Tahrir Square: This is What Democracy Looks Like!

“The more late his decision to go away is, the more creative and more beautiful the revolution. So I want him to give us some more time to make a more beautiful revolution.”

— pro-democracy protester in Tahrir Square, Ali El Mashad.

Since the Egyptian revolution’s first mass protests exploded throughout the country on January 25th, many so-called pundits and analysts have frantically struggled to find a suitable historical parallel in order to make sense of the situation to the outside world: France 1789; Iran 1979; and Tiananmen Square 1989 are just a few of the many analogies that have dominated popular discourse in the West. Meanwhile, the U.S. government and its allies have predictably continued to emphasize familiar concerns over ‘stability’ and ‘order,’ the broader regional implications for neighboring Israel, and the specter of an ‘Islamist’ takeover. But it hardly matters to any of these foreign players, of course, that in the end the people of Tahrir Square and all across Egypt do not seem to be thinking about any of these concerns at all, nor do they particularly care about any ongoing speculation surfacing from outside of the country at the moment.

For the first time ever, perhaps, Egyptians have seen a genuine opportunity for freedom and refused to let it go, boldly defying a brutal and seemingly immovable thirty-year-old dictatorship and commencing to build in its place the foundation of a grassroots democracy that only continues to grow stronger every day. A new and vibrant democracy is being born in Egypt today against all odds, evolving live in front of a captured global audience in a way quite unlike ever before. The Egyptian revolution has to this point flourished as a truly non-violent, inclusive, and participatory democracy – and, most importantly, managed to do so without any appointed leaders, dominant ideologies, or easy slogans, except to say simply that the dictator must go.

The all important ‘fear barrier’ has been decisively shattered and shows no sign of returning any time soon.

What final character the Egyptian revolution will ultimately take as of now remains unclear, but whatever happens, what will follow is at its core of less importance than what Egyptians have already managed to achieve.

All We Need Is Time…

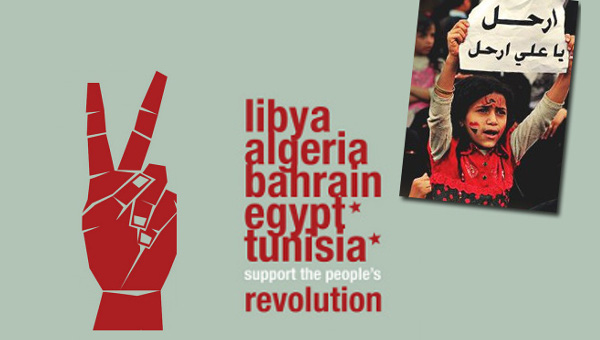

The Middle East has long been considered among the least likely places in the world to produce anything like a popular revolution. Arabs in particular are conventionally characterized as politically weak, apathetic, and most recently ‘not ready’ for democracy. When the people of the ‘Arab World’ finally do rise up en masse – as they have done not only in Egypt, but Tunisia, Yemen, Jordan, and beyond – they are met in the West only with fear and anxiety over the coming ‘chaos.’

Yet despite all the familiar rhetoric, it is not the imagined ‘Islamist’ threat that troubles the West most but the actual threat of a good example – in other words, exactly the type of grassroots democracy that has flourished in Tahrir Square. Indeed, it was in the interests of the Western-backed dictatorship all along for President Hosni Mubarak to cede power as quickly as possible in order to not only pave the way for a guided transition to ‘democracy’ but also fatally undercut the revolutionary protest movement in its most embryonic stage in the process. Paradoxically, the longer Mubarak stayed in power, the more radical and unified the Egyptian revolution increasingly became.

The foremost concern on everyone’s mind now seems to be: will the Egyptian revolution descend further into ‘chaos’ or end peacefully in ‘democracy’? Egyptians have joined together to answer that question by showing the world a living example of democracy in action beyond what many of us even imagined possible. Far from simply ceding power, Mubarak has already given the protest movement more than they could ever hope for: time to actually find democracy, and build it anew.

Meet Me in Liberation Square

Tahrir Square has served as the epicenter of the Egyptian revolution since January 25th, playing out as the symbolic battleground for the future of Egypt itself. Indeed, it has by now grown beyond much more than a mere symbol, eventually taking on the appearance of a permanent communal settlement of fully fitted tents and even at a point coming to be commonly referred to as a ‘liberated zone’ and the ‘Republic of Tahrir.’ What Egyptians have done in Tahrir Square is truly remarkable: they have made it their home, social space, and political arena – all in one. Over the course of two weeks, Tahrir Square has not only proven itself to be the primary site where the Egyptian revolution must be definitively won or lost but, above all, actually provided a 21st century model democracy from inside the hollowed shell of the ancien regime – fully outside the narrow proscriptions of state power.

