Early this month, the Canadian section of Israel’s quasi-governmental Jewish National Fund (JNF) made a big show of honouring Stephen Harper at its annual “Negev Dinner.” It was the first time a sitting Canadian prime minister served as the gala’s honouree – and a grating reminder of how bad Canadian politics on Palestine have gotten. “Prime Minister Harper awkwardly sang classic rock tunes for an agonizing 20 minutes,” notes[1] Dru Oja Jay, writing for The Media Co-op. Those recoiling at the thought may not be shocked by a further detail provided by the Canadian Jewish News: “Many in the crowd left as Harper was still singing.”[2] Harper’s anti-Palestinian record may be impeccable, but even JNF donors have their limits.

With the Globe and Mail heralding[3] the gala as a “capstone” of Tory friendship with Canada’s Jewish community – won, so the Globe‘s Craig Offman tells us, through reversal of Canada’s “infuriating” diplomatic weakness under the Chrétien Liberals – the spectacle offers a useful reference point for considering the depths to which Canadian politics on Palestine have sunk. In this the Tories’ Israeli flag-waving does indeed stand out. But as Oja Jay observes, it is hardly the whole of the problem. In this article, I look back at some of the historical precursors to this month’s display, and then turn to the cringe-worthy political climate that makes such Tory posturing politically rewarding.

With the Globe and Mail heralding[3] the gala as a “capstone” of Tory friendship with Canada’s Jewish community – won, so the Globe‘s Craig Offman tells us, through reversal of Canada’s “infuriating” diplomatic weakness under the Chrétien Liberals – the spectacle offers a useful reference point for considering the depths to which Canadian politics on Palestine have sunk. In this the Tories’ Israeli flag-waving does indeed stand out. But as Oja Jay observes, it is hardly the whole of the problem. In this article, I look back at some of the historical precursors to this month’s display, and then turn to the cringe-worthy political climate that makes such Tory posturing politically rewarding.

War on the “Region of Darkness”

Harper, as we’ve learned over the past several years, takes positive pride in colonial anachronism. Were any reminder needed, the JNF celebration provided it. And so it was without a hint of irony that the prime minister took to the JNF stage and declared that Israel, the barbarians no doubt at its gates, is nothing less than a “light of freedom and democracy in what is otherwise a region of darkness.”[4]

Throughout the West one often hears echoes of Theodor Herzl’s 19th-century proposal for the role of a Jewish state in Palestine. “We should there form a part of a wall of defence for Europe in Asia, an outpost of civilization against barbarism,” wrote the founder of political Zionism – in 1896.[5] An age of decolonization later, the concept has proved durable, but the language is usually finessed. Harper’s old-school rendition once again betrays his faith in the imperial classics.

There’s every reason to wince at the display, but over several years it’s become familiar. The Harper Tories have, if nothing else, succeeded in developing an approach to the Middle East in which Israeli flag-waving and classic imperial nostalgia neatly dovetail.

Recall July 2006, a critical landmark in the sharpening of Canadian alignment with Israel. This was the summer that Israel’s killing of Palestinians in Gaza spiralled, following the July 12 capture of two Israeli soldiers by Hizbullah, into a massive Israeli invasion of Lebanon that killed more than a thousand Lebanese and threatened an expanded regional war.

Mid-month, Harper travelled to St. Petersburg to take part in the G8 Summit. At the summit itself, the Harper government aligned itself more closely than any other with the encouragement of Israeli attacks then coming from the Bush administration; this was the pattern through the summer.[6] The diplomacy itself was as destructive as it could have been. But for present purposes the speech that Harper delivered on his way to the summit, during a stop-off in London, is just as memorable.

Harper’s talk[7] was hosted by the Canada-UK Chamber of Commerce. It advocated for open-ended international war (“on terror,” of course) without directly discussing either the Palestinians or Harper’s favourite, nuclear-tipped “light in the region of darkness.” His comments nonetheless suggest a worldview into which the destruction of Palestinian society fits all too comfortably.

“I know it’s unfashionable to refer to colonialism in anything other than negative terms,” Harper assured his business audience. But what do the fashions of decolonization matter to a fighting leader of the white Anglosphere? The prime minister thus turned back the clock with outright praise for Britain’s history of imperial “brilliance” and “magnanimity,” to which Canada owes everything. It was the kind of celebration of Canada’s imperial heritage that hadn’t been heard from a Canadian prime minister for decades.

