On September 11, millions of Chileans commemorate 40 years since the coup d’état in which the Palace of La Moneda in Santiago was attacked by warplanes and President Salvador Allende died fighting the conspirators. This event marked years of state terrorism and bloodshed in our country and the fortieth anniversary of the assault has been a political and emotional recollection for our friends and comrades from around the world.

It has been revealed and recognized internationally that Chilean military personnel were trained by the USA School of Americas to terrorize political dissidents, leftists and progressive organizations. Likewise, terrorist gangs were financed by the CIA to kidnap, torture, kill and disappear political prisoners. The origin of the Coup can be found in the strong alliance between the Chilean ruling elites, the armed forces and the United States. Each time workers, shanty town dwellers, peasants, the indigenous Mapuche and students attempted to promote change and reform in Chile, the political right and its armed wing, the police and the Armed Forces, brutally repressed them. The Armed Forces have historically acted in defense of the privileged classes in power, attacking those who struggled for their rights. It has never functioned in reverse.

Democracy in Chile has been the reflection of an institutional political arrangement that favours the dominant classes and foreign capital – an issue still relevant in the present – to exploit natural resources and labour without restrictions. The coup d’état dealt with the political and class struggle that shook the country in an international context defined by the Cold War. For the United States another Latin American country shaking free of its control was unthinkable.

The Role of Imperialism

Forty years later we continue to mourn the people who disappeared, were tortured to death and killed in Chile. A day of mourning for the victims of the terrorist attacks is a symbolic homage to human losses. Too many lives taken. Too much pain to endure. Who is responsible for these fatalities? The Chilean ruling elites or the U.S. and its aggressive imperialistic foreign policies? Maybe both!

As we continue to witness today, the U.S. government prioritizes an aggressive global agenda almost everywhere in the world. In the letter and spirit of the ‘manifest destiny’ approach to power, not much has changed. State or imperial terrorism is still at large claiming victims and causing destruction. Seriously, how much and up to what extent have imperial policies really changed when hegemony can be replaced by dominance or invasion? Does the U.S. have more or fewer friends than 40 years ago? And what does it mean to the oppressed people around the world, beyond the core capitalist countries, when they have to confront the same domestic and foreign SOBs when they demand sovereignty and independence?

In Latin America, the U.S. has installed hundreds of military bases for training local militaries and/or the police. With the end of the cold war and without the so called communist threat, what kind of terrorism does the U.S. need to fight in this region? The indigenous people, the newer left, or perhaps the proponents of twenty-first century socialism?

A Tide of Change is Sweeping Latin America

Twenty-first century socialism has been articulated in movements that have both renewed politics and the ways it is practiced. It is different than the anti-capitalist, socialist-oriented movements of the 1960s and 1970s. As social mobilization develops and challenges the established power, it also dares to break open the sacred territories of formal power, participating in legal and institutional spaces, as well as in practice to transform constitutions and integrate sectors usually excluded from public and institutional life.

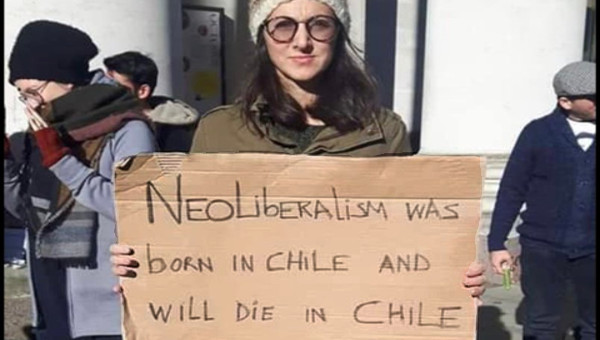

What has developed within some sectors and regions of Latin America is a new way of understanding and approaching politics. This proposal implies a new culture of participation that questions the right and left and, in a relentless manner, capitalism in all of its forms. Political categories are being redefined in a region subjugated by a neoliberal ideology that has become a civilizational paradigm, transforming even the political culture of contemporary societies.

Practical convergences of reformist struggles with revolutionary and democratic content are visible, making possible the implementation of significant changes in the Andean countries of the continent. Resistance to the neoliberal business and political designs is due to the strength and creativity of broad social movements promoting an agenda that represents the needs and interests of the people, thereby creating a favourable context for new struggle and transformation.

