The Electoral Collapse of SYRIZA: The Left and the Coming Election

The meteoric rise of SYRIZA in Greece in 2012 and the resounding double victory of 2015 (one in January and the second in September, after the great compromise of July 2015) seems to have ended with the crushing defeat in the May 21 elections. The collapse was emphatic, with all the groups and regions where the Left – PASOK in the past, and SYRIZA in 2015 and 2019 – used to have a decisive advantage lost: Crete, the young (17-25 years-old), and Athens working-class districts. SYRIZA suffered the most from the proportional representation system they introduced in 2016, clearly not anticipating the ever-likely possibility that the conservative party New Democracy and Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis would maintain the lead in government, which they first won in July 2019 with 39.8% of the vote (compared to a marginally higher 40.8% of the vote in this election).

Other far-right parties, like Greek Solution, also did marginally better (their vote share increasing from 3.7% to 4.4%). The Yanis Varoufakis-led MeRA25 proclaimed ‘an incredible tsunami, a conservative front’, as it failed to meet the 3% threshold for winning seats.

Why did SYRIZA do so much more poorly than most polls predicted? How surprising was New Democracy’s victory? Is Greek society as conservative and reactionary as some on the Left claim? What does SYRIZA’s collapse portend for the left in the upcoming election on June 25?

Media and Predictions

There is some irony in the fact that the dominant neoliberal media system constantly reminded the public during the election campaign about SYRIZA’s compromise after the July 2015 referendum despite the fact that SYRIZA pulled the country out of the strict financial controls in 2018. The media domination over the last few years amplified the message and put SYRIZA and its leader, Alexis Tsipras, on the political defensive. However, some of the media wounds were self-inflicted. Against the suggestion of a post-election coalition government that SYRIZA claimed was imminent after the elections, Mitsotakis’ message was unambiguously for a single-party government.

Tsipras and SYRIZA may have underestimated Mitsotakis but so did most polls prior to the election. New Democracy certainly benefited from a strategic takeover of the national security agency and the press. By summer 2021, the Mitsotakis government had accumulated several failures. There was the wiretapping scandal with the malware ‘predator’ that became news during the summer of 2021. Greece had suffered under major fires exacerbated by obvious government negligence. The number of COVID victims kept rising and was only going to get worse the following winter, while inflation was creeping in. After the Tempi rail disaster in central Greece on February 28, 2023, which killed 57 people, the polling difference was down to 4 percentage points, but indications were not auspicious for SYRIZA and its leader Tsipras.

Why, then, did the polls underestimate support for New Democracy? Many have argued that last-minute undecided voters made the difference, but it is likely that the margin was already quite wide during the pandemic. Polling companies have been accused of misleading public opinion with results not representative of the ‘real mood’ of the people. But did they? In the end, they were accused not because they missed the margin between the New Democracy conservatives and SYRIZA (and other left parties) by only a little, but because they missed it by a lot.

It was clear that New Democracy would win, but what explains the vast difference? One could follow the money. During the pandemic and its aftermath monetary easing by the European Central Bank meant availability of more than €50-billion to support certain sectors of the economy, money that the Mitsotakis government continued to disburse even weeks before the elections (most controversially, a payment of €150 to all 18-years old, ostensibly to encourage them to get vaccinated). Despite these opportunities to capitalize on controversies and scandals, SYRIZA appeared more as a protest party than a government in waiting.

600,000 Voters Abstained

No one expected a New Democracy victory of 20 percentage points. SYRIZA approached this election buoyed by the 31.8% share of the vote in the parliamentary elections of 2019; however, the 24% of the European Parliament elections was most likely closer to the mark. If we take this view, then the current 20% is still a relative underperformance but less disastrous. SYRIZA did not manage to convince the electorate (which at 61% participation, was slightly higher than the 58% of the previous elections) that it was a government in waiting because it did not perform convincingly as the main opposition. The expansion of the party membership during last year’s congress was not reflected in an expansion of the electoral base. On the contrary, SYRIZA lost about 600,000 votes, the majority of which did not move to other parties. These voters did not even turn out. What was the ‘missed opportunity’?

SYRIZA lost districts, age groups, and debates where it had traditionally maintained an advantage. The lack of clarity, incoherent messaging, and a gambler’s conviction that with proportional representation SYRIZA could form a government with the rejuvenated PASOK, contrasted with an entirely opposite message. New Democracy promised to rule not after this first election that would have made a coalition government compulsory, but rather after the next election with a different electoral law passed by New Democracy that grants the first party a sliding scale ‘bonus’ of between 20 to 50 seats (out of 300), depending on its share of the popular vote. The missed opportunity of proportional representation was a major miscalculation that SYRIZA failed to disentangle, as no party expressed the intention to form a coalition government.

A Turn to the Right?

