Union Organizing at Amazon

Has the Labor Board Provided a Way Forward or Another Detour?

In 2020, Amazon workers in Bessemer, Alabama, voted on whether to be represented by the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). The union lost the vote, due in part to the hiring of the infamous union-busting agency the Pinkertons, and an extensive and intrusive anti-unionization campaign. The US National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) first found enough evidence of Amazon’s interference at Bessemer to call for a re-vote and, in December 2021, reached an agreement with Amazon about ensuring that Amazon workers’ basic rights to organize are upheld by the company. Both of these verdicts have aided the growing narrative that a pro-union shift has taken place within the United States government with President Joe Biden and the Democratic party at the helm of this ostensibly progressive reorientation. But are these rulings as pro-worker as they seem?

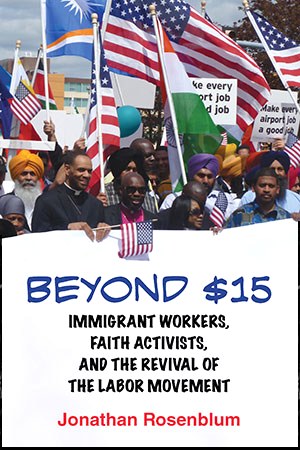

Tori Fleming and Matt Davis spoke with Jonathan Rosenblum to find out. A second part to the interview with Jonathan on lessons for union organizing will follow. Tori and Matt are involved in a variety of activities related to union organizing and media coverage of the labour movement.

Matt Davis (MD): Thanks so much for joining us, Jonathan. To start, would you mind telling us a bit about your background, specifically when it comes to organizing, and what you’ve been working on lately?

Jonathan Rosenblum (JR): I’m really excited to be in this discussion with Canadian comrades about what’s going on here in the States and the prospects for organizing in the period ahead. I actually started out many decades ago as a rank-and-file union member in the newspaper industry, as a member of the International Typographical Union, which now I think is part of the Teamsters. From there, I became a full-time union organizer working in the Deep South in the 1980s, and then in New England before I came out to Seattle in 1991. I’ve been doing a lot of different organizing over the decades, healthcare organizing, industrial organizing, and so on. In 2011, the union (Service Employees International Union – SEIU) asked me to head up what became the first successful fight for $15 in the country. That was the SeaTac (Seattle-Tacoma) Airport workers fight, which resulted in an initiative passed by the voters to require an immediate $15 minimum wage for all of these airport workers. It was largely immigrant workers at SeaTac Airport, which is our main international airport, just outside of Seattle.

For the last five or six years, I’ve been working primarily with our socialist city council member Kshama Sawant on a number of projects. We’ve been fighting for and winning some really important renters’ rights here in Seattle, also passing a historic first time ever tax on Amazon and other big businesses here to fund affordable housing and Green New Deal projects. That was a tremendous battle as well. I’ve recently stepped out of that role, while I still stay close to the work that Kshama and the Socialist Council Office are doing, I am focusing my work with academic workers up and down the West Coast of the United States.

Working with the United Auto Workers (UAW), which is not just for auto workers, but also academic workers. In California, the vast majority of academic workers are struggling every month to pay the rent. These are graduate students, teaching assistants, research assistants, postdocs, graders, tutors, and the like. They are organizing a huge contract campaign where during this year 48,000 UAW members in the University of California system will be having contract negotiations and are going to be demanding housing justice as a major part of that fight. And then up here in Seattle, 7000 workers at the University of Washington are also in a similar struggle, although in a somewhat different timeline. I’m very excited that university workers are coming together to fight for housing justice, and really to fight for the entire community’s right to live affordably. So that’s the work I’m doing in 2022.

MD: I wish we had the time to ask you about all of those projects! I think we’d like to turn to Amazon and its recent settlement with the NLRB. So, Amazon has come to a settlement with the Labor Relations Board around the issue of Amazon’s employees having the right to organize and how that right is communicated. From your point of view, what are some of the most important details of the settlement and what are the potential impacts or implications for workers both inside and outside of Amazon?

JR: I would say to Canadian comrades that it’s obviously a good thing to have this settlement. It validates the workers’ demands for rights. We also shouldn’t exaggerate the actual value of this settlement from the National Labor Relations Board. There are two things to look at in terms of the settlement. First, the legal and practical implications, and second, the political and organizing implications.