Significantly, the speech quotes heavily from Winston Churchill, possibly Britain’s ranking 20th-century imperialist. For Harper, Churchill’s prized English-speaking peoples must again rally for war: “once more we face, as Churchill put it, ‘gangs of bandits who seek to darken the light of the world.’ . . . And Canada’s new national government is absolutely determined, once again, to stand shoulder to shoulder with our British allies, to stay the course and to win the fight.”

In his embrace of classic imperialism, Harper even managed to invoke, if indirectly, the English arch-racist Karl Pearson. Had Britain ever been seriously forced to grapple with its racism, or Canada with this shared heritage, this would have been a scandal. Instead, it was with full political impunity that Harper quoted Churchill reflecting on “all those massive stepping stones which the people of the British race shaped and forged to the joy, and peace, and glory of mankind.”

Arundhati Roy reminds us that Churchill himself justified supporting the colonization of Palestine in precisely these terms: “I do not agree,” Churchill explained in 1937, “that the dog in a manger has the final right to the manger, even though he may have lain there for a very long time. I do not admit that right. I do not admit, for instance, that a great wrong has been done to the Red Indians of America, or the black people of Australia. I do not admit that a wrong has been done to these people by the fact that a stronger race, a higher grade race, a more worldly-wide race, to put it that way, has come in and taken their place.”[9]

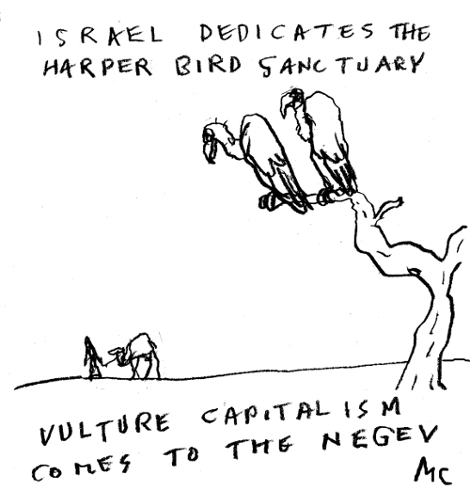

For the likes of Harper, such filth remains a guiding principle, decolonization be damned. Oja Jay’s piece for the Media Co-op notes that the JNF “bird sanctuary” in the Galilee that the JNF named after Harper as part of this month’s celebration – “The Stephen J. Harper Hula Valley Bird Sanctuary Visitor and Education Centre” – occupies land from which Palestinian Bedouin were ethnically cleansed in 1948. Harper can be noted for his callousness, but not for his originality. On Palestine as generally, the prime minister remains true to his pedigree.

Palestine and the British Empire’s “Iron Heel of Ruthlessness”

The JNF’s educational “bird sanctuaries” join a mass of deceptive diplomacy and writing in seeking to erase Palestinians from the history and landscape of Palestine. Such erasure remains a central alibi for Zionist colonization. As the activist intellectual Naseer Aruri observes from a historical angle, “The absurd and indefensible allegation that there were virtually no Arabs in Palestine prior to the Zionist influx seems intended to provide a veneer of legitimacy for Israel’s increasingly violent efforts to make the myth that there is ‘no such thing as a Palestinian’ a chilling reality.”[10]

Harper’s display this month is a reasonable cue to look back at how these politics have played out in Canada. For many decades, a disciplined separation has been maintained between celebration of Canada’s association with Zionist colonization and discussion of the impact that this colonization has had on Palestinians. The historical record is one of the places where this needs to be broken down.

Taking the cue from Harper’s pride in heritage, consider one of the early contributions from Canada to the dispossession of the Palestinians: the pre-1948 purchase of the coastal Palestinian territory of Wadi al-Hawarith.

These were more modest days of Zionist colonization. Not until 1948 was the Zionist movement able to seize Palestinian land directly and by force. (At this point, incidentally, the Canadian Zionist movement contributed weaponry and recruited combatants, aiding in the massive robbery of lands that the JNF then stepped in to help manage.) Earlier, the movement had more limited means.

The range of possible options were identified early on by the Zionist official Menachem Ussishkin: “as the ways of the world go, how does one acquire landed property? By one of the following three methods: by force – that is, by conquest in war, or in other words, by robbing land of its owner; by forceful acquisition, that is, by expropriation via governmental authority; and by purchase with the owner’s consent.”[11] Ultimately, in 1948, the movement applied a combination of the first and second methods: land was directly expropriated by forces that morphed into the Israeli state during the course of the robbery, which Israeli law then ratified. Until then, it relied on a combination of the second and the third methods: legal title to land was by various means “purchased” by the Zionist movement, and state authorities were then enlisted to evict Palestinians from it.