Many Greeks on the left are concerned about whether there is a conservative turn that saw parties on the right (including the far right) for the first time getting a higher percentage than parties on the left. Whatever conservative turn there is, it is more complex than that. While this is the first election without the banned Golden Dawn (the Greek Supreme Court also upheld the ban against its successor Hellenes in a decision on May 2, 2023) other far-right parties have emerged to take its place. Greek Solution received 4.45% of the vote, while Victory received 2.9%.

Even though New Democracy’s share of the popular vote didn’t increase much (less than 1%) their policies have certainly shifted right-ward, reflecting a trend among conservative parties across Europe. They ended the University Asylum law in 2019. Their appallingly reactionary approach to migrants (including building a 140 km fence in Evros region) will receive renewed scrutiny on the news that a fishing boat carrying an estimated 750 migrants capsized, with 78 confirmed dead as of June 15. While social austerity is still in place, New Democracy has more than doubled military spending since 2018, to the highest among NATO members (spending 3.54% of GDP, beating the US at 3.46%). Real wages are still 25% lower than 2007, and headline inflation hit 9.3% in 2022, before easing to 6.3% in the first quarter of 2023. Perhaps having lowered expectations is what led to even those who barely make ends meet fearing for the worse and then preparing to vote for the ‘devil you know’.

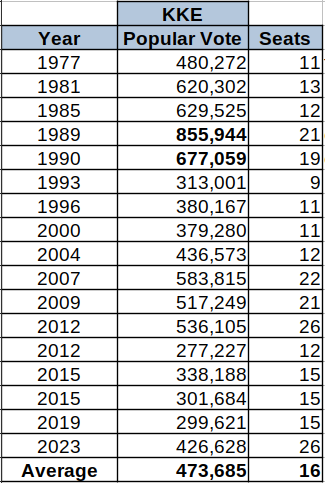

Nonetheless, both PASOK and KKE (the Communist Party of Greece) increased their share of the popular vote (by 3.3% and 2.9% respectively) and seats (by 19 and 11).

Mobilising the Left

This election raises many questions about the relation between left parties and Greek society today. How does one lift morale, mobilize and convince people to vote, and, in fact, to vote for SYRIZA? Tsipras often repeats Ignacio da Silva Lula’s motto: “Better in government a Left that does what they can than a right that does what they want.” Evoking moral arguments is still in the arsenal, but the failure to ‘read’ society has cost SYRIZA dearly. The elation of 2012-15 gave way to the flat period in government of 2015-19, and finally, to their lackluster role in opposition during 2019-23. If they insist on trying to conceal their left-wing identity – as many social democratic parties have done in the face of neoliberal hegemony – in a bid to gain ‘centrist’ votes, disillusionment with SYRIZA among the Greek left will persist, and they will not be seen as a legitimate alternative.

The painful shock of the defeat by 20 percentage points will be difficult to recover from. Since the results, SYRIZA has changed its electoral committee, promised to form a more cohesive team and project a clearer message, now that, interestingly, they don’t have the stress of proportional representation. While he confessed in an interview that he thought about resigning on the night of May 21 elections, Tsipras will have to deal with a succession unless there is a spectacular, and again unpredictable, result in the June 25 elections. At the same time, he assumed responsibility for the defeat, declared the end of the “grief period” four days after the elections, and the campaign is now on. It is, by far, the most difficult battle that SYRIZA and Tsipras have fought, and they are slowly bringing the debate to a focus on their much more convincing program for government that was missed in the pre-election mono-thematic talk about who SYRIZA will govern with.

Any talk of a leadership change that may be brewing is suspended until after the June 25 elections. Whether SYRIZA can remake itself after the election remains to be seen. It will take a new leader, though it is uncertain at the moment who that may be. At the moment, the SYRIZA electoral committee has tried to re-focus political attention to their economic and social programme, which failed to inspire and bring out voters in the May 21 election. With SYRIZA seriously defeated, PASOK as the Centre Left gained about 3%, but remains the distant third party at 11.5%, and both parties combined still received less than New Democracy.

The Communist Party of Greece remains indifferent to government and a few smaller parties are emerging that may challenge New Democracy from the right, with new conservative parties probably exceeding the 3% required to enter parliament. The coming election raises concerns about the state of the left; but it is more concerning that the pre-election campaign has seen New Democracy attacking even the Muslim minority candidates of SYRIZA in north-east Greece, targeting the minority as a whole because their district was the only one where SYRIZA came first, even if this jeopardizes future Greek-Turkish negotiations.

The media propaganda is relentless and has worked mostly by the absence of any critical questions directed at New Democracy candidates and misleading by avoiding the real issues of impoverishment, a neglected healthcare system, and deteriorating working conditions especially in the tourism industry. On the May 21 elections the SYRIZA electoral law gamble failed, their campaign of doom and gloom was not enough for people to vote for them, because people know how bad things are, how much worse they can get, and they need to be inspired. This is probably what SYRIZA and Tsipras lacked the most: the ability to still inspire and instill hope. Whether they can convince us that they have a realistic and socially progressive government plan may go some way to mitigate the damage however irreversible this may be. •