The Student Movement: Radical Priorities

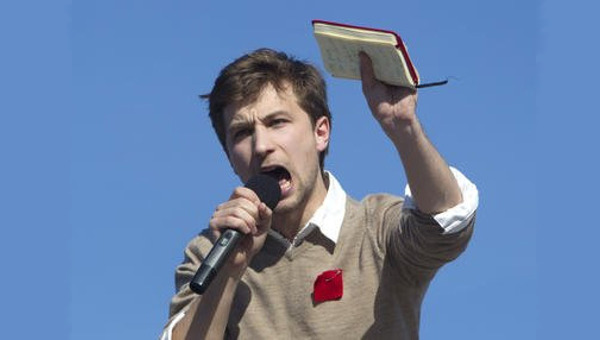

The student movement in Quebec is an incredibly important development, with implications that reach well beyond provincial borders. The movement emerged in response to a 75 per cent increase in tuition fees to be implemented over the next five years, but it has quickly evolved into something far more significant. “People are starting to realize that the real problem behind the rising tuition fees and the commodification of education is something related to a socioeconomic system that is behind it all,” said Frank Lévesque-Nicol, a spokesperson for a protest that was held on February 2, 2012. The student movement has rekindled the political imagination to a degree not seen since the Quiet Revolution of the 1960s. This is the most troubling and dynamic period in recent Quebec history, and the possibility that this energy will foster fundamental social change is very real.

The student movement is being treated as a single-issue by the mainstream media, and while one of the core demands is indeed for tuition to remain frozen, students have consistently framed and fought their struggle in broader social terms. The movement today is one of resistance and social change. People are refusing to pay for decades of corporate tax cuts, deregulation, economic crises and environmental exploitation. And while the conditions in Quebec are unique, many of the basic principles apply across Canada and most of the industrialized world. A spirit of political agitation, resistance and civil disobedience is emerging that will likely broaden in the months and years ahead.

Austerity and Class Struggle

There are reasons for the timing and emergence of these movements. Decades of policies that favour multinational corporations and discipline the broader public have reached new heights with the global economic crisis. Rather than seeking to ameliorate these conditions in light of the ongoing crisis, powerful interests have decided to exacerbate these trends. The official rhetoric is that people have to pay their fair share as nations struggle to exit from the global crisis. But the reality is that the public sector has incurred the necessary expenses to keep neoliberal capitalism alive – effectively lifting these costs from the corporations and banks – while imposing its environmental and social costs upon the people.

The Quebec case is revealing in this respect. The turn to austerity is part of a broader ‘cultural revolution’ that would bring the ‘sacred cows’ of the province pasture, to use the words of provincial finance minister, Raymond Bachand. The sacred cows to which Bachand is referring are accessible education, health care and other social programs, but a cursory look at federal and provincial politics reveals that the true sacred cows are multinational corporations, resource industries and financial interests.

Minister Bachand received a warm welcome from corporate leaders when introducing the tuition hikes as part of the 2012-13 budget at a luncheon organized by the Board of Trade of Metropolitan Montreal in April, 2011. Bachand took the opportunity to stress that corporate income taxes – among the lowest in North America – would remain untouched. Healthcare user fees would instead be introduced along with hydroelectricity fees and a 75 per cent increase in tuition fees. Universities will also be increasingly privatized under the Liberal education plan, as they would be required to significantly increase private funding and donations.

On the same day as the Board of Trade luncheon, tens of thousands of people were protesting against the budget in the middle of Montreal’s financial district. The contrast in this image was clear for all to see: a Liberal finance minister meeting with some of the wealthiest people in the province, while hundreds of thousands marched outside against the very policies being discussed in the luncheon. This image has come to typify the conduct of affairs in most liberal democratic societies. People are free to organize and protest, so long as they do not disturb the luncheon. The case for organized opposition and creative civil disobedience in these circumstances is compelling.

Broadening the Struggle

The speed with which the student movement broadened to a general social struggle is significant and worthy of replication elsewhere. Austerity budgets have been introduced in provinces and cities across Canada and the world, and the level of political organizing in opposition to these measures is promising. It is important to recognize that most of these initiatives are led by students and youth. As Noam Chomsky wrote in defence of the students in 1968, “the student movement today is the one organized, significant segment of the intellectual community that has a real and active commitment to the kind of social change that our society desperately needs.” The achievements of students and youth in the 1960s were significant, and they are certainly replicable, but the conditions and struggles being waged are radically different today.

