Pakistan: Dangerous Interregnum, Catastrophic Equilibrium?

On 3rd November, while leading a Long March to the federal capital demanding fresh elections, former Prime Minister Imran Khan was the target of an assassination attempt. Thankfully, given Pakistan’s long history of violently disposing former Prime Ministers, Khan survived with minor injuries. In subsequent speeches, he has directly named and blamed the military establishment of trying to get rid of him.

Furious supporters have taken to the streets, often outside major military installations and cantonments, to demand accountability – a widespread outpouring of anti-military sentiment in central Pakistan unprecedented since the previous twilight of direct military rule in 2007. To understand where we stand now with the Imran Khan project in Pakistan however, some historical and conceptual coordinates are required.

In many senses, the emergence and quickening of the Khan phenomenon post-2007 cohered with the classic definition of a populist project: a crisis within the reigning ruling bloc; a lack of absorptive capacity due to growing exhaustion of its ideological (Islamist praetorianism), economic (aid dependency and stop-start neoliberalism on back of an already emaciated state sector), and political coordinates; and a popular upsurge from outside the ruling bloc, centered on the post-liberalisation middle classes but overlapping with more subaltern classes as well.

Imran Khan: Rise of the Outsider

It is the specific nature, the breadth and depth (or lack thereof), of the popular discontent that shaped Khan and the Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf’s (Movement for Justice – PTI) peculiar path to state power. The PTI’s program was defined around an urbane religious nationalism and a nebulous “Islamic welfare state,” a single-minded campaign against “corruption” and leakage (reminiscent in key ways of the “good governance” prescriptions of International Financial Institutions). The private media-driven celebrity and charisma of Khan, however, was not enough to paper over organizational and sociological shallowness. And thus, as subsequent post-2007 dispensations unravelled on the poisoned sword of military appeasement and economic bankruptcy (both of the ideational and balance of payments-kind), it was Khan’s party – with his untainted reputation and outsider charms – which was primed to take advantage.

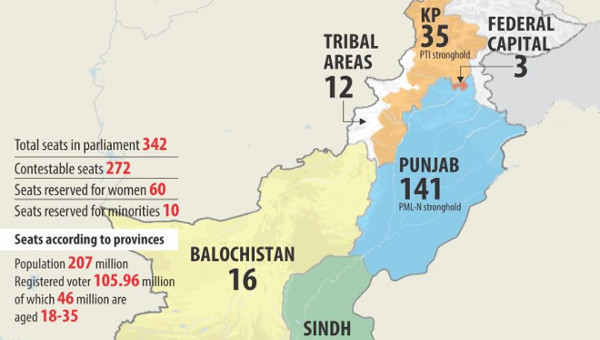

An influx of the usual mélange of big capital and landed elites into Khan’s PTI, combined with the supportive machinations of the military establishment, saw an uneasy coalition ascend to power in mid-2018: sincerely hopeful middle classes and a bulging youth population on the one hand, with a key dependence on Pakistan’s long-standing and decadent guardians of order (the praetorian guard and its allied political-economic brokers) on the other, all fused around the person of Imran Khan himself. An uneven but popular upsurge from outside the ruling bloc was thus absorbed through neutralization of its potentially democratic elements and incorporation into a military-centered, but increasingly creaking, ruling bloc.

This absorption of popular middle-class upsurge into the prevailing ruling bloc was not however easily available for an alternative “interpellation” into a progressive project – the deep ruts of a patriarchal-militarist common sense, nurtured over decades through the trenches of civil and political society, not being available for a simple “switching” of alliances with the oppressed classes below (as often intimated by theorists of “left populism”). This was conditioned in no small part by the historical defeat and restive quiescence of Pakistan’s oppressed classes in the aftermath of the post-1960s and 70s insurgency. As such, a regressive absorption of a popular upsurge was always the more likely path. Khan’s larger-than-life persona and narcissistic charisma here acting more as an index of this prevailing stasis and degeneration, rather than a cause of it.

Thus was primed the uneasy alliance with the existing guardians of order rather than with those on whose backs it was built. Instead of a popular rupture therefore, we ended up with a populist unity.

