On September 7, 2012, Canadian Foreign Affairs Minister John Baird announced the suspension of all diplomatic relations between Canada and the Islamic Republic of Iran. This measure, Baird summarized briefly, entailed closure of the Canadian embassy in Iran, recall of all Canadian diplomats stationed in Iran, and a federal mandate that all Iranian diplomats, newly declared personae non gratae, leave Canada within five days.1

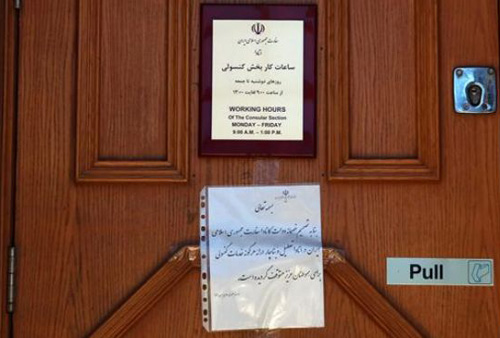

Canada is home to the world’s second-largest Iranian diaspora, after the United States. Until its closure last month, Canada housed one Iranian embassy, in Ottawa. More than 400,000 Iranian nationals relied on the embassy for passport renewal, consular services, and government documentation.2 Iranian nationals in Canada who are not landed immigrants regularly depended on the embassy, including approximately 3,250 Iranian international students who used it for translation services and to process their military service exemptions in order to keep their Canadian student visas.3 Tens of thousands of Iranians in Canada relied on the embassy for consular services to arrange travel between the two countries for leisure, business, and pressing family obligations. It remains unclear what the closure means for at least two Iranian-Canadians, Hamid Ghassemi-Shall and Saeed Malekpour, who are currently facing death sentences in Tehran’s Evin Prison.

Two days after Baird’s announcement, PM Stephen Harper defended the decision by citing Iran’s “capacity for increasingly bad behaviour.” Of Iran’s potential reactions to the embassy closure, Harper opined “nothing would surprise me.”4 As expected, major Israeli political players welcomed the decision. Israeli PM Benjamin Netanyahu, Foreign Minister Avigdor Lieberman and President Shimon Peres each released statements of support for Canada’s “courageous” and “moral” act in the diplomatic field.5 The Jerusalem Post highlighted Canada’s growing reputation among political pundits as “the new leader of the Free World and as Israel’s strongest advocate in international forums.”6 Also predictably, the Iranian Foreign Ministry spokesperson called the decision a “hostile” act by a “racist government” conducted in an “unprofessional, unconventional and unjustifiable manner.”7

Other Reactions

The decision provoked mixed reactions from other observers of Canadian Mideast policy, who are predominantly still trying to determine what the surprising announcement means for Canadian-Iranian relations and for the region. Former Canadian Ambassadors to Iran have called the move “stupid” and a “mistake.”8 Within the Iranian diaspora, the decision has brought to light deep internal political splits: prominent Iranian-Canadians have announced their preference for a downgrade rather than a termination of diplomatic relations, emphasizing the importance of dialogue and communication in times of geopolitical conflict; other more conservative voices argue that cutting diplomatic ties may allegedly allow for the advancement of democracy in Iran, and even compell the Iranian government to change its behavior. Meanwhile, many anti-war activists have emphasized the ways in which these political and diplomatic manoeuvres will militarize the lives of ordinary people.

The implications of the Harper government’s decision remain disturbingly ambiguous. While presented as a call for human rights and democratization, this extraordinary step has escalated regional tensions and discursively empowered calls for increased regional militarization. This is what ought to most concern people of conscience. At the same time, this announcement is not likely to effect a major political change in Iran: the decision to cut diplomatic ties with Iran reflects the Harper government’s desires for influence in the Middle East more than it reflects Canada’s actual clout.

Official Rationale

In his announcement, Baird went so far as to call the Iranian government “the most significant threat to global peace and security in the world today.” He cited five main justifications for cutting diplomatic ties with the Iranian regime: it provides increasing military assistance to the Assad regime in Syria; it refuses to comply with UN resolutions regarding its nuclear program; it routinely threatens the existence of the State of Israel; it is among the world’s worst human rights violators; and it protects and materially supports terrorist groups.9 Most students of Iranian domestic and foreign policy would agree that, to varying degrees, all of these allegations are true – but none are recent revelations. In fact, the Islamic Republic has been remarkably consistent for decades in its human rights violations, opposition to Israel, internal political instability, and support of non-state militant organizations. So, why the sudden stop?

When pressed for a more concrete explanation for the extraordinary move, Baird noted his concern that Canadian diplomats were unsafe in Tehran. To make this point, he referred to the 1979 American Hostage Crisis and the November 2011 storming of the British Embassy in Tehran, the latter of which “weighed heavily” on the Harper government.

Let’s put aside the insinuation that the Harper government has suddenly grown sensitive to events that occurred decades before its inception. Moreover, while the 2011 ransacking of offices and diplomatic residences of British officials in Tehran did cause Britain to withdraw its diplomatic staff, shut down the Iranian embassy in London and order the expulsion of all Iranian diplomats, Britain did not suspend its ties with the Islamic Republic. So, why the strong Canadian response? Granted, the Canadian Foreign Affairs Department recently revealed that it paid an international security firm almost $2-million for an intelligence study of potential threats to Canadian foreign embassies – the results of which might have informed the Harper administration’s decision.10 And Baird has since admitted that the decision to cut ties with Iran was in the works for months before its announcement.11 However, in a recent CBC interview, Baird also conceded that there had been no increase in the security risks to the Canadian embassy in Tehran or any direct threat.12 In the absence of a specific event or development to trigger the decision, Baird’s bleeding heart rationale inspires little trust.

