Harper in Honduras: Left Solidarity and the Future of Coup Resistance

It must have been a struggle for Honduran coup-President Porfirio ‘Pepe’ Lobo to keep a straight face during his recent press conference with Canadian Prime Minister Stephen Harper on August 12, 2011. After all, even Lobo’s supporters have never gone so far as to claim – as Harper inexplicably did – that the man who was installed as President after a military coup, fraudulent elections and a violent and murderous crackdown on dissent was “a prominent human rights leader in this country.”

Lobo certainly didn’t attain his credentials as a human rights leader while he attended business school in Miami or when he took up his wealthy landowning family’s cattle ranches in Olancho, or in his long relationship with the Honduran National Business Council (COHEP). And it’s unlikely that anyone would have called the positions he took during his tenure in Congress – his insistence on reintroducing the death penalty, for instance – to come from a preoccupation with human rights. Most notably, in his eighteen months as de facto President, his name has only ever been connected to human rights when he has been accused of coordinating a systematic and brutal campaign of state terror that continues to this day. Naturally, this didn’t stop Stephen Harper from claiming that he shared with Lobo “a relationship based upon a commitment to human rights, democracy, security and prosperity,” which will no doubt be reinforced by the 150 soldiers Canada is sending to Honduras to conduct joint military exercises.

‘Honduras is Open for Business’

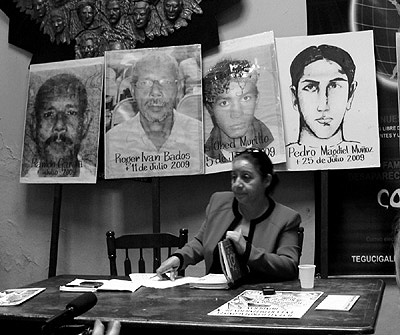

In June 2009, the Honduran military kidnapped then-President Manuel Zelaya and flew him out of the country, setting off a wave of popular resistance and state repression that quickly led to a complete military lockdown and a descent into utter impunity for a violent police apparatus. Over 200 people have been killed and many hundreds of others have been attacked, injured, tortured and otherwise terrorized in an effort to stamp out dissent. The press was immediately and violently muzzled and remains so; not only have media outlets had their offices ransacked and equipment broken, but journalists have been subject to intense repression. Reporters Without Borders has called Honduras one of the most dangerous countries in the world for journalists, noting that dozens have been killed or threatened; sometimes the cruelty is unimaginable, as when critical radio journalist Enrique Gudiel came home in February 2010 to find his seventeen-year-old daughter hanged.

Meanwhile, the state apparatus was purged of any elements deemed to be a threat to the new far-right reality, from criminal court judges like Maritza Arita Herrera, who had the nerve to rule in favour of anti-coup student activists, to the head of the Honduran Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH), Darío A. Euraque, whose department was accused of “indoctrinating” racial minorities with the idea that they should participate in writing and celebrating their own cultures. And now, with their enemies marginalized and on the defensive, the oligarchs who rule Honduras are pursuing a ruthless neoliberal agenda that is ravaging the already heavily exploited Honduran people: crushing strikes and breaking unions, offering up natural resources like rivers for major construction projects, establishing corporate city-states, selling off public utilities and empowering foreign investors to carve up traditional Garífuna (afro-indigenous) and campesino lands to exploit as they see fit. This shameful crusade reached its nadir in May 2011 with the aptly titled “Honduras Is Open For Business” conference, during which the coup regime fell upon itself to show foreign investors that Honduras was for sale.

And at the centre of it all stands President Pepe Lobo, grinning and shaking hands with Stephen Harper. And they have reason to smile; the situation in Honduras is working out well for both of them. For Lobo and his friends in the oligarchy, the coup has succeeded. The golpistas (coup-makers) were defiant in the face of an initial wave of international remonstrations of the coup and, with the help of U.S. and especially Canadian diplomatic leverage, used fraudulent elections and a sham truth commission to rebuild their legitimacy such that they have now been re-admitted to the OAS and are being reintegrated into the international community. At the same time, they orchestrated a campaign of state terror that was effective, in part, because rather than committing large-scale massacres that would draw international attention, it targeted movement activists in their homes and workplaces and served to instil a profound sense of fear that has convinced many Hondurans to stay away from anti-coup activism.[1]