In this long arc, therefore, Imran Khan’s rise and the PTI’s absorptive-abortive project may be seen as the last attempt of the prevailing order to conserve itself even in face of its increasing unviability – to absorb burgeoning social discontent by way of its dissipation and extension through a charismatic leader. It is also this aborted populism, the uneasy conciliation of divergent interests and the unwillingness/incapacity to take the intimations of middle-class discontent into an organic alliance with Pakistan’s myriad oppressed and exploited groups, which centrally conditioned Khan’s time in power.

The Incoherence of/in Power

In office, the PTI was unable to forge a coherent organizational base to carry out the deep structural reforms required by polity and economy. Khan thus increasingly relied on the most organized group of the ruling combine i.e. the military, to paper over his coalition’s lack of organizational and economic coherence. The cabal of brigadiers, majors, generals (retired and serving), and their civilian hangers-on coming to occupy key positions in the political and economic dispensation: as strongmen for Khan’s anemic party organization, as whips to keep restive parliamentary allies in order; to run private and public institutions including the oversight body of China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (invested with much hope by Pakistan’s perennially dependent ruling classes); as brokers for the business of bureaucratic appointments and financial/real-estate chicanery; and most cripplingly, a mélange of imported IMF bureaucrats to deepen the burden of austerity and monetary tightening on the masses.

It is the political-economic narrowness of this aborted populism that also conditioned its ideological overdrive. A lack of economic and social vitality was provided ideological coherence by fevered dreams of world-stage glory. Geopolitical bluster abroad and nativist bluster at home cannot of itself substitute for a program (see, for example, the travails of the Erdogan project in Turkey). Khan’s international stances against Western Islamophobia and the imperialist dominance of Muslim populations, thus roused popular sympathy but served ultimately to distract and dissimulate rather than organize and reform the prevailing coordinates of power and pelf starting from the home front itself (including his own party).

To cap it all, the army chief General Bajwa was given a three-year extensionin late 2019/early 2020, in a rare moment of agreement among Khan and his oppositionists, all sides united by a grovelling obsequiousness to the generals – some as current beneficiaries, others waiting hopefully in line.

Most dangerously, however, in his time in power, Khan consistently reinforced highly reactionary, patriarchal nodes of popular common sense: blaming everything, from “the West” to Bollywood and women’s sartorial choices, for the increasingly visible and sensationalized cases of cruelty, rapes, and murders of women and other oppressed genders. Wanton military actions and disappearances in the peripheral regions too continued unabated, combined with wanton muzzling and intimidation of dissident activists and media personnel (moguls, influencers, and ordinary reporters – none were spared). As in previous governments, stealth privatization of public services continued to advance.

An unravelling of the uneasy alliance, however, was bound to happen. No civilian prime-minister in Pakistan has ever been able to survive the coercive charms and machinations of the praetorian guard, the poisoned chalice of military-civilian “partnership.” The COVID-pandemic provided some fiscal space, with debt and interest payments postponed. But the combination of IMF austerity, fading returns from CPEC and drying up of US largesse in aftermath of the Taliban takeover in Kabul, restiveness of the political opposition (hounded and excluded from the political power structure), and factional in-fighting within Khan’s party (especially in the dominant Punjab province) had brought things to a head by end of 2021.

In late 2021, the army chief General Qamar Bajwa, upto now Khan’s chief benefactor and ally, attempted to transfer the intelligence chief Lt. General Faiz Hameed, the regime’s de-facto whip and organizational muscle-man. Khan dithered and resisted, giving intimation of a possible plan to eventually appoint Hameed as the next army chief and thus secure another term in power. But Bajwa’s mind was made up. Bonhomies soured and the opposition sensed an opening. Picking up on changes in the establishmentarian breeze, Khan’s allied political brokers now jumped ship. Khan first resisted and then was forced out through an in-parliament vote of no-confidence, but loudly and incessantly claimed US-sponsored regime change conspiracy on the basis of an unpleasant meeting (and its accompanying internal diplomatic cable) that Pakistan’s ambassador to Washington had held with a State Department official.

The new-old combine of has-beens and their anointed progeny which came to power under the banner of the Pakistan Democratic Movement (PDM) however remained true to their rapacious and power-hungry form. Instead of calling for fresh elections to get over the taint of the highly manipulated 2018 ones, and perhaps fearing Khan’s still substantial reserves of popularity, the PDM took power in order to enjoy the perks, coddle up to General Bajwa, and to have a say in appointing the next army chief (if not in their favour then at least one not disinclined to them). Additionally, it has proceeded to implement austerity and monetary tightening with the same vengeance as the preceding PTI-IMF-Bajwa combine. Cutting already threadbare fuel and electricity subsidies added to crippling inflation both due to world-wide trends (unleashed by COVID and the Ukraine war) and rupee depreciation in the name of “market adjustment” in Pakistan.

