Metrolinx, the Greater Toronto Area’s regional transit authority, has released a short list of revenue tools that they will consider using to help pay for new public transit in the Greater Toronto Hamilton Area. Projects like the Eglinton, Scarborough, Sheppard and Finch light rapid transit lines (LRTs) will need $2-billion a year from sources other than existing government revenue. Options that made it to their short list were: development charges, employee payroll tax, gas tax, high occupancy toll lanes, highway tolls, land value capture, parking space levy, property tax, sales tax, transit fare increase and vehicle kilometres travelled.

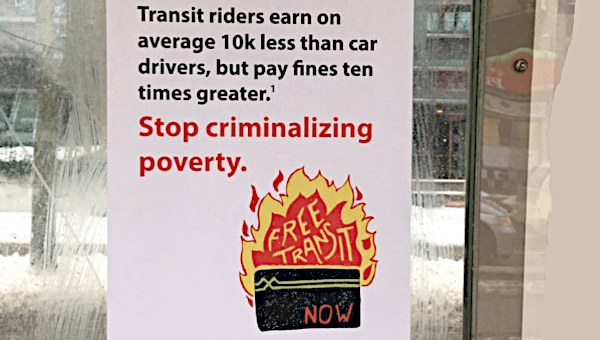

It is almost unbelievable that transit fare increases are still an option. Paying more for transit at the fare box actually discourages transit use by punishing those who can least afford to pay and it doesn’t even generate very much revenue ($45-million). Employee payroll taxes target working-class people through regressive taxation, and property taxes are also highly regressive.

It is almost unbelievable that transit fare increases are still an option. Paying more for transit at the fare box actually discourages transit use by punishing those who can least afford to pay and it doesn’t even generate very much revenue ($45-million). Employee payroll taxes target working-class people through regressive taxation, and property taxes are also highly regressive.

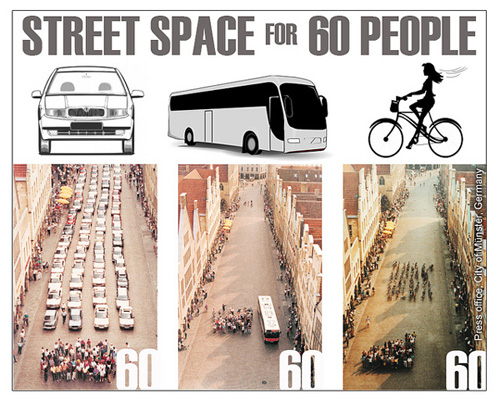

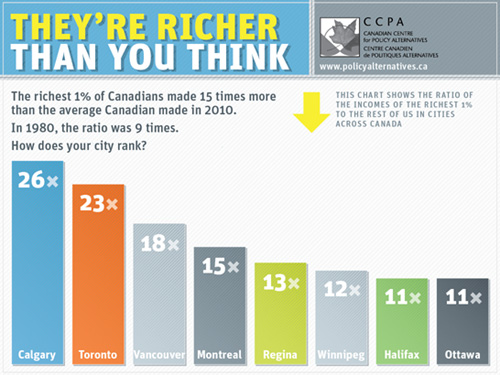

With Toronto second only to Calgary in income inequality, it is crucial that public transit be affordable and accessible to transit users and low income residents across the city. Congestion, smog, stress, long commute times, increased respiratory illness and fare increases, are the result of decades of underinvestment and downloading by provincial and federal governments. They must play a much bigger role in funding existing public transit operations. We need more frequent service and more connectivity between neighbourhoods now. Even with new Light Rail Transit (LRTs), it will still take four transfers to go from Morningside to the Beaches along Kingston Road, and that’s not convenient enough to get people out of their cars.

National Transit Strategy?