For Harper and the Canadian owners of businesses in Honduras, their friendship to the coup regime – when most of the world rightly condemned it – has earned them a new free trade agreement that will undoubtedly strengthen the already powerful position that Canadian businesses hold in that country and lead to even greater profits being taken from it. Canadian businesses currently invest some $600-million in Honduras, and the new free trade agreement will ensure that an even greater share will flow in – and quickly back out – of Honduras in the future, leaving a swath of ecological and social destruction in its wake. Already the complaints against Canadian businesses are innumerable: notorious mining giant Goldcorp, known for ordering assassinations and violence against union organizers, has been leeching cyanide into the Siria Valley, infecting countless mineworkers and community members with ongoing health problems. Canadian ‘porn king’ Randy Jorgenson is implicated in what some have called the ‘ethnocide’ of Garífuna communities, on whose land Jorgenson’s company and others are building massive tourist resorts. Montreal-based Gildan – the largest private investor in the country – is infamous in Honduras for a litany of abuses connected to its sweatshop factories in tax-free maquiladora zones.

Gildan: A Good Corporate CItizen?

Not coincidentally, Stephen Harper’s visit to Honduras was not hosted in the capital city, Tegucigalpa, but in San Pedro Sula, the centre of Honduran industry and a convenient base for Harper to visit one of Gildan’s facilities in Choloma, a maquiladora-zone in Northern Honduras where foreign companies are exempt from the usual labour and environmental codes and operate in a tax-free haven. “As a general rule, our Canadian companies have a very good record of social responsibility,” said Harper as he toured the facility. “[Gildan] pays above minimum wage. It runs health, nutrition and transport programs for its employees and is a very good corporate citizen.”

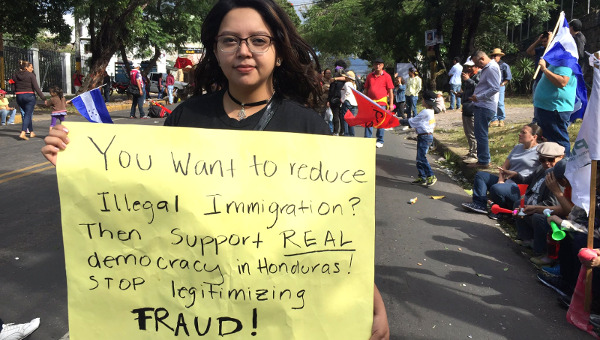

He was so busy gushing over Gildan’s benevolence that he didn’t take notice of the demonstration that had gathered outside the Expocentre where he and Lobo were signing the free trade agreement. The gathered protestors carried banners and placards admonishing Gildan and other Canadian companies and denounced Harper as a golpista in spirited chants. Among the gathered were a group of Honduran women who work for Gildan, who attempted to deliver an open letter to Prime Minister Harper. The letter, which Harper ignored, painted a very different picture of Gildan than that of Harper’s “good corporate citizen.” The detailed letter, drafted by the Honduran Women’s Collective (CODEMUH) explained:

“Prime Minister Harper, there have been constant reports of Canadian company Gildan Activewear’s anti-organizing and anti-union policies, among other labour violations. For example, Gildan El Progreso in Honduras closed in 2004 to avoid the certification of a union… other reports have surfaced of violations of other human and labour rights of workers, such as the right to live without violence, the right to work, health and life.

“Presently, Gildan Activewear is contravening the legal regulations for labour, with regards to treaties and international conventions that protect occupational health and safety, by implementing 4×4 shifts in their factories, where workers work for 4 days straight, 11.5 hours per day, and then have 4 days off. With this system, it’s common that on their days off, workers do extra hours, up to 2 day shifts or 2 night shifts. This means that the workweek can be 69 hours long, with a salary of $89.99 (U.S.) (L$1700 Lempiras) per week.

