Elections in Pakistan: A Populist Moment?

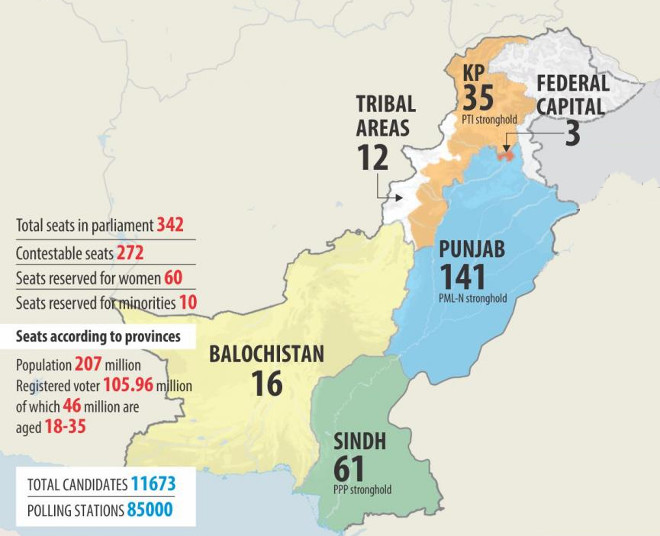

The third consecutive general election was held in Pakistan on July 25th, with the Pakistan Movement for Justice party (Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf, PTI) of celebrity-cricketer Imran Khan emerging as the largest party in parliament. For a country marred by long bouts of military rule, the continuity of (at least formal) democracy might be taken as good news. However, the conditions leading up to the elections, the prevailing balance of forces in the country, and the populist coalition forged by Khan and his party, may not bode well for the prospects of a substantive democracy centred on Pakistan’s working masses.

Leading to the Elections

The lead-up to these general elections was marred by accusations of “pre-poll rigging” by the military-dominated establishment of Pakistan in favour of the PTI and, especially, focussed on dislodging the incumbent Nawaz Sharif and his Pakistan Muslim League faction (PML-N). Nawaz himself was the product of military engineering of Pakistani politics during the U.S.-sponsored regime of General Zia (1978 to 1988) and the petro-dollar sponsored Afghan war in the 1980s. Throughout the 1990s, Sharif endured an uneven relationship with the security establishment until things came to a head in his ouster through General Musharraf’s coup in 1999. Having fashioned himself as a pro-“development” leader, Sharif secured a majority in the 2013 elections and became Prime Minister.

Sharif’s majority in parliament was, however, undercut by street agitation led by Khan and other religio-political forces, egged on by a military establishment uncomfortable with Sharif’s bid to forge closer ties with India and increase control over Pakistan’s foreign and security policy. Sharif also sought to bring former military dictator General Musharraf to an unprecedented trial in court. Tensions over foreign and security policy, the fate of former coup-maker Musharraf, and over shares/control of China’s highly touted Belt and Road Initiative’s Pakistan leg (called the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, CPEC) boiled over in a protracted war of position between the civilian elite and military establishment.

Revelations in the Panama Papers of the Sharif family’s assets outside Pakistan triggered a series of court investigations and media trials, resulting in Nawaz Sharif’s legal disqualification and ouster from premiership in 2017. A hyper-active judiciary (the product of Pakistan’s last round of anti-dictatorship struggle in 2007-08), and an assertive military establishment found common cause in a highly selective “accountability” drive which, of course, excluded well-fed bureaucrats, judges and generals. This was combined with increasing encroachment of the military establishment in different spheres of governance and policy-making.

With the establishment’s deteriorating relationship with the strongman regime in Washington, accompanied by increased closeness to China, even a rhetorical commitment to procedural democracy and basic civil liberties has been abandoned at the altar of defending “national security.” Military operations in peripheral parts of Pakistan – such as Balochistan province and the Federally Administered “Tribal” Areas – for the past decade has already resulted in a situation resembling martial-law in these areas. Recently, the sphere of military operations was increased to Pakistan’s financial metropolis, Karachi ostensibly to “improve law and order” and clear the ground for incoming Chinese capital, while military courts were instituted to bypass the slothful criminal justice system and deal with “die-hard terrorists.” When the high-handedness of the security establishment came under criticism by popular, non-violent movements such as the Pashtun Tahaffuz (Protection) Movement (PTM), the program of press censorship and extra-judicial abductions of the military’s critics was expanded from the peripheral to the “core” areas of the country.