Dangerous Interregnum

The conjuncture of Khan’s most recent resurgence is thus not a simple repetition of his post-2007 rise. Khan has gone on the campaign trail demanding immediate fresh elections with the single-minded vigour of a man with nothing to lose. Claiming murder and (international) conspiracy, he has turned on his own previous benefactors (the military), while still keeping open the hope of a route back into their favourites’ book through backdoor negotiations.

But the boot (proverbial and literal) is now on the other foot. Khan’s supporters – in his party, the media, and hyper-active digital sphere teams – have been hounded and repressed. Khan’s jilted support base, previously happy with its coddling and support by the military, now faces a measure of the same repression that the agencies handed down to their opponents over the last five years. The sense of betrayal is palpable: an unprecedented cognitive dissonance therefore now sees them express a loud critique of Gen. Bajwa and his allies within the army, even while imploring “patriotic” generals to do their duty i.e. bring Khan back to power.

Indeed, a divide is evident within the officer corps and among ex-servicemen, with many being strident Khan supporters and denouncing Gen. Bajwa’s withdrawal of support to the PTI government. All is not well in the politico-economic empire that is Pakistan’s military-industrial complex: the ever-expanding assortment of serving and retired officers, their dependents, and associated networks of contractors and influencers which form a substantial social force, as opposed to simply an economic one.

A string of by-elections on empty national and provincial assembly seats has seen the PTI win substantive majorities. Importantly, however, it is Khan himself who has been the candidate on most of these seats rather than any second- or third-tier leaders or workers of the party. Thus, even though he has not been able to draw the crowds he hoped for his Long March, his repeated wins in by-elections since the ouster show that his support base remains intact and indeed has even expanded compared to 2018.

Much speculation abounds that Khan’s Long March to Islamabad to demand fresh elections is aimed at securing the ascension of his favoured generals to the post of Army Chief come the end of November (when General Bajwa is supposed to retire). The assassination attempt last week was thus more of a warning shot for Khan to tone down his rhetoric and learn his place in the praetorian order. The religious fervour claimed by the alleged shooter both an index of both the mass lumpenisation and disenfranchisement in which millenarian fantasies find fertile ground, and of its instrumenalisation by unscrupulous spooks manning Pakistan’s state apparatus.

The coming weeks represent, therefore, a dangerous interregnum for Pakistan: a jilted populist leader with nothing to lose, and one who has retained his social base and then some; a social group (Khan’s core middle class base) unmoored from its traditional vehicle of aspiration-representation (the military); an army divided and threatening to be even more so until the drama of appointment-retirement is resolved either way.

Punctual Struggles, Organic Crisis

Beyond personality tussles and institutional machinations however, the fact remains that Khan remains the single-most popular leader in the country. The latter is down mostly to the venality and self-centeredness of Khan’s opponents. Their duplicitous and narrowly representative credentials, both dependent and fearful of the people at the same time, is indexed by a constant recycling of the same old faces – sons, daughters, nephews, and obsequious loyalists – both in power and outside of it.

Indeed, beyond their much-touted invocations of the sanctity of the vote and of democracy, it is important to note that in their respective stints in power since the 2007 transition to civilian rule, both traditional parties (Sharif’s PML-N and Bhutto-Zardari’s PPP) have constantly and consciously waylaid themselves before praetorian encroachment: whether it be through turning a blind eye toward unaccountable military operations and “disappearances” of activists, legitimizing political engineering in the peripheries, ratifying military courts, or falling over themselves to give extensions to reigning military overlords. Each successive government found itself perched on a narrower basis than the last – and at each step, extant elites preferred to shore up military over-reach for consolidating short-term power rather than mooring themselves in an effective and alternative popular social base.