“The production goals or quotas imposed by Gildan Activewear are the highest in the industry in Honduras. To earn $89.99 per week, workers have to produce 550 dozen pieces every day, and are exposed to awkward postures, executing up to 40,000 repetitive movements in their joints, tendons, and muscles per day. These conditions produce Occupational Musculoskeletal Injuries (MSI)…In Honduras, Gildan does not pay taxes because they are exempt, so it is absurd when we see that a company with such a high level of exploitation of the work force has been applauded as one of the 50 best Canadian corporations and one of the 20 most responsible companies.”[2]

“To earn $89.99 per week, workers have to produce 550 dozen pieces every day, and are exposed to awkward postures, executing up to 40,000 repetitive movements in their joints, tendons, and muscles per day.”

Gildan represents only one example of Canada’s shameful corporate behaviour in Honduras, and yet these are the very companies that Harper is representing by so aggressively supporting the repressive Lobo regime. Indeed, Canada’s engagement with the coup government in Honduras is partly predicated on that very repression; recognizing that the military regime would be a better friend to its interests than any other in Central America, Canada broke off talks with the CA4 (Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador and Nicaragua) shortly after the coup in order to focus on a bilateral deal with the golpistas in Honduras. Details of the deal have not been made public, but it is reasonable to expect that the agreement will further empower companies like Gildan, who already terrify and exploit their employees; as Juana López Nuñez, a Gildan employee with chronic and debilitating pain caused by overwork, told Dawn Paley, “[workers] here don’t want to talk…they are scared to talk to the management because they think they will get fired or get a lower grade of pay.”[3] Now, Canada will likely use its deal with Honduras as a model for those it will push on the rest of Central America.

The Future of the Frente

But if Canada’s imperial aspirations in Honduras are clear, the form that the resistance will take is not. The movement that coalesced in opposition to the coup – the FNRP or Frente – was always a loosely organized collection of groups rather than a single unified entity. The energy with which it responded in the immediate aftermath of the coup, the fraudulent elections and the inauguration of a false president was remarkable and inspired. But as time has passed, the repression has been relentless and fierce and the international community has increasingly turned a blind eye, leaving the Frente to sustain its non-violent opposition – in the face of intense state violence – largely on its own steam.

Not surprisingly, the united front against the coup has been difficult to maintain, especially as the context has shifted in the last six months. The signing of the Cartagena Accord in May 2011 secured the return to Honduras of exiled President Manuel Zelaya and was the final step in the coup regime’s reintegration into the international community. The Accord offered guarantees of a variety of social and political rights that Hondurans ostensibly already have under the Honduran constitution; the same rights which the regime has demonstrated, before and after the signing of the Accord, that it will not uphold. As a result, many in the Frente consider the Accord little more than a ploy to bolster the regime’s legitimacy without dismantling the apparatus of state terror that keeps it in power.

Demonstrators in Tegucigalpa remain steadfast in their insistence on re-founding Honduras by democratic and nonviolent means. |

But the more worrying effect of the Accord could be the splits it has encouraged within the ranks of the Frente. Zelaya’s return puts him at the centre of the movement again; he retains a great deal of popularity as a friend of Honduras’ poor and the victim of the coup, even if the former is exaggerated and the latter an accident of history. The gathering of people to welcome him back to Honduras was, according to Canadian journalist Jesse Freeston, the largest public demonstration in Honduran history. Zelaya and his closest supporters – largely centre-left liberals from privileged classes – have used his return to push the Frente toward an electoral strategy, suggesting that the Frente become a political party and run Zelaya as a candidate in 2013 elections. However, the more radical forces within the movement – often those that represent the poorest and most marginalized within Honduras – have rejected this path, insisting that the Frente must resist the coup and re-found Honduras from below, through mass mobilizations and grassroots struggle.

This latter position has, more or less, framed much of what the movement has done in the past two years, but the return of Zelaya and the relentless repression that dogs even the smallest activist projects[4] has pushed the Frente into adopting the electoral strategy, though not without significant dissent. At a meeting of over 1500 delegates in June 2011, with Zelaya present and dominating the discussion, it was agreed that the movement would create a Frente Amplio (FARP) political party. There was no question that this was the will of the assembly; the period prior to Cartagena has been one of the hardest since the coup, especially given the disheartening defeat of the teachers’ strike, and Zelaya’s return gave the movement a shot of energy that it desperately needed. But many of the more radical delegates expressed disappointment at both the electoral strategy, which validates the corrupt political system that brought Lobo to power in 2009, and at the less-democratic manner in which the assembly was conducted, with Zelaya and his mostly male supporters dominating the microphones in a tight three-hour schedule.