Let me talk first about the legal and the practical side, just so that your audience has an understanding. The Labor Board found, to the surprise of zero workers in this country, that Amazon violated workers legal rights. The Board found that Amazon illegally threatened, harassed and retaliated against workers who were organizing unions. In the settlement, the Labor Board required that Amazon post notices saying they won’t do these things in the future. But there’s no admission of guilt required. There are absolutely no penalties of any sort.That’s how federal labor law works in this country. What’s different about this particular settlement from others is the posting requirement: the requirement for Amazon to post notices that say ‘here are your rights’. It also requires Amazon to email that notice to all of its workers. This is more than a million people in this country. That requirement is new. I want to come back to it when we talk about the organizing implications.

The other thing that the Labor Board found is that Amazon managers were illegally discriminating against worker organizers by restricting their access to break rooms, parking lots and other non-work areas before and after their shifts, when other workers were not restricted in the same way. The Board ordered Amazon to rescind this discriminatory rule. Now, there’s been a lot of celebration about this particular ruling, and how it will open the doors for workers to organize much more freely at Amazon.

I certainly hope that does turn out to be the case, but I think people need to understand that Amazon is not going to simply let this happen. All Amazon has to do to get on the right side of the law is issue a new company rule limiting worker access, and to issue the access rule in a non-discriminatory way. In other words, to craft the rule so that it doesn’t name union organizing as any particular restriction. In fact, if you read the last sentence of the posting, it explicitly authorizes Amazon to do exactly that after the 60-day notice posting period is over. So, in the scheme of things, the settlement is a slap on the wrist for Jeff Bezos. Maybe not even a slap on the wrist, more like a tap. It’s not going to change Amazon and its implacable hostility toward workers and unions.

What’s more interesting to examine are the political and organizing implications of the settlement. It’s extraordinary that the company is now going to have to send out notices to all of its workers. Disseminating the posting is certainly going to boost confidence of workers who are inclined to organize. It validates their critique of the company’s illegal behavior, though I think it’s way too soon to tell whether it will sufficiently embolden workers to move from inertia and fear to organizing. I think it would be a little panglossian to imagine that this is somehow going to open the floodgates of organizing at the company. It’s not. Amazon is going to continue to try to snuff out unions at any expense. They’ll just be a little more careful.

I think it’s also important for Canadian workers to understand that what’s an abuse of worker rights and what’s a violation of labor law in the United States are two very different matters. Labor law is very narrowly constructed. The NLRB found that Amazon had an after-hours access rule that was applied in a discriminatory manner, and therefore it violated labor law. It’s not illegal for Amazon to do most of the things that it traditionally has done to bust unions or stop unions from growing, such as holding mandatory anti-union meetings, or threatening people in ways that don’t violate the law. Management lawyers are quite adept at training companies how to go right up to the edge of breaking the law without getting into legal jeopardy. I’m sure that is what Amazon is training their managers on right now.

Let me give you just one example. There’s nothing illegal under US labor law for management to force workers to attend mandatory anti-union meetings, where they browbeat workers about how terrible unions are. In fact, that’s exactly what Starbucks is doing at every single one of their stores where workers are standing up and forming unions. It’s not illegal for management to tell lies, to exaggerate, or to threaten through implication. So for instance, it is illegal under US labor law for the boss to say, “you will lose your job if you organize.” However, it’s not illegal for him to say to the workers that, “if you organize, you could lose your job. We never have to sign a contract, and look at what happened to all those union workers down the street who got laid off after organizing.” Now that’s a pretty intimidating message coming from the person who controls your paycheque. All that is legal under US labor law.

It’s so important for people to recognize both in your country, ours, and elsewhere, that once American workers who don’t have union protection punch the time clock – that’s 89% of the workforce – they give up their free speech and other basic rights. There’s nothing democratic about the American workplace and this ruling doesn’t really fundamentally change that brutal reality. Workers need to organize, demand their rights and make the boss pay attention through collective action up to and including strikes. That’s what’s going to deliver justice for Amazon workers, not a particular ruling or settlement from the Labor Board.

MD: Some progressives have argued that this settlement is a major concession by Amazon, that this is a defeat for them in some way. Does this settlement represent a shift from Amazon away from more overt forms of anti-union coercion toward something a little more covert?

JR: Well, it’s a concession by Amazon, just like when there is enough pressure on them to commit to a $15 minimum wage. They did that like any capitalist boss. They assess the field and the state of play, and they will make whatever minor concessions allow them to continue on the course that they’re headed on. So yes, it is a minor concession in that for 60 days they have to permit greater degrees of people doing organizing in non-workspaces. But they’ll still reinstitute the new access rule that will lock that down. Workers who start to organize at Amazon will still be confronted with anti-union meetings, hostility, threats, firings, and so on, just like it’s always been.

