers from the British medical journal The Lancet, some 47 per cent of Greeks say they could not obtain medically necessary treatment. Public education has been savaged, too, with a 33 per cent cut in education spending between 2009 and 2013 and a further 14 per cent cut scheduled by 2016. Thousands of teachers have lost their jobs, and class sizes have exploded.

During recent winters, a large number of people died of carbon monoxide poisoning due to the use of wood stoves – since heating has become unaffordable for millions. Countless numbers of people struggle to make do with a barter system, offering whatever skills or services they can in exchange for other services – or merely for food. There has been nothing like this in the economically advanced world since the Great Depression of the 1930s.

How did Syriza succeed in moving from the left margins of politics to being poised to be the leading party of Greece?

Syriza is an expression of the mass sentiment against austerity that has shown itself in wave after wave of popular struggles since the crash of ’08. These are movements that were rooted in previous traditions of popular resistance. To understand why, it’s useful to look at Greece’s political history of intense political polarization in the 20th century.

In the 1930s, the military dictatorship of Ioannis Metaxas served as a prelude to a Nazi occupation (Metaxas still has his admirers). In the aftermath of the Second World War, the country exploded into a civil war that pitted the Greek hard right against the left – with the Communist Party (KKE, according to its initials in Greek) playing the leading role in the resistance.

In 1967, another military dictatorship subjected a new generation of leftists and working-class militants to murderous repression. But a popular protest movement and a wave of strikes in 1974 overthrew the dictatorship and opened the door for the election of the center-left party PASOK in 1981. PASOK maintained a firm basis in the trade unions even as it moderated popular demands in the name of stabilizing Greek capitalists. For their part, Greek bosses, in the aftermath of the dictatorship, were compelled to make significant concessions to the working-class, including a reduction in the workweek from 48 to 40 hours and the introduction of paid vacations.

Unlike most Western European countries, the Greek left and organized labour remained vigorous and influential after the collapse of the USSR in 1991 disoriented Communist Parties internationally, and industrial restructuring and pro-market neoliberal policies hammered union strength. Nevertheless, the Greek left remained fragmented. PASOK, which alternated in government with the conservative New Democracy party, retained the support of a large section of the unions. For its part, the KKE remained an old-school Stalinist formation, disdaining any united front with others on the left and abstaining from any struggles that it did not control. (The exception was the KKE’s formation of a brief government in coalition with New Democracy in the 1990s in the name of opposing corruption in PASOK).

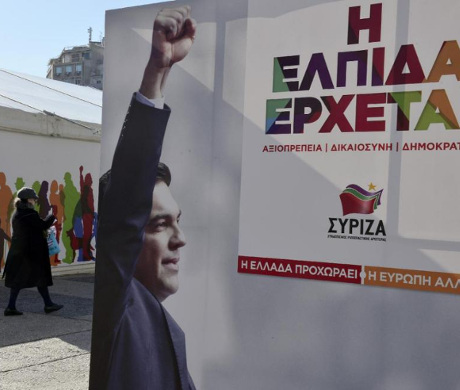

Over the past decade, however, new currents on the Greek left emerged – some from a split in the KKE, others drawn to activism in the global justice movement of the early 2000s, and still others from struggles involving labour unions and immigrant rights. Syriza (the acronym stands for Coalition of the Radical Left) became the vehicle for these currents, which include the ex-KKE activists in the Synaspismos group, always the largest component of Syriza, along with disaffected PASOK members and Trotskyists such as the Internationalist Workers Left (DEA). Syriza’s best-known leader Alexis Tsiprsas was trained in the KKE’s youth group before rejecting the party’s sectarianism and organizing with its “eurocommunist” split.

For several years after its formation in 2004, Syriza remained relatively small. But the explosive strikes and protests since 2008 opened up a new audience for its radical, anti-austerity program. The dominant PASOK and New Democracy parties had both pushed the bailout deal with the IMF-ECB-EU troika. Since 2012, the two parties have been governing in coalition to keep Syriza out of office. This is the context in which working people involved in the dramatic general strikes and popular mobilizations a few years ago have now thrown their weight behind Syriza, turning it into an electoral voice of the popular resistance.

In May 2014, Syriza won the most votes in elections for European parliament. It was an electoral expression of years of struggle, including 16 general strikes and a diverse series of mass social struggles. As Sotiris Martalis, a member of DEA and a figure on the left wing of Syriza, said following those election results:

“The political crisis and the rise of the left are not just a product of the economic crisis, but also the result of two years of hard-fought workers’ and social struggles. It is also a result of certain political choices. This can explain why working people chose Syriza as a ‘tool’ to express themselves, and not the Democratic Left [a split from PASOK], the Communist Party or ANTARSYA.”

The neo-Nazi party Golden Dawn suffered a series of arrests after its thugs murdered a popular musician. Does the far right remain a threat in Greece?

The rise of Syriza has its counterpart on the right in the rise of Golden Dawn, which got 6.9 per cent of the vote and 18 seats in the last parliamentary election. Unlike far right politicians like Marine Le Pen of France’s National Front, Golden Dawn is a straightforward Hitlerite organization, from its swastika-type insignia to its deadly racist attacks on immigrants.

Golden Dawn’s popularity has declined since one of its members murdered rapper Pavlos Fyssas, and the government veered from a tolerance of the neo-Nazis to a crackdown on the organization and the arrest of all of its members of parliament.

