Introduction: The Limits of a Good Idea

It started as a good idea. Rather than taking the path of the old Latin American left, in the form of the guerrilla movement, or the Stalinist party, Brazil’s Workers’ Party (Partido dos Trabalhadores, PT), aided by strong union and social movements, decided to try something new. The challenge was to somehow combine the institutions of liberal democracy with popular participation by communities and movements. The answer eventually became participatory budgeting (PB). Introduced in the city of Porto Alegre in 1989, PB was a highly innovative experiment in co-management and de-centralization (Weyh, 2011). It allowed communities of diverse political stripes to democratically manage a small portion of their city’s budget. Not only did this result in more and better services for poor communities, it also opened a space where people could learn new democratic skills and build new solidarities. In PB, a virtuous cycle of democracy was unleashed: the more people participated, the more people learned to participate. Add to this, a number of poverty reducing programs at the national level, such as Bolsa Familia, and you suddenly had a new path to social transformation: peaceful, gradual and pluralist.

It wasn’t long after the PT acquired power at the national level in 2003 that cracks in its political economic model began to show, however. Agrarian reform, the key demand of one of its most important early allies, the Brazilian Landless Workers’ Movement (MST), was effectively dropped from the PT’s program. More accurately, the PT re-articulated the MST’s demand of agrarian reform by strengthening the productive capacities of existing MST lands, rather than addressing Brazil’s highly unequal land ownership structure, in which the top 1 per cent own 50 per cent of the land. In other words, of the three key elements of the MST’s program, namely “occupy, resist, produce,” the PT opted to act only on the last point. It did so by, for example, opening avenues for the sale of products produced by MST run cooperatives, as in the case of Cooperdotchi, an agricultural cooperative in the state of Santa Catarina. This re-articulation of the MST’s goals has created ongoing conflict between the government and the MST who has itself re-articulated its demand for agrarian reform as, “food sovereignty,” focusing instead on the government’s alliance with agribusiness (Ferrero, 2012).

Anti-FIFA World Cup Sentiment

The other traditional ally of the PT is the middle class (particularly in the southern states), who have benefited from strong growth and employment in recent years. However, health and education have been badly neglected, and sections of the middle class are feeling the effects. This comes at a time when the government is spending billions of dollars on the FIFA World Cup (in 2014). This situation has created a growing cynicism among people expressed in the popular phrase, “imagina na copa” (imagine during the cup!). First heard in middle class circles, the expression is a criticism of problems in transportation, health care or any situation in which there is delays, line ups or disorganization. The expression soon became more generalized, as people began to perceive the world cup as the source of the country’s growing problems. In other words, if its this bad now, “imagine during the cup!”

Unions, another traditional bastion of PT support, have also gone on board with this anti-cup sentiment, several of them threatening strike actions during the tournament next year if their demands are not met now. In addition, indigenous groups are facing displacement around the country, as new stadiums and infrastructure is built. For example, in March of this year, an indigenous community was forcibly evicted from an abandoned museum next to the Maracanã, Brazil’s most emblematic soccer stadium located in Rio de Janeiro, which recently underwent a $500-million renovation. Poor communities living in favelas (shanty towns), many of them new supporters of the PT, have also faced similar displacement.

Many people have also grown frustrated with the PT’s “strategic alliances” with the right, for example, its decision to allow Marco Feliciano to be the chair of Brazil’s Human Rights Commission. To the outrage of the LGBTQ community (and progressive sectors more generally), Feliciano recently led an initiative that encourages gay people to undergo psychological treatment. In short, a variety of sectors supportive of the PT have real reasons for being dissatisfied with the government’s handling of, not only the World Cup, but a number of other issues also. It seems the PT’s model of a new left was reaching its limits.

“Não me representa”

The protests have their most immediate roots in Porto Alegre, and indeed it is here that the contradictions of the PT’s model are most evident. To the surprise of many, Porto Alegre elected a right wing government in 2004, that is, after 16 consecutive years of PT rule. This was a huge blow to the party in the city that hosted the World Social Forum no less than five times. Some even began to see the PT as having reached a crisis. After a few years of relative quiet, middle class students began to organize against the privatization of public spaces in the city center, as part of preparations for the World Cup. Parallel to this, in 2011, the Comitê Popular da Copa (World Cup Popular Committee) was formed, composed of several groups including the MST. Their goal was to raise awareness and begin organizing against the cup and what they saw as the Municipal government’s mistaken priorities.

Since 2004, Participatory Budgeting, the PT’s signature program, has been noticeably weakened. For example, by June of 2012, only 17 per cent of the money allotted that year to various programs through the city’s PB had actually been spent (De Olho). Meanwhile, participation has decreased in recent years. In addition, poor communities near one of the local soccer stadiums, Arena Grêmio, were displaced in preparation for the cup. Lastly, there has been a growing discontent about the city’s public transportation, resulting in successful mobilizations in April 2013, which managed to stop a 20 cent hike in transit fares. From here, the movement took root in São Paulo, where it grew quickly and became strengthened by the participation of the Subway Workers Union who were already struggling for a new contract (Costa, 2013). The transit movement is led by Movimento Passe Livre (Free Fare Movement), or MPL. Formed in 2004, the MPL considers itself a horizontal, autonomous, and non-partisan movement. Importantly, although non-partisan, the MPL does not consider itself anti-party. Their demand of free public transit has resonated throughout the country, posing direct challenge to Brazil’s oligopolistic transit system (Gibb, 2013).

