São Paulo has some of the worst traffic in the world. Workers’ daily commutes can be over two hours – one way – without ever leaving the city. Rain or traffic accidents can easily increase a commute to over four hours. Streets become so congested during peak hours of traffic that the local news stations report on the length of kilometers of stopped cars and trucks on the highways entering the city. There are permanent signs mounted beside these highways with lights that can be turned on and off indicating that “traffic is stopped in front.” São Paulo has the highest per capita density of private helicopters in the world. Those with serious money in this extremely rich and unequal city choose the option to literally fly over the traffic jams.

People traffic can be equally awful. Despite an extensive underground metro and many bus lines (with 60km of dedicated lanes, diesel, bio diesel, and electrified buses, double and even triple length articulated buses) in São Paulo, buses and subways fill to the point of internal pressure. Line ups to get on the subway can be as long as two hours while buses that are filled beyond capacity roar past line-ups of passengers standing at the bus stop.

People traffic can be equally awful. Despite an extensive underground metro and many bus lines (with 60km of dedicated lanes, diesel, bio diesel, and electrified buses, double and even triple length articulated buses) in São Paulo, buses and subways fill to the point of internal pressure. Line ups to get on the subway can be as long as two hours while buses that are filled beyond capacity roar past line-ups of passengers standing at the bus stop.

The buses in São Paulo are painted with different colour schemes. The various colours seem like they are designed to help distinguish one bus line from another or bus lines in different parts of the city from each other. In a city the size of São Paulo (population of almost 20 million people), this would help. The colours of the buses are indeed designed to make them distinguishable from others, but the main purpose is to indicate the brand of the bus. There is no “public” transit system. There is “collective transport” because it’s run by private, for profit companies that combine to maintain oligopolistic control over the “market” for transport routes. Critics refer to the companies collectively as a cartel. The system was thoroughly privatized throughout Brazil by Fernando Henrique Cardoso (Brazilian president prior to Lula). Many Brazilians that ride the bus and metro every day don’t know that their system is an important source of (subsidized) profit.

Protesting Transit Fare Increases

The current explosion of protest began with a simultaneous increase in transit fares from 3Rs to 3.20Rs (or more) in cities throughout Brazil. Fares are controlled at the municipal level and are a result of intense negotiations with the private companies. Despite the decentralized nature of the negotiations, fares are typically raised in similar proportions in coordinated fashion, once per year. More than 100 cities have seen a consistently growing number of people taking over streets, highways and even the airports of São Paulo. The brutal and violent response of the Military Police has provoked a wider group to leave their houses and workplaces to join the demonstrations.

One of the key organizers of the demonstrations has been the Movimento Passe Livre (MPL) or “Free Pass Movement.” They originally demanded an immediate revocation of the fare increase. The MPL call themselves a Brazilian social movement fighting for a genuinely public transportation system. A system that has universal access and brings the system back into the public sector. They are similar to movements in Toronto and other cities which use community organizing and demonstrations as tactics to build support and awareness of the crucial role of public transit. They do not contest political power and maintain a decentralized network organizing model.

According to the MPL, organizers started to build the current iteration of the movement for public and universal transit in the north-east of the country, in Salvador in 2003. Salvador is the state capital of Bahia. Life in Salvador was seriously disrupted with some streets paralyzed for 10 days due to demonstrations that followed a 2003 increase in transit fares. The following year, another increase in fares led to similar demonstrations and organizing in Fortaleza, another capital in the north-east of Brazil. Organizers from these two cities met at the 5th World Social Forum in Porto Alegre and initiated the MPL. The movement has grown and spread to cities throughout Brazil.

After five days of increasingly intense and disruptive demonstrations, four large and important cities revoked the raise in fares. After 6 days of disruption, both São Paulo and Rio de Jeinero also returned fares to their previous levels. While the governor of the state of São Paulo threatened that the reduction in fares would lead to a “cut in investments in transit infrastructure” as a consequence, this seemed like the victory the movement had been building toward. But the demonstrations continued to build and strengthen and the next day, the streets once again filled with people.

Not Only About Transit

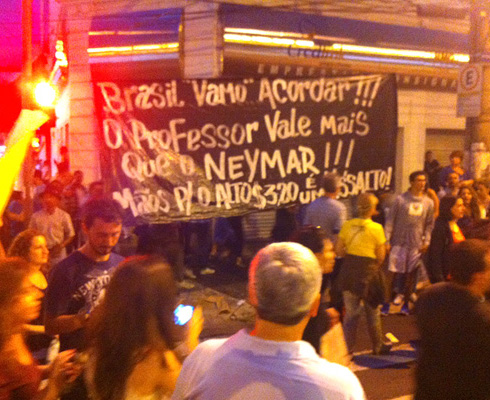

People again took over their city streets throughout the country, this time adding “this was never about only 20 centavos!” to the chants. Somewhat inexplicably for organizers and certainly for the media, the action in the streets was growing and diversifying quickly. The majority of the people massing are young, middle class and mostly white. The constellation of people in the streets differs by city, and is changing every day, but this has largely been the picture throughout the country for the first two weeks of protests. What started with public transit fares has modified and grown to include demands for more public education, health care and security and an end to the extensive, systemic corruption that pervades the political system.

Several critical variables have fortuitously combined to fuel the movement of people into the streets. First, a constitutional ammendment that would severely constrain the ability to criminally charge and prosecute politicians (PEC 37) is currently being debated. Many in the streets are calling it a form of immunity for politicians and are outraged at the prospect.