Make no mistake, the Egyptian revolution was never at any point a war of attrition; the longer Mubarak stalled, the longer he only prolonged the inevitable. Ordinary Egyptians critically never stopped mobilizing in the streets of Cairo and other major cities across the country until sign of victory, only growing more defiant, steadfast, and united by the day. The revolutionary example of Tahrir Square quickly spread to take the form of workplace strikes, mass protests outside the presidential palace, and ultimately an occupation of the parliament building (officially known as the ‘Peoples Assembly,’ and, at that moment, finally worthy of the title).

Indeed, the familiar rhetoric in the West – faithfully echoed all along by Mubarak and his cronies – about Egypt ‘not being ready’ for democracy is not only clearly indicative of a dated Orientalist paradigm that is rife with hypocrisy, but it is also by now a moot point: beyond simply ready for ‘democracy,’ Egyptians have demonstrated before the eyes of the world a living model of everything it should – and can – still be. Tahrir square has seen an outpouring of creative street art, music, and poetry; everything from weddings to funerals, prayer to play – the full spectrum of human experience.

Democracy in Action

But Tahrir Square represents much more than a modern-day ‘carnival of the oppressed’: Egyptians of all social strata have voluntarily taken to street cleaning; directing midday traffic; coordinating neighboring patrols amidst early outbreaks of looting; and even organizing self-defense committees during the sporadic February 2nd clashes with the baltagiyya (thugs), fully equipped with security checkpoints, look-out posts, and makeshift hospitals to treat the wounded. The poorest Egyptians comprising the informal sector and surviving on less than $2 a day have thrived like rarely before, selling everything from Egyptian flags to newspapers. Price inflation under these conditions remarkably has not soared, and where price has been at all an issue people have not hesitated to share or willingly give away for free what little they possess in the way of food or drink.

Overcoming a long legacy of mutual hostility and suspicion along traditional sectarian lines, there is an Egypt for everyone in Tahrir Square: men and women, young and old, Muslim and Christian. Lively and vigorous debate – free and full of meaning, for once – have filled all four corners of Tahrir Square, conveying by loudspeaker the full array of diverse political views and opinions present. Any formal adoption of proposals has been decided democratically by clear majority-vote based on the overall share of ‘cheers’ or ‘boos’ coming from the crowd at large.

Contrary to popular belief in the West, the Egyptian revolution has not been one of ‘chaos’ but rather the complete opposite. Against the backdrop of a brutal and repressive dictatorship of thirty years, the people of Tahrir Square have in a few short weeks cultivated a new set of social relations in Egypt based broadly on the principles of solidarity, equality, and common cause – totally subverting the prevailing order in which people play only a dominant or subordinate role under a rigidly codified social hierarchy. In reality, the Egyptian revolution that has emerged in the heart of Tahrir Square since January 25th already far and away surpasses as an alternative, by any standard measure, not only the dictatorship in Egypt but anything even remotely being passed off as ‘democracy’ here in the West.

Rather than Egypt looking for a suitable democratic model in the West, it is, contrarily, the West and others who should be looking to find it in Egypt’s Tahrir Square.

People Power 2.0

The Egyptian revolution has been largely perceived as a ‘leaderless’ phenomenon, consisting of a loose and informal coalition (or ‘network’) of disenfranchised youth, radical online activists, and organized labour unions. Yet no protest movement in history arises out of nothing; it has been the inevitable result of persistent grassroots organization (both online and offline) that only awaited a moment of mass consciousness to finally come to fruition. In reality, the Egyptian revolution can just as easily be characterized as comprising many leaders, who have emerged more or less spontaneously in direct response to changing circumstances on the ground as they arise. To whatever extent it has by necessity existed, leadership has been at once diffuse and organically rooted within the protest movement itself.

The basic reality on the ground, however, has not prevented both Western and foreign media from conspiring together to single out a few likely candidates to play the role of ‘charismatic leader’ and give this collective, largely spontaneous revolt a unifying face – first with Mohamed ElBaradei who, for all his merits, has been largely aloof from dynamics of the mass protests on the ground, and may also be too old to appeal to his overall demographic base; and now, most notably, Wael Ghonim, the Google executive whose emotionally powerful interview on Egyptian television immediately following his release from prison helped invigorate the protest movement during a momentary period of uncertainty.

