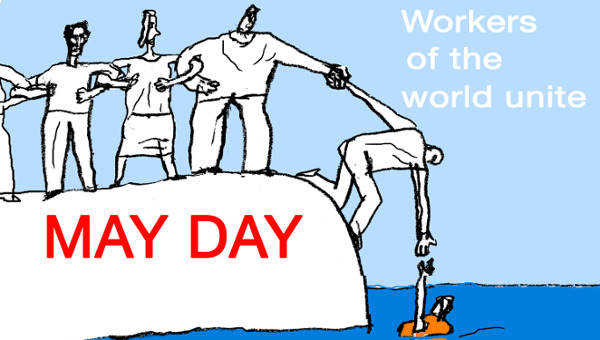

May Day 2012: Why They Are Waging War On the Workers and What To Do About It

Remember the days when bargaining was a backroom affair, or have heard about those days? When union members would only know that contract negotiations were going on when their bargaining team came out of the room and asked for ratification? This old school approach of representation was really flawed in terms of accountability and membership involvement. Yet anybody who is riding today’s roller-coaster of various levels of job action, rallies, media campaign, labour board rulings, and government offenses may wish the calm old days of backroom bargaining would come back.

Don’t bother waiting; those days are gone for good. The long-standing cooperation between employers and workers gradually deteriorated and has now been replaced by a full-blown employer attack on workers. This is true for teachers in British Columbia, Caterpillar workers in London, steelworkers in Hamilton, and Vale Inco workers in Sudbury, Ontario. It is also true for the public sector workers all over Ontario who are confronted with Don Drummond’s, a former chief economist of TD Bank, master-plan to balance the budget through cuts and layoffs. In fact, Canada is just one of the many fronts around the world where employers are on an anti-worker offensive in the aftermath of the 2008/09 world economic crisis. With this offensive, it seems, they want to finish off a job they started when the world economy was in severe crisis the last time in 1974/75 and 1980/82. Those were the days when employers first turned from cooperation to confrontation.

Don’t bother waiting; those days are gone for good. The long-standing cooperation between employers and workers gradually deteriorated and has now been replaced by a full-blown employer attack on workers. This is true for teachers in British Columbia, Caterpillar workers in London, steelworkers in Hamilton, and Vale Inco workers in Sudbury, Ontario. It is also true for the public sector workers all over Ontario who are confronted with Don Drummond’s, a former chief economist of TD Bank, master-plan to balance the budget through cuts and layoffs. In fact, Canada is just one of the many fronts around the world where employers are on an anti-worker offensive in the aftermath of the 2008/09 world economic crisis. With this offensive, it seems, they want to finish off a job they started when the world economy was in severe crisis the last time in 1974/75 and 1980/82. Those were the days when employers first turned from cooperation to confrontation.

Competitiveness, Deficits and Inflation

For roughly three decades business leaders and governments sounded the alarm of deteriorating competitiveness, run-away deficits and inflation, all the while demonstrating their entrepreneurial spirits by attacking workers, one group at a time, in the name of free markets and prosperity. For the happy few, prosperity of profits was built on the increasing misery of many. At the same time, workers whose wages were cut were offered access to cheap credit. The same big shots that constantly lament about public deficits drove private households deeper and deeper into the red and took out some credit for themselves to invest in totally inflated stock markets. The downfall of this financial house of cards, the 2008 stock market crash, turned a cyclical recession into a major crisis.

Shortfalls in government revenue and bank bailouts over the course of the crisis wrecked public coffers – and created a welcome pretext for the next, and possibly final, round of employer attacks on workers, notably in the public sector. The targeting of public sector workers makes perfect sense for the wealthy classes whose profits could only be maintained through the crisis by government money. While charging public sector unions with wrecking public finances, they had their hands deep in government coffers. Public sector workers are also an easy target because the anti-union, anti-public sector sentiments, trumpeted by governments and the moneyed interests behind them, resonate with many poor workers who either lost their union contracts long time ago or never had one in the first place.

Three decades of recurrent anti-worker offensives have created an unlikely alliance between the rich and the poor that makes it difficult today to defend anyone who still has a union contract. The poor won’t get much out of this alliance, but it is crucial to understand why many of them either support the attack on public sector workers or don’t give a damn about it. Such an understanding is needed to develop effective strategies to stop the attacks on the public sector and allow poor workers to fight to improve their living and working conditions. More to the point, to be effective union struggles need support from other groups of workers. Building alliances between workers divided by wage levels, skills, often enough by gender and race, too, is sure a challenge – but no less than the making of today’s alliance between the one per cent of the rich and the X-number of poor people.