It is in this atmosphere of intimidation, censorship and “accountability,” that the country approached the July 25 elections. The incumbent N-league was brazenly suppressed, its leader Nawaz Sharif and his daughter jailed over corruption charges, while many leaders were reportedly forced to leave the party and/or join Khan’s PTI. The election process itself was marred by several irregularities: more than 350,000 army personnel were deployed inside and outside polling stations, the vote counting system suffered “technical difficulties” shortly after the end of polling, while the number of “rejected” votes was found to be greater than the winning margin in at least 35 constituencies. Ultimately, the PTI emerged as the largest party in parliament and, with the help of some independents and smaller parties, Imran Khan was elected Prime Minister.

PTI: Crisis and Populism

Khan and the PTI themselves are products of the changing balance of class forces in Pakistan. A celebrated former cricket captain and philanthropist, Khan started his political career as an anti-corruption crusader in 1996. His politics, though, really took off in the late 2000s as a burgeoning middle class, products of a liberalizing economy and expanding services sector, found in Khan a vehicle for their technocratic-meritocratic values and aspirations. Previously having found political articulation through the civil-military bureaucracy, the end of Gen Musharraf’s military rule was marked by a crisis of absorption of this burgeoning section of the population. This was accompanied, in the context of the so-called War on Terror, by an increasing exhaustion of the complex of exclusivist Islam and praetorianism which had provided ideological grist to the ruling bloc since the late 1970s.

The PTI represented a populist intervention in this crisis-ridden conjuncture: an economic program based on (nebulously defined) “anti-corruption” and decreasing leakage, appeals to an “Islamic” welfare state, and invocations of a “moderate” and urbane Islam best embodied in the popular perception and personality of Khan himself. The private media, professional associations, hyperactive internet forums, and charity initiatives (exemplified by Khan’s own free cancer hospital and foundation) became key apparatuses in the terrain of civil society, whereby the new middle class attempted to forge an “ethical-political” hegemony. In the absence of organized bases of working class power (such as labour and student unions), such institutional apparatuses have become crucial avenues for shaping and influencing Pakistan’s power politics.

However, while the fast growing, professional middle class (estimated to be upwards of 50 million out of a population of 220 million) formed the hegemonic core of the PTI, the structuring of the political terrain worked against its ascension to the corridors of state and executive power. Concentrated overwhelmingly in the urban core of the country, the middle-class base of the PTI was constantly frustrated in its attempts to attain the hegemony over space crucial for attaining power in constituency-based parliamentary politics. Khan and the PTI realised that dominance of social media and television airwaves is one thing, while dominance over (non-virtual) space is quite another. Something would have to give.

Such a re-structuring and spatial expansion of the PTI-project in the 2018 elections was attained through three crucial openings. Firstly, the influx of new – and especially young – voters on electoral rolls was almost completely absorbed by the PTI. While the two other major parties, PML-N and PPP, maintained their vote numbers from the 2013 election, the increase in the number of total votes cast for PTI (about 9.2m) exceeded the increase in number of votes cast in aggregate (about 7.6m). Second, the clash between the military-judicial establishment and the PML-N widened splits in the ruling elite, while subsequent terrain-engineering through suppression of rivals favoured the PTI’s election campaign. Third, and crucially, the PTI’s opening up to Pakistan’s landed and big capital elite, already underway since 2012, was vastly accelerated. Political brokers in rural and peri-urban constituencies – ever sensitive to the cajolements and directions of the establishmentarian breeze – pledged allegiance to Khan’s “anti-corruption” platform and boosted the spatial-social spread of PTI’s electorate. Thus, the PTI and Khan headed into elections with a terrain clearer than ever before, and with a set of social-spatial alliances which put it in prime position to finally translate its hegemony from the virtual spaces of the Internet to the corridors of parliamentary power.

