Globalization And Its Consequences

Although capitalism has always been a global system, the international integration of production and finance and our dependence on cross-border activities seems greater than ever before. At the risk of oversimplifying, we now have a world system within which Latin America, Africa and the Middle East specialize in the production and export of primary commodities, increasingly to East Asia. East Asia operates as the world’s manufacturing hub, exporting final products to the developed capitalist world, especially the United States. And the United States specializes in providing the finance that underpins the international production system and developed capitalist country consumption.

While this global system has done little for popular well-being, elites have clearly profited. As the Wall Street Journal reports:

While this global system has done little for popular well-being, elites have clearly profited. As the Wall Street Journal reports:

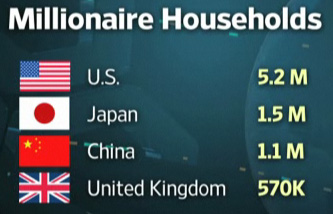

“According to a new report by Boston Consulting Group out today, the number of millionaire households in the world grew by 12.2 per cent in 2010, to 12.5 million. (BCG defines millionaires as those with $1-million or more in investible assets, excluding homes, luxury goods and ownership in one’s own company).

“The U.S. continues to lead the world in millionaires, with 5.2 million millionaire households, followed by Japan with 1.5 million millionaire households, China with 1.1 million and the U.K. with 570,000. Singapore leads the world in ‘millionaire density,’ or the percentage of millionaires, with 15.5 per cent of its population now millionaire households.

“The most important trend, however, is the global wealth distribution. According to the report, the world’s millionaires represent 0.9 per cent of the world’s population but control 39 per cent of the world’s wealth, up from 37 per cent in 2009. Their wealth now totals $47.4-trillion in investible wealth, up from $41.8-trillion in 2009.

“Those higher up the wealth ladder also gained. Those with $5-million or more, who represent 0.1 per cent of the population, controlled 22 per cent of the world’s wealth, up from 20 per cent in 2009.”

China’s Unique Position

This growing concentration of wealth is increasingly underpinned by the globalization process itself. Corporate mobility creates a framework within which governments compete for investment by offering the most attractive labour conditions possible. That translates into a race to the bottom in terms of majority living and working conditions.

China provides an excellent example. China plays a critical role as the final assembly platform for East Asia’s export driven growth. As the Asian Development Bank explains:

“there is the cluster of highly interdependent, open, and vibrant economies in East Asia and Southeast Asia that include the NIEs, the PRC, and the more advanced countries of ASEAN. With the PRC at the center of the assembly process and with exports going mainly to the U.S. and Europe, production in and trade among these economies have been increasingly organized through vertical specialization in networks, with intense trade in parts and components, particularly in the Information, Communication and Technology (ICT) and electrical machinery industries.”

China’s unique position is highlighted by the fact that it is the only country in the region that runs a deficit in components trade, and whose exports are overwhelmingly final products. It is this unique position that has enabled China to increase its share of world exports of ICT products (such as computers and telecom equipment) from 3 per cent in 1992 to 24 per cent 2006, and its share of electrical goods such as semiconductors and semiconductor devices) from 4 per cent to 21 per cent over the same period. Of course, these are not truly Chinese exports, but rather exports assembled/produced in China. Foreign corporations are responsible for approximately 60 per cent of all Chinese exports; their share is 88 per cent for high-tech goods.

All this production has generated real wealth for some Chinese. As the BCG study highlights, China now hosts the third greatest number of millionaires and is closing fast on Japan for the number two position. But what is happening to the manufacturing workers in China that produce the goods consumed by people in other countries?

Loss of Jobs Globally

Perhaps most surprising, according to a new study by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the actual number of manufacturing workers in China is on the decline. That’s right. China is not stealing jobs from anyone. The globalization process is erasing jobs everywhere, including in China, the “world’s workshop.”