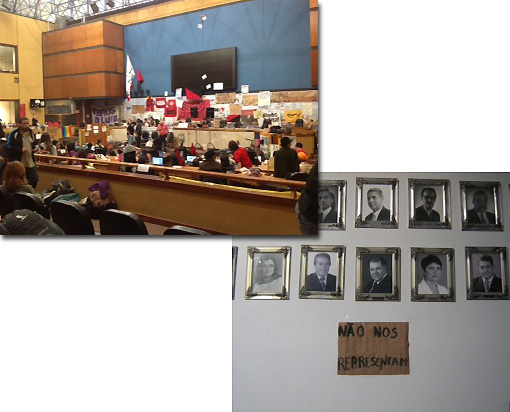

The magnitude of the mobilizations caught the PT totally by surprise. Indeed, during the first large demonstrations on June 17, there was no visible PT presence in Porto Alegre. The demonstration was organized by Bloco de Luta Pelo Transporte Público (Struggle Block for Free Transit), a popular front bringing together several organizations, and greatly amplified via social media networks. About five to seven thousand people amassed at the city’s prefecture. The mood was confident, energetic and inspiring. Youth between 15-25 years of age were the majority. People freely experimented with various chants, including, “sem partido” (without a party), “Não nos representam” (doesn’t represent us), “Brasil acordo” (Brazil woke up), “acabou o amor, Brasil vai virar Turquia,” (the love is over, Brazil will turn into Turkey), “vem pra rua” (come to the streets), and “sem violencia” (without violence).

Some people held Brazilian flags with the words, “primaveira brasilera” written on them, while others held up Turkish flags. Clearly, in addition to the national context, protestors had similar global revolts in mind. Finally, placards demanded better public education, health care and an end to the World Cup. Interestingly, despite the anti party sentiment, party flags were in plain view, including those of the Socialism and Freedom Party (Partido Socialismo e Liberdade, PSOL), a socialist party to the left of the PT. As with all subsequent demonstrations, protestors were met with police repression, which included the use of teargas and rubber bullets.

Some have noted that the demonstrations contain right wing and even fascist elements (particularly in the bigger cities), citing examples of vandalism and violence against left wing parties. However, it would be very premature to say that these elements are becoming a social force. For example, in Porto Alegre, violent groups are a tiny minority and there were no reports of organized fascist activities. It is true that in some of the bigger cities attacks on left wing parties have been reported, but at least some of these can be attributed to individuals or small groups that simply reject the presence of any parties on the streets.

It is true that a simplistic rejection of all parties can lead to an apolitical nihilism, which indeed formed part of the sentiment right before the 1964 Brazilian dictatorship. However, we must not immediately equate an anti-party sentiment with right wing politics, as some have done. It is also worth noting who is making the claims of this being a right wing movement, namely the PT (at least certain currents within it) and the corporate media, supposed bitter enemies. They each have their own reasons, however. Given that the movement contains anti-party elements (and therefore is not pro-PT), the PT’s thinking is, “if they are not with us, then they must be right wing.” For its part, the corporate media’s strategy has been spinning the movement as being simply anti-corruption and anti-taxes so as to impose its own right wing agenda and create the conditions for replacing the PT.

The next demonstration took place on June 20, only this time it brought together close to 10,000 people, that is, despite persistent heavy rain. Overall, over a million people took to the streets in over 100 cities that night. Unions had a significant presence for the first time in Porto Alegre, including members of SIMPA, representing the city’s municipal workers. Also of note is that this time, few if any party flags were in view. This was also the case during the following demonstrations on June 24th and 27th. However, gone were also the anti-party chants. Interviews revealed that by now the movement had recognized the co-optation attempts by the right wing media, and dropped its simplistic anti-party position. Indeed, they recognized that a number of parties had been on the ground floor of organizing. For example, Lucas Monteiro, an important figure in the free transit movement in Porto Alegre, is also a member of PSOL.

The movement’s rapid learning was evident at a student assembly held at Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS) on June 27th, where activists from a variety of groups, including the MPL, suggested that the way forward was to develop a coherent political program. In addition, at the demonstration later that night, a mysterious plane or helicopter was flown over the protestors, projecting a number of political messages, including “sem partido.” The crowds responded with what, up to this point, most accurately captures their political sentiment: “não nos representam” (doesn’t represent us). In other words, in a matter of days, protestors had transformed a simplistic “sem partido” to “não nos representam,” therefore avoiding co-optation by the right while asserting their commitment to direct political participation.

Beyond the Workers’ Party?