Tori Fleming (TF): I think your point about Amazon instituting a $15 minimum wage is interesting. Amazon was able to leverage the fact that they were one of the first big box employers to concede to that demand to paint themselves as a bit more progressive. What role do you think that the $15 concessions, as well as the previously mentioned NLRB ruling have within that general history of Amazon attempting to try to undercut criticisms waged against them?

JR: Well, I think what’s important for us who are on the left is to have a proper assessment of the importance of the ruling and not to inflate it or play into the capitalist PR game that this is somehow a shift in posture or policy. It’s not. Whether it’s Amazon or Walmart or Starbucks, they all operate ready to make minor adjustments in their approach to things and deal with crises of the moment, whether that happens to do with the supply chain, labor relations, or even the jockeying that goes on between these big capitalist competitors. But they’re all on the same side of the class fence in the end, and they’re all going to work together to try to keep workers down.

How do we take this ruling? We should say, this company is actually outside the law and this is exactly why workers need to organize. We should also say, this is not a panacea, not even in the ballpark, and that workers have to organize and fight back. We have to challenge the very premise that this company should be able to make profits off of our labor while destroying the planet in the process.

TF: I agree that the PR aspect is important for us to understand, especially as Amazon seems to have an especially savvy PR team behind them. One example that comes to mind is the mainstream media, particularly the New York Times, praising Amazon for their COVID-19 testing and vaccination policies while numerous reports have been made of Amazon’s atrocious record when it comes to workplace safety. What would you say in response to those celebrating this moment as a shift away from Amazon’s behaviour toward its workers in the past? Will Amazon now become more responsive to addressing complaints made against it?

JR: This actually doesn’t change much. The NLRB in the scheme of things is a fairly small agency in the federal government. Amazon has a direct channel to the commanding heights of political power in the country. The NLRB is a small nuisance that they can easily brush away.

As for official complaints, somebody can file a charge with the Labor Board, the board would need to investigate and it could potentially take many months. For example, what happened in Bessemer, where Amazon violated all kinds of workers rights, and I don’t mean, just labor law violations, but basic human rights violations. The workers were intimidated to vote against having a union. A year later the Labor Board says, well, let’s have a do-over election. By this point any semblance of the potential for democratic vote has been absolutely destroyed by what Amazon’s done over the last year. So, for the Board to now come in and say, ‘we’re going to fix it’ doesn’t really solve the problem for workers. I do hope the workers win. But the Labor Board is not going to get Amazon to change its behavior in any significant way.

TF: There is this idea out there, that due to this settlement, some of the administrative processes at the NLRB can be bypassed to punish Amazon for violations much more easily. Is this accurate? Could we expect more enforcement against Amazon in the coming months?

JR: You might be referring to a couple of recent articles on the default statement in the settlement. The statement basically says the NLRB can go to court for enforcement and Amazon can’t argue the facts. That’s a pretty standard statement. That’s been a part of all settlements the NLRB has done for the last 75 years, and probably a standard legal settlement even outside of the NLRB too. Once you agree to something in a stipulated agreement, you can’t then go back on it and try to re-litigate it. You don’t get two bites at the apple. That’s a basic legal principle.

I think the bigger question is, why would the New York Times and the mainstream media want to celebrate this? Why would they tell us we should celebrate this as a great victory for workers? That is part of the propaganda of the political and business establishment. That this is something really very different, “now workers do have these rights, and Amazon is going to be schooled.” Frankly, that’s just a lot of misdirection and BS. I don’t know how else to put it. They may want us to believe that things are going to be different, but they are not. We still are dealing with a company that has implacable hostility to workers and to unions.

MD: We’re interested to hear what you think this moment in Amazon’s development as a company means for organizing, especially directly on the shop floor itself. Do you have any thoughts around what the current moment holds for some of the independent workers groups organizing at Amazon, like various ‘solidarity unions’ that focus on direct action and may not necessarily have direct connections to some of the established unions?