“These assemblies affirmed the merits of syndicalist organizing, as the strength and effectiveness of the movement in Quebec rests upon highly localized student associations meeting regularly in their communities to adopt collective decisions.”

The student movement began gaining visible momentum in January 2012, as college and university student unions across the province started to adopt unlimited general strike mandates during their general assemblies. These assemblies affirmed the merits of syndicalist organizing, as the strength and effectiveness of the movement in Quebec rests upon highly localized student associations meeting regularly in their communities to adopt collective decisions. Implementing the strike was most effective where students organized within their own departments, rather than through larger centralized unions. The smaller departmental associations then send delegates to weekly congress meetings organized by La Coalition large de l’ASSÉ (CLASSE), which must wait for local assemblies to adopt positions before moving forward. The model is proving very effective. This same approach should be emulated elsewhere – in university departmental groups and associations along with public and private sector workplaces, for example.

Students received a boost of support when two of the largest public sector unions publicly endorsed the student strike, calling on their membership to join the national protest in Montreal on March 22. The protest drew roughly 200,000 people and may have been one of the largest marches in Canadian history. It was around this time that the movement clearly became a general social struggle. Streetlamps, windows, storefronts and balconies are draped with red felt squares that have symbolized the Quebec student movement since 2004, and dozens of people don the square on their lapels in a show of solidarity with the movement. Students organized solidarity actions with locked out Rio Tinto Alcan workers and with hundreds of Aveos employees who recently lost their jobs, and actions were also organized in opposition to the Liberal government’s controversial Plan Nord, which seeks to exploit natural resources on indigenous lands.

A major action is planned for Earth Day on April 22 that will be organized along internationalist lines in solidarity with environmental struggles across the world. Several internationalist solidarity actions have taken place in France, England, South Korea and elsewhere. The actions are simply too numerous to list. Queer and feminist groups have also had a visible and articulate presence within the movement, and autonomous actions and mass events have become a daily occurrence.

State Oppression

For many who are participating in the movement, these events have marked a decisive shift from dissent to resistance. As social movements grow in power and influence, it is clear that they are being met with increasing levels of state and corporate propaganda, manipulation, surveillance, infiltration and physical police oppression and brutality. Traditional measures of order in liberal democratic societies like work discipline, personal and household debt, mass culture, propaganda and social conformity are proving insufficient today, and the state is increasingly resorting to force. I am writing here specifically of recent developments in North America and Europe, as the democracy uprisings and revolutions in the Middle East and Northern Africa are far more brutal.

The first thing worth noting is that these oppressive measures have been in place for a long time, but they have largely targeted black, Latino, aboriginal and other communities that are the first to feel the effects of austerity and oppression. Racial profiling and police shake-downs are all too frequent in major urban centres, with women and children generally left to suffer the consequences. What makes the recent wave of state oppression distinct is that police are now openly targeting political actors. Police oppression is only receiving widespread attention today because it is on dramatic display and because predominantly white youth are now on the receiving end. Whatever the case, the primary function of both racial and political oppression is to maintain the existing social order through force.

One potential measure of the influence that popular movements and dissident groups yield is the extent to which they are targeted and oppressed. Thus, organized labour and socialist groups were the primary targets for surveillance and oppression in the 1960s. Unions, artists, intellectuals and elected state leaders all became the target of state action. Today, police are largely targeting grassroots organizations and self-identified anarchist groups. Montreal police recently established the Guet des activites et des mouvements marginaux et anarchistes (the GAMMA squad), which roughly translates to “surveillance of marginal and anarchist group activities.” The most expensive and elaborate covert police infiltration operation in Canadian history largely focused on grassroots organizations during the G-20 summit in Toronto. There are important reasons that explain this historical shift in police oppression.

Globalization, industrial outsourcing and union-busting in the 1970s and 1980s have considerably diminished the power and influence of organized labour in North America. With unions no longer serving as the sole conduit for political organization, autonomous political groups have come to fill the void. Looked at in this light, the widespread emergence of grassroots community groups and anarchist organizations is largely the product of neoliberal capitalism. As Marx wrote, “what the Bourgeoisie therefore produces, above all, are its own grave diggers.” These grassroots organizations are now some of the most active in terms of organizing, and there is a real need to establish strong links with these groups. They are at the forefront of political organizing today and on the receiving end of state oppression. One of the most important questions to ask moving forward is how to effectively organize within this increasingly oppressive climate.