In Chile neoliberal politics were imposed under a military-business dictatorship and until very recently the climate did not appear favourable for challenging the current right-wing government led by Pinochet’s cherubs who represent the legacy of the dictatorship, even after more than twenty years of transition to democracy. This is a fearful democracy that had changed the administration of power and made signals toward the protection of human rights, while it continued to repress and criminalize social movements and indigenous communities. It also promotes the criminalization of dissidence by creating new laws to take it to court.

Toward Re-Imagining Chile

While the state protects anti-democratic institutional bodies that benefit the de-facto and authoritarian power, it simultaneously employs legal mechanisms to expand benefits and capital accumulation. We are talking about a state conceived of and designed to meet the needs of neoliberalism. The cost, however, is paid by the environment, common goods and working men and women: the fallacy of the successful businessmen is based on the dynamic of double exploitation of the environment and labour.

The powerful students’ struggle of the past three years is questioning the roots of neoliberalism in the educational system as exemplified in 2011, when students began demanding free education and an end to the debt they were forced to assume in order to study. They also confronted the state and the government concerning profits in educational establishments because in neoliberal Chile businesses that provide services, especially in the areas of finance and retail, are characterized as “industry,” and education is no exception. It has become like any factory, mining, chemical, wood or industrial complex. In other words, education is another sector of economic activity developed to expand the frontiers and strengthen the expansion of capital through onerous fees and high interest rates on educational loans, transforming it into a type of double surplus value extraction.

The student movement has persuaded diverse sectors of society to join the students in their demands; they made it clear that they were the children of workers and therefore part of the social fabric of the nation. As such, their problems extended to all parts of society as they did not consider themselves a sector encapsulated by its own imperatives. Nonetheless, the students emphasized their autonomy from political parties, government coalitions and business interests. Moreover, the majority of student federations called for a transformation of society, including the political constitution that impedes the democratic process in matters that directly affect people’s lives.

At present, more than ever, social movements across Chile – from workers of all sectors to students and peasants – are requesting the end of the market in the strategic sector of the economy and the removal of the neoliberal approach in the implementation of social programs: no more market in health, education, housing, and pension plans; no more profits on the state funding of social services.

It seems that forty years after the coup d’état the people finally want to recover their losses and are asking for more state in the economy and social programs, as well as the re-nationalization of common goods ranging from mining to forestry. Beginning on September 11 1973, workers, women and men in general, began to lose the right to organize and to strike, the right to collective bargaining and witnessed the privatization of their pension funds. Overcoming neoliberalism is now in the works.

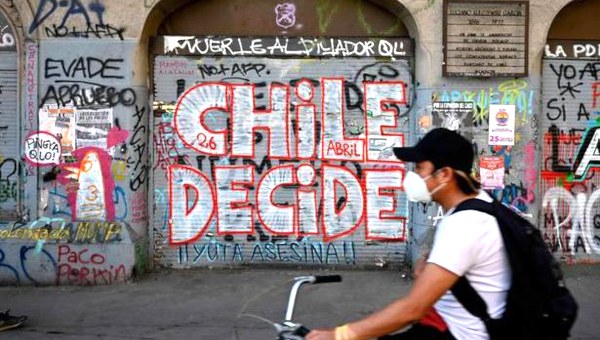

Nowadays we want it all back and more. The debate about a new constitution and the enactment of a constituent assembly is back on the agenda, as is reorganizing the economy and a progressive new tax system. Communities in northern and southern Chile want their regions to have more rights through a decentralized government. The Mapuche-indigenous nation want their land back and reparation for historic losses.

In these days, hundreds of events commemorate the overthrow of Salvador Allende’s government and his death as well as the collapse of a democratic system. Human rights organizations and social movements want all perpetrators of abuses, as well as the collaborators of the dictatorial regime, to pay with jail or social scorn for their crimes. Moreover, many right wing politicians, including the current president, are acknowledging their indifference toward human rights abuses. The Supreme Court has stated the same. Most likely, all of these will in some way influence the presidential and parliamentary elections of November 17 in which the right wing candidates will score major losses.

Today, forty years later, it seems that in the context of the commemorations, the mourning and grieving for the fallen is coupled with the revival of their dreams, our dreams in fact. •