This strategy, like political Zionism as a whole, only really gained momentum thanks to Harper’s “magnanimous” Empire. Britain occupied Palestine during the First World War and committed to ruling the country in line with its famous Balfour Declaration, pledging Imperial support for the “establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people.” Among the things that Canada owes largely to the Empire is its early Zionist history.

While British support for the Zionist movement reverberated globally, its impact in Britain and its settler-colonial “Dominions” was especially straightforward. Here the Zionist leadership could pressure Jews for support as almost a patriotic duty. In Canada, for example, Zionist activity was regularly presented as contributing to the fulfillment of Imperial policy; this goes some way toward explaining the failure of anti-Zionism to ever get a foothold in “respectable” Canadian Jewish circles.

So it was in 1927 when Ussishkin, then president of the JNF, met the leader of interwar Canadian Zionism, Ottawa department store owner Archie Freiman (president of the Zionist Organization of Canada, ZOC). At the time, the JNF was working to transform the meaning of land ownership in Palestine. Ownership of legal title to lands had previously had only a limited effect on the peasants or tenant-cultivators living on and working the land. Sometimes the cultivators might have to provide landlords with a share of the crop, but often ownership was not much more than a formality. For the JNF, in contrast, ownership meant evicting Arabs. Such colonization obviously required funds.

Enter Canadian Zionists. By means including lobbying and bribery, Zionist officials produced an opportunity to buy the land around Wadi al-Hawarith, previously owned by distant absentee landlords.[12] Ussishkin then enlisted Freiman to get the necessary funds through the ZOC. Together, Ussishkin and Freiman extracted a commitment from Canadian Zionists to raise more than a million dollars for the project over the coming years.[13] In Palestine, the JNF made the deal.

The case of Wadi al-Hawarith is significant in that its obvious impact on Palestine has been meticulously written out of Canadian history. The territory was home to a community of an estimated 1,000-1,200 Palestinian Bedouin, who resisted the first attempt to evict them (in 1929) with sticks and stones. Over the coming years, as British authorities dismissed the community as a “pocket of primitive Semi-negroid Beduin,” in the words of Britain’s assistant commissioner for the Nablus district, support for their anti-eviction fight spread.[14]

Parallel to Canadian fundraising to pay off the purchase, the struggle against the eviction order it had triggered continued for years. By 1933, it developed to the point where a general strike in Nablus was organized in solidarity with the cultivators. On the anniversary of the Balfour Declaration late that year, a demonstration from Wadi al-Hawarith was only prevented from linking up with protests in Tulkarem by deployment of British police units supported by low-flying RAF planes.[15]

Canada’s Zionist Organization, meanwhile, continued to press Canadian Jews to support its political priority during the early years of the Great Depression: fundraising for this displacement. At the ZOC’s 1930 convention, Freiman took continued pride in the insistence that by supporting Zionism, his organization was “at the same time fostering the interests of our Empire.”[16] With these politics, official government blessing wasn’t hard to come by. In early 1934, as Canadian Zionists worked to pay off their pledge to Ussishkin, Canada’s then prime minister RB Bennett joined Freiman in a joint radio appeal for donations. “Scriptural prophecy is being fulfilled,” Bennett declared. “The restoration of Zion has begun.’[17]

This was, bear in mind, the same Bennett who was meanwhile busy trying to crush any popular challenges to his Depression-era austerity agenda under “an iron heel of ruthlessness” (his words).[18] Then, as now, patriotic Zionists found themselves in fitting company.

Brazen Racists & Spineless Liberals

In carrying on the traditions of a Churchill or a Bennett, the Harper Tories have distinguished themselves over the past several years for their brazen colonial pride. This is something of a crisis. But while the government deserves to be singled out, it’s clearly being enabled by the country’s broader political atmosphere.

The burying of the historical record, for its part, results largely from liberal Canadian racism. Gerald Tulchinsky, one of the most skilled historians of Canadian Jewish (including labour) history, provides a prominent example. In what is probably the leading study of Canadian Jewish history, published by University of Toronto Press in 2008, Tulchinsky casually dodges the Wadi al-Hawarith struggle with another classic: he declares the purchased land to have simply been “a large tract of uninhabited sand and swamp.”[19] After all, people don’t even need to be dismissed as “semi-Negroid Beduin” if they didn’t exist.

Even very recent history loses most of its substance once passed through mainstream Canadian filters. Consider, to take one final example, the familiar political background on Canadian Middle East politics that the Globe and Mail provides in its coverage of the JNF gala.