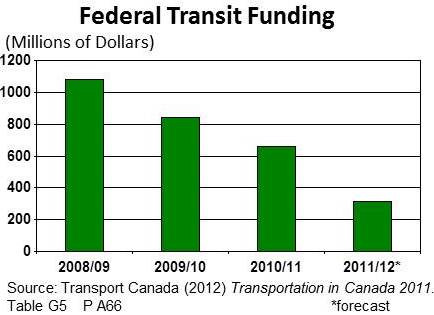

Canada is the only G8 country without a National Transit Strategy. There is no federal money specifically for urban transit. In 2007, when the province first announced plans to expand transit infrastructure, they expected the federal government would contribute $6.3-billion toward the $18-billion price tag. To date, they have only received $300-million. The recent 2013 federal budget reveals a stubborn refusal to address the urgent need for public transit in Canada’s cities. With a cut of $1-billion to federal transfers that could go toward public transit for 2014-15, the Harper government has failed to make public transit a priority.

From the early 1980s the TTC has had to cover at least 68 per cent of the operating costs through fares (the highest fare box ratio in North America) while the provincial subsidy has steadily dropped from around 16 per cent down to a mere 6 per cent in gas tax funding.

Too often TTC Commissioners choose to raise fares to meet the funding shortfall left by downloading. Perhaps they find it easier than holding the provincial, federal or even their own municipal government, accountable. Last year, $22-million was generated from overcrowding due to service cuts, as part of a larger right-wing assault on a host of city services and municipal worker wages and benefits. This money could have been used to avoid another five cent fare increase in 2013. Instead it was funnelled back into City coffers. The majority on City Council fail to recognize the importance of adequately funding this “essential service.” With ridership increasing every year, we should be expanding. Instead we abandon the “Ridership Growth Strategy” and punish transit users with fare increases and service cuts, ignoring the fact that many can no longer afford to use the TTC.

If more service and lower fares in Toronto’s outer areas are needed now, what will happen when new LRTs are up and running? How will the TTC meet this new demand unless higher levels of government provide a stable, adequate subsidy? If the province agreed to properly fund operations, they could use a gas tax, highway tolls, high occupancy toll lanes or a parking space levy to encourage residents to leave the car at home and switch to public transit. This revenue could then be used to offset subsidy costs.

Should we be surprised that corporate and personal income tax on the wealthy, did not make it onto Metrolinx’s short list? Not if this is a government that thinks lowering corporate taxes while 255,000 manufacturing jobs disappear in Ontario is a good idea. Since 2004, the rate has gone from 14 per cent down to 10 per cent. Originally intended to facilitate economic investment, it has had little effect. Instead Canadian corporations have accumulated almost $600-billion which they refuse to put toward anything but bigger bonuses for their CEOs.

According to Joseph Stiglitz, Nobel Prize-winning former chief economist of the World Bank, a three per cent tax increase on higher income Canadians would generate $2-billion whereas the same tax increase on incomes under $30,000 would only generate $154-million. With such a high return, why do we avoid taxing the wealthy and corporations? Does it make sense for them not to have to make a contribution when they will reap most of the benefits from higher productivity that new transit service will bring?

Even a sales tax in combination with fare reductions, free transit for seniors, social assistance recipients, the unemployed or during extreme weather alerts, would significantly increase public revenue ($1.6B) without reducing accessibility.

Transportation for the Community

It is also apparent that many of the revenue tools necessary to pay for major new capital investments involved in The Big Move, are similar to those needed to pay for the maintenance, operation and improvement of the public transit system in the city of Toronto. Any plan to expand the system regionally, must take into account the needs of the TTC and the people that rely on it. The vast sums needed to pay for all of this must come from sources which rely on progressive forms of taxation, higher levels of government – as mobility and urban infrastructure are key elements of social justice and public health – as well as instruments which reduce the use of private vehicles and fossil fuels.