Second, the federal government (Partido dos Trabalhadores (PT) – Workers’ Party) recently created a permanent commission for human rights. As a concession to opposition politicians, they were forced to allow a right-wing homophobic politician named Marco Filiciano (PSC-SP) as its chair. The first large initiative launched by Filiciano has been to establish a system of (self-referral) psychological assessments and consultations for gay people or people that think they might be gay. It’s referred to as the “gay cure” in the streets. The proposal has obviously been met with strong resistance and disgust in São Paulo – the city with the largest Gay Pride parade in the world – as well as the rest of Brazil. Signs in the streets read – “Filiciano, we haven’t forgotten about you – your turn is coming – we can only deal with one shit at a time.”

Additionally and coincidentally, the Confederations Cup tournament of football – or “warm up” to next year’s World Cup of football (which will also be in Brazil) is currently happening in the recently rebuilt and renovated stadiums throughout the country. Renovations and new construction have cost billions. Demonstrations have strategically and systematically focused on and contrasted the huge investments in football with the basic unmet needs of Brazilians in terms of public health, education and infrastructure. For example, Natal – the site of the brand new Arena das Dunas which cost roughly 400-million Rs doesn’t have a basic municipal sanitation system. Brand new buildings in the local sports complex were knocked to the ground to make way for the new stadium.

Demonstrations have also targeted some of these stadiums during the current Confederations Cup, but Military Police have used every available tactic in their arsenal to keep demonstrations kilometers away from the stadiums. The numbers in the streets have at times exceeded the numbers inside the stadiums. Interestingly, organized fan groups (torcedores) for the national first division clubs in São Paulo have combined to call their members into the streets to participate in the demonstrations. They issued a joint call-out appealing to their members “to fill the streets as if we had won the championship.”

FIFA head Sett Blatter dismissed the demonstrators as opportunists while Aldo Rebelo, federal minister of sport sat beside Blatter at a press conference and proclaimed that demonstrations during the world cup would not be allowed to occur. A commitment that will surely be impossible to fulfill.

What About Organized Labour?

Trade unions and their national labour central (the CUT) have been almost invisible in the streets. This is largely because the movement has declared itself to be unambiguously and aggressively “anti-party” and trade unions are closely associated with the Workers’ Party (PT). Demonstrators have gone as far as surrounding trade unionists, taken their flags, ripped them up and burned them. Several have been beaten. Not two minutes later, the demonstrators surround a young man collecting dead palm leaves on the ground to use as fuel for the fire he’s lighting in the streets chanting “sem violencia / sem vandalismo!” (“no violence / no vandalism”). Various first hand reports have suggested that organized right-wing groups were behind these assaults both in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro.

Anti-PT (and anti-specific PT politicians) and more general anti-political party chants could be heard consistently at demonstrations throughout the country. This is despite strong and unequivocal support from the labour movement for public transit. The current mayor of São Paulo, Fernando Haddad is affiliated with the PT (Workers’ Party). Since taking power, his office has created a structural space for organized groups to regularly meet with the mayor. This includes the labour movement. At the most recent meeting, Vagner Freitas, current president of CUT, clearly stated that the goal in terms of transit was zero fare and that “workers shouldn’t have to pay to go to work.” In spite of this strong and progressive position regarding transit from the top leadership of the labour movement, members and activists wearing colours or carrying flags are taking a serious risk in the streets.

Delicate Moment

The potential of this movement is huge and unprecedented. So are the risks. The direction of the movement is completely open. Diverse and sometimes competing tendencies are visible everywhere. The streets have been more full in the last two weeks than when Brazilians brought an end to military dictatorship in 1985. While “Brazil Wake Up” has become one of the popular slogans on signs in the streets, it has been heavily criticized by veterans of various movements. Much of Brazil was never sleeping. Activists from a wide diversity have been working as they always have been.

Perhaps a large portion of young, middle class Brazil has “woken up.” They are outraged at the lack of public education, health care, public transit as well as physical security in their streets and homes (electric fences, walls capped with broken glass, bars, and armed private security guards are everyday scenery). Signs have appeared in demonstrations calling for a return to military dictatorship. This could be dismissed as minimal or marginal, but the sentiment that “it may be better than a fake democracy because we know what we’re fighting” can’t be easily dismissed. The scene is complicated and contradictory – perfectly representative of Brazilian society.

Veteran trade unionists, community organizers and activists of all backgrounds and affiliations have been as surprised as everyone else in Brazil at the scope and intensity of the current protests. Many had dismissed the MPL as inconsequential. The MPL representatives are currently in direct negotiations with the federal government, including President Dilma Rousseff. The organized left has been simultaneously struggling to collectively analyze what has motivated so many people to take the streets while taking concrete steps to participate and intervene where possible. The organized left has clearly understood what is at stake. The possibility of the movement deepening to include strikes, with many trade unionists advocating and starting to build for a general strike, has combined with relentless pressure from the streets to provoke a response from the federal government.

President Dilma recently announced a series of five interrelated “agreements” or “pacts” to the benefit of Brazil. These include “fiscal responsibility” aimed at limiting inflation and stabilizing the economy, “political reform” that would include intensifying the severity of charges and punishments connected to corruption, a “health pact,” new investments in urban transport and the creation of a national council on transport that would include civil society groups and finally, new funding for education that would come directly from petroleum royalties. Dilma clearly articulated the need to “know how to listen to the voice of the street” and to remain humble. The response of the Brazilian people will be clear in the morning. It doesn’t look like anyone is ready to give up the fight just yet. The very clear and early win of a reduction in transit fares and the diversion of royalties from petroleum to go directly to education (which the PT had actually been working on for months but this is understood to be another win in the streets) has fuelled the confidence of people in the streets. This may be providing us evidence that a centre-left government is better able to move progressively when sufficient pressure is built and applied from the streets. It’s becoming part of collective consciousness expressed publicly on the bus, in taxi cabs and in the streets that this kind of pressure is getting results. •

Translations are the responsibility of the author.