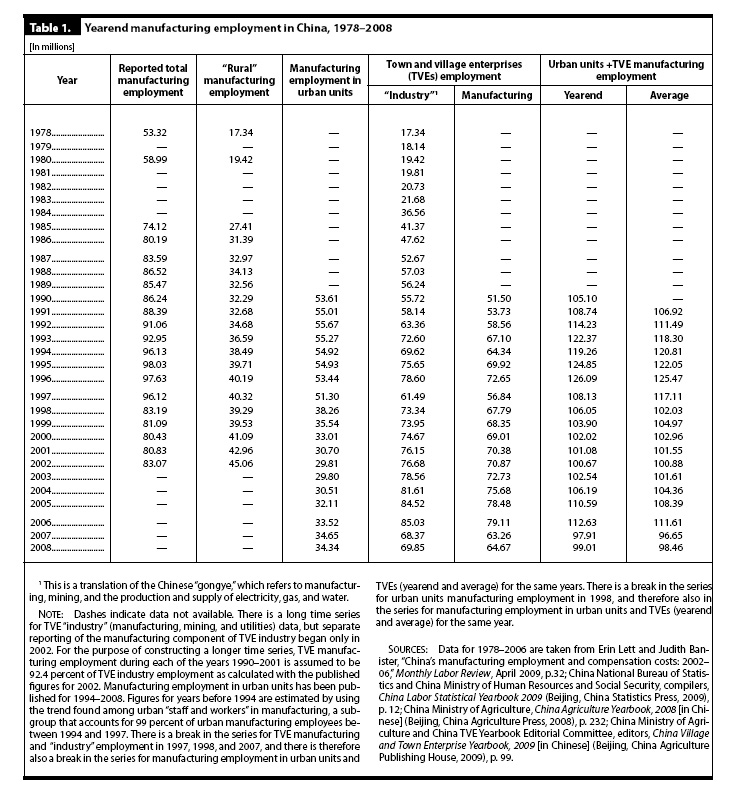

The BLS drew upon official Chinese statistics to create a consistent employment series. They found that the sum of manufacturing employment in urban enterprises and manufacturing employment in township and village enterprises (TVEs) provided the best estimate for the total number of Chinese manufacturing workers. As the last two columns of table 1 below show, the absolute number of manufacturing workers in China has declined from a peak of 126.09 million in 1996 to 112.63 million in 2006. The total drops even more dramatically in the following two years but that is largely because the Chinese government decided to drop self-employed workers from the TVE manufacturing employment series beginning in 2007.

Thus, despite becoming the workshop of the world, there has been no increase in the total number of Chinese workers employed in manufacturing. That means the enormous increase in manufacturing production has been underpinned by an increase in the capital intensity of production and, perhaps even more importantly, a significant increase in the pace of work and length of the work week. In terms of the latter, the BLS reports that some 25 per cent of urban manufacturing workers were on the job between 41-48 hours a week and 35 per cent worked more than 48 hours a week. Work hours are generally longer in the TVEs. No wonder that we have seen a dramatic increase in labour struggles in China.

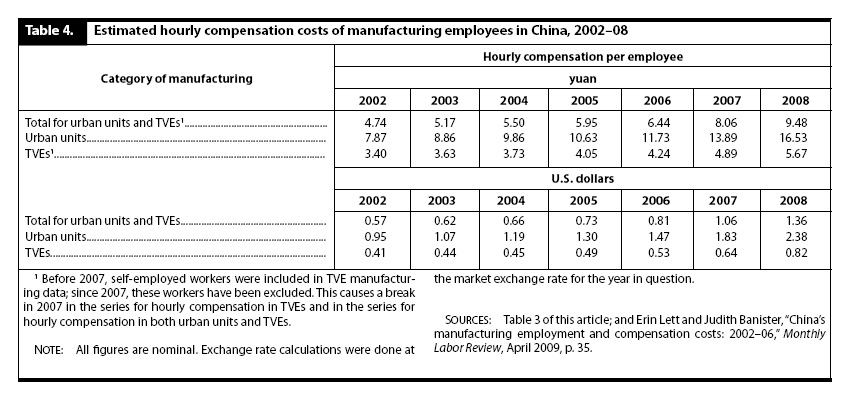

The BLS also estimated the hourly compensation of Chinese manufacturing workers. It is worth emphasizing that the figures in the table 4 below represent compensation, which means wages plus all social benefits. Moreover, they are in nominal terms, which means that they are not adjusted for inflation. This is critical because inflation in China has been substantial. Some researches believe that Chinese workers suffered a decade of wage stagnation until 2002. That means that the nominal compensation increases shown in the table below may well reflect both wage catch-up and higher costs for an unchanged package of social benefits.

The BLS also estimated the hourly compensation of Chinese manufacturing workers. It is worth emphasizing that the figures in the table 4 below represent compensation, which means wages plus all social benefits. Moreover, they are in nominal terms, which means that they are not adjusted for inflation. This is critical because inflation in China has been substantial. Some researches believe that Chinese workers suffered a decade of wage stagnation until 2002. That means that the nominal compensation increases shown in the table below may well reflect both wage catch-up and higher costs for an unchanged package of social benefits.

As the table shows, after several years of significant gains, Chinese manufacturing workers now earn an average of only $1.36 per hour. In relative terms, Chinese hourly labour compensation costs in 2008 are roughly 4 per cent of those in the United States. They even remain considerably below those in Mexico.

What is especially significant about the above is that China is the world’s star economic performer. If Chinese workers are finding their manufacturing jobs disappearing and their compensation limited, no wonder that workers in other countries are facing serious challenges.

What is especially significant about the above is that China is the world’s star economic performer. If Chinese workers are finding their manufacturing jobs disappearing and their compensation limited, no wonder that workers in other countries are facing serious challenges.

We don’t have a broken system. Rather we have a system that works very efficiently to enrich an ever smaller number of people. Those people think that it is working just fine. •