Between Tragedy and Farce:

The Pitfalls of Elite Politics

It is also within these openings for the PTI that the abject failures of Pakistan’s mainstream, incumbent parties can be glimpsed. Dominated by big capital, landed elites and political entrepreneurs, these parties have provided neither a voice to Pakistan’s burgeoning youth and middle class, nor an alternative model of development and redistribution beyond the crumbs falling from patronage networks. Parties (and governments) are run through kitchen cabinets dominated by brothers, daughters, cousins, and various assortments of kin mediated through blood and money. The parties’ leaderships and platforms have scarce representation/input from grassroots workers.

“Development” – where diverging from vertical patronage networks – is reduced to glitzy and high profile “mega-projects” and “model projects,” which grease the palms of brokers and contractors around party leaderships, while having little to no bearing on wider issues of social and geographic inequality. As such, mainstream parties’ attempts at hegemony in the name of the nation’s common interests and their quest to cut the military down to size in key spheres of policy-making, is regularly brought to heel due to their own lack of popular support and subsequent susceptibility to populist upsurges (such as that of the PTI’s).

It is exactly here, in both their desire to cut down on praetorian machinations and their structural, almost congenital inability to provide enough concessions to the masses for attaining the desired popular legitimacy, that all threats of “rejecting” elections and mass agitation from incumbent power holders in Pakistan came to naught. Further, these parties remain prey to more ambitious and ruthless contenders for power who can present themselves as acceptable to the ever-ready military establishment (as Imran Khan has positioned himself over the years).

In effect, we have an elite unwilling and almost incapable of living up to their own promises, and who fail to be hegemonic beyond superficial invocations to Islam, nationalism and ‘development’. For all their talk of ‘democracy’ and ‘civilian supremacy’ will come to naught until political parties, their modus operandi, and their wider social-economic platforms are re-structured into truly pro-people projects for all of Pakistan’s different nationalities. In the absence of such, the incumbent ruling classes resort to a politics of vertical patronage networks and high profile infrastructure projects to build a weakly hegemonic order, susceptible always to the manoeuvres and encroachments of a rapacious praetorian guard.

In effect, we have an elite unwilling and almost incapable of living up to their own promises, and who fail to be hegemonic beyond superficial invocations to Islam, nationalism and ‘development’. For all their talk of ‘democracy’ and ‘civilian supremacy’ will come to naught until political parties, their modus operandi, and their wider social-economic platforms are re-structured into truly pro-people projects for all of Pakistan’s different nationalities. In the absence of such, the incumbent ruling classes resort to a politics of vertical patronage networks and high profile infrastructure projects to build a weakly hegemonic order, susceptible always to the manoeuvres and encroachments of a rapacious praetorian guard.

Fearing both the masses and the praetorian guard (for different reasons), they are forced to lean first on one and then on another for an always tenuous, often short-lived legitimacy. To channel the Marx of the Eighteenth Brumaire, Pakistan’s ruling classes are “bound to fear the stupidity of the masses so long as they remain conservative, and the insight of the masses as soon as they become revolutionary.” And thus is (formal) democracy in Pakistan, and the elites who have come to become its bearers, condemned to alternate between a sense of tragedy and a sense of farce.

The “Long March” through Civil

and Political Society (or Lack Thereof)

Moreover, it is also in the (seemingly) oppositional, populist coalition forged by Khan that PTI’s politics is likely to find its Achilles Heel. For its fulfillment of promises of an Islamic “welfare” state, Khan will have to tax big business which is amply represented in his party’s inner circles. For its promise of building thousands of homes for the lower middle class and the poor, Khan will have to contend with Pakistan’s highly influential real estate mafia (including the military and party luminaries). For the promise of instituting an egalitarian educational system in Pakistan, he will have to contend with organized interests around privatization of education (which, paradoxically, Khan’s middle class base itself is a product of). For his promise of having equitable and friendly relations with neighbouring countries, he must confront the myopic and isolationist calculations of Pakistan’s military establishment. Add to that the pressures of increasing oil prices, leading to rising import bills, a declining export and manufacturing base, decreasing remittances, and the program of cost-cutting and privatization which is sure to be part of a looming IMF bailout.