The Canadian Left and the Split in the Frente

Even as these debates play out in Honduras, they are reflected in the debates within the Canadian left, which is united in its opposition to Canadian imperialism in Honduras but divided on what its solidarity with anti-coup forces should look like. On one hand, John Riddell and Richard Fidler have suggested that the return of Zelaya – whose popularity is at an all time high – is a partial victory in a context where victories have been few, and that his presence will embolden the resistance. In a piece co-authored with Felipe Stuart Cournoyer, Riddell acknowledged that there was no guarantee the Lobo regime would follow the terms of the agreement, but that the agreement provided another lever through which the Frente could assert its rights in Honduras. Fidler has also noted that opening up another avenue of struggle – engaging in an electoral process with Zelaya at the head – could be an important way of supporting the activist work seeking to re-found Honduras. After all, the movement has shown no desire to overthrow the state by converting into a guerrilla struggle; as such, popular demands to rewrite the constitution and dismantle the repressive police apparatus would necessarily require a state that was willing to hear and reflect popular will, and Zelaya is much more likely to fulfill that role than Lobo, especially if Zelaya’s political base for the elections is located in the Frente.

On the other hand, Todd Gordon and Jeffrey Webber have insisted that Cartagena serves to weaken and divide the movement while simultaneously casting a “democratic veneer” over the regime’s continued atrocities. Reintroducing the ambitious and opportunistic Zelaya marginalizes the activists who form the political centre of the movement, reducing the image of the Frente to an appendage of Zelaya, who is not rooted in popular struggles and only became part of them when he was overthrown in the 2009 coup. Gordon and Webber ground their position in the recognition that some of Honduras’ most important and activist groups – COPINH, for instance[5] – are those most marginalized by, and least interested in, a Zelaya-headed united front to win elections in 2013. Indeed, Zelaya’s participation in the Cartagena Accord, which paved the way for the coup regime’s reintegration into the international community, and his expressed willingness to work with coup-leader Lobo in pressuring for reform, only emphasizes the fact that he is not, and was never, a member of the movement he claims to lead. Zelaya’s government, prior to the coup, was progressive only compared to the utterly merciless brand of military neoliberalism imposed by Lobo and his far-right allies; there is no reason to expect that a Zelaya victory in 2013 would address the most important demands of the movement.

None, that is, unless the Frente could find a way to maintain the strength of its conviction to build a movement to re-found Honduras along more just, equitable and sustainable lines while, at the same time, supporting efforts to put its own candidates into the government. Nearly two years into Lobo’s term in office, he and his North American allies have gained, not lost, international legitimacy. The prospects for re-founding Honduras by having Lobo internationally isolated and domestically harried by protest and social upheaval are beginning to seem bleak. Though courageous and inspiring, the movements that coalesced into the Frente do not have the strength or the desire to raise their level of militancy. Lobo remains strong despite massive demonstrations, crippling strikes, land occupations and a variety of other forms of direct action against his government, and even radical groups at the centre of it all have acknowledged, as COPINH did last month, “that the situation in Honduras is getting worse and there exists very real possibilities for it to culminate in further crimes.”[6]

More of the same will not bear fruit, and if an escalation of militant resistance is what is needed to shift the balance of power, one is left to wonder what form of escalation is available. Any hint of armed struggle would be swiftly and brutally put down by the now confident and empowered military/police apparatus at Lobo’s command and, given the horrific memories of the civil wars in Central America in the 1980s, it is unlikely that such a suggestion would even be raised. Already, Zelaya’s speeches often begin or end with “golpe de estado, nunca mas,” meaning “never again” to a coup d’etat. The coup, then, according to Zelaya and his followers has succeeded; the challenge now is to find a different path to a new Honduras.