At its limit, however, this incapacity to look beyond their noses, the breath-taking abdication of responsibility and imagination, and thus the constant resort to military authoritarianism and imperial dependence stems from the ruling bloc’s long-standing and permanent crisis. This crisis, in turn, is not simply one of oscillation between civilian and military rule or a purely subjective failure to counter the praetorian guard and agree on the liberal democratic rules of the game. It is linked, in fact, to the one outstanding and constant feature of the Pakistani ruling bloc over the last half a century: the lack of an integral economic project, one which can offer sustainable coordinates of accumulation and consensus for the ruling bloc, while also offering material concessions of to the masses below.

Indeed, since the exhaustion of the US-sponsored and highly-skewed Import Substitution Industrialisation project in the mid-1960s, the ruling bloc has failed to develop any coherent strategy of accumulation – one which can form the social basis for a sustainable hegemonic project and lubricant for stabilizing fraternal squabbles. Indeed, such a project of sustainable accumulation and attendant hegemony would require a level of self-abnegation, a horizon of short-term sacrifice for long-term gain, which numerous postcolonial ruling elites including Pakistan’s have proven themselves wholly incapable of.1

Productive investment, sustainable accumulation, and consensual absorption thus forgone, it is the specific insertion of the Pakistani social formation into the imperial world-system which has lent the ruling caste temporary periods of respite. Today, there are more than nine million Pakistanis working abroad and sending home remittances that support their families and help reduce the current account deficit. Between January and August of this year, remittances amounted to over $20-billion — by comparison, the Pakistani state budget for 2022–23 is $47-billion. In addition, the ruling classes have also relied upon a clientelist relationship with the US and the Gulf dictatorships.

Selling one’s people as labour power for remittances and one’s military services for imperial gendarmerie is, however, no way to live. Not only has it turned the Pakistani military into the unaccountable machine that it is today, but it has left the economy and polity vulnerable to the vagaries of imperial mood-swings. Indeed, in moments of similar disequilibrium previously, it is the mediation of imperial and sub-imperial powers (US, Saudi Arabia etc.) which has brought warring factions of the dominant and the aspirants to some sort of uneasy compromise: whether in the form of civil-military hybrids or under the banner of direct military rule. Today, however, the US has abandoned neighbouring Afghanistan in favour of geopolitical confrontation in the Balkans and East Asia, while there is increasing wariness of the Chinese with regards to CPEC investments in Pakistan. The lack of imperial mooring and patrons has left the Emperor more naked than ever been before.

A crisis, Antonio Gramsci reminds us, can sometimes last for decades and thus reveal that incurable structural contradictions have come to the fore. The current political turbulence in Pakistan arises from exactly such a structural crisis of long duration. The particular civil-military structuring of the polity is both the terms in which this structural crisis is fought out (for now) and an index of the wider malaise which it is a product of. But – and this is the crucial point – to fundamentally and permanently break this homeostasis, requires a measure of social depth and programmatic coherence that can move beyond the weapon of criticism to the criticism of weapons. Material force, as Marx was fond of saying, must be overthrown by material force – paeans to constitutionalism and liberal freedoms notwithstanding.

In the absence of such a social force which can link conjunctural machinations to the structural degeneration of the ruling bloc in toto, wrench the occasional exchange of guardians toward a permanent re-making of the social-economic order, the constant jockeying for position between different factions of the country’s ruling bloc will continue, occasionally resulting in deadlock.

One crucial (and dangerous) difference, however, seems to be operative today: the relationship with the US is not the same as it used to be, while the relationship with the Chinese cannot be what it used to be with the US. As such, there is no prospect of forthcoming imperial largesse or mediation to apply the salve on internal squabbles.

Barring the absence of such a mediatory force, with extant vehicles of representation and aspiration exhausted and increasingly riven among themselves, and with the ruling caste congenitally incapable of the self-abnegation required for a sustainable settling of scores, we thus appear hurtling toward the catastrophic equilibrium that Gramsci once warned about…

Large sections of the masses and key supports of the hegemonic order detached from their traditional vehicles; Khan, the latest (and perhaps last) popular representative of their coordination with the prevailing ruling bloc, now in seemingly intractable contradiction with it; punctual manoeuverings no longer capable of sustaining the weight of structural and permanent faultlines; the old dying and the new nowhere on the horizon; the immediate situation delicate and dangerous, the field open for violent solutions and charismatic men of destiny.

Now may come the time of monsters. •

A condensed version of this article first published on the Jacobin website.