So far, the discussion about public transit expansion and how to pay for it, has been dominated by business concerns around traffic congestion, commuting times and lost productivity, with little regard for basic issues of mobility. The purposes of public transit go beyond getting to and from jobs (themselves structured around the needs of private capital). Transit provides for the needs of everyday living, shopping, social interaction and the way our communities look. If it is to replace the use of private cars as much as possible, we must also consider the needs of everyday transit riders or those disqualified from accessing transit, due to low income or mobility issues. If we truly care about the future of Toronto, they should be our main concern. We don’t charge user fees for public health care, schools, libraries and highways so let’s stop punishing people who improve our air quality by choosing to take the bus. Let’s make sure chronic underfunding from higher levels of government and rising inequality are addressed, before we turn to the fare box, or punishing workers earning low wages. •

Background on Revenue Tools for Public Transit Expansion in the GTA

Introduction

This position paper is a response to roundtable discussions conducted by Metrolinx on revenue tools for the twenty two new public transit projects contained in The Big Move as well as the similarly focussed City of Toronto Feeling Congested public consultation meetings.

The implementation of all twenty two projects in The Big Move will cost $34-billion. The Province has already dedicated $16-billion toward several of these projects including four new LRTs, the Pearson/Union Air Rail Link and the Presto fare card system. The remaining $18-billion, must come from other sources of revenue. At The Big Move Roundtable Conversation held in Toronto on February 9th, 2013, we were told we would need to raise $2-billion a year to cover this amount.

Before considering additional revenue tools, it is important to reflect on the political, socio-economic, and environmental conditions affecting public transit use in Toronto.

Toronto’s Inequality Crisis

Where Women Count: The Women’s Equality Report Card Project – 2010

Data collected from a series of public workshops, conducted by Toronto Women’s City Alliance showed the TTC was crucial for many women and women with children, but high fares often meant choosing not to use transit. Although the majority of transit users in Toronto are women (65 per cent) those travelling with children or with mobility issues do not find it accessible.

The Three Cities Report – 2010

Research by University of Toronto professors J. David Hulchanski, The Three Cities within Toronto Income Polarization Among Toronto’s Neighbourhoods, 1970 – 2005 and Deborah Cowen, Toronto’s Inner Suburbs Investing in Social Infrastructure in Scarborough provide an overview of the stark new reality of suburbs in Toronto. No longer a haven for the middle class, residents of neighbourhoods like Kingston/Galloway (over 50 per cent of immigrant and visible minorities) have seen their income decrease by more than 40 per cent below the average income of $40,704, while residents close to the city centre (82 per cent white) have seen their incomes rise more than 40 per cent above the average income. Both studies conclude that unless there is an increase in social and physical infrastructure investment 60 per cent of Torontonians will be living in poverty and the middle class will have virtually disappeared by the year 2025.

This alarming trend is corroborated by a recent info-graphic on provincial inequality produced by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. Their chart shows Toronto is second only to Calgary in income inequality.

This alarming trend is corroborated by a recent info-graphic on provincial inequality produced by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. Their chart shows Toronto is second only to Calgary in income inequality.

Furthermore, a new study by McMaster University and United Way Toronto: It’s more than Poverty: Employment Precarity and Household Well-being suggest more than half of Toronto area workers have fallen into “precarious employment.” These are part-time, contract, temporary jobs with no benefits. Although this trend is harder on those working at minimum wage jobs it is not restricted to low wage workers. Middle income workers are also dealing with precarious employment. Along with economic hardship, the global economy has brought more stress, doubt and anxiety about the future. Workers are finding it more and more difficult to plan for a family and retirement knowing they could suddenly and unexpectedly lose their jobs.

Twenty Five Years of Downloading from Higher Levels of Government

Public Transit Underfunding

Congestion, smog, stress, long commute times, increased respiratory illness, would not be with us today without decades of underinvestment and downloading by provincial and federal governments. This chronic funding shortfall must first be addressed in order to rectify the low priority public transit has received in the past.

Federal Underfunding

In June of 2007, a plan to build new transit infrastructure in the GTA was first announced under Move Ontario 2020 and the federal government was expected to contribute a minimum of 35 per cent ($6.3B) toward the $18-billion price tag. So far, Metrolinx has only received $300-million in federal funding for The Big Move. Despite the growing need for more public transit in Canada’s cities a dedicated source of revenue was still missing from the 2013 federal budget. What’s worse, even with indexing the gas tax fund for inflation, the net result of other reductions to infrastructure transfers, is a $1-billion funding cut for 2014-15. Canada is the only G8 country without a National Transit Strategy. The twenty two projects in The Big Move must have adequate, continuous federal funding.