1970s Inflation-Scare

Key to understanding why poor people, employed and unemployed, turned their backs on unions was the inflation-scare that businesses produced in the 1970s. At that time, private sector unions, namely in auto and steel, but also mining and forestry, set the pace of increasing wages and benefits for almost all workers, including those working in other sectors of the economy. Things started to change when investments in production capacities turned out to be more expensive than expected and also created overcapacities. Rising capital costs and unsellable products squeezed profit margins from two sides, so prices were jacked up in an attempt to maintain these margins. Yet, higher prices cut into the purchasing power of workers’ paychecks and unions responded swiftly by negotiating higher wages to offset this effect. Prices and wages started spiraling upwards and left many behind, such as people on welfare or pensions, whose incomes didn’t rise with inflation rates.

This was the point where employers, who had triggered the price-wage-spiral in the first place, began appealing to unorganized groups of society by blaming organized labour for the inflation and the hardship it inflicted on others. They also sought means to curb union’s bargaining power and found them in finance ministers and central bankers who cut back on spending and pushed up interest rates. The combined effect of these measures was a major recession and unemployment in the early 1980s that weakened private sector unions, which allowed companies to start increasing their profits at the expense of workers without meeting too much resistance.

Labour-saving technologies, relocations to areas offering cheap labour instead of union organizers, and a string of laws restricting union activity turned former pacemakers of the labour movement into laggards. As a result, average wages fell behind the growth of labour productivity so that an increasing share of newly produced wealth went into the pockets of the happy few. In relative terms, though, private sector workers fell behind their companions in the public sector. This was not true for the few who managed to hang on to their jobs and existing contracts but the number of these workers was dwindling and further marginalized by the blossoming of low-wage employment everywhere in the private sector.

The Tax-Scare

To appeal to these workers, governments, big businesses and their propagandists invented the tax-scare. Like it’s predecessor, the inflation-scare, it is a grain of truth mixed in with lots of lies. The truth is that taxes are a real problem for poor workers or anyone else living on low incomes. Every tax dollar they don’t pay helps them to make ends meet. The lies start by suggesting that poor people would be better off if public services were cut or privatized. After all, despite the cuts that already happened in the past, poor people still benefit more from public services than rich people.

The next lie is that rich and poor are equally desperate for tax cuts. Tax cuts are regularly designed in such a way that they benefit the rich way more than the poor. And this is despite the fact that, no matter how badly they want them, there is absolutely no need to cut taxes for the rich. Quite to the contrary, faced with idle production capacities investors prefer to put their money into financial gambling, even after the stock market crash, rather than adding to the already existing capital stock. All this money could be spent to pay for public services, the creation of additional and decently paying jobs and an ecological retooling of the economy. It could, but it isn’t.

“The challenge, then, is to build a coalition of these workers with poor people who need public services and good jobs, and the people who understand that today’s ‘profit-über-alles’-economy ruins the environment beyond repair.”

That the happy few are opposing this idea is no surprise. Since they managed to turn the crisis of the private economy into a fiscal crisis of the state they are eager to reap the profits of this coup. To them, every closed school, or, for that matter, hospital, daycare or old folks home, represents the opportunity to sell private services to the ones who can afford them and forget about the rest. Every teacher that is replaced by a computer boosts the sales of information industries and takes an actual or potential troublemaker off the payroll. The same can be said about health care and other public sector workers. The challenge, then, is to build a coalition of these workers with poor people who need public services and good jobs, and the people who understand that today’s ‘profit-über-alles’-economy ruins the environment beyond repair. To successfully defend themselves against recurrent employer offenses, public sector workers need to find common ground beyond their own ranks and launch an offensive for better living and working conditions for all but the happy few.

The ‘we are the 99%’ slogan with which Wall Street, Bay Street and other occupy protestors took to the street last fall may have been overly simplifying. The top-one-percent of the income pyramid have a whole entourage of well-to-do and powerful friends who are determined to keep things as they are. But the direction of these protests struck a new chord, one that could potentially be developed into a song of equality and justice, among humans and with nature, too, that could replace the business tune which praises public sacrifices as a good and unavoidable deed to prop up private profits. •

On the history of May Day checkout “What you need to know about May Day” by Leo Panitch.