Human Rights Is Not on the Agenda

From the standpoint of Canadian governance, there are principled reasons for putting political and diplomatic pressure on the Islamic Republic. Since Canada resumed normal diplomatic relations with Iran in the 1990s, opportunities to do so have included: the Iranian student massacres in July 1998, one of the most violent and widespread protests in the country since the Iranian Revolution; the 2003 arrest and subsequent beating, rape and killing of Iranian-Canadian photographer, Zahra Kazemi, and its attempted cover-up; and the intense and multifaceted repression of protesters and activists of the Green Movement during and after the fraudulent presidential elections of 2009. However, the Canadian government all but ignored these and numerous other outrages because its political and regional interests were simply not well served by diplomatic intervention at these times.

Despite Baird’s posture of compassion, this record of inaction indicates that human rights and democracy in Iran are not on the Harper government’s agenda. As many commentators have pointed out, the arguments Baird put forth for cutting diplomatic ties are actually good reasons to keep some level of exchange and interaction with the Islamic Republic; not to mention an actual presence in the country.

Further, if cutting ties is intended to motivate the Iranian regime to alter its policies and practices, a claim made by some Iranian-Canadian conservatives, then it is relevant that even Harper himself candidly admits that “[Canada’s] influence and that of our partners on Iran is minimal.” Similarly, Baird remarked, “Frankly, our ability to influence the regime in Iran has been limited for some time.”13 What Canadian officials were able to do from Iran, however, was to provide thousands of Iranian-Canadians with much-needed consular services and serve as eyes and ears on the ground – all of which may have come in particular use during the upcoming 2013 Iranian Presidential elections. Taken together, the Harper government’s decision to cease ties with the Islamic Republic appears to be rooted in other interests apart from the situation in Iran itself.

Smoke and Mirrors

The Canadian government benefits from cutting ties with Iran in several ways. First, it affirms Harper’s passionate and unwavering pro-Israel stance, which pleases his international allies. Second, it helps to strengthen Canada’s political influence in the region. As per Baird’s list of justifications, it was evident that the Harper government appears mainly concerned with Iran’s geopolitical actions vis-à-vis Israel and Syria, and concerned much less with Iran’s behaviour toward Canadians or Iranian nationals. Finally, and perhaps most significantly, in the context of an intensifying drive toward war, Canada has effectively removed itself as a resource and shrugged itself of political and ethical responsibility for citizens and residents in the country in the event of a military attack.

Importantly, Canada’s decision also benefits major power-holders in Iran. For the Iranian government – itself undergoing a deep-rooted legitimacy crisis due to its repeated violent repression of dissent and an escalating economic crisis – the Canadian announcement serves at least two purposes. Far from actually changing the regime’s practices, Canada’s announcement fits neatly in the Islamic Republic’s ideological puzzle as another instance of Western aggression. The regime will use the Canadian position as an opportunity to mobilize its social base and to inject Iranian society with further coercion and unrest. Moreover, the regime will exploit this development as an opportunity for increased internal and regional militarization – inflaming precisely those practices Baird decried.

Meanwhile, as the regime promotes the need for greater national security against foreign interference and a U.S.-Israeli attack, it will be Iranian dissidents, social justice activists and marginalized groups who will bear the brunt of the steadily increasing militarization of Iranian society. Importantly, the militarization of Iranian society has developed in tandem with neoliberal economic reforms of privatization and economic restructuring. Under Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, the regime’s neoliberal economic doctrines and subsidies have developed at an even faster pace than in the past – all with a crushing effect on social movements, particularly the Iranian workers’ movement.

Regional Implications and Anti-War Responses

Iran recently confirmed, for the first time, that it has military forces in Syria aiding Bashar al-Assad’s government in its fight against rebels and its multifaceted brutalization of ordinary Syrians caught in the crossfire.14 The rather candid announcement by the head of the Revolutionary Guards, followed with a warning that Iran would get militarily involved if its Syrian ally was attacked, is testament to the rapid escalation of geopolitical warfare in the Mideast.

Canada’s newly cut ties do not change this reality – or much else on the ground in Iran – but do empower calls for war. Therefore, in a political moment marked by intensifying preparations for military confrontation, wherein the major question for most observers is not whether but when there will be another war in the region, even the harshest critics of the Islamic Republic’s human rights violations cannot blithely support Canada’s decision.15 The Harper government has effectively boosted a kind of warfare that affects ordinary people first: Iranians in Iran who are bearing the brunt of the policies of their repressive government, the people of the region whose social fabrics will be frayed in the event of war, and Iranian-Canadians who are increasingly distanced from their lives in Iran, who will no longer have any representation if they travel back, and who are asked by xenophobic Canadians to give up their Iranian identities.16

Under these conditions, it is critical for Leftists and social justice activists to build a strong anti-war movement that is unequivocally anti-dictatorship. In the coming weeks and months various anti-war rallies will be held in our communities and cities, where we will be asked to limit our position on Iran to an ‘anti-war’ stance. But we cannot develop a ‘united front’ in a vacuum – ignoring domestic repression and regional events. This is not a cut-and-dry case of Western imperialist states ganging up on an isolated and innocent Middle Eastern state. Overlooking a sober assessment of Iranian state-repression in favour of relying on a simpler anti-imperialist political formula dramatically misrepresents the complexity of this geopolitical crisis. Politically consistent and responsible Leftist anti-war activists must rise to this challenge. •