In June of 2007, a plan to build new transit infrastructure in the GTA was first announced under Move Ontario 2020 and the federal government was expected to contribute a minimum of 35 per cent ($6.3B) toward the $18-billion price tag. So far, Metrolinx has only received $300-million in federal funding for The Big Move. Despite the growing need for more public transit in Canada’s cities a dedicated source of revenue was still missing from the 2013 federal budget. What’s worse, even with indexing the gas tax fund for inflation, the net result of other reductions to infrastructure transfers, is a $1-billion funding cut for 2014-15. Canada is the only G8 country without a National Transit Strategy. The twenty two projects in The Big Move must have adequate, continuous federal funding.

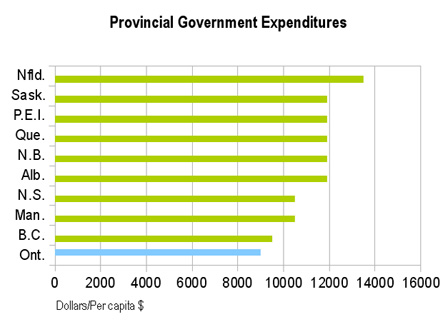

Insufficient Federal Equalization Payments to Ontario

With thirty nine per cent of the population, Ontario was once the economic powerhouse of Canada. However global restructuring, the high dollar, Dutch disease etc. has shed 255,000 manufacturing jobs over the past decade leaving us ill equipped to contribute to ‘have not’ provinces through federal equalization payments. An article in the Toronto Star by Mowat Centre for Policy Innovation director, Matthew Mendelsohn: Ontario staggers under burden of fiscal federalism, makes reference to the Drummond Report. Although the report looked at ways to cut spending, it also revealed Ontario has less money to spend per capita because of a $12.3-billion shortfall in federal transfers.

With thirty nine per cent of the population, Ontario was once the economic powerhouse of Canada. However global restructuring, the high dollar, Dutch disease etc. has shed 255,000 manufacturing jobs over the past decade leaving us ill equipped to contribute to ‘have not’ provinces through federal equalization payments. An article in the Toronto Star by Mowat Centre for Policy Innovation director, Matthew Mendelsohn: Ontario staggers under burden of fiscal federalism, makes reference to the Drummond Report. Although the report looked at ways to cut spending, it also revealed Ontario has less money to spend per capita because of a $12.3-billion shortfall in federal transfers.

While new premier, Kathleen Wynne announces, “the cupboard is bare,” we hear very little about Ontario being required to contribute the same amount to federal coffers despite being one of the provinces hardest hit by the recession. Mendelsohn concludes that if Canadians were aware that federal spending and transfers continue to take money out of Ontario, they would be offended. He’s right. For many years Ontario gave to ‘have not’ provinces. Federal equalization payments must address the hollowing out of Ontario’s manufacturing sector and public transit expansion is a good place to start.

Provincial Underfunding of TTC Operations

The TTC struggled to maintain and expand service when the 50 per cent of subsidy for public transit was removed in the mid-1990s. Aside from a few provincial contributions ranging from $100-million to $238-million from 2007 to 2009, nothing has changed. TTC fares now comprise the highest operation “subsidy” (70 per cent) of any transit system in North America. The only regular contribution that can be put toward operations is $162-million in provincial gas tax funding which when divided between new transit infrastructure and operations, amounts to $91.6-million – a mere 6 per cent of the TTC’s $1.5-billion annual operating budget. The province should return to subsidizing 50 per cent of TTC operations, as it did in the past.

Delivery of new transit infrastructure will automatically result in a demand for increased service and operations. If a 50 per cent subsidy were already in place, innovative, less costly measures could address traffic congestion immediately. Electrification of existing rail lines, dedicated bus lanes and continuous bus routes (destinations along Kingston Road can require up to four transfers) should be considered before tunnelling.