Yet the key strength of the Egyptian revolution to date has been its overwhelmingly popular appeal, which has dynamically cut across all sectors of society. Ironically enough, it has succeeded to whatever extent it has not in spite of a lack of formal leadership but exactly because of it. The ‘leaderless’ online networking channels provided by social media have dynamically transformed into a concrete example of democracy in action in Tahrir Square – one based crucially on a unique combination of individual agency and collective will, not simply the confidence of a specific leader to tell them what to do or direction to take.

The Muslim Brotherhood was notably not a central player during the early phase of the Egyptian revolution because, like any traditional organization, it was out of touch with not only the diversity of political views and opinions in the streets but also the Internet technology through which the first mass protests were in large part originally mobilized. Indeed, the very concept of the ‘leaderless,’ collaborative, and decentralized organizing structure evolving on the ground remains wholly foreign to them. In other words, they did not simply fail to participate in the early mass protests, they were left behind.

The Muslim Brotherhood’s declining political relevance became most obvious when it agreed to enter negotiations with a regime already long rejected and devoid of all legitimacy in the streets. These negotiations only further confirmed the growing overall disconnect between the Muslim Brotherhood’s leadership and the masses in the streets, offering the embattled dictatorship a new lifeline in the process (albeit a short-lived one). Whereas the people of Tahrir Square have been able to transmit key information and convey any demands instantly and constantly via social media, ‘opposition groups’ and the dictatorship itself have only managed to enter into the dialogue at least two days out of step with popular opinion on the ground.

Taking Back the Idea of Democracy

The Egyptian revolution was built en masse, by the majority of Egyptians together. Why would a people embarking on a shared social project, with so much collectively at stake, in any way voluntarily alienate ownership over the process as it develops to somebody else? And anyway, which any one leader or group of leaders alone could aim to capture the full range of views and opinions of all the people in Tahrir Square and across Egypt? Who else but themselves? The people of Tahrir Square actually held a vote at one point about whether or not to elect representatives to make key executive decisions on behalf of the protest movement; they overwhelmingly and decisively voted ‘no.’ Under such circumstances, it is entirely natural to welcome with suspicion any formal leadership or representation – particularly when the only kind you have known for the duration of your lifetime has been thoroughly corrupt, democratically unaccountable, and morally bankrupt.

A protest movement can only be called such to the extent that all its members feel a shared sense of belonging and ownership – one that can only emerge organically out of a core set of common grievances and joint struggle, not any single identifiable leader or narrowly defined party platform. What is at issue at present is not a lack of leadership or organizational structure, but, more precisely, what type is it exactly that will emerge, how will it organically take shape, and in whose overall interests will it operate? The obsessive search for leadership is trying to solve a problem or fill a void that in reality does not exist in the first place.

But leadership is not in any way distinguishable to us, after all, until it comfortably conforms to conventional wisdom; all other alien forms that fall outside this purview are simply not recognizable, much less legitimate. Fortunately, the Egyptian revolution has consistently aspired to defy convention. What is, after all, the purpose of revolution if not to at once disrupt dominant social norms and transform them anew? Indeed, a new sense of agency has emerged among the majority of Egyptians – the kind that can only take root when the very idea of state authority loses any remaining trace of legitimacy and finally collapses.

Regardless of whatever happens now, the single truth remains: whatever the dictatorship finally concedes after thirty years of rule will fall short of what Egyptians themselves have already built in a few short weeks

“Muslim, Christian, We Are All Egyptian!”

What has been perhaps most incredible about the Egyptian revolution overall is its general lack of sectarianism and internal division (save, of course, for the baltagiyya and relatively small proportion of Mubarak loyalists). Indeed, Egyptian society is far from homogeneous but still politically and economically far less stratified than other countries in the region. The majority of Egyptians have known to a more or less comparable degree the same political repression and economic hardship while living under dictatorship, resulting in a general identification with the same core grievances across all strata of society: poverty and unemployment, rising basic commodity prices, and government corruption top among them. The Egyptian revolution depends in large part on this shared sense of systemic injustice.