JR: I have no way to independently judge – you would have to go talk to the workers. I think for most people, it’s nice to get the posting in the mail, but it doesn’t change the brutal reality of how people are overworked, abused, underpaid, and treated horribly every day, in and out in the warehouses. Let’s remember, it’s not just a company that deals in logistics. This is a tech company, and this company controls a significant part of the internet. There are a lot of high-tech workers too. Increasingly, in Seattle for instance, where Amazon is basically headquartered, many mid-level Amazon workers are unable to afford to live in the city, because of Amazon’s growth and how it has really distorted the housing market. They’ve promoted a lot of luxury developments at the expense of affordable housing. So, from the perspective of Amazon workers, I think the challenges are still every bit the same as they were.

I want to go back to a point you made, Tori, about reactive messaging, just to put a final note on it. From a PR standpoint the company is saying to themselves, we have to create a different message, because if we don’t act, the message is going to be that Amazon kills workers. And Amazon does kill workers. That message is intolerable to the establishment, not just Amazon, but to the political and economic elites of this country. So, the narrative had to be redirected to things like ‘Oh look, they’re providing masks, they’re providing vaccines’. Well, that’s not going to bring back the lives of the Midwest people who were killed because they were forced to continue working during a tornado.

TF: One concern is the way that Amazon goes about making even the most basic of changes. It often works to do precisely what you are saying, conceal the reality of what’s actually happening within Amazon workplaces. In light of that, are there ways that workers can use this settlement in a way that actually can develop their workplace struggles further and actually promote solidarity?

JR: Certainly, from a public standpoint, workers can point to the settlement and say, ‘Amazon violated our rights’. However, the truth is there’s actually no admission in the settlement that Amazon violated workers’ rights. That’s why I really would encourage us to think about the bigger picture of organizing and put the settlement in its proper context. It’s certainly better to have it than to not have it, but it’s not going to transform things.

I think you have to look at the day-to-day reality of what workers are struggling with. The question for workers who are organizing, either through informal solidarity networks or through formal unions, is: “Are they going to learn some of the fundamental lessons from the first round of union elections in Bessemer and adjust the organizing strategies and tactics so that workers can be successful?”

I want to give you an example. At Bessemer, the staff union organizers actually thought they were going to win. They did not have a full assessment of the workplace. They did not have a functioning organizing committee that was broad and fully representative of a majority of the workers. They did not do house visits. They also did not have majority structure tests, as Jane McAlavey calls them, to assess and determine how strong the union actually was. So it was a shock to many of them when the result came in so overwhelmingly against the union. It was not, unfortunately, a surprise to some of us who were looking at it more from a distance and saw that the basics of organizing that working class people have to do to build durable power in taking on a company, were not done. Until you do them, you are not going to prevail.

Let me contrast that with the Starbucks organizing that’s going on. In Bessemer, it was hard to see the workers who were involved. There were a few workers who were out there publicly, but not a lot. In contrast with the Starbucks organizing, you’re seeing petitions signed by all the workers at a particular store, very publicly saying ‘we are the union’. It makes it much harder for the boss to third-party the union in that case, because the workers have publicly identified themselves as the union. It also makes it harder for the boss to intimidate people, because people have already said, ‘we’re public, we’re not shy, we’re not hiding who we are’. So that builds a much more solid foundation for workers to be able to endure the harassment, the threats, the intimidation, the firings, that are certainly going to continue from Starbucks.

I hope that in the second round of Bessemer, and in other organizing that’s done at Amazon worksites, that people understand those lessons. I hope they recognize that you have to have a representative organizing committee, you have to be public and out front, and you have to demonstrate majority support if you’re going to overcome everything that the company is going to throw at you.

Let me give one more example. Three years ago, before the pandemic, a number of Amazon tech workers, organized, fought for, and got the company to concede on reducing its emissions, reducing its carbon footprint and going net zero by 2040. The point is that these largely tech workers were able to force Amazon to make this concession on climate justice issues through one-on-one organizing in the workplace, followed up by a lot of media publicity. Though it’s not over yet, it’s still not enough of a concession by any stretch of the imagination.

What’s interesting for us as leftists or socialists is to imagine what happens when the tech workers and the warehouse workers at Amazon actually combine forces and say we’re all in this together and we want to struggle together. Because again, Amazon is not a warehouse company. It is a very broad company that spans many different industries, warehousing and logistics is just a small portion. The single biggest element of Amazon is actually Amazon Web Services. AWS controls a substantial portion of the internet as you may know. Real worker power at Amazon is only going to be realized when we figure out how to unite tech, warehouse and other workers in this huge mega-corporation together, nationally, and of course, internationally as well. •

Part 2: Lessons for Organizing.