TTC Fare Increases and Service Cuts

Faced with a perpetual operating budget shortfall, City Council has responded with a “let the users pay” approach to the TTC. Last year, the TTC generated a $22-million surplus due to overcrowding from service cuts. This money could have been used to avoid another five cent fare increase in 2013. Instead it was funnelled back into City coffers. The majority on City Council fail to recognize the importance of adequately funding this “essential service.” With ridership increasing every year, we should be expanding service. Instead we abandon the “Ridership Growth Strategy” and punish transit users with fare increases, ignoring the fact that many can no longer afford to use the TTC.

Criteria for New Revenue Tools

Additional revenue tools must not add to the financial burden and stress of Torontonians bearing the brunt of government cutbacks, precarious employment, unemployment and lack of affordable housing. Each fare increase has the potential to disqualify a growing number of people in Toronto from using public transit altogether. Unless we make a concerted effort to re-orient municipal, provincial and federal funding to ensure accessibility for the most vulnerable members of our communities, we fail to bring about the kind of prosperity and well being we envision with The Big Move. They should also encourage public transit use, reduce pollution from cars, while generating sufficient revenue without duplicating existing municipal revenue tools.

Existing Revenue Sources

The City of Toronto currently uses property taxes, land transfer tax, land value capture and have considered using vehicle registration tax to generate revenue for capital projects. Since municipalities have limited options for generating revenue, Metrolinx should co-ordinate with the City to ensure that they do not duplicate any of these tools.

Proposed Revenue Sources to Expand Public Transit

Fare increases, transit fare restructuring, a utility levy and employee payroll taxes would do more to exacerbate the economic hardship that already exists in the outer areas of the GTA and for half of Toronto residents engaged in precarious employment, while the amount of revenue generated would be relatively small ($50 to $260-million). Therefore we do not recommend adopting these revenue tools. However, a regional sales tax in combination with fare reductions, free transit for seniors, social assistance recipients, the unemployed and during extreme weather alerts, would significantly increase public revenue, while addressing inequality.

Progressive Revenue Sources Not Considered

Personal Income Tax: consideration should be given to taxing incomes over $250,000. According to Joseph Stiglitz Nobel Prize-winning former chief economist of the World Bank, a three per cent tax increase on higher income Canadians would generate $2-billion whereas the same tax increase on incomes under $30,000 would only generate $154-million.

Federal Equalization Payments: there is a $12.3-billion shortfall in federal transfer payments to Ontario. Some of this money could be directed toward public transit.

Corporate Taxes: underfunding of public transit has been permitted while corporations have seen their taxes drop provincially and federally. Since 2004, the corporate tax rate in Ontario has gone from 14 per cent down to 10 per cent. Originally intended as an incentive for economic investment, it has had little effect. To the chagrin of Bank of Canada governor, Mark Carney, Canadian corporations have accumulated almost $600-billion which they refuse to put toward anything but bigger bonuses for their CEOs.

Metrolinx should make corporate taxes as a priority revenue tool since corporations will directly benefit from the increased productivity of shorter commute times and profitability from Ontario’s preferred infrastructure delivery model of alternate funding procurement (AFP) or public-private-partnerships (P3s). This does not constitute and endorsement of P3s however.

According to The Big Move Conversation Kit, a proposed 0.05% corporate tax increase would generate $210-million/year. However if it were increased another 2.5 per cent it could generate as much as $1.26-billion/year. This 2.5 per cent increase would still be 1% less than the 2004 corporate tax rate. Adequate, dedicated corporate taxes are strongly recommended. On their own, they generate nearly $2-billion/year and do not exacerbate inequality.

Transport Shifting Sources

The carbon emission tax, highway tolls, vehicle kilometres travelled charge, parking space levy reduce pollution and congestion while encouraging people to use public transit. They should be given consideration based solely on this outcome. Before proceeding with these tools however, existing public transit service must be able to meet new demand. Increased service, new bus routes and continuous service along arterial roads (destinations along Kingston Road require up to four different buses) must be provided along with these incentives to leave the car at home.