It is for the fulfillment of these promises that a vast, emerging and young section of Pakistan’s population has pinned its hopes on the PTI and Imran Khan. The danger, of course, remains that in trying and failing to tie together so many varied interests and promises, Khan and his party may resort to the campaign trail rhetoric of “enemies” and “traitors” to paper over contradictions and shore up the party’s support base. Keeping in mind the shifting imperial mooring of the Pakistani state, the general (pun-intended) air of political suppression in the lead-up to elections, Khan’s history of exclusivist rhetoric, and his well-publicised personality traits of aloofness and narcissism, Pakistan’s descent into further authoritarianism cannot be ruled out.

For the short-term though, Khan’s political capital and support among increasing and influential sections of the state and society will see him through. What happens to Khan and Pakistan’s latest populist moment in the long-term is, of course, a matter of political practice and down to the mode of incorporation of middle and lower classes in the country’s changing ruling bloc. However, we can find clues to the long-term future of PTI’s politics and the changing ruling bloc in Pakistan a focus on the question of class alliances. In their quest for social and spatial hegemony, the new middle class (and the PTI) have made a strategic choice: to forge alliances with prevailing ruling classes and oligarchic state institutions (such as the military) over the subaltern classes of Pakistan. Such a strategic choice is of course conditioned by a conjuncture marked by the virtual absence of sustained working class organization in Pakistan. In effect, what we have is a passive revolution-type situation: a Bonapartist state and a ruling bloc in crisis is attempting to absorb an upsurge from outside the prevailing ruling bloc, with a new material-ideological hegemonic project based on “development” (through Chinese capital) and a reformulated complex of Islam and praetorianism.

As far as such dubious class alliances preclude a more progressive social-political project, the PTI and Khan are left to deal in high-sounding bluster and populist rhetoric. The “long march” through the trenches and ditches of civil society, so crucial for a viable hegemonic project centered on the popular classes, has been assiduously avoided, compromises have been made, and silence adopted toward key reactionary forces and institutions in the domains of civil and political society. For example, while Khan’s compromises with the military establishment have already been mentioned, a telling silence and even an accommodating stance was adopted toward fascist forces such as various Islamist groups organized around persecution of minorities and religious heterodoxy. With no progressive constituency to fall upon, and the ruling elite’s international legitimacy in tatters due to their profligate ways and geopolitical (mis)adventures, Khan and the PTI remain beholden to oligarchic elites and institutions, and reactionary forces are expected to gain strength.

As such, in his one month in power, Khan has vacillated on issues such as approaching the IMF, and over accommodating religious minorities in government. Mad-cap schemes of building mega-dams through “donations” by diaspora Pakistanis have been introduced, while the Chief of Army Staff has doubled down on the “indispensability” of CPEC and growing economic and security alliance with China. Moves are also afoot for a reduction of financial autonomy for the provinces ostensibly to free up resources for ever-increasing security expenditures. This, if followed through, will do with grievous harm to Pakistan’s already weak federalism. Combine this with the continuing attack on civil liberties and the poor state of labour and women in the country, and any progressive agenda that the PTI might have brandished seems far from the horizon.