After the PT’s initial surprise, it reacted by trying to sympathize with the protestors. Brazilian president, Dilma Rousseff, stated that the protests were a sign of Brazil’s democratic strength and that the government was ready to listen to the streets. In addition, more than 20 municipalities accepted a 20 cent reduction in transit fares. Nevertheless, in preparation for the next demonstrations, Dilma quickly deployed the military to several major cities. Former president Lula perhaps best encapsulated the PT’s position, stating that the movement should now channel its demands to the negotiating table. Indeed, Dilma invited Free Fare Movement (MPL) leaders to a meeting in order to find a solution. This resulted in a number of proposals by the government, with the two most important ones being: a popular plebiscite for a constitutional reform, and a public transportation plan with $25-billion of new funding. In addition, Tarso Genro (PT), governor of Rio Grande do Sul, announced free transit for students in the state. These are major victories for the movement.

If carried through, these proposals demonstrate the PT’s ability to incorporate some of the protestor’s grievances into the PT model. However, it is clear that it can’t incorporate others. For example, consider one of Dilma’s recent statements regarding the protests: “The streets are telling us that the country wants quality public services, more effective measures to combat corruption … and responsive political representation.” Yet, for better or worse, what the protestors want is not “responsive political representation.” Indeed, one of the central themes of the movement (maybe even the central theme) is people’s deep suspicion of political representation. Direct democracy, at least as much as free transit or quality education, is what this movement stands for. The question now is whether the PT’s re-articulation of the movement’s demands will placate the streets.

However, this seems unlikely at the moment. Several unions, including the Central Única dos Trabalhadores (CUT), Brazil’s most important union federation, called for a general strike to take place on July 11, and their demands included quality public transportation new investments in health and education, and agrarian reform, hardly traditional union demands. In Porto Alegre, Bloco de Luta organized a popular assembly that brought together over 300 activists. Several bold and innovative proposals were discussed, such as organizing a permanent encampment in the city. One woman demanded transit companies’ books be opened so that, to paraphrase, we find out how much money is going to workers, and how much is being spent by the owners on champagne. Several union members were in attendance, including the leadership of SIMPA who pledged full support for the movement. In their general membership meeting later that week, the union approved full participation in the upcoming general strike. Lastly, the MST is also pledging full support for the movement, now calling for agrarian and urban reform.

A recent poll of Brazilian voters shows Dilma’s ratings have dropped from 57 per cent to 30 per cent, while 81 per cent say they support the protests (Guardian). Nevertheless, it is certainly too early to say how far this movement has weakened the PT hegemony in the country. It has, however, exposed its weaknesses and limits. More than this, by emphasizing the centrality of direct political participation and active struggle, the demonstrations are also posing a tentative alternative to the PT model for social transformation. Although Participatory Budgeting, the PT’s definitive political initiative, does provide important avenues for democratic learning, so do the streets. As one demonstrator’s placard read, “Essa é nossa educação!” (this is our school!).

However, as Le Monde reports, for 70 per cent of the youth on the streets, these protests were their first (Bava). Hence, as Emir Sadr notes, this is a young movement that lacks clear goals for the future. As such, it can also create a new space for the right, as we have seen in the “Arab Spring” and in the case of Spain (something PT supporters like to point out). This should not deter us from fully supporting this movement, though. As Rosa Luxemburg put it, “the errors committed by a truly revolutionary movement are infinitely more fruitful than the infallibility of the cleverest Central Committee.” Regardless of where the movement goes from here, it has already shown the world that its capable of big victories.

Post Script: Historic General Strike

The first since 1991 (and the fourth in Brazil’s history), the general strike that took place on July 11, 2013 successfully brought much of the country to a standstill. The strike came amidst, not only widespread popular protests, but also an upswing of strike activity that began in 2008. This culminated in a yearly average of 560 strikes by 2012, a record since 1998 (Le Monde). The strike also took place a day after the national chamber of deputies rejected Dilma Rousseff’s proposal of a popular plebiscite for political reforms, opting instead to form a “working table” to discuss the issue in the future. Unlike previous general strikes, this one brought together workers and social movements. Diverse actions were witnessed throughout the country, including road blockades, building occupations, demonstrations and marches.

Porto Alegre was one of the city’s most affected by the strike. The public transportation system was almost completely paralyzed and practically all businesses were closed, giving the city the feel of a national holiday. The strike actually began on the night of July 10th in Porto Alegre, as a number of activist groups occupied the municipal chamber of aldermen demanding “free transit now” and the opening of transit companies’ books. The next day, hundreds of workers gathered in several spots throughout the city and marched toward the city center. In the early afternoon, Bloco de Luta, asked the unions to continue their march all the way to the Chamber, where the occupation was ongoing. This revealed a certain disorganization in the movement, as many activists were left wondering where exactly to meet and march toward.

Once under way, the march split downtown, with about 3000 people continuing to the Chamber and 2000 remaining near the prefecture. Surprisingly, these numbers were a bit lower than in previous marches and demonstrations. Although organized workers were much more visible than in previous days, it seems most decided to stay home rather than go out to the streets. Also more visible were party flags, demonstrating that the anti-party sentiment of the first wave of demonstrations had considerably eroded. Now it’s June 12, 2013, and things are back to “normal” … at least for now. •