Saskatchewan Election 2011: the Looming Debacle

A reporter covering Tory Prime Minister Kim Campbell‘s campaign during the 1993 election likened it to watching a dog die slowly. Campbell replaced Brian Mulroney after his public support collapsed and she was punished for his sins, winning only two seats and 16 per cent of the vote.

Saskatchewan’s November 7, 2011 election recalls that image to mind – the whole campaign is like watching a dog die. There is no public engagement, little interest and even less hope that casting a ballot is worth the effort. The choice between Brad Wall‘s Saskatchewan Party and Dwain Lingenfelter‘s New Democrats is clear, but the differences are so marginal that it is hard to believe that anything important would change if Lingenfelter replaced Wall.

Lingenfelter knows he is losing and is determined to shore up the NDP’s core vote. Hence he has run a careful, low key campaign, focussing on practical economic and social issues that might resonate broadly with the public. Issues like rent control and affordable housing, improved health care, a children’s dental plan, more day care spaces and more generous subsidies, a tuition freeze and so on are all modest programs, but depend on getting a bigger share of the province’s resource wealth to finance such measures for the public good. This, on the face of it, should win broad support. Lingenfelter’s promise to undo the worst of Wall’s anti-union laws will shore up union support. And his promise to talk about sharing resource revenues with First Nations will shore up the NDP’s traditionally strong support among the aboriginal community. But in the absence of an engaging, polarizing campaign, will it succeed in getting the vote out in large numbers? Probably not.

The Turn to Neoliberalism

Lingenfelter’s problem is he carries too much baggage from the past to be credible as a born again moderate social democrat. He was Romanow‘s Deputy Premier who joined Finance Minister Janice MacKinnon in the U-turn away from social democracy to neoliberalism in the 1990s. He was a key member of the inner cabinet cabal which decided that the Romanow government’s biggest adversaries were trade unionists, environmentalists, committed party activists, and the general left. So they beat up on the NDP’s core constituencies as they implemented neoliberal cuts to social, health and education programs; reduced taxes on business, resource companies and the wealthy; and completed Grant Devine‘s privatization of key public assets. This past has come back to haunt Lingenfelter in Saskatchewan Party attack ads and Wall’s delight in quoting his former cabinet colleague, Janice MacKinnon, chastising Lingenfelter for his misguided economic policies and big spending ways.

Given all this, can the public really believe Lingenfelter would do any of the progressive things he is promising? Back in 1991 Romanow and Lingenfelter promised to reverse the neoliberal agenda and return to basic social democracy, only to break that promise in spades. And did Lingenfelter stay to fight the good fight when Romanow’s government fell to near humiliating defeat in 1999? No, off he went to become an Alberta oil executive.

Wall knows he is winning, and winning big. So he too is running a careful campaign, emphasizing fiscal responsibility and economic prudence. He is somewhat cynically running against his former boss, Grant Devine, when he proclaims Saskatchewan can’t go back to the dark days of disaster and debt of the 1980s, and accuses Lingenfelter of proposing measures that would do just that. Wall has increased spending on social, health and education programs enough to make the core right-wing of his own party, and key members of the business lobby, uneasy. Brad Wall, to them, seems a little too NDP-like in his approach to spending. But Wall saves himself by bashing unions and pushing the race hot button by carrying on hyperbolic rants about the NDP’s promise to talk resource revenue sharing with First Nations.

One thing Wall does not want is a heavily polarized, ideological campaign that goes after his right-wing record and tries to expose his right-wing views (does he have a hidden agenda to be trotted out upon victory?).

Progressive Vision for Saskatchewan?

To have any hope Lingenfelter needs to confront Wall and polarize the campaign around clear ideological lines with a clear and moving vision of what Saskatchewan could be. But the problem is that there are not many ideological differences between Wall and Lingenfelter on the big, important questions. Lingenfelter wants an extra nickel on the dollar from potash – literally raising it from a nickel to a dime. For the first time Saskatchewan’s debate on resource revenue sharing has become a matter of nickel and dime politics. What Lingenfelter should be demanding is 50 cents on the dollar, and an aggressive program of developing a public ownership presence in all Saskatchewan’s resources. Then the sparks would fly. It is no accident that the resource wealth issue got big play in the leaders’ debate – it resonates deeply with the public and always has. The public knows in their heart of hearts that they are taking a bath on sharing of Saskatchewan’s resource wealth.