But Golden Dawn is likely to get seats in the next parliament and will remain an ominous force, thanks to its well-documented connections to establishment right-wingers and military figures. Right-wing authoritarianism and fascism have deep roots in Greece, and these neo-Nazis will continue to present themselves as an alternative to people driven to desperation in the crisis.

What will happen in Greece if Syriza wins, and what will it mean for the left?

There are significant forces on the Greek left – the KKE and the far-left electoral coalition known as ANTARSYA – which claim that Syriza will seize the first opportunity to collaborate with Greek capital. Panos Garganas, an activist in the Greek Socialist Workers Party (SEK, by its initials in Greek), which is part of ANTARSYA, wrote that Syriza is “appeasing the bankers while appealing to voters.” The KKE is even more direct, accusing Syriza of being “the left reserve force of capitalism.” This is a mistaken and sectarian position. There is no question that the Greek and European capitalist class is hostile to Syriza and the working-class and popular forces that it represents.

The Economist magazine, a mouthpiece for European business, voiced hope that what it saw as a moderation and professionalism among Syriza’s top officials would make it possible for a mild readjustment of Greece’s debt repayment and a limited rollback of austerity. A Syriza victory “need not be a disaster,” the magazine said. “Still, Europe’s establishment is right to worry,” the Economist continued, warning that Syriza’s left would push back at any compromise, and the expiration of the bailout package and looming debt repayments come soon after the election.

Despite the tactful approach outlined by the Economist, employers will use all available means to sabotage a Syriza government from the moment it takes office. The capitalist class controls the capitalist state machine, no matter what government is in office. Syriza will indeed be pressured to compromise on the program that has excited large sections of the Greek capitalist class. To survive – let alone advance its program of reversing austerity – Syriza will have to depend on popular mobilization and working-class struggle.

The activists in the KKE and ANTARSYA could and should play an important role in mobilizing for the defense of Syriza’s program against the inevitable backlash. Syriza’s influential Left Platform – an organized presence within the party, representing a significant section of members and well-known leading figures – is organizing against any retreat from the party’s program. It argues that struggle in the workplace and the streets will be key.

Tsipras has already made it clear that a Syriza program will continue to make payments on the Greek government’s massive debt, even as it tries to negotiate relief. Even so, the party’s program is unmistakably left wing and will lead to a head-on collision with the EU institutions and big business. It involves a ‘haircut’ – a negotiated partial default – for the holders of bonds issued by the Greek government; free electricity for the poorest households in the country; subsidized food and rent; a return to free health care; increased funding for pensions; and a vast jobs creation program. To pay for all this, the government plans to tax the wealthy oligarchs who have long hid their wealth overseas.

“The coalition is demanding things from the ECB and European Union that it simply won’t do (like fund its programs),” wrote Business Insider journalist Mike Bird. “That means that for the first time, there may be an entire EU member state just refusing to go along with European policy, which is a massive challenge for the whole continent.”

There is no close historical precedent in Europe for a Syriza victory – although there are some parallels with the 1970 election of a socialist government led by Salvador Allende in Chile.

But in the years following the Russian Revolution, there was a valuable discussion of the prospects for just such a development in the Communist International – the international alliance of revolutionary organizations formed in the wake of the revolution. This debate centered on whether revolutionary socialists should participate in workers government – that is, a government of radical or revolutionary parties to the left of traditional social democratic parties.

The debates at the Fourth Congress of the Communist International – annotated minutes of the proceedings were recently republished by Haymarket Books – focused on how workers who were not yet prepared to take power by revolutionary means could nevertheless give their electoral support to workers’ parties. Antonis Davanellos, a leading figure in DEA and in Syriza’s Left Platform, discussed the relevance of that debate in today’s Greece:

“The criteria for its program must be bound – mostly or exclusively – to the needs of the working-class and the popular classes, and not to some cross-class vague concepts such as ‘the country’ or the ‘productive reconstruction of the economy.’ The criteria on its alliances must be confined to workers’ parties and organizations, and not extend to broad alliances that sacrifice the clear sociopolitical orientation for the sake of parliamentary efficiency. The criteria on the prospects of a left-wing government must be understood as a transitional step toward socialist rupture, and not as a final destination that will ‘save the country.’”

The key question was what such left-wing parties will do in office to mobilize workers struggles against a hostile state bureaucracy and capitalist class, with strikes, factory occupations, sit-ins at government ministries and the like. Such struggles are essential to fortify revolutionary and working-class organization in what is certain to be a series of high-stakes confrontations with capital.

What can the left in the U.S. and the rest of the world do in solidarity?

A Syriza government will have to contend not only with the Greek bosses, but with the international capitalist class.

As the elections neared, German Chancellor Angela Merkel and other European heads of state were keeping their cards close to their vest. One can expect a mixture of bribery and bullying, in the hopes of driving a wedge into Syriza and demoralizing its electoral base. According to this scenario, New Democracy will wait for a Syriza government to implode and make a triumphant return, with an even harsher austerity program.

That’s why international solidarity with the Greek left and a defense of the Syriza government will be crucial. From public meetings explaining what’s happening to organizing campaigns against governments and bankers to protest the efforts to bleed Greece dry, the left can play an important role.

At a time when mainstream parties worldwide continue to squeeze workers to protect the profits and privileges of a tiny minority, a Syriza victory will give voice to the left-wing alternative that we urgently need. •