Challenges and Priorities

There are some encouraging signs that social movements will continue to expand in the coming months and years. But the challenges are overwhelming, and there is also an emerging right-wing populism to contend with. There are nevertheless prospects and openings for serious change, and this is something new. The Occupy movement has effectively changed the contours of debate, and it has done so across a fairly broad stratum of society. It was unthinkable to hear mainstream commentators talking about capitalism, poverty and radical alternatives prior to the economic crisis and the Occupy movement. It is now possible to talk about these things in a meaningful way, and this is a political opportunity. While this is encouraging, it is certainly not irreversible. Efforts will be made to oppress, distort and co-opt this more radical discourse as the Occupy movement prepares to re-expropriate public spaces from the status quo. There is a need for supporters and participants of Occupy to dedicate time, energy and resources to insuring that the movement remains vibrant.

Another priority is the need to overcome fear and oppression in all its forms. State elites and media outlets are fostering rhetoric that is readily comparable with the McCarthyism of the Cold War era, according to Laurentian University sociology professor Gary Kinsman. The Conservative Minister of Citizenship and Immigration (or Minister of Deportation), Jason Kenney, has called the grassroots organization No One is Illegal a group of “hard-line anti-Canadian extremists,” while Natural Resources Minister Joe Oliver has singled out “environmental and other radical groups” as threatening to “hijack our regulatory system to achieve their radical ideological agenda.” Greenpeace and People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals have also been identified as “multi-issue extremist” groups. “The fact that they are even discussing lawful dissent under the heading of terrorist activity is obviously of immediate concern,” said Canadian Civil Liberties Association’s Abby Deshman of recent state and police rhetoric. Instilling fear in the population serves several useful functions: fear acts as a deterrent, discouraging people from engaging in political activity and civil disobedience. Fear also turns people to embrace authority and social order. There is a real need to find ways of overcoming this resort to fear.

Oppression is not merely taking the form of rhetoric. The Occupy and student movements were treated naively when they began, but youth are now pepper sprayed and beaten on a near-daily basis in Montreal and elsewhere. Police have begun to deploy riot squads immediately to dismantle actions, whereas some effort was made at conciliation in the past. “Our job, as police officers, is repression,” said the President of the Police Fraternity of Quebec, Yves Francoeur. “We do not need a social worker as a director, we need a general. After all, the police is a paramilitary organization, let’s not forget it.” It is wretched to say this, but the point has been reached where creative thinking is needed to figure out how to organize effectively in the face of increasing physical oppression.

One evident and encouraging trend following the crisis is the emergence of coalition-building initiatives that include unions, community organizations and more radical grassroots initiatives. The Greater Toronto Workers’ Assembly (GTWA) is promising, and the Quebec coalition that was established to resist provincial austerity is proving active and effective. Most of these initiatives have a strong student and youth-base at their core, which has generally served to push passive unions into engaging in popular and militant actions. This is all encouraging. One can only hope that these coalitions grow stronger and that unions start taking our present circumstances more seriously. A clear weakness in the student and Occupy movements is lack of militant activity from public and private sector unions. There was widespread hope that the Quebec student strike would broaden into a general strike, but none of the public and private sector unions adopted strike mandates that were possible. Unions need to start taking more meaningful actions, as youth cannot go this alone. Coordinated strike activity across sectors with strong and creative solidarity work is arguably necessary.

People also stand to learn a great deal from the student movement in Quebec, as the organizing principles and strategies developed by the movement are dynamic and highly effective. A widespread social movement could emerge by using these same organizing techniques in other regions, provinces and at the federal level. The basis of this strategy rests upon organizing locally within our communities. The principles of direct democracy are taken seriously, as people organize in small groups where meaningful discussion and decisions can actually take place.

More than anything, these ongoing struggles resoundingly affirm the need for solidarity. Political organizing and action put immense pressures on the mind, the body, our emotions, our social relations and our energies. Personal contact, meaningful dialogue and care for one another are vital. A little fun also never hurt. New and lasting friendships are being developed by standing together in solidarity, and this is the greatest strength our movements have. In the face of immense power and increasing oppression, people and youth in particular are showing incredible creativity and resilience. •