There is another much more practical reason for the NDP to provoke a polarized, confrontational campaign. This has been a two party race, and that spells trouble for the NDP. The NDP only won over 50 per cent of the vote in four elections: 1944, 1952, 1971, and 1991. All other victories resulted from divisions in the free enterprise, anti-NDP vote. The Liberals, who won 20 per cent in 1999, 14 per cent in 2003, and 9 per cent in 2007, are effectively out of the running. This poses a tactical problem for the NDP – where will those 42,000 2007 Liberal votes go? The NDP knows the Green Party will siphon off a few thousand votes of those who would otherwise tend to vote NDP (over 9,000 in 2007). But where will the Liberal vote go? Will it stay at home, or go with the smiling Wall? The fact is that the only way to win the votes of Liberals worried about the Saskatchewan Party is to confront and polarize. Given this campaign, most of the Liberal vote willing to go NDP in a ideologically polarized campaign will probably stay home. This is just another reason why Wall is so confident of a smashing victory – a two-way fight and a quiet campaign to keep the moderate Liberals asleep.

But such an approach would be confrontational, polarizing, and high-risk. The fact is that Lingenfelter, and today’s NDP, are unwilling to play high-risk, principled politics.

Wall certainly does not want a campaign that attacks his pro-business, right-wing ways; exposes his piecemeal dismantling of the Crowns; accuses him of having a long-term, right-wing agenda including a relentless attack on the Crowns. He wants to slip quietly and easily into an overwhelming mandate, a mandate with a large number of Saskatchewan Party MLAs and a tiny leaderless NDP Opposition.

Then we shall see who the real Brad Wall is. Does he really just want to be Premier or is he a Harperite right-wing ideologue eager to reconstruct Saskatchewan?

At this point, Wall appears to be a guy who just wants to be Premier forever. But maybe not. And we can never forget who is behind him – a political coalition of old far-right Reformers, hard Tories, right-of-centre Liberals, and the business lobby. Some among these elements are already quietly critical of Wall for failing to deliver the right-wing goods. After the election they might demand that Wall pony up if he wants to stay on as premier. •

Party In Troubletown

J. F. Conway

Since Brad Wall’s 2007 victory, the slow, inevitable death of the Saskatchewan NDP has been painful to watch. The final funeral preparations began with the election of Dwain Lingenfelter as leader, an act of self-destruction by a party that, given its long and successful history, should have known better. And now, as we move toward the November 7 election, the casket is finally heading for the graveyard.

The sadness of the spectacle is heightened by the triumphs of the federal NDP. Under the late Jack Layton, the national party broke through to become the Official Opposition. Yet here in its Saskatchewan birthplace, the once proud CCF/NDP – the “natural governing party” of the province since 1944 – is about to experience its worst showing since 1938, when the CCF won 10 seats with just under 19 per cent of the popular vote.

Let’s look at the record. Since the CCF’s 1944 victory, there have been only three elections in which the party won less than 40 per cent of the vote.

Decimated by Grant Devine’s Tory sweep in 1982, the NDP won 38 per cent and nine seats. In 1999, NDP Premier Roy Romanow lost to Saskatchewan Party leader Elwin Hermanson by 3,557 votes, winning 39 per cent of the vote and 29 of 58 seats. Though the Saskatchewan Party outpolled the NDP, it won only 25 seats, allowing Romanow to cobble together an alliance with two of the four elected Liberals.

In 2007, NDP Premier Lorne Calvert fell to Wall and the Saskatchewan Party, winning 37 per cent of the vote and 20 seats. Wall’s Saskatchewan Party took 38 seats with 51 per cent. And now, 2011. If the published polls are more or less correct, the NDP faces annihilation on November 7. The polls suggest Wall is even more popular than he was in 2007. He’s helped by the fact that Saskatchewan’s economy has performed beyond expectations, comparing favourably to even the richer provinces.

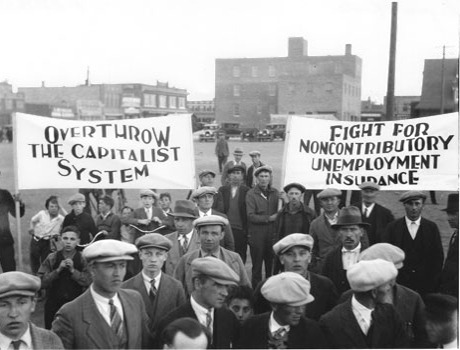

Recent Occupy Saskatoon protests.