The Globe piece, Craig Offman’s “Jewish community finds a friend in Stephen Harper” (Nov 30), was the main mainstream article discussing Canadian politics on Palestine in light of the JNF festivities. Offman, in a sense quite correctly, mentions the events of summer 2006. This period is by common agreement an important reference point in thinking through Canadian support for Israel.

Offman’s summary is the standard one: “In 2006, leader-to-be Michael Ignatieff talked about war crimes for Israel’s attack on Lebanon, a remark for which he later apologized.” Offman goes on to explain that Ignatieff’s criticism of Israel, like the Chrétien Liberals’ “infuriating” weakness in supporting Israel at the UN, was grounds for defection to the Tory camp. The fact that Ignatieff’s “war crimes” comment is the only piece of this 2006 story that has survived, to be regurgitated by reporters at every opportunity, reveals more about Canadian political culture than about the substance of the history.

Briefly, these were the actual details. In summer 2006, as Harper channelled Churchill and Israel expanded its aerial killings from Gaza to Lebanon, the federal Liberals were in the midst of a leadership race. Of all the Liberal candidates, Ignatieff waited longest to call for a ceasefire. By the time he finally did, international outrage was building over Israel’s widely publicized aerial killing of Lebanese civilians, including at least 28 people, 16 of them children, in a single July 30 airstrike at Qana.[20]

This outspoken advocate for the Iraq war[21] didn’t want to give the wrong impression. Ignatieff explained to the press that he hadn’t called for a ceasefire earlier because “it was very important for Israel to send Hezbollah a very clear message”; but the Israeli assault had accomplished what it could, had reached a point of “diminishing returns,” and should now be concluded.[22] When a Toronto Star reporter asked whether his mind had been changed by the killings at Qana, Ignatieff once again displayed his high tolerance for collateral damage: “This is the kind of dirty war you’re in when you have to do this and I’m not losing sleep about that.”[23]

Many felt that Ignatieff had been too outspoken in his callousness, that his language had been too crass. The comment, it was decided, had been a leadership-race “gaffe.” As the Edmonton Journal and a few others reported, “Liberal leadership front-runner Michael Ignatieff frankly admits he goofed when he said he was ‘not losing sleep’ over civilian deaths in Lebanon.”[24] The story then rapidly faded from coverage.

Or from the Anglo Canadian mainstream, anyway. By autumn 2006, Ignatieff was apparently concerned that his comments had left a more lasting impression in Quebec, where anti-war sentiment tends to be stronger. And so he tried to backpeddle. Speaking to the French-language program Tout le monde en parle, he explained: “I was a professor of human rights, and I am also a professor of the laws of war, and what happened in Qana was a war crime, and I should have said that. That’s clear.”[25]

“… the Canadian press corps has done its best to help show that there is no place in mainstream Canada for such unequivocal criticism of aerial child-killing. By now the rules are well established.”

The backlash to Ignatieff’s critical blip (the “war crimes” mention) has been as sustained as attention to his indifference-to-the-massacre “gaffe” was brief. Through a standard narrative in which the “war crimes” misstep provides the main lesson from 2006 inter-party competition, the Canadian press corps has done its best to help show that there is no place in mainstream Canada for such unequivocal criticism of aerial child-killing. By now the rules are well established. Dismissing the Middle East as a “region of darkness” is fine. Getting too detailed about one’s indifference to a particular massacre of its people may rate as a “gaffe.” Suggesting that it is criminal to kill Arab civilians, in contrast, makes for a scandal of record.

Conclusion

In The Question of Palestine (1979), Edward Said wrote that Western celebration of Zionism and Israel, and the refusal, from right to left, to look at the implications for Palestinians, was “one of the most frightening cultural episodes of the century.”[26] Much has changed into the current century, but the problem hasn’t gone away.

In Canada, what political progress on these issues had been made has been partly reversed by the imperial regression that the Harper Tories have driven. Unfortunately, the general atmosphere in the press and through the political culture has made these reverses all too easy.

On the other hand, real gains have been made. As recently as the 2003 invasion of Iraq, it was possible for significant anti-war currents to actively distance themselves from engagement with the Palestine question and Israel’s regional role; these topics could be set aside as divisive or too contentious without undermining an organization’s basic credibility. Finally, it seems, those days are solidly behind us.

This shift has come amidst a relative lull of anti-war activity, which has perhaps limited its immediate effects. But its impact is likely to endure. There is now widespread agreement on the anti-war left that the Palestine question needs to factor centrally into efforts to challenge Canada’s destructive international role. In this setting, and as this month’s spectacle reminds us, active discussion is required to figure out how to most productively challenge the grim consensus that has taken hold across the Canadian mainstream. •