Amidst the fundamentally false choice being perpetuated in the mainstream media between a Western-backed dictatorship and an ‘Islamist’ takeover, Egyptians have instead chosen to ‘vote with their feet’ and resoundingly reject both. The Egyptian revolution will not only finally bring about liberation but hopefully, once and for all, end a long legacy of sectarian division between Muslims and Christians – one in which the dictatorship has been the only clear and constant beneficiary. The Egyptian revolution in the end must reach far beyond the narrow interests of any one particular interest group or another but unite all around the project of building a new Egypt where everyone has a place, based critically on the new transformative set of social relations that have flourished in Tahrir Square.

Reform Versus Revolution

Egyptians will be particularly keen now on not allowing the military ‘caretaker government’ to merely implement cosmetic democratic reforms along the lines of the 1919 and 1952 revolutions, fundamentally preserving the dominant power structure that has ruled the country uninterrupted for over half a century. A more golden opportunity for genuine social change may not arrive again soon, if ever, and the majority of Egyptians know it. If they do not follow through fully with the revolution that is now underway, they risk it being co-opted right from underneath them – not by ‘Islamists,’ as feared in the West, but by the very same regime they have fought for eighteen extraordinary days to overturn.

So long as the basic dominant power structure remains intact, there can be no truly viable, sustainable, and meaningful transition to democracy. The people of Tahrir Square know this fact only too well, which is why they have until now refused to compromise and allow this revolutionary moment to be stolen from them. Democracy can be many things to many different people, but what democratic foundation is set in place will be paramount. Here the Egyptians have an opportunity, a luxury to some degree, that here in the West we simply do not enjoy as our dominant institutions and overall centers of power appear, more or less, permanently fixed in our imagination. Egyptians have the all important advantage of starting anew, whereas we are far too constrained by the liberal democratic system already in place to envision anything that will drastically break ranks with the prevailing social order. While the idea of liberal democracy may have some purchase in Egypt now, once in place it will be infinitely more difficult to imagine an alternative – much less continue to build one.

Key Challenges Looking Forward

Indeed, a crisis or revolutionary moment can unite people in truly spectacular, albeit unpredictable, ways. The test for Egyptians will be not to preoccupy themselves so much with the difficult question of what exactly lies ahead so as to lose sight of what they have already built. It would truly be a shame to see Tahrir Square’s burgeoning democracy lost for no other reason than the interests of ‘stability’ and ‘order’ (especially when only code for the prevailing status quo antes). After all, it is exactly the ‘stability’ and ‘order’ of the past thirty years – with open Western complicity – that got Egyptians here in the first place and whose crushing effects they have fought for their lives to change, led all along by the country’s youth who no doubt have the most to lose. What is ‘stability’ and ‘order’ in the end without “democracy, bread, and dignity,” the popular rallying cry of the Egyptian revolution? Ironically enough, calls for ‘stability’ and ‘order’ have always come loudest from either outside of the country or on high, never, crucially, from those in the streets.

Beyond all the focus on ‘stability’ and ‘order,’ foreign relations with Israel, and the fear of ‘Islamists’ taking power, the key challenge ahead is how Egyptians will be able to both defend and, more importantly, advance what they have now started. Egyptians have clearly coalesced around a core set of concrete, coherent, and non-negotiable demands that will lay the basis of whatever civilian government is likely to follow; however, the depth and permanence of the Egyptian revolution will be measured in exact proportion to how the people of Tahrir Square now will relate to one another once those basic demands are met in full and the jubilation and euphoria that originally punctuated Mubarak’s ouster finally dies away.

Once a sense of normalcy begins to return to the country, and calls for basic ‘stability’ and ‘order’ begin to hold sway even within the ranks of the protest movement itself is exactly when the Egyptian revolution’s longterm potential of survival will be tested most. After all, it is always easy to unite around what you stand against but altogether another matter to remain united long enough to achieve what you actually stand for, particularly when economic hardship returns to the country and food prices begin to dramatically rise – all the underlying systemic causes of the Egyptian revolution in the first place. Furthermore, whatever new government finally emerges will not only have the difficult task of filling a large, empty power vacuum but also inheriting the hallowed remains of a functionally ‘failed state.’

As Egyptians enter the yet unclear transition from dictatorship to the first ever free and fair elections in the country’s history, it is imperative that they not forget what was born in Tahrir Square where democracy has been all along. Indeed, Tahrir Square should not be remembered as simply a positive corollary of a larger transitional phase to something else, but rather what we should all aspire for in the first place.

Egyptians are in the process of building the kind of world they want to live in – one that should serve as a basic standard for us all. If you really want to know what democracy looks like, you will find no better example than Tahrir Square. •