Shock Therapy: Public Funding and the Crisis at Laurentian University

Here we go again. A major crisis. Governments cutting taxes. Bailouts in the billions for banks and corporations. And suddenly public services – including universities like Laurentian – are on the chopping block. This has been the story in Canada, the United States, Australia and many other countries over the past thirty years.

And now, with Sudbury Ontario’s Laurentian University declaring insolvency – the first public university to do so in Canadian history – we can anticipate even more public sector “crises” to come in the very near future.

Claiming they have “unsustainable” debts, Laurentian University has gone to federal court claiming they need to terminate many of their professors and cut programs. Warning other universities that more financial oversight is coming, Ontario Colleges and Universities Minister Ross Romano said that “more dramatic and immediate action” will be needed.

State of Universities

But there is nothing unsustainable about Laurentian University – though it has suffered poor financial management for years. Nor do any other Canadian universities have “out of control spending” – though several (like Laurentian) are now facing hardship with the drop-off of international student enrollment and suffering from decades of chasing private sector dollars.

Rather, the problem that Laurentian and other Canadian universities are now facing is something completely different – governments crying poor in the middle of a crisis while bailing out the rich and gutting social program spending for everyone else. All this, while washing their hands of any financial responsibility, and repeating that “there is no alternative.”

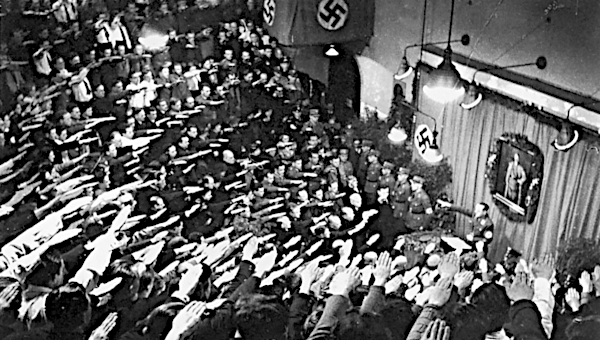

Indeed, the problem facing Canada’s post-secondary education sector is much better characterized by what Naomi Klein has famously called “the shock doctrine.” This strategy, she points out, is a well-used one by fiscally conservative governments, when in reacting to an economic crisis, public officials routinely look to take advantage by pushing regressive policies through for the benefit of the wealthy few.

Australia has been down this road before, and has already kickstarted its next round of austerity by demanding its cash-strapped universities cut more than seventeen thousand jobs in recent months. In the United States too, the current financial outlook of municipalities and universities is dire, as revenues have plummeted with more people unemployed and students staying home. This has led American colleges and universities to shed thousands of jobs at an unprecedented rate.

How to Restructure in a Crisis

The clear outlines of a similarly regressive strategy are now appearing in Canada as well. Just as in the United States, over the past year, the federal government has doled out billions to corporations in tax deferrals, loans, and subsidies, while directing the Bank of Canada to buy up more than $169-billion in bad business debt and shaky loans.

Now, corporations and banks are flush with cash, stock and financial markets are booming, and Canada’s top billionaires have increased their wealth by more than $53-billion in less than a year. All this in the midst of a pandemic that has caused the worst global downturn since the Great Depression.

Certainly, Canada’s federal government led by the Trudeau liberals has followed international advice to introduce unprecedented income security programs like the Canadian Emergency Response Benefit and Canadian Emergency Wage Subsidies. And these emergency response measures have helped millions of the unemployed from going broke.

But as a highly decentralized federal country, provincial Conservative governments across the country have followed their well-worn routines of doing as little as possible and seeking cuts where and when they can. Most notably, when offered billions in emergency federal dollars on health, long-term care and housing in the past year, most provincial administrations have simply sat on the cash, even as hospitals and public health agencies struggled and COVID-19 infection rates skyrocketed in recent months.

Canada’s provincial governments – like their American counterparts – have also continued to turn a blind eye to mounting social problems. In Alberta, rather than invest, the Jason Kenney’s Conservative government has made deep provincial cuts to the provincial budget, forcing the University of Alberta to lay off 400 people, with another 650 to be let go in the coming year.

In Ontario, the Conservative Ford government has similarly sat back and watched Ontario’s public institutions struggle. In long-term care, a lack of funding and oversight has led to thousands dying.

While in Ontario’s universities, Ford has cut hundreds of millions of dollars from post-secondary education and threatens to cut even more with its planned “performance” based funding plan for universities and colleges. All this in follow up to the long-term provincial trend where public funding for Ontario’s universities and colleges ranks last in public per-student funding in Canada.

It is these unsustainable funding arrangements that have piled even greater financial pressure onto already stretched undergraduate universities like Laurentian. But many more universities across Canada – like Concordia, St. Thomas, and Nipissing – are on the ‘watch’ list with unsustainable debt from years of trying to cope with declining public support and provincial governments trying to force universities and colleges to be operated like corporations.

But apparently the Ford government is ready to go the next step and allow Ontario universities to fall into such a state of crisis that they have to declare insolvency – a “shock” that will allow these institutions to unilaterally cut programs, lay off faculty and staff, and gut collective agreements. Of course, during this process financial firms like Ernst and Young as well as major corporate law firms will reap tens of millions from public coffers all in order to “oversee” Laurentian’s “restructuring.”

But this is unprecedented. Never before has any university or public sector institution been allowed to go into insolvency. Never before has government tried creditor protection as a solution to cutting public services to Canadians. But this is neither justifiable. Nor is it anything like a reasonable long-term solution for Laurentian, students, or any of Canada’s universities or public sector institutions.

Inoculating Against the ‘Inequality Virus’

Instead, different choices are needed to improve our post-secondary education system. For a start, additional federal funds are needed immediately to ensure that no other university falls into insolvency. Provincial funds should also be invested into all universities that are struggling with the sudden decline of enrolment or lack of international students.

And in the long-term, the federal government needs to step up and put in place an actual plan for the long-term public funding of post-secondary education in Canada – a plan that includes doing away with tuition fees as is common in more than eleven countries in Europe and where more than 90 percent of all post-secondary revenues are provided by government.

The International Monetary Fund and the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development – neither of which have traditionally been the most progressive institutions – have both recently stated that clear, strong, and progressive public policies are required to address the pandemic and the global downturn.

So too as Oxfam has argued, if the ‘Inequality Virus’ is to be dealt with, then government action is needed to protect people’s health and their public services. In their view, there should be no return to austerity – and by implication – no return to ‘shock doctrine’ type policies if countries are to recover economically or address the climate crisis.

Canadian officials should be paying attention. No public university or other public institution in Canada should have to claim it is broke. Nor should any government stand idly by while the wealthy reap enormous dividends, students are saddled with debt, and communities faced with the possible closure of their local campuses.

There should be no return to inequality as usual. But if we are to avoid another dose of “shock therapy,” then we will have to reflect seriously on what really matters, and what we most value.

A good place to start is thinking about what it means for the first public university in Canada to ever file for creditor protection, and why more than ever we need a robust public post-secondary system that creates a more equal and sustainable world. If we don’t? We can expect to see the same crisis unfolding at Australian and American universities and colleges – and now at Laurentian – to be repeated again and again in the coming months and years. ‘Shocks’ that no one needs to see. •