The NDP’s numbers, meanwhile, have tanked to just under 30 per cent, while Lingenfelter is seen as best premier by a dismal 17 per cent (compared to Wall’s 73 per cent).

If the voting day scenario comes even close to these numbers, the NDP will be deeply humbled. In 2007, the NDP took 10 of their 20 seats with over 50 per cent of the vote, and three with over 60 per cent. This constitutes the party’s core of 13 ‘safe’ seats. Given the current polls, the NDP can forget the seven close seats it won in 2007. And if the party dips below 30 per cent of the popular vote, the NDP can kiss goodbye most of the 10 seats won with over 50 per cent.

The three 60 per cent seats – Cumberland, Regina Elphinstone-Centre and Regina Walsh Acres – would probably stay in the NDP column. But politics is a bit more complicated than simply translating poll numbers into votes and seats on election day. The Wall government is riding high but there are some warning signs for it.

The Role of Organized Labour

Brad Wall’s aggressive war on unions [see Bullet No. 239] has ensured that organized labour will work very hard in the election. He’s offended teachers, professional and non-professional health workers, and SIAST instructors, among others. Together, this is a very large number of unhappy people, all of whom have families, friends and neighbours.

On the economic front, Wall has spent wildly, banking on continuing high resources revenues. But prices for resources have been falling on commodities markets and the future looks very scary. Wall’s spending and the decline in resource revenues has created a growing deficit, but the full story will stay under wraps until after the election.

Wall’s huge popularity and talk of the NDP’s looming decimation might also give swing voters pause, leading to a vote for a strong opposition to keep the Saskatchewan Party in check. Wall’s campaign could sag and the NDP’s could take off – especially if Lingenfelter is downplayed in favour of ‘the NDP team.’

Given these uncertainties, I would still forecast an easy Wall victory but the NDP could hold the vote in the mid-thirties and take eight to 12 seats.

On the other hand, the NDP could slip below 30 per cent and win only three or four seats.

This outcome became inevitable when the NDP picked Lingenfelter as its leader. There’s no need to go over the details of Lingenfelter’s old style, right-wing “take no prisoners” approach to internal party politics – everyone knew Lingenfelter’s history and the role he consistently played in the NDP over the years.

Lingenfelter wants to be premier and he has always wanted to be premier. This became an obsessive life goal, and he was prepared to play whatever kind of politics was necessary to achieve it. This was not just an ambition, something we can all understand in a politician – it became a sense of entitlement. Lingenfelter believed he was entitled to become leader of the NDP, and entitled to become premier.

Lingenfelter expected that when Lorne Calvert took over from Romanow after he stepped down after the 1999 debacle, he just had to wait a few years. Everyone thought Calvert was doomed in 2003. Then Calvert would step down and Lingenfelter would take over and beat Hermanson in 2007.

Calvert surprised everyone, including himself, by winning. And Lingenfelter had to languish in the wings until Calvert lost to Wall in 2007.

When he won his tainted leadership victory (no need to rehash it all again here), Lingenfelter was shocked that this guy from nowhere, Ryan Meili, came a strong second. Now, one would think that a person who is so popular among party members that he comes a strong second should be embraced and cultivated, encouraged to gain a seat, and invited into the inner planning circles. But no, in Lingenfelter’s world this person had to be stopped, so Lingenfelter’s forces in the party ensured Meili failed to get a nomination. He was finally driven from the NDP (though I hear he might be making a comeback).

Will the NDP recognize that the train wreck about to happen on November 7 is of their own making?

A wiser course for the party would have been to tell Lingenfelter, this animated corpse from the past, to step aside in favour of someone like Meili, someone from the new generation with new ideas and new approaches to politics. With a Ryan Meili as leader, the NDP could have begun a rebuilding process looking forward to the 2016 election.

Now the NDP faces an electoral disaster under a tainted leader from the past. Will Lingenfelter go willingly after the defeat, or will he create a leadership mess?

Whatever happens, the party’s next leader will have to start a rebuilding process that should have begun in 2007, when the NDP took a detour down memory lane with Lingenfelter.

Brad Wall is no doubt delighted. He’s probably convinced a third term is pretty much a sure thing. He might be right. •

The second article first appeared on the Planet S website.