It is also in the question of class alliances and the “long march” through the trenches of civil society which provides a useful barometer of comparison to other iterations of right-wing populism, such as (to take two examples) in Turkey and India. While in some respects, the PTI has a very similar professional middle class core as the BJP’s reformulated, Modi-ised hegemonic project in the post-Babri Masjid era, right-wing populisms in both Turkey and India differ from Pakistan in key ways. For one, and notwithstanding their more recent troubles, the current regimes in both Turkey and India are based on much longer and more deep-rooted genealogies of (post-)Islamist and Hindutva organizing, respectively. The AKP (and its previous analogues) have rootedness in long-standing Islamist political traditions in Turkey and beyond, a socially-temporally greater anchorage in the Anatolian bazar classes, and key bases of support among Turkey’s urbanizing poor mobilized through Muslim Brotherhood-style service delivery and patronage networks over the last three to four decades. On the other hand, the RSS-BJP combine is the very personification of the long-standing fascist project in India, and have been strategically cultivating Hindutva fundamentalism in the spheres of civil and political society for close to a century now. Thus, unlike the PTI and its professional middle class core, projects of religious conservatism and populism in India and Turkey are distinguished by their “long march” through the trenches of civil and political society, and thus much greater anchorage for their respective hegemonic projects within the ambit of the “integral state.”

In comparison, while the middle class itself in Pakistan is a rising force both demographically and socially, its hegemonic project has nowhere near the sophistication and deep-rootedness of its Turkish and Indian counterparts. As such, the social and spatial coordinates of the PTI’s hegemonic project remain relatively shallow and beholden to other reactionary forces in civil and political society (such as the military and various Islamist groups), and thus much more vulnerable to challenges. In this context, while the sharpening of the passive revolutionary project may herald an even greater resort to coercion and political suppression, the tenuous hegemony also provides contradictions and spaces (both literally and metaphorically) for the intervention of alternative (progressive) forces. This of course remains difficult because of the absence of viable left and labour organization after the historic fall of the Left in Pakistan from the high era of the 1960s and 70s. In a sense then, the traditions of long dead generations really do weigh like a nightmare on the brains of the living.

In comparison, while the middle class itself in Pakistan is a rising force both demographically and socially, its hegemonic project has nowhere near the sophistication and deep-rootedness of its Turkish and Indian counterparts. As such, the social and spatial coordinates of the PTI’s hegemonic project remain relatively shallow and beholden to other reactionary forces in civil and political society (such as the military and various Islamist groups), and thus much more vulnerable to challenges. In this context, while the sharpening of the passive revolutionary project may herald an even greater resort to coercion and political suppression, the tenuous hegemony also provides contradictions and spaces (both literally and metaphorically) for the intervention of alternative (progressive) forces. This of course remains difficult because of the absence of viable left and labour organization after the historic fall of the Left in Pakistan from the high era of the 1960s and 70s. In a sense then, the traditions of long dead generations really do weigh like a nightmare on the brains of the living.

Weak Sutures, Tenuous Hegemony

Stuart Hall once likened the practice of hegemony within a disequilibrium-wracked capitalism as the process of “suturing” wounds which continually appear in the body politic, in civil society, and in the economy. The process of managing contradictions is one where the festering-expanding wounds of the body politic are sutured, until the many sutures themselves fall apart and a new hegemonic project with different kinds of suturing must be instituted to manage the disequilibrium and its wounds.

Crises in capitalism rarely appear as all-encompassing crises of the whole system. More often, crises in different spaces, regions, and/or nations and at different, mutually constitutive/conditioning levels of the system (such as the economic, political, ideological etc.) develop in their own time and with their own temporality. As such, an effective hegemonic project and a viable hegemonic force must serve to suture together these different levels, their crises, and their different temporalities.

In Pakistan, wracked as we are by multi-level and multi-spatial crises, when the weak suturing of the latest (tenuous) hegemonic project starts to come off, we will be left adrift in search of an organized social force which can represent and, in effect, suture that crisis. It is here that the absence of a viable progressive force will be, and is being, sorely felt. For those who aim to rebuild the devastated bases of working class power in Pakistan, the task remains not only to read the conjuncture in all its complexity, but to find the openings, slippages and contradictions which can unravel the prevailing historic bloc in favour of a new, substantively democratic one. For the foreseeable future though, with no viable organization to effectively represent our multi-level crises, with no effective suturing force on the horizon, the time, as the old Bard put it, remains truly out of joint. •