$34-Billion Investment Must Address Inequality

According to the 2012 Ontario Auditor General’s Report, the Presto Next Generation fare card requires all users to have a bank account with which to load a $10 minimum, or pay a $6 initial charge. Tickets for the Airport Rail Link could range from $20 to $30. Metrolinx and the City of Toronto must ensure that new and existing public transit infrastructure is accessible. Presto card users can apply for a fifteen per cent federal tax credit but must take transit for thirty one consecutive days to qualify. Instead transit should be free for seniors and the disabled, transit authorities should provide a low income pass and free transit on smog alert/extreme cold days.

Good Job Creation

Infrastructure expansion brings job creation and the opportunity to provide a real alternative to economic recession and inequality. Metrolinx estimates that, The Big Move will generate 430,000 new jobs and $21-billion in employment income or as much as 800,000 to 900,000 jobs and $110 to $130-billion. To create prosperity that is equitable however, these jobs must be local, fair wage, full time, permanent jobs with benefits and they must be directed toward immigrant and visible minorities in Toronto’s outer neighbourhoods.

However, the decision to go with AFP (Alternate Funding Procurement), could significantly reduce the number of good jobs that will be created. The TTC will only be allowed to operate four new LRTs under a ten year contract. Maintenance jobs will be controlled by the private sector although there may be some apprenticeships for youth through a Community Benefits Agreement. Had the TTC Expansion Department been allowed to oversee these projects as originally planned, all construction, operation and maintenance jobs would have been unionized or at the very least subject to the City’s fair wage policy. The province has no such requirement and once the contract is awarded to the private partner, providing good jobs is even less likely. Thus calling into question, who really benefits from this $34-billion investment?

“Often, when the private sector claims to be more efficient than the public sector, this really means cutting labour costs by laying off workers, using non-unionized instead of unionized labour, cutting wages, pensions and other benefits, or reducing hours or conditions of work. This is particularly common in service delivery P3s, where the private partner is handed a budget or part of a budget to deliver services previously delivered by the public sector in return for a share in any savings it can generate.”

— Asking the Right Questions: A Guide for Municipalities Considering P3s, John Loxley, Canadian Union of Public Employees, June 2012, page 24.

Metrolinx Needs More Democracy

Real And Meaningful Public Consultation

In exploring a vision of transportation for the next 25 years, there must be democratic checks and balances to ensure real and meaningful public consultation is conducted at crucial decision making points prior to the selection of revenue tools. For example there was no public input over the decision to eliminate fifty years of in house TTC Expansion Department expertise, or unionized maintenance jobs. There were no public meetings about the signing of the Master Agreement with the City to build four new LRTs, the decision to use Alternate Funding Procurement (AFP) or the decision to hire non-unionized workers for a portion of construction of the Eglinton Crosstown LRT.

It is imperative the public interest be protected when considering public versus public-private-partnerships delivery models. For instance, unnecessary cost overruns and delays with the Presto fare card (Presto initial cost $250-million – final cost up to $700-million) might have been avoided if the Provincial Auditor General had been allowed to review all value-for-money-assessments and contractual agreements beforehand. Since corporate confidentiality prevents public scrutiny, any future decisions to go with AFP for new transit infrastructure projects, should first be subject to a review by the Provincial Auditor General’s office.

Local Autonomy

In the past, the Province has threatened to withdraw funding if local municipal officials try to retain autonomy over construction of new public transit infrastructure in Toronto. However, in replacing the TTC Expansion Department for delivery of four new LRTs, we risk losing fifty years of valuable, in house expertise. Metrolinx must not ignore this valuable, local, public source of technical experience. Metrolinx must take steps to ensure we do not become overly reliant on the private sector to the point where we are no longer able to choose anything but public-private-partnerships. The Ministry of Transportation and Metrolinx must take a more open and co-operative approach with municipalities. No more threats to remove funding. No more back room deals.

Brenda Thompson, April 1, 2013. •