As such, the electoral path cannot be dismissed as easily as Gordon and Webber suggest. Nonetheless, the warnings they raise – warnings that are expressed by key figures in social movements that pre-date the Frente – must be taken to heart by those of us seeking to support the movement from the outside. A Zelaya presidency in 2014 would shift the political terrain slightly in favour of those who are struggling for a better Honduras, but it would not, in itself, alter the social, political and economic structures that make Honduran society profoundly unequal and unjust. Nor, indeed, would it alter the regressive dynamics that still pervade many activist spaces; machismo, patriarchy and racism are just a few of the problems associated with Zelaya’s caudillismo (strongman leadership) and the supporters it attracts.

A victorious Zelaya, then, would have to become – as he was prior to June 2009 – the target of the movements’ energies, not its representative. For activists outside of Canada, there must continue to be a concerted effort to support grassroots and community organizing, rather than blanket endorsements of Zelaya’s Frente Amplio. These include the women working in Canadian garment factories demanding an end to sweatshop exploitation. They include the campesinos of the Aguán Valley demanding access to farms that were stolen from them by Honduran oligarchs. They include Garífuna activists who are watching their traditional lands seized and carved up by Canadian tourism magnates bent on exploiting Honduras’ tropical climate and virtually non-existent tax regimes.

The Cartagena Accord and the return of Manuel Zelaya have undeniably strengthened the immediate positions of the coup regime and its allies, and Stephen Harper’s visit last week only crystallized that fact. His arrogant declaration that Canada has “no information to suggest that [human rights abuses] are in any way perpetrated by the government” is a slap in the face to the hundreds of Hondurans who have received violence and intimidation as a direct result of their involvement in the Frente or in anti-coup activism. But it is also a sobering reminder that the Lobo regime and its allies are taking full advantage of a resistance movement that is not strong enough, in this moment, to stem the tide of the far-right onslaught that Lobo’s regime represents. Our solidarity with the Honduran resistance will have to understand the limitations of both a Zelaya-fronted electoral program and a politically pure ‘politics from below,’ neither of which can – on its own – carry out the project of re-foundation that Hondurans so desperately need. •

Endnotes:

1.

The extent to which Honduran opposition to the coup has gone unexpressed is impossible to calculate, but it is certainly clear from my own interviews and conversations that many Hondurans have avoided anti-coup activism not because they support the golpistas but because they fear them. In November 2009, the military sent letters to mayors across the country demanding a list of names of people associated with anti-coup organizing; actions like this have served to create terror which has kept many people away from demonstrations that they would otherwise support.

2.

CODEMUH, “An Open Letter to Harper from the Women of Honduras,” August 12, 2011.

3.

Quoted in Dawn Paley, “Unfinished Business: Sweatshops, oligarchs, and the fear of a new constitution in Honduras,” Briarpatch Magazine, May 5, 2010.

4.

The scale of the repression makes it impossible to adequately reproduce here, but to give just one example: landless campesinos in the Aguán Valley have spent the past two decades building a legal case around claims to land currently controlled by Miguel Facussé (one of Honduras’ wealthiest businessmen and a close associate of Pepe Lobo). The land was recovered from a former U.S. military base and, after many years of struggle, was to be redistributed through the National Agrarian Institute (INA). After the coup, Facussé began using private security and paramilitaries to attack and intimidate the campesino families who lived and worked on the land, beginning what has become essentially a siege against poor and unarmed farming families. When called to respond to paramilitary killings – over 40 people have been assassinated by Facussé’s private army in the past two years – the police have only helped the paramilitaries in carrying out the so-called ‘evictions.’

5.

The Civic Council of Popular and Indigenous Organizations of Honduras (COPINH) is one of Honduras’ most radical and consistent activist organizations. They responded to the Cartagena Accord by writing an open letter to the OAS detailing the litany of abuses the coup regime has conducted – assassinations, abductions, illegal detentions, torture, evictions, intimidation leading people to flee the country – in just the past months, and holding the OAS responsible as an accomplice to those crimes for reintegrating the regime into its ranks solely on the basis of Zelaya’s return.

6.

COPINH, “Impunity and Human Rights Violations Reign in Honduras,” July 19, 2011.